2023 Fourth Annual Report of the Disability Advisory Committee

Table of Contents

- Committee Members

- Authors

- Acknowledgements

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction and Background

- 2. Disability Advisory Committee Discussions and Recommendations (2022 to 2023)

- 3. Conclusion

- References

- Appendix A: The Disability Tax Credit Explained

- Appendix B: The Disability Advisory Committee Terms of Reference

- Appendix C: Report card

- Appendix D: The ASE Community Foundation for Black Communities with Disabilities DAC Data feedback

- Appendix E: Overview of non-participation in the DTC in Quebec, reflections and recommendations

- Appendix F: Additional information on data

- Appendix G: Committee Members

- Appendix H: Federal Measures for Persons with Disabilities

- Appendix I: Disability Measures Linked to Disability Tax Credit Eligibility

- Appendix J: Form T2201, Disability Tax Credit Certificate

- Appendix K: Resources on Language and Disability

- Appendix L: Factsheet – Indigenous Peoples

- Appendix M: Updated Tables for the DTC Statistical Publication - PDF versions

Committee Members

The Disability Advisory Committee is made up of 12 members including two co-chairs. The Committee includes professionals from various fields, such as health professionals, lawyers, accountants, and tax professionals, as well as advocates for the disability community, representatives of Indigenous communities, and persons with disabilities.

The Committee is composed of voluntary members, including persons with disabilities, health providers and professionals from a variety of fields, such as tax professionals and lawyers. The Committee is currently co-chaired by Sharon McCarry, Founder and Executive Director, La Fondation Place Coco, and by Gillian Pranke, Assistant Commissioner, Assessment, Benefit, and Service Branch, Canada Revenue Agency (CRA). Jonathan Lai serves as vice-chair. The complete membership of the committee can be found in Appendix B.

Authors

Prepared for the Disability Advisory Committee by members of the Disability Policy Research Program: Brittany Finlay, Christiane Roth, Stephanie Chipeur, Ken Fyie and Jennifer Zwicker

Acknowledgements

The Committee acknowledges the following individuals who participated in its consultations to inform the development of this report: Laura Fregeau, Liam Bienstock, Parth Shah, and Chelsea Bell Eady.

Executive Summary

The Disability Advisory Committee (DAC) advises the Minister of National Revenue and the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) on how the Agency can improve the way it administers and interprets tax measures for Canadians with disabilities. This report delivered by the DAC explores the challenges and opportunities surrounding the disability tax credit (DTC) in Canada, a crucial federal tax credit that assists individuals with disabilities and their supporting family members. The report begins by underlining the significance of this issue, highlighting that one in five Canadians aged 15 and older, approximately 6.2 million people, have a disability according to the 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability. Demographic information highlights the diverse needs of the population that must be considered.

The DAC highlights the important need for more data to help inform design and implementation of the DTC program and the need to shift from the medical model to the biopsychosocial model of disability, emphasizing the importance of considering biological, psychological, and social factors when understanding an individual's medical condition. This shift aligns with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and underscores the need to remove societal barriers to enable full participation for people with disabilities.

This report describes the DTC and its critical role in supporting individuals with severe disabilities in mitigating additional costs that act as barriers to participation in society. The multi-step process to obtain the DTC is detailed, with a focus on identifying potential barriers at each stage.

The DAC has produced several recommendations to address issues with the process to access the DTC. The report presents 26 recommendations aimed at enhancing the DTC program and addressing issues of eligibility, accessibility, and outreach. These recommendations cover a wide range of areas, from reframing the definition of disability to tracking user feedback for the online DTC application, improving public education, making the DTC refundable, and enhancing healthcare provider support. The 26 recommendations are described, in alignment with the process for applying for and accessing the DTC.

Recommendation 1: Reframe the definition of disability in the Income Tax Act to shift towards a biopsychosocial model of disability through consultations with persons with disabilities and clinical practitioners.

Recommendation 2: Modify questions in the DTC client experience survey by way of a co-design approach with persons with disabilities to increase awareness, accessibility, and uptake of the survey.

Recommendation 3: Design and launch a survey to measure health practitioner experience with the DTC application process.

Recommendation 4: Track and integrate user feedback for the new online DTC application.

Recommendation 5: Use existing data sources from Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), Statistics Canada, and the CRA to analyze the population that:

- obtains the DTC,

- the population that does not obtain the DTC certificate but is potentially eligible,

- and the population that obtains other DTC-dependent services.

Recommendation 6: The CRA, with consultations led by Black, Indigenous, and other communities of persons with disabilities, develop mechanisms for collecting data related for example to race, ethnicity, immigrant status, age, gender identity, and type of disability, while respecting and protecting the confidentiality of the individual and community. Any new DTC application form should include an option for applicants to identify by the demographic categories stated here. As outlined in the Income Tax Act, data should be used to monitor, to do outreach to marginalized and underserved communities, and for statistical purposes.

Recommendation 7: Set targets (and review these targets at regular intervals) to increase DTC applications by Black, Indigenous Peoples, and other racialized persons through consultations with individuals with lived experience from these communities. Targets should align with population estimates from the Canadian Survey on Disability.

Recommendation 8: Develop a pilot project as described above in partnership with navigators from trusted community organizations to simplify the DTC application process for Indigenous communities. This project should involve discussions with nation, Métis and Inuit health authorities and be co-designed alongside each group. Data with respect to uptake rates should be collected to measure and evaluate success of the pilot in accordance with guidelines from the First Nations Information Governance Centre, Statistics Canada, and the principles of ownership, control, access, and possession (OCAP).

Recommendation 9: Systematically identify and address the identified barriers facing DTC applicants in Quebec and the territories to measurably increase uptake of the DTC.

Recommendation 10: In partnership with the Department of Finance Canada and ESDC, set targets for reducing discrepancies in participation in the DTC for Quebec and the territories. The action plan should be reviewed at regular intervals, and targets should align with population estimates from the Canadian Survey on Disability.

Recommendation 11: Study the points of convergence between the eligibility criteria for provincial/territorial programs and the DTC to recognize equivalencies and, ultimately, adopt a standard from Accessibility Standards Canada. This could entail granting recipients of disability benefits from other levels of government automatic eligibility for the DTC.

Recommendation 12: Make sure future changes to the design and implementation of programs, including associated application processes and appeal processes, are co-designed with individuals with expertise, including those with lived experience and relevant practitioners. We recommend that the co-design process be thoughtfully designed in consideration of the practices outlined in this report and in consultation with experts in co-design.

Recommendation 13: Make sure all of the CRA’s communications and publicly available information adheres to universal design, in consultation with people with disabilities.

Recommendation 14: Design and implement strategies to improve public education about the DTC, with an emphasis on its role as a gateway to disability programs and supports.

Recommendation 15: Systematically identify and address barriers to DTC applications by persons with disabilities, caregivers, and healthcare providers.

Recommendation 16: Make the DTC a refundable tax credit to increase DTC applications, particularly among individuals at lower income levels.

Recommendation 17: Remove the 90% criteria from the DTC application and provide a framework for healthcare providers and CRA staff to apply the “all or substantially all of the time” criteria to episodic conditions.

Recommendation 18: Remove questions about caregiving requirements in the mental functioning impairment section of the DTC application.

Recommendation 19: Improve resources, knowledge, and training to support healthcare providers in filling out DTC certificate applications.

Recommendation 20: Expand the range of professionals who can fill out the DTC certificate applications to any licensed health or social services provider.

Recommendation 21: Increase the number of CRA navigators, and highlight and enhance the navigator role, to improve transparency and reduce barriers to applying for the DTC. This could include outsourcing parts of the navigator role to external organizations with existing expertise and capacity.

Recommendation 22: Develop a distinct accessible support pathway for the newly launched, fully digital application.

Recommendation 23: Provide guidelines for practitioners regarding fees for completing the DTC certificate application.

Recommendation 24: Provide public data on the number of, and reasons for, reviews of, and objections to, DTC rulings by the CRA.

Recommendation 25: Coordinate a multi-ministry committee (consisting of representatives from the CRA, ESDC and the Department of Finance Canada) to review registered disability savings plan legislation.

Recommendation 26: Provide an official DTC certificate document to DTC recipients.

One significant issue highlighted is that there is a gap in data capture and analysis when persons with disabilities do not apply for the DTC for various reasons. An exploratory analysis using linked data from the 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability and CRA tax data reveals that only a fraction of those eligible for the DTC successfully complete the application process, mainly due to challenges starting the application and filing an income tax and benefit return.

The DAC acknowledges the need for co-operation among government agencies and departments, at the federal, provincial, and territorial levels, to effectively improve tax measures and support services for individuals with disabilities. The report underscores the importance of co-designing policies and services with underserved groups and those with expertise in this area. This report highlights the pressing need to address the challenges faced by Canadians with disabilities in accessing the DTC and related services. The recommendations put forth seek to promote inclusivity, equity, and improved quality of life for individuals living with disabilities in Canada.

1. Introduction and Background

1.1. Disability in Canada

Persons with disabilities represent a diverse portion of the Canadian population with one in five people in Canada aged 15 years and older (an estimated 6.2 million people) having a disability (2017 Canadian Survey on Disability). There are several key demographic patterns among Canadians with disabilities, including:

- the prevalence of disability increases with age, from 13% among youth aged 15 to 24 years, to 20% among working age adults aged 25 to 64, and to 47% among persons aged 75 years and over

- of the 6.2 million Canadians aged 15 years and over with a disability, 37% were classified as having a mild disability; 20%, a moderate disability; 21%, a severe disability; and 22%, a very severe disability

- women have higher rates of disability than men. The prevalence of disability is 24% for women, versus 20% for men for those aged 15 years and over

- almost one in three Indigenous people have a disability, a much higher rate than that of the general population

Today, most academic and policy discussions about disability address the importance and desire to shift from the medical to the biopsychosocial model of disability. The medical model, which characterizes illness and loss of function for persons with disability in categorical or diagnostic terms, is still predominant in health and social systems in Canada. While this framing may be helpful for clinical settings, the disability community largely rejects the medical model in favor of the biopsychosocial model. The biopsychosocial model, first conceptualized by George Engel in 1977, suggests that there are multiple factors to consider when understanding an individual’s medical condition:

- biological factors, which encapsulate the physiological pathology of a certain condition

- psychological factors, which encapsulate the emotions and behaviors associated with a certain condition

- social factors, which encapsulate socioeconomic and cultural factors experienced by the individual, such as family circumstances and socioeconomic status, among others

The biopsychosocial model aligns with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and focuses on addressing barriers that may prevent or limit one’s full participation in society. This model also promotes the idea that adapting social and physical environments to accommodate people with a range of functional abilities improves quality of life and opportunity for people with and without impairments.

This report provides information on the DTC and the process to access it. Population data is presented to provide context on usage of the DTC among persons with disabilities in Canada. The report then details 26 recommendations from the Committee, highlighting the issues at hand, progress to date and next steps. A report card describes these recommendations within the context of progress on past Committee reports.

1.2. The Disability Tax Credit Explained

Introduction

The DTC is a non-refundable federal tax credit that helps people with disabilities, or their supporting family member, reduce the amount of income tax they may have to pay. To be eligible for the DTC, applicants must have a severe or prolonged impairment in physical/or mental function impeding their ability to conduct activities of daily living.

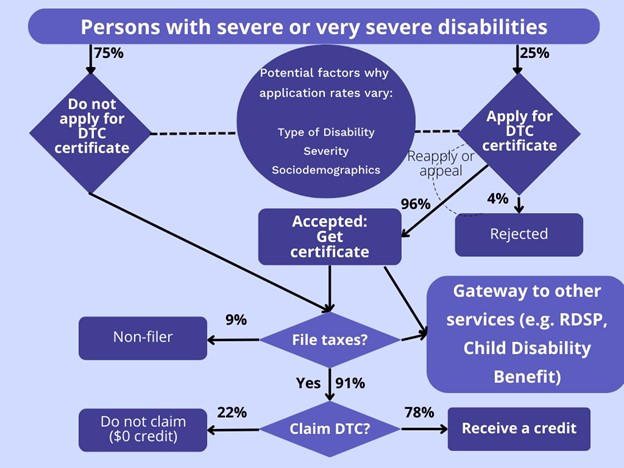

The primary support offered through the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) to persons with disabilities is the DTC. The DTC is designed as a horizontal tax equity instrument to provide tax relief for the additional costs that persons with severe disabilities may face as barriers to participation in society (Canada, 2017; Disability Advisory Committee, 2019; Dunn & Zwicker, 2018). The process to receive the DTC involves multiple steps, as depicted in Figure 1 and explained in detail in Appendix A. From being aware that the DTC exists, through applying for and receiving the DTC certificate, to finally receiving the DTC and potentially benefits from other programs, each step presents a potential barrier to applicants. These steps, and recommendations to improve the steps, are among those presented later in this report.

Figure 1: Roadmap for persons with disabilities to receive the DTC

The CRA has provided public numbers that detail who is receiving the DTC and some demographic information (province, age, gender, duration, marital status) on those who receive a DTC certificate. However, there are disabled individuals who do not apply for the DTC certificate for various reasons. This population is not captured in the CRA data and has not been detailed thoroughly in previous reports.

Using data linking survey responses from the 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability (CSD) with CRA tax data, an exploratory analysis describes who is and who is not applying for the DTC certificate, and who is claiming the DTC (details on data in Appendix F). Following the roadmap, this analysis shows one barrier is beginning a DTC application. In 2017, only 25% of those identified as having a severe or very severe disability in the CSD applied for a DTC certificate. Another barrier arises with filing an income tax and benefit return: For those who did apply, only 91% filed a return in 2017. Filing a return is critical to receiving the DTC.

The CRA accepted, either at first or through subsequent attempts, most applications: 96% for those either severely or very severely disabled were eventually accepted. Of those that are accepted though, only 78% received the DTC for themselves. Some individuals may transfer their credit to spouses or other supporting family members.

When all severity levels are combined, only 11% of persons with disabilities completed the roadmap: applied for the DTC certificate, received the DTC certificate, filed a return, and subsequently claimed the DTC for themselves. Focused on those most severely disabled, the proportion receiving a certificate and claiming the DTC for themselves is 25%. These results are summarized in Table 1 below.

| Population: 2017 CSD disabled | Total persons with disabilities | Severity level of the persons with disabilities population | Severity level of the persons with disabilities population | Severity level of the persons with disabilities population | Severity level of the persons with disabilities population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Very Severe |

| % filing a tax return in 2017 | 93% | 94% | 94% | 92% | 89% |

| % applying for a DTC certificate in 2017 | 14% | 5% | 10% | 16% | 33% |

| % rejected for a DTC certificate | 5% | 5% | 7% | 6% | 4% |

| % of persons with disabilities receiving DTC in 2017 | 11% | 3% | 7% | 11% | 25% |

| % of those with a DTC certificate receiving the DTC in 2017 | 77% | 66% | 80% | 77% | 79% |

The low application rates, as well as issues surrounding rejections and not receiving the DTC as a tax credit, will be explored in the subsequent section of this report.

2. Disability Advisory Committee Discussions and Recommendations (2022 to 2023)

The Committee provides advice to the minister of national revenue and the CRA on improving the administration and interpretation of tax measures for Canadians living with disabilities. A detailed description of the Committee’s mandate and membership is provided in Appendix B. Since its establishment in November 2017, the DAC has produced four reports. A report card on the achievements and progress of previous recommendations is provided in Appendix C.

This fourth report summarizes the DAC’s work, the progress of previous recommendations, and provides 26 additional recommendations. Recommendations are categorized based on the following:

- core and cross-cutting themes, including the definition of disability, data, populations of special consideration, regional considerations, co-design and accessibility

- issues related to accessing the DTC, including awareness, eligibility, application, appeals and gateway to other benefits

2.1. Discussions and Recommendations in Relation to Core, Cross-Cutting Themes

2.1.1. Definition and Approach to Disability

Current Issue

The current definition and approach to disability (as outlined in the Income Tax Act) used by the federal government to determine eligibility for the DTC and other disability benefits lacks inclusivity. There is a need to consider the biopsychosocial aspects of disability when determining who is eligible for disability benefits.

Progress to Date

In the 2022 report, the DAC noted that the DTC itself illustrates the conflict of the social and medical models of disability. Eligibility criteria are based on function, all or substantially all of the time. Applicants and their close contacts have a first-hand understanding of their function all or substantially all of the time, but DTC applications still rely on the judgment of a health provider. The DAC has pointed out that health providers are not with the applicants all or substantially all of the time. Steps have been taken to encourage medical practitioners to consult with their patients and provide information shared by their patient. The clarification letters advise medical practitioners to consult with their patients in order to answer the questions posed. This practice is also reinforced by medical advisors when speaking to medical practitioners. These are promising steps but there remains a need for more progress on this issue.

Next Steps and Recommendations

In their discussions over the past year, the DAC has highlighted the importance of integrating aspects of societal participation into the definition of disability in recognition of the broad scope of support that persons with disabilities require on a daily basis. This includes considering the applicant’s capacity to engage in essential acts of daily living, such as dressing, self-care, and medication management, among others.

Committee members and professionals consulted as part of the DAC’s work advocate for a shift towards a biopsychosocial model of disability. The DAC advocates for this shift, as it aligns with the commitments of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and allows for a more holistic view of disability beyond a medical diagnosis, while continuing to retain biological aspects of disability that are not purely social in nature.

Recommendation 1: Reframe the definition of disability in the Income Tax Act to shift towards a biopsychosocial model of disability through consultations with persons with disabilities and clinical practitioners.

2.1.2. Data

Client Experience Survey

Current Issue

There is little information on whether clients (people with disabilities, their families or caregivers, or others who are assisting in completing DTC applications) are satisfied with, and getting the necessary information to successfully complete, the application process. A DTC client experience survey exists, but it has only a small number of responses relative to the number of DTC applicants and recipients, dramatically affecting the reliability and usability of the data.

Progress to Date

Based on a DAC recommendation in 2019, the CRA developed the client experience survey. Subsequent recommendations have been made in previous DAC reports to improve questions in the survey, to improve completion rates, and to make the survey more accessible. For example, the Committee asked the CRA to include a question in the survey about access to health providers in response to applicant concerns. The DAC wanted to know more about the access problems that DTC recipients face. The CRA modified the questions in the survey, based on input from Committee members. As of June 2023, the following additional changes are being implemented by the CRA to improve the survey:

- to improve the survey’s content, a careful analysis of each question, and the type of data it will yield, is underway

- to reduce the overall number of survey questions, the CRA is in the process of building a more dynamic and accessible survey, where the questions adapt to the answers provided

- a new introduction to the survey is being developed to encourage survey completion. The addition of a survey progress bar is also being investigated

- a review of the language level used and e-reader capabilities is being completed to make sure the survey meets the accessibility standards for persons with disabilities

- options to make the survey more readily available, such as through a direct online link, are being explored

- a review of various promotional strategies to raise awareness, to encourage participation and to remind applicants about the survey is in progress. Using existing tools such as CRA navigators and social media is likely. However, new promotional tactics are being explored as well

Next Steps and Recommendations

The DAC commends recognition of the need to make substantial progress on the client experience survey. One of the primary concerns of the DAC moving forward is the consistent, relatively low uptake and completion rate of the survey among those applying for the DTC. The length of the survey and its non-inclusive language are two areas that have been highlighted and have been noted by the CRA as areas where improvements are underway. The survey has the potential to provide valuable information from the perspective of applicants, which can ultimately improve the DTC application process. As such, increasing uptake and completion of the survey is an important priority moving forward. Considering the recent launch of the digital DTC application, the survey could be an important means to gather information about the user experience with this new process. The DAC suggests the CRA consider the following:

- include the link to the survey on My Account or have the survey embedded in digital tax forms

- promote the survey to those who have not completed a DTC application but may be eligible, including on web pages on Canada.ca

- consult persons with lived experience to determine ways to make the survey more accessible

While it is important to capture perspectives from the individuals applying for and receiving the DTC, the DAC recommends expanding the survey to include perspectives from practitioners that fill out portions of the DTC application. This would allow the CRA to learn more about the process of applying for the DTC from multiple perspectives to improve the application process for all users.

Recommendation 2: Modify questions in the DTC client experience survey by way of a co-design approach with persons with disabilities to increase awareness, accessibility, and uptake of the survey.

Recommendation 3: Design and launch a survey to measure health practitioner experience with the DTC application process.

Recommendation 4: Track and integrate user feedback for the new online DTC application.

Data Strategy

Current Issue

Information regarding DTC application processes is minimal, such as the percentage of those with a disability applying, the sociodemographic characteristics of those who apply, and what characteristics in the application or among applicants are associated with rejections.

Progress to Date

From 2011 to 2021, the CRA published DTC statistics with an increased amount of data based on DAC recommendations and requests. These statistics include the number of individuals with an accepted certificate and sociodemographic characteristics of these individuals, as well as the number of individual applications that are accepted or rejected. Applicant satisfaction data with the process has been collected through the client experience surveys as noted above in an effort to get further characteristics of applicants with accepted or rejected applications.

The DAC has previously requested that the CRA provide and make publicly available relevant data on the DTC, including number of applications, approvals, rejections, and appeals; durations of eligibility by function; and a demographic profile of current beneficiaries by age and gender. These data are, in part, available on the CRA webpage detailing Disability Tax Credit statistics.

The DAC has also made the following data requests:

- Percent of applicants relative to those eligible – Sociodemographic information such as age, gender, region and ethnicity, describing how effectively the DTC is reaching those it is designed to support

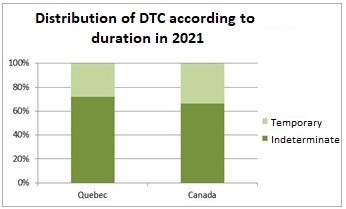

- Temporary/Permanent status – There is generally a higher rate of temporary DTC approvals for the Atlantic region. However, the DAC was unable to ascertain from the numbers whether this imbalance was the result of the functions for which applicants were claiming

- Reapplications – There are a large number of middle-age applicants who are expected to reapply for the DTC. More information on these cases is required

- Potential recipients – What proportion of the caseload applies for the DTC only to help offset their costs; what proportion applies only to gain access to other disability-related benefits; what proportion does both. It is important to have some indication of the number of claimants benefiting from a tax reduction, compared to the number of claimants who do not benefit from a tax reduction

The CRA has not provided this information, but it continues to discuss these requests with relevant teams. In some cases, the CRA takes the position that it cannot gather this information from its current data.

Next Steps and Recommendations

Current data summaries prepared by the CRA have led to insights about DTC recipients and potential areas for improvements to the DTC process. To further improve the process – For instance, to determine whether specific communities or populations are seeing worse rates of DTC certificate acceptances, or higher rates of DTC utilization, further data summaries should be prepared where data is available and collected by the CRA.

The DAC has also consistently recommended that the CRA (in partnership with the Department of Finance Canada, Statistics Canada, and the disability community) undertake a study of the current data needs regarding the DTC and identify appropriate new ways of tracking necessary DTC information, including the estimated number of Canadians who potentially would be eligible for the DTC but cannot benefit because of its non-refundable status. No such study has been initiated by the CRA.

As the DTC is the gateway to other disability supports provided by other ministries, data and findings from the CRA can and should be incorporated into cross-ministerial analyses. To date, these sources are siloed from each other, and a holistic view of accessibility to governmental supports for disability cannot be provided. To start, a data strategy detailing what is available, and what can be analyzed from all ministries, including the CRA, should be developed. Missing data can be noted and linking strategies can then be developed to aggregate the information. Tracking this information will allow the CRA to highlight service accessibility, as well as to note how and with whom the DTC and related benefits are not being utilized.

Recommendation 5: Use existing data sources from Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), Statistics Canada, and the CRA to analyze the population that:

- obtains the DTC,

- the population that does not obtain the DTC certificate but is potentially eligible,

- and the population that obtains other DTC-dependent services.

Populations of Special Consideration

Current Issue

Indigenous Peoples, Black Canadians, and other racialized groups with disabilities are more likely to experience barriers to accessing disability services and supports to which they are entitled.

Progress to Date

In previous reports, the DAC has focused on the barriers experienced by Indigenous Peoples with disabilities but has not addressed barriers experienced by Black and other racialized people with disabilities.

In response to DAC recommendations about issues specific to Indigenous Peoples, the CRA has taken the following actions:

- increased its investment in its Community Volunteer Income Tax Program, particularly among organizations serving Indigenous Peoples

- hired Indigenous staff and provided CRA staff with Indigenous cultural sensitivity training, though specific numbers have not been provided

- reorganized its operations by creating the Disability, Indigenous, and Benefits Outreach Services Directorate

- plans to hire Indigenous navigators to complement the services provided by the CRA navigators who assist DTC applicants with complex cases. Of note, the CRA has yet to report on whether this has occurred

- working with Indigenous Services Canada and the Indigenous Services Branch at ESDC on a tool to encourage Indigenous Peoples to file an income tax and benefit return, though the CRA has yet to report on whether this has occurred

The DAC has not received a response from the CRA about its recommendations for the following:

- that the CRA develop an internal educational program to promote a better understanding of Indigenous systems in Canada and how the CRA and the DTC interact with people with disabilities, their families and their caregivers

- that the CRA develop an assessment package, similar to the one used for the Canada Pension Plan disability benefits application, which speaks to Indigenous Peoples

- that the CRA make sure that individuals responsible for Indigenous children and youth are informed that the costs of completing a DTC application are covered under Jordan’s Principle

Next Steps and Recommendations

A submission to the DAC (Appendix D) highlighted that Black Canadians with disabilities experience higher rates of poverty than any other racial or ethnic group in Canada. This is made even more difficult by the fact that Black Canadians with disabilities are more likely to experience barriers to accessing supports and often face discrimination when accessing services. At present, it is challenging to identify and address the specific barriers that Black Canadians face during the process of accessing government supports due to a lack of data disaggregated by race and ethnicity. Without this data, it is difficult to identify the specific barriers experienced by Black Canadians with disabilities and develop targeted and coordinated approaches to address the barriers.

Further, the DAC reviewed a report from Indigenous Disability Canada / the BC Aboriginal Network on Disability Society, which provided 30 recommendations over five categories relating to increasing access and reducing barriers to the DTC among Indigenous Peoples in Canada (which includes First Nations, Inuit and Métis). This report highlights the need to break down historical barriers that have contributed to a deep mistrust in the Canadian federal system, which has led to a low uptake of the DTC and associated federal disability programs among Indigenous Peoples. As such, this report proposes the development of a pilot project that would simplify the tax-filing process for Indigenous Peoples. This project has two primary objectives:

- allow Indigenous tax-filers to submit a simplified income tax and benefit form with a trusted community advocate or navigator. This form would allow the tax-filers to identify themselves as a person with a disability, signaling the need to begin the process to submit a T2201

- allow Indigenous applicants to submit a simplified T2201 form with a trusted community advocate or navigator who can verify their disability to a CRA navigator. This would allow Indigenous applicants to get access to the benefits to which they are entitled, while ensuring they go through the process of applying alongside a person they can trust

The DAC fully supports the creation of such a pilot project to increase uptake of the DTC among Indigenous Peoples.

Recommendation 6: The CRA, with consultations led by Black, Indigenous, and other communities of persons with disabilities, develop mechanisms for collecting data related for example to race, ethnicity, immigrant status, age, gender identity, and type of disability, while respecting and protecting the confidentiality of the individual and community. Any new DTC application form should include an option for applicants to identify by the demographic categories stated here. As outlined in the Income Tax Act, data should be used to monitor, to do outreach to marginalized and underserved communities, and for statistical purposes.

Recommendation 7: Set targets (and review these targets at regular intervals) to increase DTC applications by Black, Indigenous Peoples, and other racialized persons through consultations with individuals with lived experience from these communities. Targets should align with population estimates from the Canadian Survey on Disability.

Recommendation 8: Develop a pilot project as described above in partnership with navigators from trusted community organizations to simplify the DTC application process for Indigenous communities. This project should involve discussions with nation, Métis and Inuit health authorities and be co-designed alongside each group. Data with respect to uptake rates should be collected to measure and evaluate success of the pilot in accordance with guidelines from the First Nations Information Governance Centre, Statistics Canada, and the principles of ownership, control, access, and possession (OCAP).

Regional Considerations

Current Issue

The uptake of the DTC in Quebec and the territories is much lower relative to the rest of Canada. In Quebec this is particularly evident in older adults and seniors (age 45 years and older). Because of the relatively higher incidence of disability in the Indigenous population, it would be reasonable to assume that there would be more DTC uptake from the North.

Progress to Date

In previous reports, the DAC recommended that the CRA collaborate with the Province of Quebec to determine a single eligibility process for the provincial and federal tax credits available for Quebecers with disabilities. The CRA has yet to respond, other than to indicate some discussions are being held with Revenu Québec. The Service, Innovation and Integration Branch of the CRA has also indicated that they are in the process of analyzing a report on DTC uptake in Quebec, which we detail in the following section.

Over the years, the DAC has consistently expressed concern about the relatively low uptake of the DTC in Quebec. ESDC has funded a Quebec-based study to determine why this is the case. A study has been completed and the DAC awaits updates on actions to be taken from the study.

In 2019, the CRA opened three northern service centres in Yellowknife, Iqaluit and Whitehorse in order to improve services in the territories. Staff who field phone calls from area codes in the North have received cultural training.

The DAC has noted that there is limited access to qualified health providers in northern and remote communities and there are high travelling costs. The DAC has raised the question of whether designated individuals who are widely recognized in the community, such as early childhood educators, teachers and local healers, could be included as qualified health practitioners for the purposes of completing the DTC application. The CRA has not responded to this issue other than to modify the questions in the client experience survey to collect responses about expanding the list of qualified health providers.

Next Steps and Recommendations

A submission to the DAC (Appendix E) noted that the proportion of individuals accessing the DTC that lived in Quebec was less than the proportion of the total Canadian population living in Quebec across age groups and impairment. Complementary to this submission, exploratory analysis from the University of Calgary showed that in 2017, 7% of the population with a disability according to the CSD in Quebec received the DTC. This compares to 9 to 19% in other regions. Of note, the Northern Territories (Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut combined) have a rate of 5%. This is highlighted in the provincial/territorial rates of DTC uptake depicted below (Figure 2).

Figure 2: DTC Uptake Rates in 2017

The submission highlighted three main barriers to accessing the DTC in Quebec:

- people in Quebec struggle to label themselves or their children as disabled. While it is unclear exactly why this is the case, one hypothesis is that the French term handicapé may seem harsher that its English equivalent disabled

- people in Quebec experience difficulties accessing health professionals. In Quebec, there has been an increasing widespread difficulty accessing a family physician. Additionally, there seems to be reluctance among some health professionals to fill out forms on behalf of their patients

- there is widespread belief in Quebec that, for people who do not pay taxes, the DTC provides no benefit or that accessing the DTC may reduce the amount of social solidarity benefits they receive

Moreover, the DAC discussed that there are large variations in eligibility criteria between federal, provincial, and territorial disability programs. This creates additional barriers for applicants seeking support from multiple different disability programs. In Quebec, for example, the two-remittance tax system results in a lack of communication between federal and provincial tax benefit administrations. While in theory the T2201 form can be used as a replacement for the Quebec version of the form (TP-752.0.14-V, Certificate Respecting an Impairment) when applying for provincial tax credits, in practice, many applicants are asked to fill out the TP-752.0.14-V, despite having a completed T2201 form. This creates an unnecessary burden on both applicants and providers. This leads to an emphasis on ensuring cross-provincial fairness in accessing and completing the requirements for obtaining the DTC.

Harmonizing eligibility criteria across levels of government through the creation of a framework of standards is an important step that would allow for fairer and more predictable access to programs for persons with disabilities and their families. Further, the creation of this framework would meet one of the objectives of Accessibility Standards Canada, which is to promote access to programs.

To promote equity across Canada and ensure all Canadians with disabilities are accessing the benefits to which they are entitled, it is essential for the Government of Canada to address these concerns.

Recommendation 9: Systematically identify and address the identified barriers facing DTC applicants in Quebec and the territories to measurably increase uptake of the DTC.

Recommendation 10: In partnership with the Department of Finance Canada and ESDC, set targets for reducing discrepancies in participation in the DTC for Quebec and the territories. The action plan should be reviewed at regular intervals, and targets should align with population estimates from the Canadian Survey on Disability.

Recommendation 11: Study the points of convergence between the eligibility criteria for provincial/territorial programs and the DTC to recognize equivalencies and, ultimately, adopt a standard from Accessibility Standards Canada. This could entail granting recipients of disability benefits from other levels of government automatic eligibility for the DTC.

Co-Design and Accessibility

Current Issue

Many of the disability programs currently administered by the federal government have issues relating to low uptake, awareness, and accessibility. As required by the Accessible Canada Act, the CRA and other federal government agencies and departments must publish annual accessibility progress reports that outline efforts to deliver on accessibility plans (which for the CRA, includes the DTC). It is not clear how these plans will be used, and there are concerns that the plans typically do not have inclusive co-design approaches and methods in development and implementation.

Progress to Date

In the past, the DAC created an Indigenous Issues Task Group, which, among its recommendations, emphasized the need to ensure that representatives of Indigenous Peoples are actively engaged in the co-design, implementation and delivery of programs and services intended for their benefit. The CRA noted that efforts are underway throughout the federal government to engage more Indigenous Peoples in this process and move toward the Indigenization of many of its procedures. The DAC has yet to obtain a response about how specifically such co-design would take place.

Previous discussions further focused on the accessibility of the CRA’s communications, with recommendations to hire a student from the Ontario College of Art and Design University’s Inclusive Design master’s program to review sample communications. The DAC has asked the CRA about whether its website, publications, communications and forms have undergone an accessibility audit. All CRA forms should clearly state that they will be provided in alternate format on request. The DAC also recommended that the CRA provide training on person-first language for its public-facing staff. The CRA has not reported on any accessibility audits so far. However, the Accessibility Assessment ToolKit initiative and accessibility framework is being implemented with the goal to track and report on the Agency's progress with respect to compliance with the accessibility standards introduced through recent changes to Canada's accessibility legislation. Progress in improving accessibility of internal and external communications is anticipated, based on CRA’s Accessibility Plan.

Next Steps and Recommendations

To improve low uptake, awareness, and accessibility of the DTC, the DAC recommends the CRA adopt a co-design approach in all its work. The DAC consulted with Inclusive Design students at the Ontario College of Art and Design University to learn about best practices for an effective and thoughtful co-design process that could be implemented by Government of Canada organizations moving forward. A summary of these practices is outlined below:

- The co-design process differs from a consultation in that it requires the thoughts and opinions of co-designers to be centered throughout the entirety of the design process. This requires consistent and ongoing communication, as well as frequent engagement throughout the process

- Make sure that there is diversity among individuals that are part of the co-design process to ensure that co-designers are as representative as possible of the general population. Many characteristics, such as location of residence, income level, race, ethnicity, age, and gender, are important to consider in developing a diverse group of co-designers. In line with this, the co-design process must be culturally safe to ensure all participants feel comfortable participating

- Power imbalances between co-designers and government representatives need to be decreased to the greatest extent possible

- Consider multiple different ways of engaging co-designers to ensure as many people can be included as possible and to ensure that the process is accessible to everyone (for example, using in-person and virtual meetings, and finding ways to engage with individuals that have challenges with verbal communication)

- Make sure that co-designers are adequately compensated in a way that does not interfere with their access to other benefits or their taxable income

- Sufficient training of those planning to facilitate the co-design process is required to ensure that facilitators can hold space for issues that are often emotional for many and not perpetuate further harm against a community. This is key to establishing trust between facilitators and co-designers

- Be open to changing the way things are typically or have previously been done to create a more accessible process

Recommendation 12: Make sure future changes to the design and implementation of programs, including associated application processes and appeal processes, are co-designed with individuals with expertise, including those with lived experience and relevant practitioners. We recommend that the co-design process be thoughtfully designed in consideration of the practices outlined in this report and in consultation with experts in co-design.

Recommendation 13: Make sure all of the CRA’s communications and publicly available information adheres to universal design, in consultation with people with disabilities.

2.2. Discussions and Recommendations in relation to the DTC Access Roadmap

2.2.1. Awareness

Current Issue

There is a widespread lack of awareness about the DTC across Canada among eligible populations.

Progress to Date

From its inception, the DAC has taken a strong position that the DTC ought to be transformed from a non-refundable credit into a refundable credit to be fair to low-income Canadians and improve their uptake of the DTC (some people dismiss applying for the DTC if they determine they wouldn’t receive the financial value of the credit). Middle- and higher-income Canadians are the primary beneficiaries of the DTC in its current state as a non-refundable tax credit. It is also the DAC’s view that a refundable DTC must be treated as exempt income by provincial/territorial social assistance programs.

EDSC has done some work to actively improve public awareness about the DTC and the RDSP, grant, and bond through a range of outreach activities, including in collaboration with CRA. This includes the delivery of joint informational webinars on the DTC and RDSP/Grant/Bond with the aim of promoting them to individuals who may be eligible but have not yet applied. 50 webinars were delivered last year, many of which were joint presentations with CRA on the DTC. ESDC also promotes information at conferences and events, and via direct engagement with a wide range of community-based stakeholders. DTC pages on Canada.ca were updated in June 2022 to contain more information in plain language and also include links to the CRA gateway Benefits. A landing page for Persons With Disabilities is also under way which will include links to all federal programs and benefits for PWDs. A webinar for PWDs was also held and is now available on YouTube and Canada.ca.

Next Steps and Recommendations

Despite these activities, the uptake of the DTC is relatively low across Canada, suggesting that individuals are missing information and experiencing many barriers during the process of applying for the DTC. The DAC discussed the importance of increasing the uptake of the DTC among working age (18 to 64 years) individuals in Canada. As noted in our previous report, individuals under the age of 18 years and over the age of 64 years comprised the majority (60.6%) of DTC beneficiaries in 2019. Increasing uptake of the DTC in this age group is an important priority, particularly if the Government of Canada chooses to utilize the DTC as a gateway for the forthcoming Canada disability benefit.

Recommendation 14: Design and implement strategies to improve public education about the DTC, with an emphasis on its role as a gateway to disability programs and supports.

Recommendation 15: Systematically identify and address barriers to DTC applications by persons with disabilities, caregivers, and healthcare providers.

Recommendation 16: Make the DTC a refundable tax credit to increase DTC applications, particularly among individuals at lower income levels.

2.2.2. Eligibility

Current Issue

Eligibility criteria for the DTC are inconsistent and lack clarity in certain instances.

Progress to Date

The DAC has raised concern about several eligibility criteria, particularly with criteria related to impairments in mental function and/or episodic conditions. The DAC strongly urged the CRA to discontinue the practice of interpreting the phrase “all or substantially all the time” in DTC applications as 90% of the time. This interpretation meant that to qualify for the DTC, applicants had to show that their impairment(s) affected their basic activities of daily living 90% of the time, which can be difficult for people with episodic and/or mental disabilities. The CRA agreed to exclude explicit reference to 90% in the DTC electronic application. However, the 90% standard remains in the DTC paper application to further define what "all or substantially all of the time" means.

DTC assessors have access to the medical resource guide. The guidelines permit more flexibility in the interpretation of “all or substantially all of the time” by noting that the effects of the impairment must be present and challenging “all or almost all the time” rather than the arbitrary 90% rule.

The DAC has made three further recommendations regarding the CRA’s interpretation of eligibility criteria:

- that the CRA no longer interpret “an inordinate amount of time” as three times the amount of time it takes a person without the impairment

- that the CRA interpret “severe and prolonged restriction” to include impairment in two or more mental functions, when none of the functions creates severe and prolonged restriction on their own

- that the CRA interpret “severe and prolonged restriction” to include impairments in mental functions that are intermittent and/or unpredictable

The changes to the legislation are such that mental functions is looked at on a cumulative basis, so not all functions need to be marked restrictions on their own to qualify. The CRA looks at this category as a whole, however the DAC identified that this needs to be described more explicitly in how this is determined. The CRA updated its manuals and clarification letters to help assessors analyze and collect adequate information to make a determination, noting that the CRA no longer excludes episodic impairments, but they still need to meet the legislated test.

Next Steps and Recommendations

Despite progress made to date, inconsistencies, and ambiguity in eligibility criteria for the DTC persist. The DAC continues to have concerns regarding the interpretation of “all or substantially all” as 90% of the time in the DTC application process for specific condition or cumulative effect eligibility. This interpretation creates difficulties for applicants who have episodic conditions, such as multiple sclerosis, that may not meet the 90% criterion but that still require support from the DTC. Arthritis, diabetes, and depression are examples of other long-term conditions that may be episodic.

Furthermore, there is confusion among providers on how to complete the DTC application for patients with episodic conditions. There is a need to create guidance for practitioners and applicants with respect to those with episodic conditions applying for the DTC to make sure that these conditions can be addressed in applications in a robust, consistent manner, rather than the current model of a point-in-time evaluation. Additional clarity around this interpretation will also be particularly important in the near future in light of increasing cases of long-COVID resulting from previous COVID-19 infection.

Shifting the interpretation of this criterion is supportive of the person-centered, biopsychosocial model of disability outlined above, as it will require the consideration of additional aspects of disability in the DTC application. In line with the proposed shift in the definition of disability, eligibility criteria for the DTC will need to be reexamined in consideration of this new approach.

The DAC also notes concerns with the questions about caregiving that are only included in the mental functions essential for the everyday life section of the practitioner’s portion of the application form. Specifically, this section of the form asks whether the patient has an impaired capacity to live independently without daily supervision or support from others. The DAC questions whether it is appropriate for this question to be included in this section but not in the other sections of the form.

Recommendation 17: Remove the 90% criteria from the DTC paper application and provide a framework for healthcare providers and CRA staff to apply the “all or substantially all of the time” criteria to episodic conditions.

Recommendation 18: Remove questions about caregiving requirements in the mental functioning impairment section of the DTC application.

Study the points of convergence between the eligibility criteria for provincial/territorial programs and the DTC to recognize equivalencies and, ultimately, adopt a standard from Accessibility Standards Canada. This could entail granting recipients of disability benefits from other levels of government automatic eligibility for the DTC (Recommendation 11).

Reframe the definition of disability in the Income Tax Act to shift towards a biopsychosocial model of disability through consultations with persons with disabilities and clinical practitioners (Recommendation 1).

2.2.3. Procedure for Applying

Current Issue

Many challenges exist throughout the process of applying for the DTC, for medical practitioners and applicants, which create barriers to accessing the DTC.

Progress to Date

In previous reports the DAC recommended a cap be placed on the fees that promoters can charge for assisting a person to make a DTC application. In response, the federal government passed the Disability Tax Credit Promoters Restrictions Act. However, the regulations drafted to enforce a cap of $100 for promoters fees have been suspended from implementation pending the outcome of litigation in British Columbia. The DAC has also expressed concern about the high fees that medical practitioners charge for certifying DTC applications.

The DAC has studied the issue of expanding the list of health providers who can assess eligibility for the DTC. The DAC suggested that the CRA develop criteria to guide an expansion of this list. The CRA did not take action to develop these criteria. As a result, the DAC arrived at a simpler solution: that the CRA should not limit the list of eligible providers and that any licensed health provider should be eligible to certify DTC applications. The CRA has not implemented this recommendation.

In response to DAC recommendations, the CRA developed a medical practitioner webinar, which is available on YouTube and Canada.ca. Medical advisors also take the time, whenever a medical practitioner calls the medical practitioner 1-800 line, to educate and explain how to fill out Part B of the T2201. The CRA has created the new position of navigator to help applicants with particularly complex cases. Since the introduction of navigators, along with DTC call centres and digital applications, the CRA has reported a reduction in the number of clarification letters and their associated delays and costs in DTC applications. The CRA has advised that it plans to hire Indigenous navigators to complement the services but has not provided confirmation that these hires have taken place.

Next Steps and Recommendations

The DAC notes that practitioners still experience many challenges with filling out a DTC application. DAC consultations with practitioners highlighted the need for more resources and guidance for practitioners to ensure they can fill out a DTC application accurately for their patients. There is also a need for clarity and consistency across the country with respect to the fees practitioners can charge to complete DTC applications. This is not well understood by either practitioners or applicants, and high fees can be a barrier to applying for and accessing the DTC.

The DAC encourages the CRA to consider offering training opportunities for practitioners to ensure they understand who is eligible for the DTC and how to complete an application. It is important that these training sessions be available in a variety of settings, such as in hospitals, at conferences, and online, to ensure a wide reach of the information. An opportunity exists to create training courses that would allow practitioners to receive continuing education credits.

The DAC, along with consulted practitioners, also supports the idea of having a broader range of professionals, such as social workers, who can fill out all sections of the DTC application form. This recognizes the challenges that applicants experience accessing certain practitioners (such as family doctors) in various regions across Canada and recognizes the differing responsibilities and scope of practices of practitioners across provinces and territories.

Practitioners and applicants also need to be able to easily access information that helps with questions about the application process. This is evidenced by the high call volume to the CRA’s general enquiries line related to DTC claims for self or for transfers from dependents in 2021 and 2022 (with a notable 5% increase from 2021 to 2022). Reasons for these calls are summarized in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Reasons for Calls to the CRA General Enquiries Line in 2021 and 2022

| Issue related to CRA enquiry | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Eligibility issues | 12,243 (10%) | 17,947 (13%) |

| How to apply for DTC | 18,145 (14%) | 22,583 (17%) |

| How to claim DTC | 13,507 (10%) | 22,595 (17%) |

| Repayment Assistance Program requests | 17,405 (14%) | 12,272 (9%) |

| Status updates | 45,373 (36%) | 42,374 (32%) |

| Other | 20,523 (16%) | 15,787 (12%) |

| Total calls | 127,196 | 133,558 (up 5% from 2021) |

While the DAC appreciates that there is a high volume of calls to the CRA regarding questions about the DTC application, practitioners and applicants need to be able to have their questions addressed on a more immediate basis to prevent delays in completing and submitting an application. As recommended in 2020, this should include the development of a designated call line in addition to the regular CRA phone line, with specially trained staff to address more complex questions relating to DTC eligibility criteria, impairment in mental functions, applications on behalf of children and DTC appeals (Disability Advisory Committee, 2020a).

An expansion of both the number and role of CRA navigators is also needed. The navigator role, created in April 2021, is free of charge and has the purpose of supporting applicants and their representatives in navigating complex circumstances in the DTC application process. The CRA currently has three navigators, one for each of the three tax centres. The DAC notes that while the navigator role is a positive step forward, applicants do not have direct or easy access to the navigators. Applicants have to contact the CRA general enquiries line before being connected to a navigator by a call centre agent. The capacity of navigators to support CRA call centre agents with calls is currently quite low, with only 600 of the 133,000 DTC-related calls being directed to navigators in 2022. Improvements in the ability of practitioners and applicants to access CRA staff and navigators is much needed and will be particularly important to address questions pertaining to the newly launched digital DTC application in a timely manner.

In expanding the navigator role, the DAC discussed the potential for certain navigator functions to be outsourced to other organizations with existing capacity and expertise. There are several charities, community living groups, caregiver support groups, constituency offices for members of Parliament and non-profit organizations that have resources, how-to guides and the ability to provide support on how to navigate the process of applying for and claiming the DTC for no charge. Examples (not comprehensive) of organizations providing free support, information and advice include organizations like the Multiple Sclerosis Society, Ostomy Canada Society, Momentum, Independent Living Canada, and Manitoba Possible. One organization to note is Plan Institute, which provides free one-to-one support and resources to help people become informed, apply for the DTC and open a registered disability savings plan. In the past, the Plan Institute has partnered with IDC/BCANDS to support Indigenous Peoples with disabilities in applying. Providing support and resources to these types of organizations to support navigator roles could be a cost-effective approach to reaching people in the community.

In addition, the CRA should ensure accessibility in its communications about the application process. Information should be available in plain language and adhere to universal design, in consultation with people with disabilities (see recommendations 12 and 13).

Recommendation 19: Improve resources, knowledge, and training to support healthcare providers in filling out DTC certificate applications.

Recommendation 20: Expand the range of professionals who can fill out the DTC certificate applications to any licensed health or social services provider.

Recommendation 21: Increase the number of CRA navigators, and highlight and enhance the navigator role, to improve transparency and reduce barriers to applying for the DTC. This could include outsourcing parts of the navigator role to external organizations with existing expertise and capacity.

Recommendation 22: Develop a distinct accessible support pathway for the newly launched, fully digital application.

Recommendation 23: Provide guidelines for practitioners regarding fees for completing the DTC certificate application.

2.2.4. Objections and Appeals

Current Issue

When initial applications are not accepted by the CRA, an applicant may file an objection with the CRA, which can then be escalated by filing an appeal with the Tax Court of Canada. Recommended guidance to claimants is to provide further information from a medical practitioner, or to file an income tax objection. However, guidance elsewhere suggests that, even if one is not sure if they qualify, they should apply. Due to lack of knowledge of any determination rules beyond what is publicly available, applicants may choose to object, regardless of the reason listed on the notice of determination. Data on the conditions and sociodemographic characteristics of those who have an application rejected is not made publicly available. Data on the number of objections, though used internally, is also not publicly available. This does not allow for a detailed look at how the application process can be improved to reduce applications that might be initially declined before later being accepted.

Progress to Date

The CRA advised the DAC that its Appeals Branch and its navigators track data on the number of objections and appeals received, approved, and rejected. In their 2022 report, the DAC requested that the CRA share the data it currently collects on the number of objections and appeals, their nature and the time taken to resolve them.

Next Steps and Recommendations

Being able to quantify the number of rejections, and the reasons for rejections, would allow the CRA to determine best methods to improve the DTC application process. This would reduce the number of applicants who later get accepted after having to submit follow-up paperwork following an initial rejection, while also reducing the number of applicants who do not meet eligibility criteria in the first place from applying. The DAC encourages the CRA to collect and release this data, so interested individuals can recommend enhancements or highlight criteria to reduce the risk of a rejected application.

Recommendation 24: Provide public data on the number of, and reasons for, reviews of, and objections to, DTC rulings by the CRA.

2.2.5. After Receiving the DTC

Current Issue

Low uptake of the DTC results in low uptake of the programs linked to receipt of the DTC.

Progress to Date

In previous reports the DAC has emphasized the importance of collecting data about DTC applicants and recipients to obtain information about the role of the DTC as a gateway to other disability benefits and programs, rather than just a credit to reduce an individual’s tax burden. The DAC has consistently raised concerns that this gateway function is not well understood or utilized by potentially eligible individuals. The DAC has recommended that the CRA improve communications with potential applicants about the DTC’s gateway function.

The DAC has been advised that the creation of an interdepartmental advisory committee would be a political decision. The DAC advises the Minister of National Revenue. The Minister of Diversity, Inclusion and Persons with Disabilities has their own disability advisory group, which has not currently identified the RDSP or DTC as a priority. In the absence of a multi-ministry committee, the DAC has been informed that engagement between departmental officials is ongoing. ESDC, CRA, and Finance officials meet regularly to discuss issues related to the DTC and RDSP, as applicable. The DAC acknowledges these informal channels but recommends formalized and transparent interministry processes related to the RDSP, given the direct connection to the DTC.

Next Steps and Recommendations

The DTC has a critical function as a gateway to accessing many other tax credits, benefits, and programs provided by the Government of Canada. The DAC notes that the awareness of this fact is lacking among those that are potentially eligible to apply for the DTC. Without this knowledge, the time, cost, and resources needed to apply for and access the DTC may outweigh the benefit of receiving the DTC. This is particularly relevant for individuals at a lower income level, as the non-refundable design of the DTC provides little financial benefit to those that do not owe income tax. The DAC anticipates that providing a more comprehensive understanding of the suite of programs individuals could access once they successfully obtain the DTC would increase the number of individuals applying for and subsequently accessing the DTC. In line with this, the DAC suggests that information about the DTC be shared publicly and with providers that market the DTC as a gateway benefit, rather than just a tax credit.

To make it easier for individuals that receive the DTC to access the associated gateway programs, the DAC discussed the importance of issuing an official DTC certificate. Currently, DTC recipients receive a two-page, text-heavy letter that confirms their receipt of the DTC. This letter may contain information about the recipients’ disability that they may not want to disclose to institutions (such as banks) that they will need to consult with to access gateway programs. A one-page official DTC certificate would protect the privacy of the DTC recipient and simplify the process of providing proof of receipt of the DTC for both recipients and downstream providers. A standalone bona fide certificate to the recipient would help distinguish this from the approval letter and would reduce confusion among recipients.

Additionally, the DAC had many discussions regarding the role of the DTC as a gateway for other programs and benefits provided by the Government of Canada. If the DTC is to continue to be the gateway to these programs, and potentially to new programs created in the future such as the Canada disability benefit, the considerations regarding design of, and eligibility for, the DTC discussed above must be implemented. These improvements will not only increase uptake of the DTC and linked programs but will also establish more consistent uptake across provinces and territories, which is essential to promote equity of access across Canada.

The DAC also discussed the design of a registered disability savings plan (RDSP), an important financial tool for DTC recipients. The DAC has many concerns regarding the current RDSP legislation, as summarized below:

- people cannot fully benefit from funds in their RDSPs due to the combined effect of the lifetime disability assistance payment formula and the repayment obligation associated with the assistance holdback amount

- people who are considered incapable of signing a contract may not be able to open an RDSP

- there are many people who do not live long enough to benefit from the funds in their RDSP. It is unclear what happens to an individual’s estate and the beneficiaries of an estate.

As such, the DAC recommends a comprehensive overview of RDSP legislation. Specific aspects of the RDSP that the Department of Finance Canada and ESDC should consider changing to address current concerns with the RDSP include the following:

- adjust grant and bond amounts on an annual basis to match inflation

- create a public RDSP-bond-only option with automatic enrollment of DTC holders who have yet to open an account

- include RDSP modernization in the financial security pillar of the Canada Disability Action Plan

- review the process of accessing funds from an RDSP

Recommendation 25: Coordinate a multi-ministry committee (consisting of representatives from the CRA, ESDC and the Department of Finance Canada) to review registered disability savings plan legislation.

Recommendation 26: Provide an official DTC certificate document to DTC recipients.

Design and implement strategies to improve public education about the DTC, with an emphasis on its role as a gateway to disability programs and supports (Recommendation 14).

3. Conclusion

The DAC advises the CRA on interpreting and administering tax measures for Canadians living with disabilities in a fair, transparent, and accessible way. To this end, the DAC has provided a range of different recommendations in the past five years. Many policy frameworks, processes and services have been improved because of the DAC’s proposals. However, as the report card in Appendix C shows, some important challenges remain to be addressed to improve DTC uptake, eligibility, and accessibility, especially for its gateway function to other disability supports and services. This holds significant and immediate importance with the design of the federal Canada disability benefit. Whereas the CRA has made progress in improving engagement and service provision to populations of special consideration, significant effort is required to better serve Indigenous Peoples, Black people, and racialized communities, and address regional discrepancies. It is imperative that the CRA ensure future changes to the design and implementation of programs are co-designed with underserved groups, individuals with expertise, including those with lived experience, and relevant practitioners.

The DAC recognizes that its scope and potential impact is limited to policy and administrative processes falling within the mandate of the minister of national revenue and the commissioner of the CRA. However, to successfully improve tax measures for Canadians living with disabilities, other agencies and departments in the federal government as well as provincial and territorial governments need to co-operate and actively collaborate through joint committees or other cross-organization structures with the CRA and take into consideration the recommendations of the DAC.

References

- Canada Revenue Agency (2020). Tax measures for persons with disabilities. Disability-related information (PDF, 842 KB). Government of Canada website

- Canada, S. o. (2017). Breaking Down Barriers: A critical analysis of the Disability Tax Credit and the Registered Disability Savings Plan

- Canadian Medical Association (2013). Canadian Medical Association Submission on Bill C-462 Disability Tax Credit Promoters Restrictions Act

- Disability Advisory Committee (2019). Enabling Access to Disability Tax Measures (PDF, 836 KB)

- Disability Advisory Committee (2020a). The Client Experience

- Disability Advisory Committee (2020b). Readout: Disability Advisory Committee Meeting - November 10, 2020. Canada Revenue Agency

- Dunn, S., & Zwicker, J. (2018). Why is Uptake of the Disability Tax Credit Low in Canada? Exploring Possible Barriers to Access. The School of Public Policy Publications, 11

- Income Tax Act, § 118.3 (1985)

- One-time payment to persons with disabilities (2020)

- Publication and open data portal

- Disability Tax Credit Statistics – Canada.ca

- Disability Tax Credit Statistics – (2022 Edition) 2012 to 2021 Calendar Years - Open Government Portal (canada.ca)

Appendix A

The Disability Tax Credit Explained

The DTC is a non-refundable tax credit designed as a horizontal tax equity instrument to provide tax relief for the additional costs that persons with severe disabilities may face as barriers to participation in society (Canada, 2017; Disability Advisory Committee, 2019; Dunn & Zwicker, 2018). The purpose of the DTC is to reduce the income tax burden for persons with severe disabilities who incur additional costs (often non-itemizable) that are not experienced by persons without disabilities (Disability Advisory Committee, 2019). The design of the credit is based on the assumption that persons with severe disability incur a range of these indirect or non-itemizable disability-related costs that they are not able to claim under the medical expense tax credit (Disability Advisory Committee, 2019). Examples of these types of costs include hiring a trained caregiver or paying higher prices due to reduced options for shopping, custom clothing, or special transportation. Also, the DTC design is based on the assumption that persons with severe and prolonged disabilities have their income-earning capacity negatively affected because of the extra time they must devote to activities of daily living due to their severely disabling condition.