Pandemic Agreement Regional Engagement Series: Summary Report

Download in PDF format

(1,925 KB, 54 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: 2024-07-24

Cat.: HP55-10/2024E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-72379-2

Pub.: 240272

Table of contents

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Background

- Overview

- Attendees

- Article-specific input

- Other concerns

- Cross-cutting issues

- Conclusion

- Annex A: Winnipeg (English, in-person)

- Annex B: Montreal (French, hybrid)

- Annex C: Online 1 (English, virtual)

- Annex D: Halifax (English, in-person)

- Annex E: Online 2 (English, virtual)

- Annex F: Vancouver (English, in-person)

- Annex G: Whitehorse (English, hybrid)

- Annex H: Toronto (English, in-person)

Executive summary

From January 29 to February 12, 2024, the Office of International Affairs for the Health Portfolio held the Pandemic Agreement Regional Engagement Series. The engagements were an opportunity to gather partner and stakeholder input on the negotiating text of the World Health Organization (WHO) Pandemic Agreement. The engagement sessions were held in Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver, Whitehorse and Winnipeg using a combination of in-person, virtual and hybrid formats, with a total of 75 individuals attending in person and 41 attending online. Representation spanned diverse sectors, including provincial and territorial governments, Indigenous organizations, academia, public and private sectors, civil society, and associations.

This report summarizes what the Office of International Affairs heard from partners and stakeholders during the engagement sessions. It is important to note that the views articulated in this report are those of the participants, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of Canada.

Canada, as a WHO Member State, has actively participated in the development of the Pandemic Agreement, recognizing the necessity of a robust global health security architecture. Canada's engagement strategy adopts a whole-of-government, whole-of-society approach, aiming to include perspectives from Provinces and Territories, Indigenous organizations, academia, civil society, private sector, and youth.

The sessions began with opening prayers by local Elders, followed by a presentation on the development of the Pandemic Agreement and Canada's negotiation priorities. Attendees identified articles of relevance to their organizations and provided input on practicality,the ability to implement, and potential challenges during implementation.

Overview of article-specific input

Article 4: Pandemic prevention and public health surveillance: Comprehensive prevention strategies, inclusive surveillance practices, and addressing challenges for marginalized communities are essential for effective pandemic prevention.

Article 5: One Health: Recognizing the role of climate change, emphasizing animal-related factors, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, and ensuring equity are crucial aspects of the One Health approach.

Article 6: Preparedness, readiness and resilience: Prioritizing equity and community well-being, strengthening public health systems, minimizing negative impacts, and addressing implementation challenges are key elements for effective preparedness and resilience.

Article 7: Health and care workforce: Ensuring equity, expanding the scope of the workforce, and addressing capacity and sustainability challenges are vital for supporting the health and care workforce.

Article 8: Preparedness monitoring and functional reviews: Harmonizing reporting standards and engaging diverse non-government organizations (NGOs) are critical for effective monitoring and evaluation.

Article 9: Research and development: Building capacity, promoting information sharing, fostering equity and collaboration, and balancing public and private interests are essential for advancing research and development in pandemic preparedness.

Article 10: Sustainable production: Recognizing regional disparities, promoting sustainable usage practices, defining the roles of member states, and ensuring implementation and accountability are crucial for the equitable and sustainable production of pandemic products.

Article 11: Technology transfer and know-how: Balancing public and private interests, ensuring consequences for technology transfer failures, and maintaining incentives for innovation are essential for effective pandemic response.

Article 12: Access and benefit sharing: Balancing public and private interests, addressing implementation challenges, and ensuring transparent and equitable access to pandemic products are critical for global health equity.

Article 13: Global supply chain and logistics network: Prioritizing equitable access, strengthening supply chains, and diversifying suppliers are essential for ensuring effective global distribution and access.

Article 14: Regulatory strengthening: Harmonizing regulations, streamlining approval processes, and facilitating international regulatory assessments may help accelerate approvals during pandemics.

Article 15: Compensation and liability management: Balancing public and private interests, strengthening indemnification clauses, and ensuring accountability are vital for fair compensation and liability management.

Article 16: International collaboration and cooperation: Addressing implementation challenges, defining private sector obligations, and ensuring enforceability of the Agreement are essential for effective international collaboration.

Article 17: Whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches: Defining meaningful engagement, recognizing unique Indigenous considerations, and exploring alternative models are important for comprehensive pandemic response strategies.

Article 18: Communication and public awareness: Countering misinformation, promoting equity and inclusivity, ensuring transparency, and building health literacy are essential for effective communication and public awareness.

Article 19: Implementation capacities and support: Allowing countries to determine their own capacities, developing a baseline of responsibilities applicable to all nations, and establishing further obligations based on individual national capacities will help to ensure an equitable and effective pandemic response.

Article 20: Financing: Addressing governance and equity issues, establishing sustainable funding mechanisms, and championing equity goals are essential for financing pandemic response efforts.

Feedback was received regarding the need for greater clarity, and strengthened language relating to enforceability and human rights within the draft Agreement. Attendees stressed the importance of interdisciplinary approaches, equity, and capacity building to address disparities and promote sustainability.

Cross-cutting issues highlighted equity, human rights, capacity building, international collaboration, transparency, and sustainability as crucial considerations. Balancing public and private interests, ensuring access to pandemic products, and addressing challenges faced by Indigenous and marginalized communities were also emphasized.

Participants recommended that, moving forward, the Agreement would greatly benefit from clearer mechanisms for enforcement, more transparency, and stronger wording regarding equitable collaboration to effectively address global health challenges and strengthen pandemic preparedness and response efforts.

Introduction

From January 29 to February 12, 2024, the Office of International Affairs for the Health Portfolio held the Pandemic Agreement Regional Engagement Series. The Engagement Series was an opportunity to gather partner and stakeholder input on the negotiating text of the WHO Pandemic Agreement. The engagement sessions were held in Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver, Whitehorse and Winnipeg using a combination of in-person, virtual and hybrid formats, with a total of 75 individuals attending in person and 41 attending online.

This report summarizes what the Office of International Affairs heard from partners and stakeholders during the engagement sessions. It is important to note that the views articulated in this report are those of the participants, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of Canada.

Background

In December 2021, the 194 WHO Member States, including Canada, agreed to launch an intergovernmental negotiating body (INB) to develop a new WHO convention, agreement or other international instrument on pandemic prevention, preparedness and response (a "Pandemic Agreement"). Member States subsequently agreed to develop the instrument as legally binding under the WHO Constitution, further signifying their commitment to strengthening PPPR. Negotiations of a draft text started in early 2023 with the text of the Agreement evolving through multiple iterations. The development of a new Pandemic Agreement is expected to conclude in 2024. Canada has been supportive of this process, as a stronger and better coordinated global health security architecture for disease outbreaks is essential to securing the health and safety of Canadians in a globalized world.

Canada is taking a whole-of-government, whole-of-society approach in the development of the Agreement to ensure that Canadian priorities and values are reflected. Canada's partner and stakeholder engagement strategy aims to facilitate meaningful and inclusive engagement from Provinces and Territories, Indigenous organizations, academics and experts, civil society organizations, private sector, and youth.

Following the release of the zero draft, the Office of International Affairs for the Health Portfolio hosted the Pandemic Instrument Partner and Stakeholder Engagement Forum (March 2023) to facilitate conversations with Canadian partners and stakeholders on thematic issues in the Pandemic Agreement. Forum participants stressed the importance of continuing the consultation process and promoting a greater diversity of voices. As a result, following the release of the negotiating text, the Office of International Affairs for the Health Portfolio held the Pandemic Agreement Regional Engagement Series in 6 locations across Canada and online.

Overview

Each session commenced with an opening prayer by a local Elder followed by a presentation from the Team Lead or Chief Negotiator. The presentation provided an overview of progress to date on the development of the WHO Pandemic Agreement, including how the decision came about to develop an agreement, the negotiating dynamics, Canada's priorities and objectives in participating in negotiations and its engagement strategy. The presenter explained that the Regional Engagement Series was an opportunity for partners and stakeholders to inform the negotiating team so they can best represent Canadian interests in the ongoing development of the Pandemic Agreement.

Guided by an external facilitator, attendees identified the articles in the Agreement of the greatest relevance to their organizations and for which they most wanted to provide information to Canada's negotiating team. They then had the opportunity to provide input on the selected articles from the perspective of their stakeholder group or populations they represent, focusing on the practicality, the ability to implement, and feasibility of measures. Depending on the number of participants in the session, attendees offered their input either in the full group or in break-out groups. Prompting questions included:

- Are there specific challenges for implementation at the community level?

- Are there any aspects of the provisions that could be considered impractical or overly burdensome in real-world scenarios?

- Do you anticipate any resistance or challenges from stakeholders during the implementation phase?

- What might the unintended consequences of these provisions be, including on those living in situations of vulnerability?

The discussion was captured by an external notetaker.

Attendees

Meaningful and inclusive engagement is important to Canada in the development of the Pandemic Agreement so that policy decision makers understand the needs, concerns, and perspectives of those that may be impacted by proposed measures and to ensure Canadian values and interests are reflected in any future agreement.

The engagement series took place in a hybrid format, welcoming 75 in-person participants (65%) and an additional 41 online (35%). Attendees represented the following sectors: First Nations, Métis, Inuit organizations (11%); academics, experts and researchers (24%); public sector (14%); private sector (4%); civil society, non-governmental organizations and not-for-profits (23%); associations (9%), and other (15%).

Figure 1: Text description

| Type of organization | Total participants |

|---|---|

| First Nation, Metis, Inuit Organization | 11 |

| Experts and Researchers | 24 |

| Public Sector | 14 |

| Private Sector | 4 |

| Civil Society | 23 |

| Associations | 9 |

| Other | 15 |

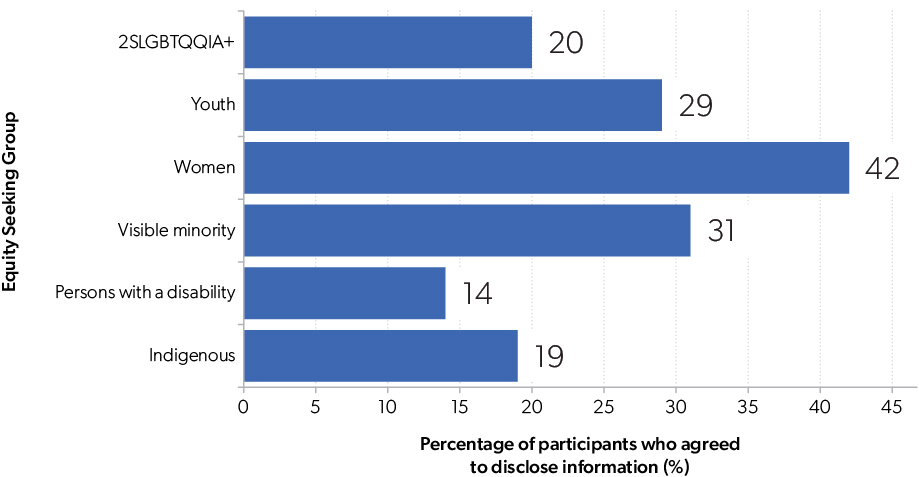

Attendees that agreed to share personal information (n=98) identified as or affiliated with an organization representing the following: Indigenous peoples (19%), persons with disabilities (14%), visible minorities (31%), women (42%), youth (29%), and 2SLGBTQQIA+ communities (20%).

Figure 2: Text description

| Equity seeking group | Percentage of participants who agreed to disclose information (%) |

|---|---|

| Indigenous | 19 |

| Persons with a disability | 14 |

| Visible Minority | 31 |

| Women | 42 |

| Youth | 29 |

| 2SLGBTQQIA+ | 20 |

Article-specific input

Participants provided input on specific articles of their choosing either in a full group setting or in break-out groups, depending on session attendance.

Article 4: Pandemic prevention and public health surveillance

A broad-based approach to prevention

It would be beneficial for the scope of prevention to be broader than what is currently outlined in the article, reflecting the need to develop and implement preventive measures in the wider context of upstream factors that drive outbreaks. Building public trust, enhancing baseline health literacy, and ensuring rapid response at all levels are all essential for effective prevention. Guidance on prevention and control are crucial in healthcare, research and community settings. Water sanitation, indoor air quality and ventilation should be prioritized.

Importance of surveillance and data

Public health surveillance should be interpreted broadly to include targets such as risk factors, behaviours, genomics and wildlife monitoring. Data standards, collection and reporting capacity, and adequate information systems are all critical to effective surveillance and rapid response. Additionally, data ownership, privacy, inclusivity, race-based data and cultural sensitivity are important issues which could be given greater consideration. Citing international best practices, for example data collection/sharing models in use in the United Kingdom, could strengthen this article.

Challenges for Indigenous and remote communities

Indigenous and remote communities face a number of unique challenges in pandemic prevention, exacerbated by issues like inadequate housing and lack of clean water, which contribute to disease spread. Data collection can be a challenge, compounded by strained relationships between Indigenous people and the health system, marked by trust deficits and ingrained power differentials. Meeting the needs of marginalized communities in Canada must be given the same importance as supporting low and middle income countries (LMICs).

Capacity building

Unequal capacities for prevention and surveillance between high income countries (HICs) and LMICs, and within countries as well as across jurisdictions and regions within countries should be recognized and addressed, particularly areas such as biosafety and biosecurity. Increasing resources and laboratory capacity in remote communities, both in Canada and around the world, should be recognized as essential to the effective implementation of infection prevention and control measures.

International cooperation

Making improvement in interoperability would be a significant step toward truly coordinated pandemic prevention and surveillance. International standards and guidelines for data, pathogen detection and biosafety, associated support and expertise for LMICs, and strengthened collaboration among countries, national and regional governments, and academia are needed.

Article 5: One Health

Inclusion of climate change and planetary health

Climate change, environmental health, and planetary health are central to One Health considerations and deserve greater prominence in the article. Climate change should be acknowledged as a driver of zoonotic disease. Additionally, text from earlier drafts of the article that highlighted the top drivers of pandemics, as identified by the United Nations Environment Programme and the International Livestock Research Institute, should be reinserted.

Greater prominence for animal use

The importance of animals to economies should be included in the article. One Health encompasses the relationship between human health, animal health and the environment, including how we use animals in agricultural and through wildlife trade. The impact of animal use on public health, as reflected in the pandemic drivers noted above, underscores the importance of considering animal-related factors in pandemic prevention and response efforts.

Interdisciplinary approaches

One Health is primarily concerned with cross-disciplinary issues. Multisectoral and transdisciplinary collaboration will be essential to break down existing siloes. However, it is often difficult to access funding for the interdisciplinary research that One Health requires. Improving access to funding, possible through targeted funding streams and an appropriately broad understanding of One Health are needed to support this work.

Implementation challenges

Effective implementation of One Health will require appropriate consideration of the varying circumstances, capacities, and contexts among countries and, internal jurisdictions. Establishing standards appropriate to regions and contexts would be helpful, and engagement and collaboration with the agricultural industry are key. Providing more detail in the article regarding decision-making and compliance mechanisms would be beneficial. One possible implementation approach could be setting up a scientific advisory committee to provide recommendations for how to best achieve progress in key areas.

Equity

An inclusive approach should be taken when identifying stakeholder groups, and an equity lens should be applied to account for unintended impacts and consequences for marginalized groups. One Health negotiations would benefit from taking an inclusive approach to identifying and engaging with stakeholder groups, as week as taking Indigenous knowledge and lived experience into account. It is also important to remember that, often countries/groups most crucially needing to be engaged do not have the resources required to fully participate.

Article 6: Preparedness, readiness and resilience

Equity and community building

A large part of preparedness, readiness and resilience lies in the interactions among members of society. Inequities and insecurities within communities should be considered. In urban areas, where people may be less connected to one another, efforts should be made to support the wellness of the community. Resilience is particularly an issue for minority groups, who disproportionately staffed many essential jobs and were put at high risk during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Importance of public health systems

Strong and independent public health systems with amplified voices are essential, particularly during pandemics. It would be worth considering placing more emphasis on protecting the regulatory and legal tools that public health departments can use to implement public health measures quickly based on the best scientific evidence available. Additionally, the importance of ensuring that capacity and institutional memory are retained between crises could be noted.

Minimizing negative impacts of pandemic response

The Agreement should guide efforts to mitigate the negative impacts of require public health protections in other areas of society, such as disruptions to education and the economy. Including clear guidance on which "essential health services" should continue, even during lockdowns and other public health restrictions, as well as member states' baselines for these services, would be useful. Important health services not specified in the text include childcare, mental health supports and palliative care.

Implementation challenges

The exact mechanism for enforcement and implementation of the provisions in Article 6 could be more clearly described. Much of the language is vague, and the provisions do not account for the fact that surveillance challenges exist and standards relating to essential health services will differ between HICs and LMICs. Within Canada, there may be inter-jurisdictional challenges that will need to be addressed to ensure effective and efficient implementation.

Value of lived experience

Article Sic could be improved by more clearly articulating the value of lived experience, including the experience and knowledge of communities with less capacity. Examples like Ebola management and One Health approaches demonstrate that LMICs and Indigenous groups have valuable lived experience that can inform effective strategies.

Long-term impacts

Preparedness efforts must acknowledge that the impacts of a crisis, may extend into the medium and long term. The article could more clearly address long-term health consequences, such as the impacts of long COVID. Longitudinal studies and sustained funding to understand the causes and monitor the consequences at the individual, community and national levels would be beneficial. Related to this, the article could provide detail on strategies for ensuring sustainability during extended pandemic events, as well as facilitating workforce and health system recovery.

Article 7: Health and care workforce

Equity and inclusivity

The article should apply an equity lens throughout but should not be too specific when identifying vulnerable populations to avoid excluding anyone. It should emphasize not only gender and youth, but also race and ethnicity. Furthermore, there should be clearer discussion on fair remuneration, respecting working conditions, and promoting diverse representation in planning processes. To effectively address disparities, action must be taken before health emergencies arise.

Capacity and sustainability

The article should address the development of an effective workforce, building overall capacity and planning for surge capacity. Safeguarding the physical and mental health of health and care workers will be essential to sustain capacity during and between pandemics, along with preserving expertise and institutional memory. The ethical migration and recruitment of healthcare personnel to HICs should be addressed to limit the loss of health human resources in other countries. Implementing flexibility in licensing nationally and internationally could alleviate temporary worker shortages.

A broader scope

The current definition of the health and care workforce is too restrictive. Allied health and support service workers are critical to the functioning of health systems and should be included. Additionally, the article should more broadly address factors that impact the capacity and sustainability of the health and care workforce, including mental health, access to housing and childcare and ensuring equitable pay.

Article 8: Preparedness monitoring and functional reviews

Harmonization and standardization

While countries use different tools for monitoring and evaluation, and many have limited resources to do so, reporting must happen in comparable ways. Standards and systems must be put into place to ensure consistency in reporting and implementation.

Engaging diverse NGOs

NGOs often have important information about what is happening on the ground in a given region. Engaging with NGOs that represent a diversity of issues, regions and constituents will provide valuable input to the peer review process.

Article 9: Research and development

Capacity and sustainability

The sustainability of research infrastructure is important for ensuring that pandemic readiness can be ramped up at any time. This will require investment across jurisdictions to maintain capacity and a skilled research workforce. Establishing equitable and inclusive partnerships will help build capacity in LMICs. Moreover, building and maintaining capacity in areas beyond clinical trials is also important, including behavioural, gain of function, and discovery research, as well as modeling; public health research; preventive countermeasures; and pre-commercial manufacturing. The private sector must be incentivized to build laboratories and research facilities in LMICs as this will improve local economic stability and ensure improved access to medicines, vaccines and knowledge.

Information sharing and knowledge translation

Rapid response to novel threats relies on the rapid sharing of information and the translation of knowledge into practice. Mechanisms and frameworks for disseminating information across the academic, private and government sectors should be developed ahead of time. Furthermore, research knowledge should be translated appropriately for the general public to support transparency and credible crisis communications.

Harmonization and standardization

Internationally coordinated and standardized training programs, regulatory harmonization, and cross-jurisdictional approvals are necessary conditions for achieving the objectives outlined in the article and will help expedite the availability of innovations.

Equity and collaboration

Opportunities should be created for LMICs and Indigenous communities to be part of the research process. Increasing collaboration on clinical trials presents an opportunity to build trusted relationships but will require training and resources to build capacity. Transparency with stakeholders and ensuring diversity among clinical trial subjects will help address vaccine hesitancy.

Balancing public and private interests

The language around technology transfer and licensing is vague and publicly funded research needs clearer definition. Equity in pricing and availability of pandemic products across all countries will be essential. Nevertheless, incentives must be maintained for companies to bring developments to market. Public disclosure requirements may discourage private sector research and delay the development of vaccines and therapies.

Article 10: Sustainable production

It is important to acknowledge equity both between and within countries. Regional gaps in access to and the availability of pandemic products can be addressed by improving production capacity within and across countries. Member states will be producers or users of pandemic response products, or both. These roles could be better defined in the text.

Sustainability

The sustainability of pandemic products should extend to sustainable usage practices. Efficient use, waste reduction, potential for recycling and strategic roll-out planning to avoid expiration of vaccines, etc. are key considerations that should be addressed. Furthermore, the disposal aspect of waste management is a significant issue in the Canadian North, LMICs and other remote communities. It is important that the Agreement reflect these realities.

Implementation and accountability

The article would benefit from stronger language and mechanisms to ensure that companies and countries abide by its provisions and that manufacturers sell pandemic products at affordable prices. Greater clarity would also help regarding the role of private industry, as well as ways to address challenges in developing contracts and ensuring that all parties can and do meet contractual obligations in often rapidly changes situations. There is also an opportunity within this article to help resolve issues relating to transparency of licensing and alignment with existing trade agreements must be resolved. While some countries are pushing for royalty-free licensing, it is acknowledged that royalties are an important incentive for the private sector. Capped or limited royalties may be a better approach.

Article 11: Technology transfer and know-how

Balancing public and private interests

It is noted, in the version of Agreement text reviewed, that legally binding obligations from previous versions have been removed. This may tip the balance too far in favour of private benefit. As mentioned earlier, the private sector must receive benefit for its investments, research, risks taken, intellectual property (IP) and production. However, we must also strongly support technology transfer. More discussion is needed to appropriately balance these considerations, as such a balance is crucial for effective pandemic response.

Article 12: Access and benefit sharing

Balancing public and private interests

The same holds true for balancing private and public interests with respect to access and benefit sharing. Access to medical countermeasures can be a matter of life and death. Providing global access to vaccines and other pandemic response products will shorten pandemics and likely save lives domestically. More discussion through the international negotiating sessions will be crucial in ensuring private sector companies receive appropriate incentives and compensation, while at the same time ensuring the benefits of their output, which are often partially funded by government, are shared globally. Between pandemics, we must drive innovation through the retention of IP, but clarity is needed on how far the protection of IP goes. Canada must stand firm in supporting LMICs. A partnership approach that involves splitting the proceeds with LMICs could provide incentives for everyone involved.

Implementation challenges

Pathogens and IP must be shared to protect health and lives globally, but the issue is complex. The data, information or samples shared may not lead to a specific product or other directly related output. Benefit sharing may require a broader definition in order to incentivize both HICs and LMICs. Determining "affordable" access must be done in a transparent way.

Article 13: Global supply chain and logistics network

Equitable access

Countries clearly have the right and responsibility to procure and hold vaccines, medical supplies, PPE, etc., for their populations. However, this should not tip into protectionism and unnecessary stockpiling that can disadvantage other countries and regions. The article should address barriers to open trade and should include a provision that donated materials are not nearing their expiration date.

Strengthening supply chains

The resilience of supply chains is closely linked to access and benefit sharing. The article should directly address the quality of supply chains. The WHO Model Quality Assurance System (MQAS) could be used as a certification tool to strengthen supply chains.

Diversifying suppliers

Diversification of sourcing and utilization will make systems more resilient and reduce the likelihood of shortages or bottlenecks. Enabling local companies to supply PPE will help bolster local economies and ensure regional access to essential resources.

Article 14: Regulatory strengthening

Harmonization and standardization

Regulatory harmonization is critical to rapid response during a pandemic. Some countries already rely on the regulatory approvals carried out by other countries. International assessments to review products could be an option during pandemics to help expedite approval processes for countries with limited regulatory capacity.

Article 15: Compensation and liability management

Balancing public and private interests

The language around indemnification clauses must be strengthened to ensure the accountabilities, expected benefits, and obligations of the public and private sectors are clearly articulated and appropriately balanced.

Article 16: International collaboration and cooperation

Implementation challenges

It is noted that this article is more aspirational than practical. Should it be made more operational, it will need greater clarity regarding private and public sector obligations, articulating the distribution of responsibilities and enforcement.

Article 17: Whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches

Implementation challenges

More detail is needed in terms of defining "meaningful engagement", including specifying who will be involved in multisectoral mechanisms, and addressing potential conflicts of interest within the private sector. The involvement of civil society groups and other NGOs will result in more effective decision-making; these groups often have important knowledge of what is happening on the ground. It could be argued that Canada does not currently meet the requirement of establishing a national coordinating multisectoral mechanism as defined in this Article, so greater discussion round this is needed.

Applying an equity lens

The social and economic determinants of health, including mental health, should underlie and be fully integrated within whole-of-government approaches. "Equitable restoration" implies returning to pre-pandemic status and levels of support, but lessons learned during the pandemic must be incorporated in recovery efforts to improve healthcare and public health systems for all people.

Recognizing unique Indigenous considerations

Canadian Indigenous governments have jurisdiction over their own people. The article should specify a "whole-of-governments" (plural) approach. Wording used by New Zealand and Australia in relation to their Indigenous populations could serve as a model. To enhance buy-in and build relationships between Indigenous communities and the healthcare system, local physicians and community leaders should be engaged to build trust. This will filter down to community members, facilitating more effective healthcare delivery and engagement.

Alternative models

Is the whole-of-government approach really the most effective strategy for pandemic response? Emergency management is another well-established model that tends to be less politicized than whole-of-government approaches. Emergency management has a similar capacity to broadly access government resources across federal, provincial and territorial levels.

Article 18: Communication and public awareness

The threat of misinformation

Countering misinformation and disinformation is critical to pandemic response efforts, as seen by its impact on vaccination and immunization rates around the world. Providing consistent and trusted messaging from credible sources across communication channels will help to counter the increasing flow of misinformation. Efforts should be made to hold social media platforms accountable for the content they host. However, it is imperative to address misinformation in a manner that respects freedom of speech and expression.

Equity, diversity and inclusivity

Accessibility and inclusivity must be fundamental principles of pandemic communications. Messaging should be tailored to diverse audiences, be culturally informed and translated appropriately. Communication channels should reflect the intended recipient populations/communities, and efforts should be made to incorporate lived experiences and anti-racism messaging to counteract scapegoating. Establishing community partnerships prior to the onset of crises will facilitate more effective outreach to marginalized groups.

Transparency and public trust

Open and transparent public health communication is critical and can be considered a social determinant of health. Trust in public institutions and experts in medical, public health, and emergency response fields must be strengthened. Communication and decision-making processes must be transparent, clear, accurate, consistent and evidence based. Health communication should come from health authorities and experts to minimize politicization of the pandemic response.

Building health and pandemic literacy

Improving general literacy and fundamental science and health education are precursors to improving science and health literacy. Public health and pandemic literacy should be integrated in the K-12 curriculum and should be promoted among global leaders so that decision making and policy are based on science and evidence.

Article 19: Implementation capacities and support

Equity and capacity

Countries should be able to define their own level of capacity as part of international assessments. Establishing a baseline of responsibilities applicable to all countries, with further responsibilities dependent on capacity, could be a solution to the diverging views on the concept of common but differentiated responsibilities.

Article 20: Financing

Governance and equity

Resourcing is a significant issue for small governments which impacts their ability to set priorities. Financing should be addressed for every article in the Agreement. Governance of the financing mechanism should be spelled out to address issues such as the earmarking of funds and to ensure funds are appropriately allocated. Sustainable funding for public health systems should be specified to prevent capacity erosion during inter-pandemic periods. Canada could be a champion for equity goals in this context.

Other concerns

Lack of clarity and detail

As sections of the draft Agreement are vague, there are questions on how it will be implemented and enforced as a legally binding text. Relating to this, greater consistency of terms would be helpful; internationally agreed upon definitions may be warranted for some terms.

Strengthening human rights

The document could be improved by including stronger human rights language throughout. Adding an article that explicitly commits to the respect of human rights and collaboration with LMICs may be the best way to address this. Because public health policy must be based on human rights, adherence to public health measures should be specified across the articles.

Need for interdisciplinary approaches

The Agreement espouses interdisciplinary approaches, but in practice policy and programming tends to be focused on specific, siloed problems. One Health and whole-of-government principles represent an opportunity to bring together many different issues across other international treaties.

Equity and capacity building

Equity and support for addressing lack of capacity should be clearly present throughout the articles. An equity lens should be applied to the assessment of functioning and gaps. Equal representation should be ensured in the engagement process.

Cross-cutting issues

The following are cross-cutting issues that emerged from the Pandemic Regional Engagement Series sessions.

Equity and human rights

Equity and human rights are core underlying principles that require stronger language throughout the Agreement. Priorities include addressing the social and economic determinants of health, the needs of vulnerable and marginalized populations, equitable representation in decision-making, and ensuring equitable access to resources and benefits. Adding an article that explicitly commits to human rights and collaboration with LMICs may be the best way to address this deficit.

Capacity building

Effective pandemic preparedness, response and One Health measures will require substantial global investment, particularly in LMICs, to build capacity and address disparities in pandemic surveillance, public health infrastructure, and health and care systems. Strong engagement and knowledge sharing across HICs, LMICs, governments, academia, NGOs and industry will be essential, as will sustainable funding mechanisms to support multidisciplinary research and development.

International collaboration and standardization

The development of international standards is needed to ensure consistency and interoperability in pandemic surveillance, data collection and reporting, technical training, and biosafety protocols. Collaboration among international partners will facilitate data-driven decision making, particularly in the planning and implementation of public health measures. Regulatory harmonization and multi-jurisdiction approvals will speed the availability of vaccines and other medical countermeasures.

Information and knowledge sharing

The open sharing of information and know-how, including local knowledge and lived experience, is essential to preparedness, rapid response and the timely development of pandemic countermeasures. Channels of communication and collaboration between governments, communities, researchers and the private sector must be established in advance of crises, and the information conveyed must be translated appropriately for its intended audiences.

Transparency and community engagement

Transparency in decision making, communications, the implementation of public health measures and the obligations of private organizations will be critical for maintaining trust in public institutions and the pandemic response. Diverse stakeholder groups must be involved in all aspects of pandemic prevention, preparedness and response, including the research and development of pandemic products.

Access to the benefits of pandemic products

Public and private interests must be balanced to ensure access to medical countermeasures and minimize the human toll of pandemics. Pricing and availability must be equitable for all countries. At the same time, incentives must be maintained to spur innovation and encourage private sector participation in pandemic response. Appropriate and transparent approaches to licensing and intellectual property will be needed. Ensuring distributed production and maintaining open, robust supply chains will improve access and help to counter protectionist tendencies.

Sustainability

Sustainability is an important consideration in many areas. Healthcare and allied health workforces must have sufficient capacity to meet surges in demand during what may be extended crisis periods. The capacity of research infrastructure must be maintained to ensure that pandemic readiness can be ramped up as needed. Sustainability also extends to the production and use of vaccines and pandemic products, including waste management which is a significant issue in remote communities and LMICs. In each case, equitable long-term investments are necessary.

Challenges faced by Indigenous, marginalized and remote communities

These communities face many challenges that make them more vulnerable to the impacts of a pandemic. Limited capacity for public health surveillance, data collection, and prevention and control measures; limited lab capacity; lack of clean water; insufficient housing; mistrust of vaccine rollouts and healthcare systems; and inconsistent translation of public health messaging. In addition, the sovereignty of Canadian Indigenous peoples must be considered when implementing whole-of-government approaches to pandemic response.

Lack of clarity on obligations and compliance

Member states have varying capacities, priorities and obligations under the Agreement, but greater clarity is needed as to how its various provisions will be implemented in practice. Some of the many areas identified as requiring further detail include data sharing, access to pandemic products, fair remuneration for the health and care workforce, communications, private sector obligations, technology transfer and licensing, the distribution of responsibilities among member states, and the enforceability of human rights protections. The document also lacks specifics on mechanisms for monitoring compliance with the provisions of the Agreement and consequences for failure to comply.

Conclusion

In summary, the engagement series on the development of the WHO's Pandemic Agreement provided a platform for diverse stakeholders to contribute valuable insights across various articles. Attendees emphasized the need for a broad-based approach to prevention, encompassing upstream factors and integrated measures across domains, while also highlighting the importance of public health surveillance, data standards, and inclusivity. Challenges faced by Indigenous and remote communities underscored the necessity for addressing disparities in capacities and resources. International collaboration, equity considerations, and sustainability emerged as key themes across multiple articles, emphasizing the importance of harmonization, capacity building, and balancing public and private interests. Moving forward, implementing clear mechanisms for enforcement, promoting transparency, and fostering equitable access and collaboration will be critical for the success of the Pandemic Agreement in effectively addressing global health challenges.

Annex A: Winnipeg (English, in-person)

Participants

The Winnipeg session took place on January 29. Nine participants attended the session representing areas including public health, primary health care, emergency management, Metis government, vaccine research, and youth. Attendees that agreed to share personal information (n=5) identified as or affiliated with an organization representing the following: Visible minorities (31%), women (42%), and youth (29%). Also in attendance was a local Elder, who offered an opening prayer, and 2 representatives from the federal government, including the Team Lead for the Pandemic Instrument Team.

Article-specific input

Article 5: One Health

Participants noted that implementation will be a key issue. The circumstances and context in each jurisdiction will have to be taken into account. For example, capacities for surveillance for zoonotic outbreaks may vary among provinces, which is a similar concern among LMICs. Standards appropriate to regions and contexts should be established for how surveillance is conducted.

One participant highlighted the important role of private sector actors, such as the agricultural industry, and the need to promote collaboration and cooperation. A suggestion was made that academia could be an avenue through which industry could be incentivized to work more closely with public health.

Some participants felt that climate change and planetary health are central to One Health considerations and should feature more prominently in this article.

Article 6: Preparedness, readiness and resilience

Participants noted that the Agreement is legally binding only on the federal government, not the provinces and territories. This could represent a gap in the Canadian healthcare context. It was also noted that domestic levels of government, as well as the governments of many other countries, are reducing spending in some areas of the healthcare system following COVID-19, which is an important consideration as we look to strengthen pandemic response and baseline healthcare capacities through this Agreement.

The COVID pandemic highlighted the fact that typical health emergency surge capacity plans are not sufficient or unsustainable. The Agreement should contain language around sustainability for extended pandemic events.

The Agreement refers to "universal health coverage" in relation to equitable access, but this cannot be mandated. Participants felt this was impractical and that HIC standards of health care cannot be imposed on LMICs. "Equitable" might be a better word than "universal".

Article 7: Health and care workforce

Previous health emergencies are often forgotten when it comes to preparedness and ongoing funding. Sustainability should be a key aspect of Article 7, but, as mentioned above, it is not clear how this would filter down from the federal government to the provincial level. Metis representatives noted that federal healthcare standards are often different for Indigenous groups within a province as compared to the provincial standards for the remaining population of that province.

Surge planning must be expanded to all aspects of health care, including education and health human resources (HHR). Language should be included to acknowledge the limits of an individual's work capacity, even in the face of a pandemic. This is essential to safeguard the physical and mental health of healthcare workers. One solution for dealing with staff shortages could involve implementing national temporary licensing to facilitate transitions between jurisdictions.

The article refers to an internationally deployable health workforce. How will this workforce be built, especially in light of the existing HHR shortages in many countries? Brain drain from LMICs to HICs must also be addressed.

Article 10: Sustainable production

Member states will play various roles in the production and/or utilization of pandemic response products, and such roles should be defined. The International Lifesaving Federation provides point people to help LMICs access relevant information, and such a model could be beneficial in this context.

Sustainable usage of pandemic response products should also be addressed, including promoting efficient use, waste reduction, potential for recycling, and implementing effective roll-out planning to avoid expiration of vaccines, etc. This point applies to Article 13 as well.

Article 12: Access and benefit sharing

South Africa shared Omicron data early, but received nothing in return for taking that risk. Pathogens and IP must be shared, but this is a complex issue. However, sharing data, information or samples may not always result in specific products or other directly related outputs. Benefit sharing may therefore require a broader definition to incentivize both HICs and LMICs.

Although the private sector is not a party to the Agreement, the document should include clear mechanisms for the sharing of intellectual property. A partnership approach that involves sharing proceeds with LMICs could provide incentives for all parties involved.

Furthermore, the question of uncertainty surrounding the emergence of new variants or pathogens should be addressed. It's impossible to predict where and when a new variant or pathogen will emerge.

Article 13: Global supply chain and logistics network

Diversifying the type and source of products will make systems more resilient and reduce the likelihood of shortages or bottlenecks. As noted under Article 10, sustainable usage of vaccines, PPE, etc. should also be addressed.

Article 17: Whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches

While the article focuses on whole-of-government approaches, emergency management is another well-established approach. Whole-of-government brings politics into play more readily than emergency management does. In addition, emergency management demonstrates a similar ability to broadly access government resources at federal and provincial levels. This prompts the question on whether whole-of-government really is the best approach for responding to a pandemic.

One participant noted that the article should specify a "whole-of-governments" (plural) approach, and expand its scope to include other governments and communities, given that Indigenous governments have jurisdiction over their own people. It would be beneficial to consider the terminology used by New Zealand and Australia regarding their Indigenous populations.

Furthermore, the article only briefly mentions the social and economic determinants of health and mental health consequences. These aspects should be given greater importance.

Article 18: Communication and public awareness

Addressing misinformation/disinformation risks is critical in effectively responding to pandemics. Several countermeasures were suggested, including improving fundamental science and health education, monitoring media to maintain situational awareness, and finding ways to make social media platforms accountable for the impact of their algorithms. These efforts align with Article 17, Section 17.3.

Moreover, proactive communication and messaging can disseminate credible information more rapidly. However, it is important that the flow of information remains consistent and transparent, explaining the rationale behind decisions and acknowledging why messages change as new information emerges. This relates to Article 9, Section 9.4.

Communication and public messaging should embody principles of equity and cultural sensitivity, though employing other terms, such as "social justice", could be a way to avoid misinterpretation of the term "cultural sensitivity".

Article 20: Financing

Financing should be addressed for every article.

Other concerns and missing elements

Participants noted some elements they found to be missing from the Agreement. These included no mention of reconciliation in the document and a lack of language addressing long-term health consequences, such as the impacts of long COVID on roughly 20% of those infected.

There was concern raised about use of the term "developing countries"; however, PHAC staff indicated that this designation has implications for the responsibilities a given country has under the Agreement.

Equal representation in the engagement process was also identified as a concern.

Key takeaways

Sustainability

Sustainability emerged as an issue in different ways across several articles. Concerns related to ongoing surge capacity for extended pandemic events, impacts on the health and wellness of healthcare workers resulting from personnel shortages and excessive overtime, and sustainable usage of vaccines and pandemic response products.

Jurisdictional challenges

Different jurisdictions have varying, and sometimes conflicting, capacities, priorities and commitments under the Agreement. For HICs and LMICs, these differences can relate to the capacity to carry out commitments such as surveillance for zoonotic outbreaks, realistic standards for provision and access to health care, or the retention of HHR. In the Canadian context, the federal government is bound by the Agreement, while provinces, territories and the private sector are not.

Recognizing the unique needs to Indigenous populations

The unique needs of Canadian Indigenous populations must be taken into account. Considerations include the differences between the federal healthcare standards that apply to them and the standards of the provinces in which they may reside, and the sovereignty of Indigenous peoples in relation to whole-of-government approaches to pandemic response.

More granular implementation/operationalization

There was a general sense among participants that the articles are constructed and written too broadly. Greater detail is needed to understand how the Agreement can and will be implemented.

Annex B: Montreal (French, hybrid)

Participants

Three participants attended the hybrid session in Montreal on the morning of January 31, representing the areas of health care and public health. Attendees that agreed to share personal information (n=2) identified as or affiliated with an organization representing the following: Women (100%). Also in attendance was a local Elder, who offered an opening prayer, and 2 representatives from the federal government, including the Team Lead for the Pandemic Instrument Team.

Article-specific input

Article 6: Preparedness, readiness and resilience

The Global North should draw on the experience and know-how of communities with less capacity. Ebola management and One Health approaches are examples. Southern countries and First Nations Peoples have valuable insights based on lived experience. (Note: This comment also relates to Article 5: One Health.)

There is a risk of losing much of the lessons learned during the pandemic. It is difficult to re-engage and re-mobilize people as they seek to put the past behind them and move on.

The Agreement should explicitly highlight the negative impacts of health restrictions witnessed during COVID-19.

Article 9: Research and development

It will be important to lay the groundwork for rapid research and development. This includes establishing channels of communication between research institutions and government in advance of public health emergencies and activating these channels during crises, establishing ways to pool knowledge quickly, and enhancing data literacy at all levels. The UK can serve as a model for implementing research to generate conclusive data rapidly. Community representatives should be involved to build and maintain trust.

Article 12: Access and benefit sharing

The divide between private medical research and the democratization of the response must be considered. Questions remain regarding the obligations of private organizations to share the benefits of vaccines and other pandemic response products. Despite receiving large investments, there is often little return for the community.

Other concerns and missing elements

Participants questioned whether the WHO has the agility to respond quickly enough to a rapidly evolving crisis. One participant identified PR3CRISA (Prevention Research Network Responses and Resilience to Health Crises) as an organization capable of providing rapid responses.

Key takeaways

Information and knowledge sharing

Sharing information and know-how is essential to preparedness, rapid response and rapid development of pandemic countermeasures. There is a call for establishing channels of communication and collaboration between different stakeholders, including researchers, governments, and communities, both in advance of and during crises. This includes pooling knowledge quickly, building data literacy, and learning from models like the UK's approach to research.

Community engagement and participation

Across all articles, there is a recurring emphasis on the importance of involving communities in various aspects of preparedness, research and development, and access to benefits. This includes leveraging the knowledge and experiences of communities with less capacity, engaging community representatives in research processes, and considering the obligations of private organizations to share benefits with the community.

Equity and inclusivity

There is a focus on addressing disparities and ensuring equitable access to resources and benefits. This is evident in discussions about drawing on the experiences of Southern countries and First Nations, as well as considerations of the democratization of pandemic response and access to benefits from medical research.

Long-term preparedness and sustainability

There is recognition of the need to not only respond to immediate crises but also lay the groundwork for long-term preparedness and resilience. This involves preserving and building on lessons learned from past experiences, as well as considering the long-term impacts of health restrictions and the obligations of private organizations.

Annex C: Online 1 (English, virtual)

Participants

The first online session was held in the afternoon on January 31. Nineteen participants attended the session from a variety of different sectors including: healthcare (academic medicine, long-term care, allied health (dental hygiene, pharmacy), long COVID care, ophthalmology, palliative care), public health, global health, clinical research, One Health research, veterinary medicine, bioethics, racialized groups and the private sector. Attendees that agreed to share personal information (n=17) identified as or affiliated with an organization representing the following: Indigenous peoples (23%), persons with disabilities (23%), visible minorities (29%), women (35%), youth (11%), and 2SLGBTQQIA+ communities (29%). Also in attendance was a local Elder, who offered an opening prayer, and 2 representatives from the federal government, including the Team Lead for the Pandemic Instrument Team.

Article-specific input

Article 4: Pandemic prevention and public health surveillance

Participants raised multiple challenges related to data collection and sharing, especially. Rural, remote and Northern communities, in particular, face a number of issues, including a lack of data standards and small population sizes, making data sharing difficult. Outdated information systems and privacy legislation also limit their ability to participate fully in collaborative efforts. Data ownership, inclusivity (e.g., race-based data) and cultural sensitivity are important issues which need greater consideration. It was noted that the Auditor General of Canada issued recommendations for the sharing and ownership of data in 2022 and that the UK has demonstrated ways to collect and share data appropriately.

Several participants stressed the importance of interoperability, particularly emphasizing the major role academic research played in generating COVID-related data. They advocated for formalized collaboration channels between government and academia. Concerns were raised regarding subsection 4.4 (f), noting that biosecurity concerns make conducting research during a pandemic more challenging.

Capacity issues were discussed in a variety of ways. Remote communities often do not have the necessary funds to implement optimal infection prevention and control measures, while the ability to implement oral health prevention measures varies greatly across Canada. Addressing diagnostic capacity under subsection 4.3, will not be sufficient. Pathways will be needed to expedite specimen flow from clinical labs to government labs in order to minimize delays. Greater lab capacity is needed in the NWT, including necessary human resources.

Regarding prevention, the issue is broader than what is referenced in Article 4. Public trust, baseline health literacy, and rapid municipal response are integral aspects of an effective prevention plan. A noticeable gap exists regarding responsibility for providing guidance on prevention and control of disease outbreaks in the community outside of healthcare settings. An important part of the prevention measures that Canada implemented for COVID were social supports. It is not acknowledged that the Global North spent much more on these and other domestic prevention measures than on global support.

Subsection 4.4 (e) emphasizes the importance of One Health, urging its integration across all sections of the Agreement.

Article 5: One Health

Some participants expressed concerns that this article was written at so high a level that it might hinder its effectiveness, suggesting that the integration of One Health needs to be done thoughtfully to avoid ongoing siloes. More detail is needed about specific actions.

Regarding Subsection 5.7, it is difficult to access funding for the interdisciplinary work that One Health requires. Participants called for targeted funding and a culture of intellectual openness to support this type of collaborative effort.

Article 6: Preparedness, readiness and resilience

Critical to preparedness is recognizing that the impacts of a crisis can extend into the medium and even long term. Improved longitudinal studies and sustained funding are necessary to understand the causes and monitor the consequences at individual, community and national levels. A large part of preparedness, readiness and resilience rests in how members of society interact with each other. It was also noted that we need to think about equity more broadly.

Participants identified public health as key to this article and emphasized that it will be important to promote the enhancement of public health institutions in all countries and strengthen their voices during pandemics. Concerns were raised about the declining investment in public and other health systems, underscoring the need for sustainable support to ensure capacity. The regulatory and legal tools that public health departments use to implement public health measures quickly should be protected, and public health institutions should be shielded from political interference.

Some participants felt the text downplays the fundamental importance of healthcare resilience and the mental health impacts that caused personnel to leave the system. Mental health supports should be specified. (Also see Article 7.) Resilience is also an issue for the minority groups that staffed service jobs where they were put at high risk. Additionally, members of various cultural communities expressed reluctance in seeking care for long COVID because they felt they would not be believed, highlighting the need for better engagement with these communities.

Comments directly related to care included accelerating the translation of knowledge to practice and putting greater emphasis on a palliative approach, which becomes more critical in a pandemic. The establishment of an international consortium on palliative care was proposed to address this.

Article 7: Health and care workforce

Workforce considerations should be strengthened to safeguard health and care workers broadly and to help ensure workforce capacity. Multiple participants raised the issue that the health care workforce is broader than doctors, nurses and hospitals and recommended the inclusion of the allied workforce. Pharmacy professionals were specifically highlighted for their critical role in addressing healthcare gaps, managing drug shortages and supporting the public health response. The following link was submitted in support of this point:

Some felt consideration should be broadened further to include workers in essential pandemic roles such as logistics and manufacturing. To support surge response, workers beyond healthcare professionals could be used to provide additional manpower and resources.

Missing elements included how foreign healthcare workers would be dealt with post-pandemic. These and other non-unionized healthcare and human resource sectors, such as migrant care workers, may not be able to advocate for themselves in a work environment. In addition, the Agreement does not address how pandemic measures would affect collective agreements.

Article 9: Research and development

Speaking to subsection 9.1, participants highlighted the importance of rapid response to novel threats, emphasizing the need for rapid sharing of information and translation of knowledge. However, formal channels for information sharing tend to work slowly and agreements and contracts can take months to put in place. To address this, mechanisms and frameworks should be developed in advance.

Transparency is critical when working with stakeholders. For example, vaccine hesitancy resulted, in part, because vaccines were rolled out earlier in Indigenous communities due to their higher risk, leading to rumours of conducting testing on those communities. Relationships need to be built ahead of time and opportunities should be created for communities to be part of the research process. Diverse representation in clinical trial could also help address vaccine hesitancy.

The pharmaceutical industry must be incentivized to build laboratories and research facilities in LMICs. This will improve local economic stability and ensure improved access to medicines, vaccines and knowledge. Ways to move innovations through the pipeline from lab to product more quickly are also needed.

A clearer definition of "publicly funded research" is needed. If only a portion of the research leading to a product is publicly funded, how do you determine a threshold for sharing intellectual property? One participant indicated that subsection 9.4 should be redrafted so as not to impose disclosure requirements that will discourage research and delay development of vaccines and therapies.

Article 11: Technology transfer and know-how

A participant suggested removing requirements for the disclosure of trade secrets.

Article 13: Global supply chain and logistics network

One participant expressed concern that subsection 13.7 supports trade restrictions and barriers, which have shown negative effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canada should support open trade and borders instead.

Article 17: Whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches

A comprehensive system is needed to address the social determinants of health. Support should be available consistently, not only during emergency situations.

Article 18: Communication and public awareness

One of the deeper issues in communications and public awareness is trust in public institutions. There is need to build social trust in government institutions and experts in medical, public health, and emergency response fields. Communication and decision-making must be transparent, clear, accurate, consistent and evidence based. Health communication should come from health authorities and experts to minimize the politicization of the pandemic response.

Messaging should be tailored and sensitive to diverse communities, utilizing channels that reflect the intended recipient populations/communities. Lived experience and anti-racism messaging should be part of communications to combat scapegoating. A best practice should be to hold terminology workshops so that interpretation into Indigenous and other languages is accurate and does not result in mixed messages.

Subsection 18.1 should target not only adults, but also the K-12 education systems by integrating public health and pandemic literacy in the curriculum.

Article 20: Financing

Sustainable funding for public health systems should be specified so that the capacity of these systems does not erode in interim periods.

Other concerns and missing elements

One participant expressed concern there is no article directly associated with animal health, though Articles 4 and 5 do relate to it.

Another commented that while there are some good principles in the draft Agreement, it does not seem to be a legal text that is effective, implementable, and enforceable. Much of it is vague and there seem to be no consequences for failure to comply. For instance, there is no formula for financing, no guidance for resolving competing rights (e.g., health vs. intellectual property), no reconciliation of the right to health with state sovereignty, and no protocol for ensuring access for experts to enter countries to conduct pandemic-related investigations, especially when failures of transparency are evident.

Key takeaways

Central importance of public health systems

Concerns here related to enhancing public health institutions in all countries, strengthening their voices during pandemics, ensuring their support, maintaining their capacity, and protecting them from political interference.

Transparency

Participants said transparency in relation to public health measures, decision making and communications is critical for maintaining trust in public institutions and the pandemic response.

Challenges for Indigenous and remote communities

Indigenous communities face a number of challenges related to data collection and public health surveillance, and have limited capacity for implementing infection prevention and control measures, minimal lab capacity, mistrust around vaccine rollouts, and inconsistent translation of messaging into Indigenous languages.

Data and information sharing

Across multiple articles, there was a recurring theme regarding the challenges of data collection, sharing, and standards. The need for interoperability and collaboration between government, academia, and other stakeholders was highlighted to facilitate data-driven decision-making, particularly in public health surveillance and research.

Capacity building and resource allocation

There was an emphasis on the need for enhanced capacity in various areas, including public health infrastructure, diagnostic capabilities, and workforce training. This includes addressing disparities in resource allocation between different regions and communities. Sustainable funding mechanisms for public health systems are advocated for to ensure the continuity and effectiveness of health interventions, including during interim periods between crises.

Equity and inclusivity

Equity considerations should be woven throughout the articles, highlighting the need to address disparities in healthcare access, workforce representation, and community engagement. This includes considerations of cultural sensitivity, social determinants of health, and the inclusion of marginalized communities in decision-making processes.

Annex D: Halifax (English, in-person)

Participants

The Halifax session was held on the morning of February 2. Four participants attended the session representing areas including public health, health research, youth and racialized perspectives. Attendees that agreed to share personal information (n=4) identified as or affiliated with an organization representing the following: women (25%) and youth (100%). Also in attendance was a local Elder, who offered an opening prayer, and 2 representatives from the federal government, including the Chief Negotiator and Team Lead for the Pandemic Instrument Team.

Article-specific input

Article 4: Pandemic prevention and public health surveillance

LMICs could benefit from accessing biosafety and biosecurity expertise from nations with greater expertise. Subsection 4.4 (d) could be made more inclusive by adding research institutions and any facilities where disease vectors are present. Additionally, the article should include investment for antibiotic development.

Article 5: One Health

Some participants felt the scope of the article should be expanded to planetary health, and climate change should be explicitly identified as a driver of zoonotic disease. Concerns were raised about the term "surveillance," noting that it can be loaded, despite its common use in public health circles. The question was raised as to how One Health initiatives will be implemented at the provincial and territorial levels.

Subsection 5.2 should include language such as "relevant" or "inclusive" to help define stakeholder groups.

Article 7: Health and care workforce

Participants made several subsection-specific points:

- 7.1 (a): Competency-based education should be provided for locations where people gather, such as daycare centres.

- 7.2 (b): The subsection should include diversity and emphasize meaningful engagement, specifically acknowledging the role of women and mothers as primary caretakers who are more susceptible to infection, as seen during the Ebola outbreaks in Western and Central Africa.

- 7.2 (c) and (d): Appropriate staffing levels are needed at healthcare facilities to achieve these goals. Addressing burnout among healthcare and long-term care staff must be addressed, and non-critical tasks could be backfilled with temporary and volunteer non-clinical support staff.

Article 9: Research and development

In a pandemic context, knowledge, IP and output sharing should be prioritized. Research knowledge should be translated appropriately for the general public. In subsection 9.3 (d), increasing coordination and collaboration for clinical trials within LMICs will require training and resources to build capacity. This presents an opportunity to further build trusted relationships, requiring further elaboration in the article.

Article 11: Technology transfer and know-how

Know-how should include local, lived and Indigenous experience. Providing a guaranteed purchase price for vaccines or other pandemic products should come with additional requirements for private sector entities.

Article 12: Access and benefit sharing

Public health risks and needs should be assessed in collaboration with on-the-ground partners.

Article 13: Global supply chain and logistics network

Stockpiling should only be allowed within a more comprehensive framework to prevent hoarding that disadvantages other countries and regions. Subsection 13.4 should include a provision that donated materials are not nearing their expiration date. Transport costs for goods donated to LMICs should be eliminated. Enabling local companies to provide PPE will help bolster local economies (see also Article 10).

Article 14: Regulatory strengthening

In subsection 14.3, compensation for false pandemic products should be provided through a restorative justice system.

Article 16: International collaboration and cooperation

Subsection-specific comments included:

- 16.2 (a): We should be wary of making this too political rather than evidence-based.

- 16.2 (d): The term "meaningful" should be included in this subsection for consistency with other articles.

Article 17: Whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches

Participants stressed the need to be cautious about including the private sector in discussions. In subsection 17.4 (d), equitable restoration implies going back to pre-pandemic status. However, we must be sure to incorporate lessons learned and evolve our public health systems.

Article 18: Communication and public awareness

Open, transparent public health communication is critical and can be considered a social determinant of health. Providing consistent, trusted messaging from credible sources across all available channels will help counter the increasing flow of misinformation.

Accessibility and inclusivity must be taken into account, especially as vulnerable groups have limited health literacy. Building relationships with diverse groups will increase trust in public health institutions before crises occur. Community liaisons can help target and reach these groups more effectively. Examples from other countries such as South Korea, which kept cases low for a long period of time, should be explored. Lived experience and traditional knowledge should also be valued.