Evaluation of the Future Skills program - 2018 to 2023

From: Employment and Social Development Canada

On this page

- Alternate formats

- List of tables

- List of figures

- List of abbreviations

- Executive summary

- Management response and action plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Background

- 3. Evaluation context

- 4. Ongoing need for the program

- 5. Program outcomes

- 6. Governance

- 7. Performance measurement

- 8. Conclusions

- 9. Recommendations

- 10. References

Alternate formats

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

List of tables

- Table 1: Recommendation #1 management action plan items

- Table 2: Recommendation #2 management action plan items

- Table 3: Recommendation #3 management action plan items

- Table 4: Program funding (in millions $, rounded)

- Table 5: Program Full-Time Equivalents (FTEs)

- Table 6: FSC - Number of projects and value of investment by provinces/territory

- Table 7: FSC - Funding by Funding round title (as of December 31, 2022)

- Table 8: FSC - Funding and Projects by sector, as of June 2022

- Table 9: FSC - Projects by Innovation Ambition and Horizon

- Table 10: FSC - Projects by targeted underrepresented and equity-seeking groups

List of figures

List of abbreviations

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- EWG

- Evaluation Working Group (Evaluation, SEB and POB)

- FSC

- Future Skills Centre (Program’s unique contribution recipient)

- LMIC

- Labour Market Information Council

- OECD

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development

- POB

- Program Operations Branch (ESDC)

- SEB

- Skills and Employment Branch (ESDC)

Executive summary

The Future Skills program (the Program) aims to achieve collaboration, innovation and transformation in Canada through research and investments with provinces and territories, and non-profit organizations to offer access to in-demand quality training that addresses the changing nature of work, especially for underrepresented groups.

This is the first evaluation of the Program since its start in fiscal year 2018 to 2019. Formative in nature, the evaluation examines the ongoing need for the Program, its governance structure, and the extent to which progress has been made towards its objectives. Evaluation findings come from multiple lines of evidence and cover the period from 2018 to 2019 to 2022 to 2023. Over this period, the level of annual expenditure increased from $25 million in 2018 to 2019, to $75 million starting in 2020 to 2021, for a total of $300 million.

Ongoing need and demand for the program

- Canada’s skills development ecosystem continues to face ongoing challenges in the area of job-related training and labour market information.

- The labour market is evolving, and adjustments are needed to make sure Canadians, and the Canadian economy can thrive in a rapidly changing environment. There is an ongoing need for information and evidence about solutions for re-skilling or up-skilling to enable workers to adapt to changes in the labour market.

- Underrepresented and underserved groups in the labour market continue to face more barriers. The Program’s focus on these groups remains in line with government priorities.

- There is an ongoing effort to continue to avoid duplication and complement existing programs and initiatives in the skills and training ecosystem.

Program outcomes

- The COVID-19 pandemic presented challenges in the early years of the Program and resulted in delays to achieve the Program's outcomes.

- The Program has been effective in engaging a pan-Canadian network of diverse stakeholders and experts across the skills development ecosystem.

- The Program is setting the stage for innovation in the skills development ecosystem. But the extent to which it is experimenting innovative approaches is unclear and may be too early to assess.

- Early results show that there was knowledge developed for the skills development ecosystem. But not enough evidence is available to assess the usefulness of the knowledge produced.

- The Program has undertaken a variety of knowledge mobilization activities to help inform and influence skills-related policies and programs, the impacts of these efforts on policies and programs are unclear.

- Most funded projects focus on underrepresented, disadvantaged and equity-deserving groups. But it is too early to assess the impacts on these groups.

Governance structure

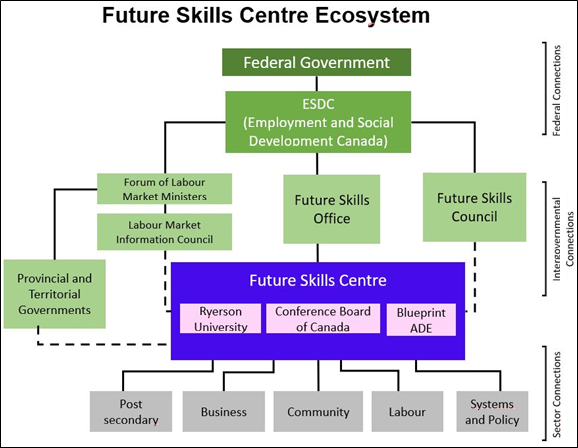

The design of the Future Skills Program was based on 3 pillars with distinct roles and responsibilities to support the objectives. The first and central pillar is the Future Skills Centre (the Centre). The Centre was established in February 2019 via a single Contribution Agreement between ESDC and the Toronto Metropolitan University (then Ryerson University). A consortium was created between the Toronto Metropolitan University, the Conference Board of Canada, and Blueprint-ADE.

The second pillar is the Future Skills Council, an advisory body composed of subject-matter experts in skills development. The Future Skills Office (within Employment and Social Development Canada) is the third pillar.

- The third-party delivery model is seen as effective for delivering on the objectives of the program. But roles and responsibilities of the department and the Future Skills Centre aren't always clear.

- The Future Skills Council has fulfilled its mandate.

- The consortium model governing the Future Skills Centre is a non-traditional approach to achieving the objectives of a federal program. But, there are challenges related to lines of accountability and lack of clarity in responsibilities with this type of partnership.

Performance measurement

- Data available from the Future Skills Centre meets the reporting requirements of the Contribution Agreement.

- But, the information isn't sufficient for ESDC to monitor and report on performance over time and measure impacts, particularly on underreprensented groups.

Recommendations

- Continue to improve and strengthen data collection and reporting on the Program’s performance to support better decision-making.

- Strengthen knowledge synthesis and mobilization activities for evidence generated by the Future Skills Centre.

- Take steps to clarify the role of ESDC and increase its visibility to support efforts to mobilize knowledge and influence skills-related policies and programming.

Management response and action plan

Overall management response

Management accepts the recommendations outlined in the Evaluation of the Future Skills Program. We will use the evaluation findings to inform continuous improvement of the program design and delivery. The Program aims to support Canada’s skills policies and programs to adapt and meet the evolving needs of job seekers, workers and employers within a changing world of work. It has a unique delivery model through the creation of the Future Skills Centre, an independent innovation and applied-research centre. The Centre identifies emerging skills trends, tests and implements new approaches to skills assessment and development, and disseminates evidence widely to inform future programming.

Future Skills’ objectives align with departmental priorities to strengthen the training systems in Canada to build human capital; to address the changing way that people work; and to foster equity, diversity and inclusion. The program also supports other key government priorities such as sustainable jobs, addressing labour shortages, and digital economy.

Evaluation findings show that there is an ongoing need for a program that is future oriented, evidence-based, with a focus on innovation, experimentation and inclusion in the skills and training development ecosystem. Through its delivery model, the Program has been effective in engaging a pan-Canadian network of multi-sectoral stakeholders and experts across the skills development ecosystem enabling the Program to complement existing programs and initiatives and avoid duplication. While the program has many ongoing projects, the full impact has yet to be realized as the bulk of the projects are due to complete in fiscal year 2023 to 2024.

Significant efforts were already in progress during the time of the evaluation aligned with the findings of the report, including improving performance management practices, strengthening knowledge synthesis, and increasing Program visibility.

Recommendation #1

Continue to improve and strengthen data collection and reporting on the Program’s performance to support better decision-making.

As the Program continues to mature and an increasing number of funded projects are reporting on results, it will be important to improve upon the performance measurement strategy. The strategy would benefit from focusing more on collecting consistent and meaningful outcome data and effectively utilizing the performance data to support the management and the accountability of the Program.

The Program should explore opportunities to collaborate with the Centre to better align and streamline data collection efforts around key performance indicators. The Program could also explore the Centre’s Research, Evaluation and Knowledge Mobilization’s “Learning and Evaluation Database” to find potential opportunities to support more timely, targeted, and advanced analysis of project information to support performance measurement needs.

Also, the Program could give further consideration to how it uses the performance information collected to better support decision-making. Indeed, it isn't clear how and to what extent the collected performance information from the Centre is currently used.

Management response #1

Management agrees with this recommendation. The Department had already been working on improving and strengthening performance measurement practices. Over the past year, ESDC undertook an in-depth analysis of existing data collection and reporting practices in relation to the requirements outlined in the Performance Information Profile and the contribution agreement. The review identified areas for improvement, and steps will be taken to strengthen the Program’s performance measurement strategy going forward. The Program will also explore the possibility for leveraging the Centre’s “Learning and Evaluation Database” for meeting identified reporting gaps and improving overall performance measurement of the Program.

ESDC will continue to monitor the Centre’s results with respect to quarterly data reporting requirements as outlined in the contribution agreement. As well, ESDC will continue to review reporting requirements and expectations through the contribution agreement and Performance Information Profile to collect relevant data to support continuous Program improvement.

| Section | Management action plan | Estimated completion date | Status | Accountable lead(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | Review data collection and performance measurement strategies to identify gaps and opportunities for improvement. | June 2023 | In progress | SEB |

| 1.2 | Update reporting requirements outlined in the contribution agreement to address data collection and reporting gaps identified in 1.1. | September 2023 | In progress | POB lead supported by SEB |

Recommendation #2

Strengthen knowledge synthesis and mobilization activities for evidence generated by the Future Skills Centre.

A key program objective of the Future Skills Program is to support transformative labour market policy and program innovation to ensure that Canada’s labour market and training systems remain future-fit. To that end, the Program aims to:

- find emerging in-demand skills now and into the future;

- support experimentation by prototyping, testing and rigorously measuring innovative approaches;

- publicly disseminate evidence on what works; and

- foster the enabling conditions for replication and scaling.

The Program has demonstrated significant progress in identifying skills and supporting experimentation. It has also effectively established relations with provincial, territorial, and federal partners through the work of the Centre and the Office. With the majority of projects funded by the program ending in fiscal year 2023 to 2024, the Program is encouraged to place greater emphasis on producing a more comprehensive analysis and reporting on lessons learned on what is working and not working to foster the enabling conditions to meet job seekers, workers and employers evolving needs. The Program should also aspire to more cohesive knowledge synthesis and mobilization to maximize insights from evidence generated by the Centre to support replication and scaling of promising practices.

Management response #2

Management agrees with the recommendation. The Department has begun working on improving the monitoring of the knowledge synthesis and mobilization activities generated by the Future Skills Centre. For example, ESDC will identify opportunities to support the Centre’s dissemination efforts through the Forum of Labour Market Ministers. The outputs from the Future Skills Centre, including but not limited to knowledge synthesis and mobilization strategy and products will be part of ongoing monitoring activities. The Department will assess whether related outputs provide quality policy and program design insights generated through knowledge synthesis activities such as but not limited to reports, webinars, and presentations.

| Section | Management action plan | Estimated completion date | Status | Accountable lead(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 | Review and amend the contribution agreement to better capture knowledge synthesis activities. | September 2023 | In progress | POB with support by SEB |

| 2.2 | Review Future Skills Centre outputs from knowledge synthesis activities and assess quality of policy and program design insights. | March 2024 | In progress | SEB lead supported by POB |

Recommendation #3

Take steps to clarify the role of ESDC and increase its visibility to support efforts to mobilize knowledge and influence labour market policies and programming.

In the implementation of the Future Skills initiative, internal and external engagement and communications activities were mainly carried out by the Future Skills Council and Future Skills Centre. This has resulted in a lack of awareness and clarity about ESDC’s role to fulfill the Program’s objectives with respect to supporting transformative labour market policy and program innovation. As the Program continues to mature and more knowledge is produced, the role and visibility could affect its efforts to influence government policies and programs.

Furthermore, working with the Future Skills Centre to make sure roles and responsibilities are clearly defined can help ensure better support and complementarity of eachothers’ work and minimizes inefficiencies associated with potential duplication.

Management response #3

In the initial implementation of the initiative, the Department prioritized visibility of the Future Skills Council and Future Skills Centre to reinforce the importance of cross-sectoral collaboration to identify emerging workforce and skills trends and to develop solutions to real world challenges. With the launch of the Program, ESDC established bilateral relations with federal partners, such as Public Safety (on the National Cyber Security Strategy), and with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (on the Blue Economy). ESDC also established an interdepartmental Jobs, Skills and Training Table to foster dialogue on whole-of-government priorities. This is besides ongoing bilateral (with provincial and territorial governments) and multilateral (through the Forum of Labour Market Ministers) engagement to ease collaboration on areas of mutual interest.

Management agrees with the recommendation. The Department will build on strong working relations developed with federal, provincial and territorial governments to augment efforts to support the adoption of evidence generated by the Centre into future policy and program design. ESDC will develop a plan to leverage knowledge generated to strengthen collaboration with different orders of government and other policy leads. The Department will reinforce clarity of roles and responsibilities between ESDC and the Centre. This will mitigate risks of duplication and maximize ESDC’s contribution to support transformative labour market policy and program innovation to ensure that Canada’s labour market and training systems remain future-fit.

| Section | Management action plan | Estimated completion date | Status | Accountable lead(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1 | ESDC will develop and implement a plan to strengthen its visibility and better communicate its role in supporting the adoption of evidence generated under Future Skills into policy and programs. | March 2024 | In progress | SEB |

1. Introduction

This report presents the findings of the first evaluation of Employment and Social Development Canada’s Future Skills program (hereafter called the Program).

The objectives of the evaluation are to examine :

- the ongoing need for the Program,

- the extent to which progress has been made towards the Program's objectives and

- the Program's governance structure.

The evaluation was completed in compliance with the Financial Administration Act and the Treasury Board Policy on Results.

2. Background

2.1 Program objectives

The Program aims to provide access to in-demand quality training that addresses the changing nature of work, especially for underrepresented groups. It does so by achieving collaboration, innovation and transformation in Canada through research and investments with provinces and territories, as well as not-for-profit organizations. Based on evidence generated from the Program, individuals and organizations involved in skills-related policies and programs will adapt and keep pace with the changing labour market to meet job seekers’, workers’ and employers’ evolving needs. In particular, the Program aims to achieve the following outcomes:

- identify emerging in-demand skills now and into the future

- support experimentation by prototyping, testing and rigorously measuring innovative approaches

- publicly disseminate evidence on what works, and

- foster the enabling conditions for replication and scaling.

2.2 Program resources

As announced in Budget 2017 and 2018, the Program’s total budget amounts to $375M for the period from 2018 to 2019 to 2023 to 2024 (Table 4).

Program funding gradually scaled up in the first two fiscal years and reached $75 million per year as of fiscal year 2020 to 2021. The following tables give actual and planned resources information for the first 6 fiscal years of the program from 2018 to 2019 to 2023 to 2024.

The evaluation covers only the 5-year period from 2018 to 2019 to 2022 to 2023.

| Fiscal Year | 2018 to 2019 Actual | 2019 to 2020 Actual | 2020 to 2021 Actual | 2021 to 2022 Actual | 2022 to 2023 Planned | 2023 to 2024 Planned | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operation and Maintenance | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 13.6 |

| Grants and Contributions | 22.7 | 47.7 | 72.9 | 72.7 | 72.7 | 72.7 | 361.4 |

| Total | 25 | 50 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 375 |

- Source: Chief Finance Office Branch.

| Fiscal Year | 2018 to 2019 Actual | 2019 to 2020 Actual | 2020 to 2021 Actual | 2021 to 2022 Actual | 2022 to 2023 Planned | 2023 to 2024 Planned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program Full-time Equivalents | 1 | 29 | 32 | 24 | 14 | 14 |

- Source: GCInfobase.

2.3 The 3 pillars of Future Skills

The design of the Future Skills Program is based on 3 pillars with distinct roles and responsibilities to support its objectives. The first pillar is Employment and Social Development Canada, where responsibilities are shared between the Skills and Employment Branch and Program Operations Branch. The Future Skills Council is the second pillar, while the Future Skills Centre is the third and central pillar.

2.3.1 Employment and Social Development Canada

2.3.1.1 Skills and Employment Branch

The Future Skills Program is a part of Employment and Social Development Canada portfolio. The main responsibility of ESDC Skills and Employment Branch (SEB) about the Program is to share knowledge and lessons learned across the federal government and with provincial and territorial partners. Its responsibility also includes providing a secretarial function to the Future Skills Council, drawing lessons learned, and working with partners and stakeholders to support the adoption of evidence generated by the Program into policy. The group responsible for carrying out this work is “the Future Skills Office”.

2.3.1.2 Program Operations Branch

Program Operations Branch (POB) handles administering the Contribution Agreement between ESDC and the Future Skills Centre. POB’s role is to set up and monitor adherence to the terms of the Contribution Agreement and that funds are appropriately used. POB is also responsible for collecting all required reports (quarterly, annual and audit reports) from the Centre and transmitting them to SEB.

2.3.2 Future Skills Council

In 2019, the Future Skills Council brought together 15 leaders from public, private, labour, Indigenous and not-for-profit organizations to identify common priorities from across sectors and provide advice on emerging skills and workforce trends. 3 seats on the Council were designated for First Nations, Inuit and Métis representation. The council engaged organizations across the country as well as international experts to understand how innovation, technology and other events affect people and communities.

Council members’ tenure ended June 30, 2021, after the completion of the Council’s mandate.

2.3.3. Future Skills Centre

The Future Skills Centre (the Centre) was established in February 2019 via a Contribution Agreement between ESDC and the Toronto Metropolitan University (then Ryerson University) whereby a consortium was created between the Toronto Metropolitan University, the Conference Board of Canada, and Blueprint-ADE. The Centre received $360 million over 6 fiscal years of which it must redistribute at least 70% as project-based funding across Canada.

The Centre is an innovation and applied research project whose objective is to foster a more responsive skills development ecosystem and contribute to a more agile, adaptable workforce in Canada. As a pan-Canadian organization, the Centre works with partners across Canada to understand how global trends affect the economy and to identify what skills working-age adults need to thrive within an ever-evolving environment. Based on these insights, and with its partners, the Centre tests and measures innovative approaches to skills development and training to learn what works.

Specifically, the objectives established in the Contribution Agreement are as follows:

- Partnerships: develop and expand a pan-Canadian, cross-sectoral network of diverse partners and stakeholders across the skills development and training ecosystem to leverage expertise and investments, build capacity, and identify shared priorities.

- Research to identify in-demand skills: build a new evidence base of the skills sought and required in the workplace now and in the future. The Centre will conduct cutting-edge research to anticipate and rapidly respond to demands for skills, increasing opportunities for diverse job seekers and strengthening informed training and decision-making.

- Evaluation of innovative approaches: prototype, test, and rigorously measure innovative approaches to skills development by developing a diverse portfolio of projects that will identify, implement, replicate, and rigorously evaluate local practices, training models, approaches, and tools to generate evidence about what works.

- Dissemination and knowledge mobilization: publicly and widely disseminate information, analysis and evidence on in-demand skills and promising solutions to build capacity, inform and support future investments in skills development, build and strengthen the national community of practice, and drive systems change.

3. Evaluation context

3.1 Evaluation coverage

This evaluation covers the 5-year period from April 2018 to March 2023. It was completed in compliance with the Financial Administration Act and the Policy on Results.

This is the first evaluation of the Program since its inception. Given early delays in the Program’s implementation and, above all the COVID-19 pandemic, the focus of the evaluation is more formative than summative in nature: it is based mainly on the delivery of the Program and the roles of partners. The program impacts could not be assessed as they have yet to be achieved and reported on. It takes time to test new approaches, observe and measure their impacts and disseminate the results. With only a limited number of projects completed recently, early evidence of program impacts could not be examined.

3.2 Objectives, scope, and methodology of the Evaluation

The evaluation sought to assess the extent to which the Program has been able to progress towards its objectives via the following 4 questions:

- What is the relevance of the Program within Canada’s skills and training ecosystem, and how does it align with other models and complement similar initiatives in provinces and territories?

- To what extent has the Centre and the projects it has funded contributed towards realizing its key objectives to improve knowledge, test innovative approaches and widely disseminate evidence?

- How effective is the program design for developing skills development approaches that are more inclusive and responsive to underrepresented and disadvantaged groups?

- Are there any lessons learned from the governance and its impact on the Program? In terms of (a) How effective is the consortium approach for program delivery by the Centre? And (b) To what extent did activities performed by the Future Skills Council influence the Program during its initial implementation stage?

The evaluation plan was designed in consultation of the Evaluation Working Group to complement the evidence gathered in the internal Future Skills Review (hereafter called the “two-year review”) conducted between 2020 and 2021. Besides, the evaluation used 3 lines of evidence :

- The Literature review included Canadian academic journal articles and the grey literature published since 2015 including provincial/territorial governments reports and data available from Statistics Canada. Further, information about similar programs in other countries were also explored. Key search terms included skills, skills development, employment training, future skills, labour market, workforce development, and re-skilling and up-skilling. A total of 59 sources were included as part of this review.

- 29 Key informant interviews were conducted with program stakeholders divided into two groups:

- Internal stakeholders (n=14) included representatives of the Centre (n=9), the Office (n=4), and the Future Skills Council (n=1).

- External stakeholders (n=15) included representatives of provincial and territorial governments, and Indigenous organizations (n=7), as well as representatives of regional stakeholder organizations, and other federal government departments and agencies (n=8).

- The following scale was used to show the significance of the interview findings. The percentages correspond to the relative weight of responses from key informants who held similar views:

- “All/almost all” – findings reflect the views and opinions of 90% or more of the key informants in the group.

- “Most” – findings reflect the views and opinions of at least 75% but less than 90% of key informants in the group.

- “Majority” – findings reflect the views and opinions of at least 51% but less than 75% of key informants in the group.

- “Some” – findings reflect the views and opinions of at least 25% but less than 50% of key informants in the group.

- “A few” – findings reflect the views and opinions of at least two, but less than 25% of key informants in the group.

- The Documents and Administrative Data review examined information produced since the Program’s start in 2018 such as:

- Examples of knowledge mobilization activities carried out by Future Skills Office.

- Future Skills Council meeting records of discussions and Final report.

- Future Skills Centre documents (Strategic plan, Business plan, Contribution agreement, Project evaluation reports, quarterly activity reports, etc.)

- Future Skills partners’ documents (Developmental Evaluation Summary, Blueprint Evaluation reports, Blueprint annual report)

- Administrative data and documents such as Program’s Performance Information Profile, Treasury Board submissions, Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports.

3.3 Limitations to the evaluation

Some limiting factors affected the breadth and quality of evidence available to inform this evaluation.

First, the focus of the evaluation had to be realigned on delivery and outputs of the Program, rather than on its outcomes (either immediate or intermediate). Given early delays in the Program’s implementation and, above all the COVID-19 pandemic, more time is needed to have enough completed projects to inform impacts. As of January 1st, 2023, 14% of all initiated projects were complete (33 out of 230 projects). Most projects are still in progress and little evidence is available on their outcomes. This applies particularly to projects meant to implement replication and scaling-up of successful skills development innovative approaches.

The original evaluation approach was modified to increase efficiency and avoid duplication. So, the survey of stakeholders was cancelled with the expectation to use the results of the survey conducted by the Program, as part of the two-year review. But the very low response rate to this survey (1.37% or 126 responses) prevented its use to inform the evaluation given the lack of reliability of the data collected. This effectively limited the number of lines of evidence to inform this evaluation to 3.

The fact that the information provided by the Future Skills Centre to ESDC, over the years, isn't consistent limited the documents and administrative data review. Also, there is no standard measurement of projects funded by the Future Skills Centre, so comparison and analysis are difficult. Tables presented in the evaluation report include the most recent information provided by the Future Skills Centre. The Centre changed its information reporting format for quarterly activity reports in year 5, so overtime trends and tracking are not possible and limits the analytical possibility.

4. Ongoing need for the Program

Traditionally, Canada’s skills development ecosystem has delivered skills training and employment supports through two avenues: education systems before workforce entry, and employment assistance for those in the workforce who encounter unemployment. While both are important, the literature and experts in this area point to the need for a third avenue: a system-wide approach to skills development that enables adaptation to changes in the labour market, gradual or sudden, through continuous learning.

The Future Skills Program was designed to support Canada’s skills development systems in being future oriented, evidence-based and equitable. The Program is part of the Government of Canada’s plan to build a resilient and confident workforce that reflects the rapidly evolving nature of work. Following recommendations from Canada’s Advisory Council on Economic Growth and the Forum of Labour Market Ministers, the federal government launched the Future Skills Program, in 2018, to effectively target investment in skills and development training solutions for Canadians. It embraces user-centred design principles to inform the adoption of proven practices and evidence on skills development approaches to ensure that Canada’s policies and programs are prepared to meet Canadians’ changing needs.

Finding 1. The labour market is evolving and adjustments are needed to ensure Canadians and the Canadian economy can thrive in a rapidly changing environment. There is an ongoing need for information and evidence about solutions for re-skilling or up-skilling to enable workers to adapt to changes in the labour market.

The literature reviewed indicates that the economy in Canada and abroad is changing rapidly, which has a profound impact on the nature of work and jobs of the future. Some major factors influence the labour market, including technological change, globalization, demographic shifts, climate change, as well as the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath. These factors have also affected the skills and qualifications needed to enter and grow in the workforce.

- Technological Change: Advances in Artificial Intelligence, robotics, and other technologies are pushing the frontier of automation, and threaten to displace workers in a range of jobs and tasks. Rapid technological advancement increases the pace of skill obsolescence. These advancements and new business models are affecting job seekers’, workers’ and employers’ ability to adapt and keep up with the pace of change.

- Globalization: For the OECD (2019), there is an expectation that technological advance combined with globalization could result in a larger number of “workers being displaced from their jobs because of skills obsolescence”. But “substantial contraction of employment is unlikely” mainly because these factors not only destroy jobs but also create and transform them. This reinforces the need for supporting workers (adversely affected by global trade) as they adapt to changing economic realities. This in turn enhances resilience of the labour market to “effectively prepare for a range of potential futures”.

- Climate Change: Climate change is having significant adverse effects on Canada and the world. These effects are most heavily felt by marginalized groups, contributing to increases in pre-existing social inequalities. Jobs and skills needed to transition to a more climate-friendly economy require re-skilling and up-skilling, especially among those in jobs related to natural resources extraction.

- Demographic Shifts: Canada’s labour market challenges are projected to compound as the population continues to age. The Canadian labour force among the working-age population is now the oldest it has ever been, with more than 20% of the working-age group being between the ages of 55 and 64 according to Statistics Canada. Canada’s increasingly aging population results in tighter labour markets and relatively higher levels of job vacancies. According to the OECD (2019), age is a significant predictor of continuous skill development. Especially when it overlaps with the previous drivers: “older adults are likely to experience significant skills obsolescence, particularly in the context of technological change, unless further training is available to upgrade what they learnt in initial education”.

- COVID-19 Pandemic: The pandemic accelerated and added to some of the challenges associated with the drivers identified above. It brought a significant shift to remote work, new and improved health and safety policies and widespread use of digital collaboration tools. It also highlighted the interconnectedness between countries through global value chains. The pandemic has brought into sharp focus many of the challenges facing underrepresented groups. Job markets are evolving, which has led to a surge in demand for many new skills.

Evidence gathered in key informant interviews indicates that external stakeholders unanimously acknowledged an ongoing need to fund innovative projects and generate research related to the future of work. The most pressing needs identified by interviewees were:

- mobilizing knowledge, such as scaling up projects

- fostering lifelong learning among those in the workforce because of continuous changes or transitions in the labour market

- designing training programs that help workers quickly master new skills and gain competencies

- researching megatrends, structural changes in the global economy

Most of these pressing needs predate the implementation of the Future Skills program but are still present in the Canadian skills development ecosystem. Relatedly, the Labour Market Information Council (2022) recently identified “8 persistent challenges” to Labour Market Information (LMI):

- a lack of local and granular LMI data

- the most frequently used LMI-gathering techniques are rooted in traditional methods, to the exclusion of innovation

- there is no commonly agreed-upon methodology for projecting future skills

- LMI data is often inaccessible, unreliable or not relevant to stakeholder needs

- the needs of end-users aren't being met by most current LMI tools

- the overall impact of LMI tools isn't being tracked

- we lack data that represents a diversity of population groups

- the private sector is innovating, but their data are challenging to validate

Finding 2. Canada’s skills development ecosystem continues to face ongoing challenges in the area of job-related training and labour market information.

Challenges resulting from the rapidly evolving skills requirements are compounded by the barriers Canadians face in accessing labour market information, skills training, and jobs. Some of the most common barriers identified in the two-year review and the literature review include:

- Limited employer-sponsored training makes it difficult for workers to adapt to changing conditions : Canada lags behind other countries in terms of the incidence and number of hours of employer sponsored training. Small and medium-sized enterprises are significantly less likely than larger employers to invest in employee training. The rise of the “gig” economy means that an increasing number of Canadians will find employment through independent contract work and won't have access to traditional employer-led training. Also, there are inherent inequities in employer-sponsored training, as better educated/skilled employees are more likely to receive training than those with lower levels of education. Moreover, only 46% of working-age Canadians take part in job-related training at all. Also, 31% say they want to participate in training but are facing barriers. Main barriers include insufficient time due to work or family commitments, high training cost, or lack of employer support.

- Shortfalls in essential skills required by employers : The Future Skills Council report (2020) stated that “Employers also tell us they need workers with foundational skills such as communication, teamwork, critical thinking, creativity and problem-solving in occupations across all sectors of the economy. They see these skills as integral for productivity and well-functioning workplaces. There is also increasing recognition that social and emotional skills will be important in workplaces being reshaped by new technologies and tools. While some call these “soft skills”, the Council indicated that they see these skills as durable skills that are central to helping people pivot, transition and succeed from one opportunity to the next, even if they are among the hardest skills to develop proficiency in. Labour market information needs to develop consistent, evidence-based, measurable definitions for the various transferable skills.

- Decentralized labour market information creates barriers to matching job seekers with employers : Canada has a lot of labour market information, but the data is fragmented, often hard to access and has many gaps. Information gaps include developments in the workplace, the balance of labour demand and supply in local markets, and the longer-term experience of college and university graduates in the labour market. Provincial and territorial governments collect a wealth of data for their regions, but its sensitivity and a lack of standardization in sampling and terminology make it difficult to use at the national level.

These barriers predate the implementation of the Future Skills program but are still present in the Canadian skills development ecosystem. As presented in the previous section, the Labour Market Information Council report also identified similar barriers.

Finding 3. Underrepresented and underserved groups in the labour market face more barriers.

The labour market changes and the barriers to skills training and information disproportionately affect those who are underrepresented and disadvantaged by the labour market. Research suggests that Canada’s current skills ecosystem isn't well-equipped to address these challenges. Canada Beyond 150 noted in its Future of Work Report (2017) that “the Government of Canada has articulated the importance of addressing pressures of globalization, digital transition, and protectionism by focusing on socio-economic inclusion”.

In a 2021 report, the Social Research and Demonstration Corporation (SRDC) noted that “groups underrepresented in Canada’s labour market include women, youth, Indigenous persons, newcomers, racialized groups, people who identify as 2SLGBTQI+, and persons with disabilities. These groups also tend to be among the least well served by training and employment programs”. While anyone can face a range of barriers to skills development and employment, research highlights “many systemic barriers faced by equity-seeking groups, regardless of skill level”. Employment rates and labour market participation rates are lower for these groups.

For example, the two-year review found that despite progress, Indigenous peoples don't enjoy the full benefits of Canada’s economy. The gap endures between Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous people with respect to many outcomes such as employment, education and housing. Besides, certain jobs have a marked predominance by gender. For example, women disproportionately hold the service sector and administrative jobs, such as cashiers and clerical, that are now being automated at a rapid pace. Men still hold a disproportionate share of skilled trade occupations, which are both well paid and expected to be in demand well into the foreseeable future.

Additionally, a lack of disaggregated data exists to understand the diverse experiences and needs of different equity-seeking groups in Canada. There are some existing programs and initiatives targeted toward underrepresented groups in Canada (such as the Accessible Canada Grants and the Indigenous Skills and Employment Training Program). But as noted by SRDC, “with some exceptions, most national datasets lack appropriate identifiers to capture diverse identities. Data gaps are particularly pronounced for specific equity-seeking groups such as bisexual, trans and gender minority individuals, and about intersections with other identities such as Two-Spirit. Available sample sizes typically don't allow for stratified analyses, deepening inequities”. Furthermore, according to SRDC, there is a “lack of data on the specific experiences of equity-seeking groups [which] serves as a key barrier to designing programs and interventions to address inequities”.

For the Brookfield Institute for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (2017), the uneven labour market representation across different socio-demographics “underlines the need for thoughtful, tailored solutions that are designed in close collaboration with the populations they are intending to support, to ensure that youth from all backgrounds are afforded equal opportunities in Canada’s dynamic, growing tech economy”. For example, recent census data shows that almost one quarter of youth aged 20 to 24 were members of a visible minority. The unemployment rate for this group was 17.2% compared to 14.1% for their white counterparts. The unemployment rate for Indigenous youth in this age category was 22.6%.

Finding 4. The Future Skills Program complements existing programs and initiatives. Ongoing effort is being made to continue to avoid duplication.

The skills ecosystem in Canada includes multiple programs and initiatives to support education, training, and skills development for Canadian workers. However, within the existing system some ongoing gaps need to be addressed to ensure that Canadian workers and employers are provided with the information and training needed to succeed in the evolving labour market.

In 2020, the Future Skills Council released its report about knowledge gaps in the skills development ecosystem in Canada. The report recognizes that business, labour, education and training providers, Indigenous and not-for-profit organizations, and governments need to collaborate. The report presents 5 priorities that highlight the importance of collaboration and innovation across all sectors to build a skilled, agile workforce that is ready and able to shape the future:

- helping Canadians make informed choices by providing access to relevant, reliable and timely labour market information and tools so that all Canadians can make informed learning and training decisions

- equality of opportunity for lifelong learning by promoting, enabling and supporting learning throughout Canadians’ lives, in particular by removing structural and systemic barriers to participation

- skills development to support Indigenous self-determination by enabling First Nation, Inuit and Métis learning and skills development based on a commitment to reconciliation and self-determination

- new and innovative approaches to skills development and validation by promoting, enabling and validating skills development and training in all their diverse forms

- skills development for sustainable futures by developing a skilled workforce capable of adopting new technologies and business models while ensuring the well-being of communities and society

Despite the existence of multiple research and development projects and programs, ongoing and persistent challenges still exist in the development of labour market information (LMI) in Canada. Through its system-wide collaboration efforts and its focus on innovation and evidence generation, the Program aims to address these ongoing challenges by:

- Focussing on innovation that is evidence-based for the future : existing initiatives are largely reactionary and focus on addressing current labour market challenges. For example, provinces and territories tend to spend more on labour market partnerships to find solutions to existing labour market issues, but spend less on research and innovation to identify “new” ways of solving problems. The Future Skills Program aims to experiment, foster innovation and disseminate knowledge on skills development and is geared towards building a more responsive, adaptable labour market.

- Enabling a national, systemic, comprehensive approach : existing initiatives and programs, even where funding is provided by the federal government, tend to target knowledge development and training supports at a regional or provincial/territorial level. While some benefits are associated with this decentralized approach, it seems that a more national systemic lens is lacking to understand the challenges of the future and how to address those across the country. As a pan-Canadian initiative, the Future Skills Centre aims to “connect ideas and innovations generated across Canada so that workers and employers can succeed in the labour market and local, regional and national economies can thrive”Footnote 1. The Centre aims to “bring together experts bridging supply-and-demand-side perspectives, reflecting the diverse interests and supporting approaches that are both people-centric and employer-informed”Footnote 2.

- Targeting underrepresented groups : despite the number of existing federal programs that target underrepresented groups in Canada (Youth Employment and Skills Strategy, Opportunity Funds for persons with disabilities, Indigenous Skills and Employment Training Program, etc.) there is a need to strengthen disaggregated data to better understand the diverse experiences and needs of these underrepresented groups. The Program contains a specific focus on including underrepresented and disadvantaged groups:

- at least 50% of the Centre’s contribution amount is allocated to address the needs of underrepresented and disadvantaged groups

- up to 20% of the Centre’s contribution amount is allocated to address the needs of youth.

More recently (February 2022), the Labour Market Information Council proposed 6 recommendations to address the 8 challenges for Canada’s LMI Landscape mentioned earlier. Of note, the first 4 are elements that the Future Skill’s Program specifically aims to address:

- collaborate to close gaps in LMI generation

- prioritize innovation in LMI

- develop, endorse, adopt, and advocate for best practices and principles

- convene the ecosystem

- champion open access to data and tools

- develop impact and evaluation frameworks for LMI

Most of the work the Program accomplishes complements existing programs and initiatives in the skills ecosystem. With a program as complex and with a scope of work as large as the Future Skills Program, some duplication is inevitable: some key informants perceived some duplication as being unavoidable.

But all key informants in the two-year review agreed that the work done by the Future Skills Program complements existing programs and initiatives. The most common reasons offered by interviewees to support this view was the Program’s focus on future-based experimentation, innovation, and research.

In addition, evidence shows that the Future Skills Centre actively tries to avoid duplication by bringing together stakeholders across the country. This has allowed for the development of a community of practice, breaking down of silos, and sharing of information/learning beyond what had been done to date. This allows various actors to build-off each other rather than duplicate.

5. Program outcomes

Finding 5. The COVID-19 pandemic presented challenges in the early years of the Program and has resulted in delays in achieving outcomes.

The COVID-19 crisis led to unprecedented economic disruption, uncertainty, and hardship for many Canadians. Some sectors, regions, and populations were hit harder than others. Notably, two-thirds of the record 3 million job losses in March and April 2020 occurred in sales and services occupations — jobs where young people, women, Indigenous, immigrant, and racialized workers were all over-represented.

For the Future Skills Centre, it created both operational challenges for an organization trying to develop as a pan-Canadian entity in a time of no travel and systemic challenges that led to disproportionate effects on specific sectors of the workforce.

Specific challenges included:

- delays in implementing projects: most projects funded by the Centre have experienced delays due to challenges related to the pandemic (13 out of 16 in the first year). Thus, producing results data has also been delayed;

- the Centre promptly shifted its activities' focus by privileging projects aiming at helping employers and workers address the immediate challenges of the pandemic. In particular, it funded 64 innovation projects through a Call for proposals to explore ways in which skills innovation could promote resilience and new ways forward in the face of social and economic shocks like COVID-19. Proposals had to examine new insights and models within or across 3 levels of the skills ecosystem: innovation in support for individuals, innovation in support for organizations, and systems change; and

- adapting to using virtual technology to continue efforts to set up a pan-Canadian approach to innovation in the skills ecosystem during a period of restricted travel.

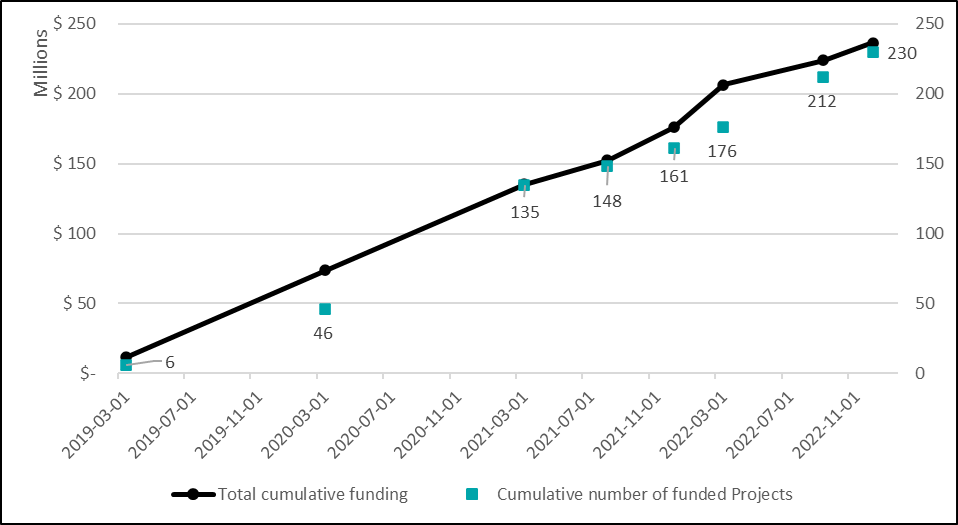

Moreover, the pandemic also impacted the pace for Future Skills Centre Call for proposals and implementing the subsequent selected projects. Figure 1 shows the evolution in the number of funded projects with 95 projects out of 230 approved after March 1, 2021.

Text description of Figure 1

"The figure shows the evolution of the number of projects funded by the program between 2019 and 2023, which increased from 6 (March 1, 2019) to 46 (March 31, 2020), 135 (March 31, 2021), 176 (March 31, 2022) to reach 230 by December 31, 2022.

The figure also presents the cumulative total of funding allocated to the projects by the program, which went from $11.5 M (March 31, 2019) to $73.6 M (March 31, 2020), $135.4 M (March 31, 2021), $206.4 M (March 31, 2022) and finally $236.7 M as of December 31, 2022."

- Source: Future Skills Centre, extracted from 17 different Quarterly activity reports.

Finding 6. The Program has been effective in engaging a pan-Canadian network of diverse stakeholders and experts across the skills development ecosystem.

The Program developed a pan-Canadian network of diverse stakeholders to enable a national, systemic, comprehensive approach to testing innovation, developing knowledge, and replicating and scaling innovation approaches in the skills ecosystem. Since the Program’s start, both the Council and the Centre have brought together actors from across the skills ecosystem to support Canada’s skills development systems in being future-oriented, evidence-based and equitable.

Role of The Council

The Council included 15 members with diverse technical and sectoral expertise on labour market policy. It was gender-balanced and encompassed social and geographical diversity including First Nations, Métis, and Inuit and official languages representation to ensure consideration of all Canadians' skills needs.

During spring 2019, the Council completed the first milestone in its mandate. It undertook a first round of engagement activities to gather perspectives on emerging skills and workforce trends from about 400 individuals from over 150 organizations nationwide representing the public, private, labour and not-for-profit sectors.

Then, the Council prepared a high-level summary report of recurring themes on opportunities and challenges that surfaced across a broad spectrum of partners and stakeholders. This supported the Council in ensuring it was addressing issues of cross-cutting importance to Canadians while being considerate of diversity, regional differences and inclusivity.

Role of the Centre

The Contribution Agreement between ESDC and the Centre requires the latter to develop a pan-Canadian network of partners and stakeholders. The Centre is national in scope and its focus is the entire skills ecosystem. It has made significant progress in building partnerships across the ecosystem with diverse stakeholders in its first 4 years.

Efforts to develop a pan-Canadian network created an effective foundation to enable innovation in the ecosystem. Indeed, most key informants indicated that the Centre is promoting innovation and collaboration in the skills ecosystem beyond what is usually possible, at least to some extent. Most key informants agreed that by connecting various players across the ecosystem, the Centre has facilitated communication, the flow of resources, and the sharing of peer-to-peer learning. According to key informants, this kind of knowledge-sharing helps stimulate innovation.

Most internal and external interviewees agreed that the level of stakeholder engagement is enough to support the objectives of the Future Skills program. The Centre was commended for building a pan-Canadian partnership, implementing pilot projects, and disseminating information to the public.

Some interviewees indicated that the Centre has done a very good job building relationships with provincial and territorial governments. They believed that:

- the consultation has prevented replication and duplication, and

- the federal government on its own may not have been able to achieve the same outcome due to potential concern about jurisdiction.

They also indicated that the Centre brings together stakeholders that traditionally don't. For example, the Centre brought together to deal with sectoral issues, stakeholder groups within one sector (agriculture) that typically have not come under one umbrella.

The Centre has undertaken a variety of activities to engage across the ecosystem, including:

- the Regional Sounding Tour (October 2019 to March 2020) which engaged over 1,032 participants to discuss regional skills priorities, important skills for career success, how to better support vulnerable populations, and a vision for a better skills' ecosystem

- the Virtual Sounding Tour (December 2020 to March 2021) which involved 344 participants to discuss how the pandemic changed program priorities; current labour market challenges; and examples or suggestions for initiatives to address these challenges

- the Centre’s Community of Practice, operated by Magnet, cultivates a pan-Canadian community to foster learning and the shared goal of strengthening Canada’s labour market for the future. As of December 31, 2022, there were a total of 1,577 Collaborator accounts. Since April 2021, there has always been about a third of all Collaborator accounts that have accessed the Community Forum (between 34% and 38%).

To apply a pan-Canadian approach to its work while reflecting the diverse contexts and needs across different regions in Canada, the Centre funded projects in every province and territory, as well as 90 projects that are considered pan-Canadian.

By the end of 2022, the 230 projects representing more than $236M invested show that Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta, and Nova Scotia received the largest shares of funding.

| Province/ Territory | Number of projects | Millions of dollars invested |

|---|---|---|

| Pan-Canada | 90 | 62 |

| Ontario | 72 | 89.7 |

| British Columbia | 46 | 72.1 |

| Alberta | 37 | 57.3 |

| Nova Scotia | 36 | 62.5 |

| New Brunswick | 22 | 27.5 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 22 | 31.7 |

| Manitoba | 21 | 23.7 |

| Québec | 16 | 46.4 |

| Saskatchewan | 14 | 24.7 |

| Prince Edward Island | 13 | 17.8 |

| Yukon | 12 | 6.3 |

| Nunavut | 6 | 5 |

| Northwest Territories | 5 | 3.4 |

- Note : Multiple projects have been implemented in multiple provinces and territories, so total number and value of investments shown in the table is larger than actual.

- Source: Future Skills Centre, "KPI Framework and Performance Update", January 31, 2023

The Centre has set up diverse themes or streams (19 different funding rounds) through which organizations can apply for funding to test innovative approaches to skills development. As of December 31, 2022, over $236M were invested in a total of 230 projects, as shown in Table 4.

| Funding round title | Funding ($) | Funding (%) | Number of projects | % of projects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shock-proofing the Future of Work | 32,930,644 | 13.9% | 63 | 27.4% |

| Scaling | 31,405,679 | 13.3% | 11 | 4.8% |

| Targeted Call 2021 | 31,220,079 | 13.2% | 13 | 5.7% |

| Innovation and Evidence | 27,698,366 | 11.7% | 21 | 9.1% |

| Sector Based | 25,057,312 | 10.6% | 12 | 5.2% |

| Flagship Initiatives | 21,617,241 | 9.1% | 2 | 0.9% |

| Research Project | 14,411,204 | 6.1% | 37 | 16.1% |

| Inaugural | 11,580,437 | 4.9% | 6 | 2.6% |

| Strategic Initiatives | 7,359,314 | 3.1% | 4 | 1.7% |

| Support for Mid-Career Workers | 7,295,394 | 3.1% | 9 | 3.9% |

| Northern Strategy | 6,665,987 | 2.8% | 8 | 3.5% |

| Responsive Career Pathways (RCP) | 5,111,683 | 2.2% | 2 | 0.9% |

| Strategic Initiatives - Research | 4,934,744 | 2.1% | 3 | 1.3% |

| Practitioner Data | 3,161,108 | 1.3% | 10 | 4.3% |

| Sector Based - Research | 2,490,165 | 1.1% | 2 | 0.9% |

| Quality of Work - Research | 1,924,929 | 0.8% | 20 | 8.7% |

| Innovation Lab | 1,188,982 | 0.5% | 4 | 1.7% |

| Opportunext | 440,795 | 0.2% | 2 | 0.9% |

| Research Project - quarterly funding model | 205,000 | 0.1% | 1 | 0.4% |

| Grand TOTAL | 236,699,063 | 100% | 230 | 100% |

- Source: Future Skills Centre, Quarterly Activity Report, December 31, 2022

The Centre has also shown efforts to select projects and distribute funding amongst various sectors in the skills development ecosystem. Table 8 (which includes the most recent data available by sector) shows that the Centre distributed funds across all sectors, with the highest proportion going to universities (16.8%) and non-profit organizations (14.9%).

| Sector | Total Funds ($) | % of total funds | # projects | % of projects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| University | 34,670,420 | 16.8% | 41 | 23.2% |

| Non Profit | 30,749,291 | 14.9% | 16 | 9.0% |

| Public | 21,075,287 | 10.2% | 2 | 1.1% |

| College | 19,641,924 | 9.5% | 15 | 8.5% |

| Private | 7,878,180 | 3.8% | 4 | 2.3% |

| Other | 7,324,190 | 3.5% | 7 | 4.0% |

| No mention | 85,012,217 | 41.2% | 92 | 52.0% |

- Source: Future Skills Centre, Quarterly Activity report, June 30, 2022

- Note: In year 5 (2022-2023), the Centre changed its information reporting format for quarterly activity reports and this is the last information available by sector, based on 177 funded projects at that time.

Finding 7. The Program is setting the stage for innovation in the skills ecosystem. But the extent to which it is experimenting with innovative approaches is unclear and too early to assess.

Overall, assessing the effectiveness of the Program in testing and experimenting with innovative approaches was challenging. Evidence indicates that the Program, largely through the activities of the Centre, has encouraged a new level of innovation in the skills' ecosystem through both its collaborative efforts and its funding to third-party projects that focus on testing the following 3 different types of innovation:

- Core innovation: focuses on incremental iterations on proven models to improve the experiences and outcomes of people accessing existing skills training and development programs. These projects are expected to use existing knowledge, infrastructure and resources to improve and scale proven solutions for increasingly larger numbers of people.

- Adjacent innovation: focuses on adaptations of proven skills development models, applied in new ways and for new needs, and sometimes for new markets. These projects are expected to strengthen the ecosystem’s ability to adapt proven models in new ways and in response to emerging opportunities and threats.

- Disruptive innovation: focuses on brand-new ideas aiming to make breakthroughs and invent skills development models for markets that are nascent or that don't exist yet, and which have the potential to make existing approaches obsolete. These projects are expected to foster truly new and nascent ideas, with the potential to replace current practices, ways of thinking or value systems.

But according to the key informants interviewed, the extent to which these efforts are resulting in approaches that are ‘truly’ innovative is unclear. Thus, it's too early to provide a comprehensive assessment of the evidence generated and the nature of the innovations. Key informants also suggested that lately, more emphasis is placed on supporting projects that are testing innovative approaches.

Some interviewees felt the support for testing innovative projects was limited and not yet exploited to its full potential because of risk aversion. Some key informants expressed the opinion that the Centre is acting too much like a traditional government-funding program designed to safely invest to showcase successes instead of selecting riskier projects which might have a greater chance of failure. Most of these interviewees felt that the Centre has the potential to promote innovation and collaboration in the skills ecosystem beyond what is typically possible, but has not yet fully achieved this potential.

As shown in Table 9, the majority (55%) of funded projects pursue core innovations which focus on incremental iterations with existing resources. Very few (6%) projects target disruptive innovations which seems to be more in line with key informants’ opinions of what is ‘true’ innovation.

| Innovation ambition | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation Horizon | Core Innovation | Core Innovation (%) | Adjacent Innovation | Adjacent Innovation (%) | Disruptive Innovation | Disruptive Innovation (%) | Total | Total (%) |

| Delivery and Iteration | 45 | 19% | 32 | 13% | 2 | 1% | 79 | 33% |

| Research, design, prototype | 38 | 16% | 27 | 11% | 6 | 3% | 71 | 30% |

| Scaling | 26 | 11% | 13 | 5% | 1 | 0% | 40 | 17% |

| Concept Generation | 11 | 5% | 6 | 3% | 3 | 1% | 20 | 8% |

| Systems change | 6 | 3% | 10 | 4% | 2 | 1% | 18 | 8% |

| Needs Assessment | 6 | 3% | 5 | 2% | 0 | 0% | 11 | 5% |

| Total | 132 | 55% | 93 | 39% | 14 | 6% | 239 | 100% |

- Source: Future Skills Centre, "KPI Framework and Performance Update", January 31, 2023

Key informants who felt that the Centre has not yet reached its potential in driving innovation provided 2 main reasons as to why they believe this:

- The program relies too much on funding safe projects that are likely to succeed when it needs to support more projects that are risky and might fail. It was observed that failure is a key part of experimentation and is very important when the focus is on innovation. What didn't work is as important to know as what did work

- Testing of innovative approaches has only been accomplished to a limited extent because most calls for proposals were not designed as test per se (for example, no hypothesis being tested). In this regard, a 2020 OECD review of Future Skills recommended that the Centre should set up quality standards for evaluations to improve the impact evaluation culture in Canada, possibly following the Maryland Scientific Methods Scale.

Finding 8. Early results indicate that there was knowledge developed for the skills ecosystem. But there isn't enough evidence to provide a reliable assessment of the usefulness of the knowledge produced.

Review of administrative documents shows that the work undertaken since 2018 by the Future Skills Centre and ESDC has contributed to addressing the gaps of information available in the skills development ecosystem by:

- making skills development and LMI data more accessible,

- increasing information on a diversity of population groups and especially underrepresented groups in the labour market, and

- fostering exchange of LMI amongst the labour market stakeholders.

As of March 31, 2023, the Centre has produced 120 publications focused on skills innovation, workforce development and labour market issues. These reports are accessible via a searchable database, cover the impact of automation, sustainable livelihoods, career pathways, in-demand skills, and take a skills perspective on labour market information. Also, the Future Skills website proposes a searchable database of innovation projects (by keyword, theme or region) with 128 projects listed and an interactive map (also searchable by target population, sector, skills type or project type) currently presenting only 110 projects.

There is no evidence in reviewed documents or administrative data as to the extent to which these tools are used by skills development partners or Canadians.

External interviewees agreed products were useful to at least some extent in terms of providing insights into emerging skills relevant to Canada’s future economy and labour market. But it was more difficult for external interviewees to identify ways in which products or activities have been useful in providing evidence on valuable training solutions relevant to Canada’s future economy and labour market.

A few interviewees indicated that there needs to be more focus on what does not work and what is a failure when it comes to disseminating evidence. They felt that learning from what does not work is part of research and development. The literature reviewed also refers to the importance of learning from failures to support innovation.

Leveraging from promising early results of its various projects and activities, the Centre has established a plan to ensure that information gathered from its funded projects results in valuable insights to the ecosystem. The Future Skills Centre is developing a comprehensive compendium of evidence from each project to carry this out.

Given the limited number of completed projects to date, the knowledge generated or its usefulness can't really be assessed yet.

Finding 9. The Program has undertaken a variety of knowledge mobilization activities to help inform and influence skills-related policies and programs. But impacts of these efforts on policies and programs aren't clear yet.

Both the Future Skills Centre and ESDC play a role in the knowledge mobilization on the skills of the future and on influencing policies and programs. It's too early to assess any impact related to knowledge dissemination and influence on policies and programs given the limited number of completed projects. But early results show progress in this area. Most interviewees assessed the Program’s ability to disseminate evidence in a positive way.

Some interviewees, largely external, felt results have been limited so far and raised the following points:

- While the program has many accessible reports and bulletins, there isn't enough yet to actually tell "what works" and why, or “is it replicable?”

- While evidence is growing, much of the data coming out still needs to be analysed. Clear evidence about what works, and lessons learned will take more time as there isn't enough evidence yet in the scaling portfolio.

Review of available administrative documents provides an overview of ESDC's knowledge mobilization activities:

- Knowledge Blast - curated content (including evidence, insights, and information) about Future Skills Centre research, projects, and knowledge dissemination events that is relevant to the work of various government audiences. The Knowledge Blast goes out to 140 recipients per month across ESDC and other federal government departments (including Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Canada Border Services Agency, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Environment and Climate Change Canada).

- ESDC Skills and Employment Branch Talks— a learning series that promotes discussion, collaboration, and knowledge transfer within the Branch. These talks are promoted to working level and senior management staff. Since September 2021, 5 widely-attended talks were hosted that covered the following topics:

- insights and evidence generated from Future Skills implemented projects,

- how they have scaled-up promising projects,

- their relationships with provinces and territories,

- thematic findings on digital platforms, and

- engaging Northern communities in Canada.

- Forum for Labour Market Ministers – the Centre has been engaging with a designated task team to explore opportunities to collaborate on either new or existing projects. ESDC facilitated this engagement opportunity between the task team and the Centre.

- Assistant Deputy Minister Interdepartmental Committee on Jobs, Skills and Training – this Committee was originally created to help outline the role and mandate of the Future Skills Centre. Fifteen (15) federal departments are currently participating. The ongoing objectives of the Committee are to engage in a discussion on:

- how the Centre can support federal departments and stakeholders address anticipated workforce development issues

- the Centre’s Strategic Initiatives Fund

- Director General Interdepartmental Table on Jobs, Skills and Training - to support horizontal collaboration and information sharing on workforce development issues. It's chaired by Skills Employment Branch and includes fifteen (15) federal departments.

- Other Government Department Engagement –ongoing information exchanged, engagement and meetings held to inform higher level tables.

While documents reviewed show that ESDC undertakes a variety of activities to help mobilize knowledge, most key informants, both internal and external, felt the work to date in this area has been limited. The review also suggests that in the implementation of the Future Skills initiative, external engagement and communications activities were mainly carried out by the Future Skills Centre. Only a few internal key informants were aware of ESDC’s knowledge mobilization actions. The following challenges were expressed:

- ESDC limited direct contact with provinces and territories while the Future Skills Centre has relationships with these governments

- Insufficient evidence to mobilize knowledge generated to influence government policies and programs

- ESDC needs to increase its visibility to ease information-sharing. Scaling up/knowledge mobilization will likely require some facilitation through government partnerships.

On the other hand, the Future Skills Centre created structures, platforms and relationships to disseminate information and also made significant investments in this regard.

A 28.2 millions of dollars project was funded to develop and support Future Skills Centre’s digital infrastructure platform, undertake knowledge dissemination and mobilization activities, support the development and maintenance of the Future Skills Centre website and facilitate a Community of Practice platform. The platform aims to cultivate a pan-Canadian community in order to foster learning and the shared goal of strengthening Canada’s labour market for the future.

Most interviewees assessed evidence dissemination in a positive way. Reasons given were mostly related to activities and products, including the Future Skills Centre visibility and promotion of newsletters, reports, webinars, podcasts, and speaking engagements.

While the evidence shows a promising start to the Centre’s knowledge mobilization efforts, a few interviewees from the two-year review felt that there should be greater sharing of results and best practices to enable innovation project proponents to learn more from other innovation projects including their challenges and successes.

The two-year review also found that in most areas assessed the reach of the Centre’s knowledge mobilization activities had increased. Review of available data since then has confirmed this with a constant increase in website visits, social media followers (Twitter, LinkedIn, and Instagram), as well as distinct reports downloads.

Finding 10. As per the Program objective, most funded projects focus on underrepresented, disadvantaged and equity-deserving groups. But it's too early to assess the impacts on these groups.

The Program includes a specific focus on including underrepresented and disadvantaged groups so all Canadians can benefit from emerging opportunities. But the evidence on results of these approaches and outcomes for these groups is still very limited.

The Contribution Agreement with the Future Skills Centre stipulates that at least 70% of the funding must address the needs of disadvantaged and underrepresented groups with at least 50% of the Centre’s contribution amount to address the needs of underrepresented and disadvantaged groups, and up to 20% of the Centre’s contribution amount to address the needs of youth.

The Centre has exceeded this requirement by attributing 63% ($148,378,217.59 out of $236,699,063) of its funding to projects that target these groups. This accounts for 73% (168/230) of funded projects.

| Underrepresented and Equity-seeking group | Number of projects | % of all projects (230) |

|---|---|---|

| Women | 67 | 29.1% |

| Indigenous | 61 | 26.5% |

| Youth | 58 | 25.2% |

| Racialized | 51 | 22.2% |

| Newcomers | 44 | 19.1% |

| Rural/Remote/Northern | 40 | 17.4% |

| Disability/Deaf | 31 | 13.5% |

| Immigrants | 22 | 9.6% |

| 2SLGBTQI+ Persons | 17 | 7.4% |

| Other | 17 | 7.4% |

| People with essential skills gaps | 16 | 7.0% |

| Language/Minority | 15 | 6.5% |

| People without Post-Secondary Education | 9 | 3.9% |

| None | 34 | 14.8% |

| No answer/Empty | 31 | 13.5% |

- Note: Many projects focus on more than one underrepresented group, so totals add up to more than 230 projects and 100%.

- Source: Future Skills Centre, Quarterly Activity Report, December 31, 2022

Key informants identified some approaches that facilitated the targeted focus through implementation of:

- an evaluation process for project applications with a focus on how they will address the needs of equity-deserving groups

- a funding stream dedicated to supporting skills development for equity-deserving groups

- a 50/30 challenge – a commitment that 50% of leadership in projects is female and 30% racialized

- a Centre’s advisory board that reflects equity-deserving groups in its membership and holds itself to the same standards for diversity and inclusion as those applied to the funding project applications assessment

- the Facilitating Access to Skilled Talent (FAST) program for newcomers by the Immigrant Employment Council of BC

- a network or community of practice, such as bringing together individuals and organizations that deal with members of equity-deserving groups.

A few interviewees emphasized that more could be done to reach groups in the North, including focusing on particularly significant issues for the North in general and the Inuit. The Future Skills Centre has started to act on this aspect with its Northern Strategy that is currently being developed.

Other specific groups identified as challenging to reach were:

- persons with disabilities

- Veterans