Protocol for enhanced human surveillance of avian influenza A(H5N1) on farms in Canada

On this page

- Background

- Implementation context

- Methods

- Statistical analysis and reporting of findings

- Ethical considerations

- Reporting obligations

- References

- Acknowledgements

- Contact us

About this protocol

The Protocol for enhanced human surveillance of avian influenza A(H5N1) on farms in Canada has been designed as a proactive tool to support local public health authorities in the event of human infection or in unusual exposure scenarios on Canadian farms with infected livestock. This tool is intended to be used for a limited period of time and is not intended as routine practice. This protocol complements the Public health management of human cases of avian influenza and associated human contacts (AI CCM) and the Guidance on human health issues related to avian influenza in Canada (HHAI).

Provinces, territories (PTs), and local public health units can opt to use this protocol to enhance knowledge on A(H5N1) risk and transmission in Canada and to inform response.

Background

Globally, avian influenza A(H5N1) has been detected for several years in domestic birds. Rare zoonotic human cases have been reported, but, as of publishing, without evidence of human-to-human transmission. As of July 2024, less than 1000 A(H5N1) cases in humans have been reported globally since 2003, with a case-fatality rate of 53% Footnote 1. The rate of asymptomatic disease in humans is unknown; however, of the 35 sporadic A(H5N1) human cases reported globally between 2022 and the beginning of July 2024 [including clades: 2.3.4.4b HPAI A(H5N1), 2.3.2.1c HPAI A(H5N1), 2.3.2.1a HPAI A(H5N1)], 8 (23%) were asymptomatic, 11 reported mild illness (31%), 15 were severe or critical illness (43%), and 7 died (20%) Footnote 2.

Since 2021, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5N1) viruses belonging to clade 2.3.4.4b have been detected worldwide in migrating birds (and other wild species) (see Wildlife dashboard) and domestic birds (see Domestic dashboard), causing large epizootic events with high mortality rates. Avian influenza A (H5N1) clade 2.3.4.4b has also been increasingly reported in an expanded set of mammalian species (marine mammals, wild terrestrial mammals, and domesticated species). Like other countries of the world, Canada has experienced several outbreaks of this virus on farms with domestic birds and sporadic identifications in mammalian species. In the United States, beginning in the spring and early summer of 2024, a number of outbreaks of A(H5N1) were reported on farms with infected domestic birds and cattle in the USA, and several associated human cases have been confirmed (see U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Current situation on A(H5N1) for up-to-date information on the outbreak in the United States). Outbreaks of A(H5N1) had not previously been reported among cattle or in dairy herds.

Unlike cases of A(H5N1) reported globally, the human cases reported in the United States in 2024 with exposure to dairy cattle and domestic birds only reported mild symptoms (e.g., conjunctivitis, fever, chills, coughing, sore throat and runny nose) and all have recovered Footnote 3. There was also limited evidence of mutations associated with human transmission at the time of protocol writing. Of the few human cases that have been reported with the currently circulating clade in the United States (avian influenza A(H5N1) clade 2.3.4.4b), only one marker (PB2 E627K) has been associated with adaptation to mammalian species Footnote 4. Historically, transmission of A(H5N1) from animals to humans has been documented through direct contact with infected birds or contaminated environments, predominantly via exposure to infected birds or their secretions, such as saliva, nasal discharges, and feces, which contain high viral loads Footnote 5. The transmission routes to the human cases working with dairy cattle is unclear but believed to be from cattle to humans through direct or indirect contact with infected animals or their raw or unpasteurized milk. In situations of ongoing contact between infected animals and/or humans, there remains a potential for avian influenza transmission and adaptation to human hosts, which can pose a pandemic risk.

Canadian and international risk assessments (PAHO, FAO-WOAH) have concluded that the risk to humans is currently low but there is an increased risk of spillover events in humans exposed to infected animals, including farm workers (see the Public Health Agency of Canada's (PHAC) pandemic risk scenario analysis for avian influenza A(H5N1) and the Pan American Health Organization's public health risk assessment for avian A(H5N1) influenza). A recent update to PHAC's Pandemic Risk Scenario Analysis suggested that "there was strong agreement that the situation has worsened from last year [2023] due to more mammalian infections creating a significant opportunity for viral adaptation to mammals. Cattle might also be a new mixing vessel with opportunities for reassortment with influenza viruses of mammalian origin, though this is uncertain" Footnote 6. Specifically, there is concern that infection of mammals offers opportunities for the virus to reassort, potentially gaining properties that allow it to transmit more efficiently between humans.

Considering knowledge gaps around A(H5N1) transmission, scientists have recommended that enhanced surveillance activities target individuals at higher risk of exposure to inform subsequent risk assessment activities and enhance PHAC's scientific pandemic preparedness posture. Ongoing existing surveillance is likely to capture severe cases with high-risk exposures that present to public health Footnote 7. However, given the recent increase in mild cases observed in the US, and evidence of missed symptomatic cases on farms in Texas Footnote 8, there is a need to outline a process for sensitive case finding in the event infection is detected on farms in Canada.

A key benefit to the development of the parameters for enhanced human surveillance ahead of the detection of human cases of A(H5N1) in Canada is to generate consensus from a One Health perspective around when an enhanced human health investigation should take place (criteria for implementation), why it should happen (what it will help us to better understand about the virus) and to ensure it is coordinated with on-farm investigations being conducted by other federal, provincial, and territorial (F/P/T) One Health partners. Standardized surveillance protocols already adapted to the Canadian context, also speed up local implementation and promotes ease of roll-up and national interpretability of findings that may be generated from multiple sites Footnote 9across Canada.

Purpose and objectives

This protocol describes a time-limited public health response on Canadian farms to more comprehensively and actively assess A(H5N1) transmission risk to humans from infected animals, investigate likely exposure pathways, and promote early detection of A(H5N1) mutations that could pose a risk to human health (e.g., mutations associated with increased transmissibility, severity, decreased antiviral effectiveness). Evidence generated is expected to inform surveillance case definitions, guidance around prevention of cases (e.g. PPE recommendations), case and contact management, future risk assessments, testing and vaccination policies.

Note: we define farms as establishments primarily engaged in growing crops, raising animals, harvesting timber, harvesting fish and other animals from their natural habitats and providing related support activities. Herein we define farm as those specifically associated with livestock. The term livestock includes: dairy and beef cattle (including feedlots), pigs, poultry and eggs (including hatcheries), turkeys, ducks, geese, sheep, goats, horses and other equines, bison (buffalo), elk (wapiti), deer, llamas and alpacas, rabbits, mink, bees and other animals Footnote 10.

Objectives

- To determine whether transmission of A(H5N1) from infected on-farm animals to humans has occurred and to assess whether human-to-human transmission has occurred.

- To identify the most likely mode(s) of transmission of A(H5N1) from animals to humans, and between humans.

- To collect specimens that could be used for genomic testing to assess epidemiology and viral characteristics relevant to public health (e.g. virulence, transmissibility, antiviral resistance).

- To identify the exposure and individual risk factors associated with human infection with A(H5N1).

Summary of approach

We describe time-limited active human case finding as part of an on-farm investigation based on pre-defined criteria. This would involve:

- Voluntary testing of everyone exposed to farms associated with recent laboratory confirmed A(H5N1)-infected animals or humans (nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal and conjunctival swabs and blood samples (serological testing)).

- Administration of an epidemiologic questionnaire to all individuals (both cases and contacts) to ascertain exposures and individual risk factors.

The Public Health Agency of Canada recommends enhanced human surveillance and has developed this protocol in consultation with F/P/T One Health partners. Its implementation should be determined based on provincial and territorial public health department needs. This protocol should be interpreted and applied in conjunction with other relevant provincial, territorial (P/T) and municipal legislation and policies. It is not intended to replace local public health response activities, nor the personalized public health advice provided to individuals or groups of individuals, based on clinical judgment and comprehensive risk assessments conducted by public health authorities.

Implementation context

Enhanced human surveillance is only one component of a broader One Health response to A(H5N1) in Canada. Please see Avian influenza A(H5N1): Canada's response for up-to-date details on the broader surveillance, monitoring and preparedness actions. In the context of an A(H5N1) outbreak on a farm in Canada, in addition to the enhanced surveillance approach proposed here, concurrent action and response will likely be undertaken by other partners including the appropriate public health authority who will lead human case and contact management and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), industry and animal health partners who will lead on-farm investigations focused on animal health.

Concurrent on-farm investigations

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), including A(H5N1) is a federally reportable disease in any species Footnote 11. As of July 25, 2024, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency's (CFIA) response to HPAI A(H5N1) in cattle primarily involves providing scientific advice, diagnostic support, and international reporting, rather than taking a leading role as with HPAI detection in domestic birds. The CFIA collaborates with provincial, territorial, and industry partners to collect data, manage the disease and emphasize biosecurity measures. In the event of a positive detection of a mammalian species on a farm in Canada, CFIA, industry, animal health, public health or other local and regional partners would respond and conduct an outbreak investigation. Extensive Premises Investigation Questionnaires (PIQ) for avian influenza have been developed (specific to avian and cattle) by CFIA, capturing data on affected premises, contacts, operations, animals, site, plans, barns, structures, biosecurity, safety measures, feed, bedding, likely introductions and response measures. Given the criteria outlined above, on-farm animal, public health, or occupational health investigations would likely already be underway when implementing this enhanced surveillance approach, so we strongly encourage coordination with the animal outbreak investigations and potential data sharing agreements to complement ongoing farm activities (for example, see the Guidance on human health issues related to avian influenza in Canada - Principles for information sharing to support public health action).

Existing public health guidance

The enhanced surveillance approach described here is complementary to the Public health management of human cases of avian influenza and associated human contacts (AI CCM).The AI CCM guidance provides non-subtype and non-strain specific recommendations for case and contact management of avian influenza in Canada. Public health recommendations are made to manage human cases of avian influenza – regardless of the source of exposure – and their human contacts. The enhanced surveillance approach outlined in this protocol differs in that it recommends time-limited, active case finding in all exposed persons (to both human and animal cases), including asymptomatic persons. Any active case identified as a part of enhanced human surveillance activities would be managed by the appropriate local jurisdiction according to the AI CCM protocol.

The Public Health Agency of Canada has also published the Guidance on human health issues related to avian influenza in Canada (HHAI), which provides recommendations for public health authorities and other partners involved in the management of actual and potential human health issues related to avian influenza outbreaks in animals. The HHAI includes public health recommendations for the management of individuals following exposure to an infected animal and the management of individuals following exposure to infected wildlife or their environments and those involved in animal outbreak situations.

When to implement this protocol

The criteria to activate this enhanced surveillance protocol have been proposed based on the current evidence and epidemiology available as of fall, 2024. Consideration should be given to implementing enhanced surveillance when one of the four criteria below are met. When criteria for implementation have been met, we recommend steps to verify how the criteria were met, conducting a preliminary risk and feasibility assessment, using jurisdictional governance mechanisms to decide whether to proceed with implementation, confirming the enhanced surveillance objectives, and documenting the rationale and expected public health benefits and actions. The decision to implement is at the discretion of the jurisdiction and these criteria are not meant to be exclusive; jurisdictions may consider implementation in situations and or settings where new or unexpected events occur that have not been defined here.

Criteria for enhanced surveillance activation related to new introductions into Canada

- Positive laboratory-confirmed detections in humans on farms with infected animals (regardless of animal species).

- Enhanced surveillance would be used in tandem with the emerging respiratory pathogens and Severe Acute Respiratory Infection (SARI) case report form and the Public health management of human cases of avian influenza and associated human contacts (AI CCM) guidance for farms with positive human detections of A(H5N1) (regardless of whether they are symptomatic or asymptomatic).

- Laboratory-confirmed detection (PCR) in a new livestock species in Canada where there is a strong likelihood of animal-to-human contact.

- Enhanced surveillance would be used for the first few farms on which a new animal species has been infected in Canada.

- Positive animals may be identified through a number of means, such as:

- Testing of animals conducted by private veterinarians, labs or CFIA.

- Positive milk samples, other raw or unpasteurized dairy or animal products (e.g., cheese, eggs, meat), animal tissue or carcasses, or wastewater samples that can be traced back to infected animals on specific farms.

Note: Enhanced surveillance activated as a result of criteria #1 or #2 above may be discontinued after investigation of the first 10 affected farms, depending on their size.

Criteria for enhanced surveillance activation once virus already established in animal populations in Canada. For both criteria, a positive PCR in an infected animal or human on-farm would also be required.

- Unusual, laboratory-confirmed, infection in livestock where there is a strong likelihood of animal-to-human contact. For example:

- A sudden change in the epidemiology of the virus that suggests an increase in the transmissibility or severity of the virus (e.g., large mortality event)

- An unusual event occurs which increases high-risk contact between humans and infected farm animals (e.g. breakdown of PPE during slaughter)

- There is an increase in the vulnerability of the population being exposed to infected livestock.

- A genetic mutation is identified in an H5 strain linked to a farm animal infection in Canada that suggests increased risk to humans

- There is scientific evidence of sufficient quality to indicate that the mutation(s) results in, or is likely to result in, epidemiologically significant outcomes (e.g., increased transmissibility based on changes in receptor binding, increased severity, changes in susceptibility to medical countermeasures)

Methods

Testing approach

The enhanced surveillance approach recommended here acknowledges the unknown relationship between the first positive detection of A(H5N1) on a farm (and the start of enhanced surveillance) and when individuals were first exposed to A(H5N1); by the time A(H5N1) is detected, the virus may have been circulating on-farm for some time or, detection may have happened early in the course of the outbreak, meaning that human exposure might not yet have occurred. The proposed approach seeks to maximize the probability of detecting infections, should they occur, by selecting testing points that maximize the exposure period that is 'covered' by the testing approach.

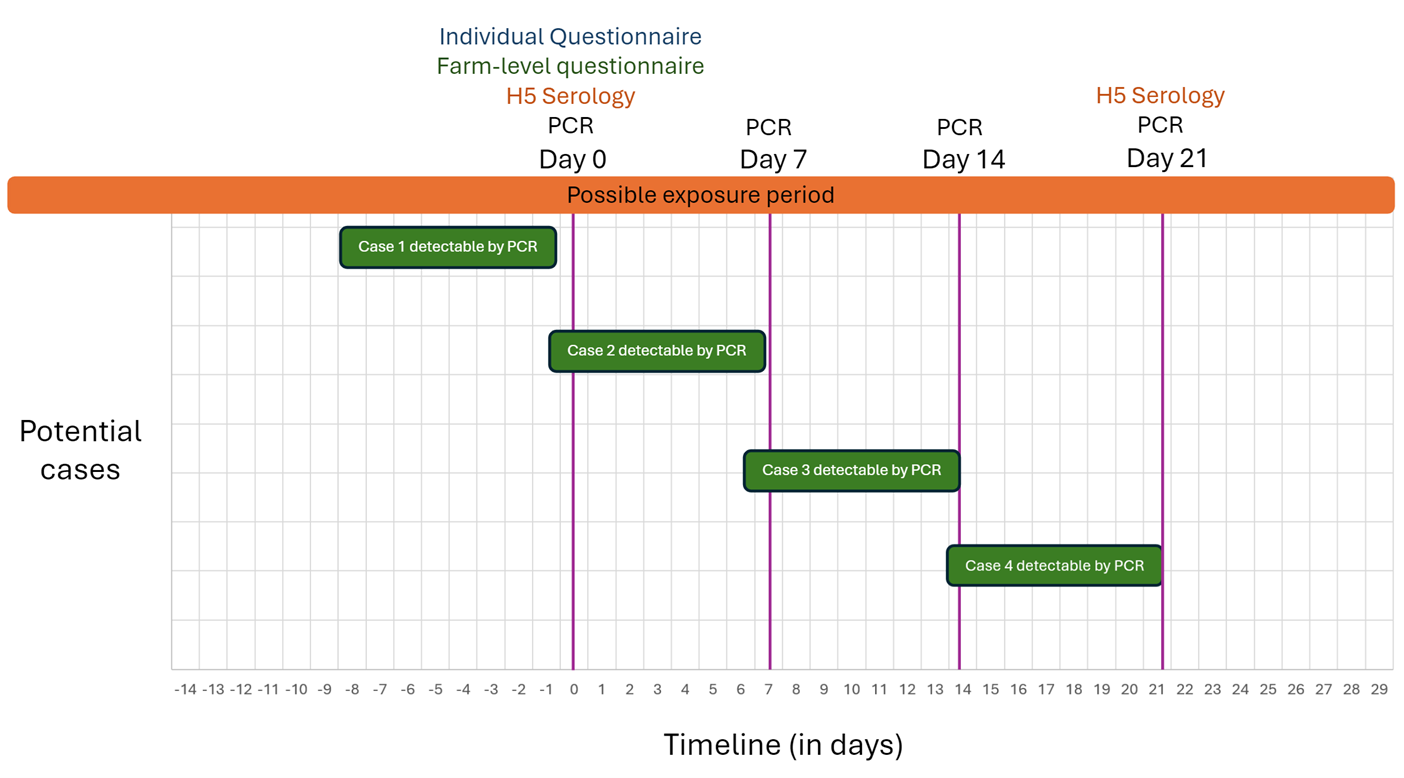

Based on available information about the incubation period and period of viral shedding of A(H5N1) Footnote 12Footnote 13, RT-PCR is expected to detect the virus' genomic ribonucleic acid, if present, following incubation of 1-4 days, and up to approximately 10 days after infection. Therefore, the median interval when the virus' genomic material is expected to be detectable by PCR is ~2-7 days after exposure. If Day 0 is considered the date that enhanced surveillance is initiated, collecting samples on Days 0, 7, 14 and 21 provides sufficient coverage of the exposure period to capture active human infections caused by exposure at or after the start of the event (characterized by onset date of symptoms or initial positive RT-PCR detection in an animal or human) (Figure 1). If resources permit, jurisdictions may consider repeat RT-PCR testing (and subsequent serology) beyond 21 days, continuing at 7-day increments until 10 days after the animal outbreak is declared over or exposure has ended.

Serology assessments at the beginning (Day 0) and end (Day 21) of the period of enhanced surveillance will capture instances where exposure and infection occurred sometime prior to the start of enhanced surveillance (indicated by a positive serology detection at Day 0), or during the surveillance period but outside of the median detection window for RT-PCR (positive serology detection at Day 21), (Figure 1). In addition, paired sera are required to confirm any active infection discovered through active surveillance. The serum sample taken at Day O for everyone will be considered the acute sample with a convalescent sample taken 21 days after any positive RT-PCR test.

Figure 1 – Text description

The figure displays a timeline showing sampling events for four example H5 cases with ongoing exposure and varying onset dates during the surveillance period. The timeline starts 14 days before sampling begins and ends 29 days after (and includes the proposed sampling days at Day 0, Day 7, Day 14 and Day 21). Day 0 activities include the Individual Questionnaire, the farm-level questionnaire, H5 serology, and PCR testing. On Day 7 and Day 14, only PCR testing is conducted, while Day 21 includes both H5 serology and PCR testing. Three cases marked as PCR-detectable at different time points.

Eligibility criteria

Any individual living on, working on, or visiting a farm within 38 days of the identification of a laboratory-confirmed A(H5N1)-infected animal species (e.g., dairy cattle, beef cattle, goats, pigs, mink, dogs, cats, mice) or human on that premises.

Note: As of September 4, 2024, the observed timeline of H5N1 outbreaks in dairy farm settings was less than four weeks Footnote 14. Given the current recommendation of the CDC to monitor for symptoms and illness from the date of first exposure until 10 days after their last exposure Footnote 15, we assess the risk period to be 38 days after the identification of the first infected animal is detected.

Case definitions

The following case definitions for human infections with avian A(H5N1) virus are from the public health management of human cases and contacts associated with avian influenza (AI CCM) and have been defined for the purpose of case classification and reporting to the Public Health Agency of Canada. They are based on the current level of epidemiological evidence and uncertainty and are subject to change with ongoing monitoring and as understanding of avian influenza characteristics and risk assessments evolve.

Probable case

A person who has influenza A results suggestive of a non-seasonal influenza strain pending confirmatory test results by the NML and/or provincial/territorial public health laboratory

- and meets the exposure criteria, regardless of symptoms

- or has symptoms compatible with illness criteria

Note: A positive non-seasonal influenza A test is appropriate when there is no alternative etiologic hypothesis. For example, an individual who meets the exposure or illness criteria and is positive for influenza A and is negative for A(H1) and A(H3) should be included in this definition of a probable case. However, an individual who tests positive for influenza A and an H3 is not a probable case.

Note: Efforts to obtain additional specimens to clarify case status may be warranted.

Confirmed case

A person with laboratory confirmation of influenza A(H5N1) infection at Canada's National Microbiology Laboratory (NML).

Exposure criteria

Exposure within the previous ten (10) days to any of the following: direct or indirect close contact (within 2 metres) to presumptive or confirmed infected birds or other animals (e.g., visiting a live market, touching or handling infected animals, under- or uncooked poultry or egg), close contact (within 2 metres) with a probable, or confirmed human case; unprotected exposure to biological material (e.g., primary clinical specimens, virus culture isolates) known to contain avian influenza virus in a laboratory setting, or unprotected, direct or close contact (within 2 metres) to contaminated environments. Exposure to contaminated environments includes: direct contact with surfaces contaminated with animal parts (e.g., carcasses, internal organs), bodily fluids ( e.g. respiratory secretions, milk, urine), or feces from A(H5N1) infected animals Footnote 16 or settings in which there have been mass animal die offs in the previous 6-8 weeks due to A(H5N1)Footnote 17Footnote 18. This period is based on limited evidence from experimental studies Footnote 17Footnote 18. There is insufficient evidence regarding other factors potentially affecting virus survivability, such as temperature, airflow, type of surface material and fallow period.

Illness criteria

Illness onset is defined by the earliest start of SARI or ILI. SARI symptoms are fever (over 38 degrees Celsius), and new onset of (or exacerbation of chronic) cough or breathing difficulty and evidence of severe illness progression Footnote 17. ILI is defined as acute onset of respiratory illness with fever and cough and one or more of the following: sore throat, arthralgia, myalgia or prostration, which could be due to influenza virus Footnote 19. In children under 5, gastrointestinal symptoms may also be present. In patients under 5 or 65 and older, fever may not be prominent. If the index of suspicion is high and depending on clinical judgement, individuals with the following additional signs and symptoms may also be considered as meeting illness criteria: rhinorrhea, fatigue, headache, conjunctivitis, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, pneumonia, diarrhea, respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, neurologic symptoms, or multi-organ failure Footnote 20. The variation in spectrum of illness ranges from mild, atypical to severe Footnote 20.

Data collection

Standard public health practice for consent and engagement should be followed including: explaining to each eligible individual (or their guardian) the questionnaires, viral swabs and blood samples, potential benefits and risks, the right to refuse (or opt out of some components) and an opportunity to ask any questions they may have.

All processes and documentation will be provided in English and French, with additional language options provided as needed by eligible individuals (e.g., Spanish).

Epidemiological questionnaires

The main questionnaire is intended to be completed by all eligible individuals on Day 0 (see Appendix – Individual Questionnaire). It collects information on demographics, individual risk factors (e.g. underlying medical conditions, smoking, previous influenza immunization), and typical exposures to animals that would be incurred in the course of daily work or presence on the farm. These exposures are broken into 3 sections – for beef or dairy cattle, for poultry, and for other animals. Since the risk of transmission is dependent on several factors including the type of interaction with the animals, the duration of that interaction, whether the contact was with healthy versus sick or infected animals, and whether PPE was used, the questions have been structured to examine these interactions. Skipping patterns have been included to reduce the length when interactions with animals have not occurred. The individual questionnaire was developed to align with the Emerging respiratory pathogens and Severe Acute Respiratory Infection (SARI) case report form. The questionnaire has not been pilot tested.

A second farm-level questionnaire will capture items such as the type and number of animals on the farm, the number of sick animals of each species, the number of workers, visitors, residents, and farm size(See Appendix – Farm questionnaire). It is meant to characterize the farm setting and the general context of the animal outbreak; updates as the outbreak progresses will be required. The farm level- questionnaire was developed to align with CFIA's premises investigation questionnaire (PIQ) and data may be pulled directly from the PIQ if feasible.

Daily diaries (See Appendix – Daily diary log) will be provided to each individual to record their daily presence on the farm premises and symptoms including body temperature, feverishness, cough, sore throat, headache, myalgia, coryza, phlegm, etc. each day. Daily logs will be self-reported by all individuals aged 12 years or older, and proxy reported by adults for any children below the age of 12. The CDC has implemented a mobile system to capture these data via text message and Fluwatchers utilizes a secure email link; both approaches could reduce the burden on individuals and local public health.

Laboratory specimens

This protocol includes three sampling types based on the current epidemiology of the virus in humans (nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal and conjunctival swabs, and blood sample). Samples should be collected by a qualified health care professional following routine precautions based on a point of care risk assessment and most up to date knowledge of the virus (see Routine Practices and Additional Precautions for Preventing the Transmission of Infection in Healthcare Settings.

Nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs

Nasopharyngeal swabs are the preferred specimens for respiratory virus testing, including A(H5N1) symptomatic or asymptomatic individuals. However, cases in Texas and California in 2024 with exposure to infected dairy cattle have had negative results on nasopharyngeal swab samples; oropharyngeal samples from the same patients tested positive for the virus. These findings emphasize the need for healthcare providers to be aware of potential limitations in testing techniques. This highlights the importance of considering multiple sampling methods for accurate diagnosis, particularly in cases of respiratory infections. The following respiratory specimens should be collected: (i) a nasopharyngeal swab, and (ii) combined nasal and oropharyngeal swabs (two separate samples combined after collection) Footnote 21. These samples would be collected using sterile swabs on Day 0, Day 7, Day 14 and Day 21 (or until a positive sample is produced, whichever comes first). Once collected, swabs should be placed into 2-3 mL of viral transport medium. The specimen can be split, with an aliquot of 1-2 mL sent to the National Microbiology Laboratory where confirmatory testing would occur on any RT-PCR positive sample(s) along with genomic analysis.

Conjunctival swab

Given that several human A(H5N1) cases identified in the United States have presented with conjunctivitis, we recommend referring individuals with symptoms of conjunctivitis (eye redness, swelling or discharge) that develop over the course of enhanced surveillance to public health for conjunctival sample collection and testing. Asymptomatic testing of conjunctival swabs is NOT recommended.

Use a flocked swab with a flexible shaft to sample the conjunctiva. Universal transport medium (UTM) or viral transport medium (VTM) should be used for specimen collection. The specimen can be split, with an aliquot of 1-2 mL sent to the National Microbiology Laboratory where confirmatory testing would occur on any PCR-positive sample along with genomic analysis.

Serum sample for serology

Blood samples will be collected for two purposes: to identify past exposure and to confirm active infection (versus nasal colonization) in a person that tested RT-PCR positive. A blood sample will be collected for all individuals on Day 0 - the start date of enhanced surveillance - and 21 days after initial collection via venipuncture. If an individual tests positive for A(H5N1) by RT-PCR, serum will be collected 21 days after the date of collection of the positive RT-PCR sample rather than at Day 21 of the enhanced surveillance. Samples should be collected by a trained phlebotomist.

Blood will be collected in either a serum (red top) or serum separator tube (SST), centrifuged and serum retrieved. We recommend collecting 7mL of blood, as a minimum of 1-2 mL of serum is required for testing.

Specimen storage and transport

Clinical specimens should be shipped in the appropriate packaging and according to the instructions of the receiving laboratory. Depending on the facilities available within a jurisdiction we recommend specimens' should be stored at 2-8°C following collection and should be transported to the provincial laboratory on ice packs within 72 hours of collection. Clinical specimens storage temperature depends on the duration of storage. If being stored for less than 7 days, specimens can remain at ≤-20°C (if storage needed for less than 7 days); if they will be stored longer than 7 days, they should be stored at ≤-70°C. Avoid freezing and thawing specimens because the viability of some viruses from specimens that were frozen and then thawed is diminished, shipping times should be minimized to prevent thawing. All specimens should be labeled clearly and include the information requested by the laboratory conducting the testing.

Transportation of dangerous goods

Shipping of specimens shall be done by a Transportation of dangerous goods (TDG)-certified individual in accordance with TDG regulations. For additional information regarding the classification of specimens for the purposes of shipping, consult either Part 2 Appendix 3 of the TDG Regulations or Section 3.6.2 of the International Air Transportation Association (IATA) Dangerous Goods Regulations as applicable.

Laboratory testing

RT-PCR

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is the most widely used method for detecting A(H5N1) due to its high sensitivity and specificity. RT-PCR will be performed on nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, and conjunctival (if collected) samples. All swabs should be tested separately. Influenza A RT-PCR should be the primary method for the detection of influenza. If the PCR specimen is positive for influenza A, subtyping with HA specific assays (i.e., H1, H3, H5, H7) should be performed. While subtyping should be attempted, if the viral load is low, subtyping may fail. Jurisdictions may also consider multiplex testing to assess co-infection or ruling in another non-influenza infection, like SARS-CoV-2.

Serology

To confirm infection, paired sera are collected Footnote 22 sample #1: collected first during the acute phase of illness and prior to infection (Day 0) and sample #2: 21 days or later after the onset of illness (or if negative RT-PCR and no symptoms on Day 21). Microneutralization is the recommended test for the measurement of antibodies to avian influenza, however hemagglutination inhibition assay (HI) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) may also be considered. Both samples should be tested simultaneously for the detection of influenza A(H5N1) antibodies in specimens from suspected human cases. Acute infection with A(H5N1) is confirmed when a fourfold or greater rise in antibody titre against A(H5N1) in paired sera (acute and convalescent) with the convalescent serum having a titre of 1:80 or higher is observed in a microneutralization assay. Prior infection with A(H5N1) is confirmed when an antibody titre of 1:80 or more in a single serum is detected along with a second positive result using a different serological assay (e.g. titre of 1:160 or greater in the HI assay using horse red blood cell or an A(H5) –specific western blot). It is essential that the A(H5) strain used in the assay be similar to the current circulating strain (e.g. CANADA - A/Texas/37/2024-like). Depending on when the enhanced surveillance is implemented the strain used may differ; we recommend reaching out to the National Microbiology Laboratory for recommendations and support when testing is required.

Genomic characterization

RNA will be extracted from positive nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs and the conjunctival swabs (as available) and used as template for next-generation sequencing. The obtained sequences should be compared to sequences from cattle, wild birds and poultry to determine the lineages of each gene segment and how closely related they are to the strain causing the animal outbreak. Sequence analysis should also be performed to assess for the presence of mutation(s) associated with mammalian adaptation or resistance to antivirals to meet Canada's International Health Regulations (IHR) obligations and the Nagoya protocol on access to genetic resources and benefit sharing. The National Microbiology Laboratory will be providing support and conducting genomic testing on the positive swab specimens submitted.

Statistical analysis and reporting of findings

Noting that the number of positive cases is likely to be small, it is recommended at minimum that summaries and descriptive statistics of the outbreak (including farm-level characteristics, demographics, case and non-case risk factors, and exposures) be calculated, if possible (please see Appendix 4 – Example analysis templates).

We recommend calculating:

- Cumulative incidence

- Overall (total number of cases (RT –PCR positive OR positive serology)/total number exposed)

- Asymptomatic (e.g. no clinical symptoms reported) (total number of asymptomatic cases (RT –PCR positive OR positive serology)/total number exposed)

- Symptomatic (total number of symptomatic cases (RT –PCR positive AND/OR positive serology)/total number exposed)

- Proportion of asymptomatic cases

- Total number of asymptomatic cases/total number of all cases

- Participation rate

- Total number of individuals tested/total number of eligible individuals identified

To address Objectives 2 and 4: we recommend pooled analyses of multiple sites. To measure risk factors for infection, the exposures and risk factors of cases (i.e., RT-PCR-positive or serology positive) versus non-cases (i.e., RT-PCR-negative or serology-negative) should be compared using appropriate statistical tests, e.g., Fisher's exact, t, and Kruskal Wallis tests. If sample sizes are sufficient, univariate statistical analysis and multivariate regression may be used to estimate the odds of infection associated with exposures and risk factors.

The following risk exposure categories can be used to assess individuals for Objectives 2 and 3. These have been adapted from the exposure risk groups in the guidance on human health issues related to avian influenza in Canada (HHAI), exposure risk levels in the Public health management of human cases of avian influenza and associated human contacts (AI CCM), and what is currently known about exposures and human cases of A(H5N1) as of fall, 2024. The exposure-risk categories are not limited to the descriptions below, other situations may apply and should be assessed on a case-by-case basis:

High risk of exposure

- Exposure to a healthy, sick or dead animal, or animal secretions, excretions, products, and byproducts, that tested positive for A(H5N1) with no or inconsistent PPE use or a PPE breach

- Exposure to a sick or dead animal, or animal secretions, excretions, products and byproducts, of the same species that tested positive for A(H5N1), with no or inconsistent PPE use (responded "sometimes" or "never") or a PPE breach

- Exposure to a confirmed human case of A(H5N1) or contact with items and surfaces contaminated with their bodily fluids with no PPE

Moderate risk of exposure

- Exposure to a healthy animal of the same species as those that tested positive for A(H5N1), with no or inconsistent PPE use (used "sometimes" or "never") or a PPE breach

- Exposure to sick or dead animals on the farm of a species that has not tested positive for A(H5N1), with no or inconsistent PPE use (used "sometimes" or "never") or a PPE breach

- Exposure to a human case of A(H5N1) without proper or adequate PPE

Low risk of exposure

- Exposure to healthy animals on the farm of a species that has not tested positive for A(H5N1), with or without PPE use

- Exposure to healthy animals of the same species as tested positive for A(H5N1), if adequate and proper PPE is always used

- Exposure to sick or dead animals on the farm of a species that has not tested positive for A(H5N1), if adequate and proper PPE is always used

- Limited exposure to a human case of A(H5N1) with proper PPE

Data management

We recommend that the implementation team develops a Data Management Plan that specifies how the data will be collected, housed, combined, linked, anonymized, de-identified, aggregated, prepared, analysed and safeguarded.

Ethical considerations

PHAC consulted with the Public Health Agency of Canada's Public Health Ethics Consultative Group (PHECG) during the development of this protocol. They highlighted several considerations which have been summarized in this section and which should be considered during enhanced surveillance implementation.

Ethics approval

Depending on which Canadian jurisdiction is implementing this protocol, there may be differences with respect to whether the activity is considered research and therefore whether it requires a Research Ethics Board Review. It is recommended that jurisdictions seek local review of this protocol through appropriate governance mechanisms in anticipation of its implementation. The CDC has stated that similar activities (including sera collection) were being conducted as part of public health response and thus not considered research Footnote 23.

Equity

As with other infections, avian influenza may have a greater impact on certain population groups, in terms of those exposed and illness experienced (e.g., duration, severity), due to social, economic, health, and other risk factors (i.e., older age, chronic medical condition, poverty, living in a remote and isolated community or crowded setting).

Public Health Authorities should consider health equity and psychosocial implications when considering enhanced surveillance and the impact on individuals and farms. An individual's ability and willingness to participate or to practice recommended public health measures, including isolation and quarantine, may be impacted by a range of factors, including:

- Social and economic challenges, such as inflexible working conditions, employment or housing instability, food insecurity, domestic violence or abuse

- Individual skills, abilities and vulnerabilities, such as:

- Reading, speaking, comprehension or communication barriers

- Physical or psychological difficulty in undertaking public health measures

- Need for assistance with personal or medical care activities or supplies

- Need for ongoing supervision

- Social or geographic isolation, such as:

- Insufficient family, friends, or community resources for support

- Residence in an area with limited services or supports, including telecommunications and for mental health and addictions

- Limited availability of and access to plain-language and multilingual guidance

- Limited availability of and access to personal protective equipment and supplies

Public health messaging should be clear, consistent, and sensitive to the needs of populations with social, economic, cultural, or other vulnerabilities.

First Nations, Inuit, and Métis

Outbreaks or cases may be identified on First Nations, Inuit, Métis, land, farms or communities. Engagement with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis to adapt this protocol in advance of implementation is imperative to ensure the processes outlined here are conducted in partnership with Indigenous peoples and reflect flexibility, cultural humility, and recognition of the distinct nature and lived experience of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.

Informed consent and assent

Standard practice should be followed with considerations for transparency about the purpose of testing, potential discomfort in sample collection, self-isolation requirements, and data handling practices.

The following risks and benefits may be discussed with all exposed individuals:

- Transparency about the purpose of enhanced surveillance. The enhanced surveillance outlined here supports the detection of missed cases of avian influenza, allowing for the detection of any genetic changes in the virus that pose an increased risk to human health. The information collected may also help determine which types of exposures in farm settings are associated with an increased risk of infection. Public health can use this information to manage the outbreak and update guidance around measures that reduce the risk of human infection.

- Acknowledgement of potential discomfort during sample collection. Sample collection may cause discomfort for individuals including those associated with venipuncture, nasopharyngeal and conjunctival swabs which may cause temporary discomfort at the procedure sites.

- Risk of self-isolation. Anyone tested as part of enhanced surveillance, even individuals who are without symptoms may receive a positive test result. Depending on the jurisdiction public health contact management protocols may require positive individuals to isolate from animals and other individuals for up to 14 days (including household contacts). Knowing one's infection status can protect others by preventing onward transmission (however human to human transmission is incredibly rare). Having to isolate may impact farm operations and a coverage plan to ensure continuity of work might be required.

- Confidential handling of data and information. Confidentiality of questionnaire responses and test results will be maintained to the full extent legally possible. Summary information that does not identify an individual may be shared with the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and the provincial and territorial ministries of agriculture as part of a One Health approach to outbreak investigation that considers the joint health of people, animals and the environment. Data will be destroyed according to provincial, territorial and federal data retention schedules.

Increasing awareness and reducing stigma associated with A(H5N1)

Everyone on the farm premises, should be provided with general information about A(H5N1), including what is known about transmission and prevention, symptoms, clinical outcomes, and treatment to increase awareness and minimize the risk of stigmatization if individuals do become infected.

Considerations for incentives

Incentives for testing might be considered. Participants in similar public health surveillance activities designed by the US CDC are offered VISA gift cards up to a maximum amount of $75 $25 for completing the questionnaire, and $25 each for a blood sample and nasopharyngeal swab). On-site sample collection or pre-arrangements for travel to sample collection sites might reduce barriers to testing, but care should be taken to ensure they are not seen to be coercive. Consideration could be given to reimbursement of costs associated with travel for specimen collection.

Considerations for self-isolation

Compensation might be considered for those who test positive (via RT-PCR). This could include consideration of lost wages and the cost of hotel accommodation if isolation is not feasible on-farm due to congregate living arrangements. We recommend developing local plans to respond to isolation needs particularly where workers are living together, or in remote areas with insufficient space to isolate. This has been identified as an issue in dairy farm H5N1 outbreaks in the United States Footnote 24 and for temporary foreign workers in Canada during COVID-19 outbreaks Footnote 25.

Prevention of HPAI in investigation personnel

Front-line staff should be trained in infection control procedures based on their roles in the investigation not only to minimize their own risk of infection when in close contact with individuals during home visits and elsewhere, but also to minimize the risk of the investigation personnel acting as a vector of infection between individuals on or between farms.

Consider: option to provide seasonal influenza vaccination to the front-line staff depending on the genetic and antigenic characteristics of the new strain and to prevent co-infection.

Consider: Depending on the transmissibility and severity of the new strain, stricter infection control procedures among the front-line staff may be required.

Reporting obligations

Cases and individuals exposed

Individuals will be notified of the results of their RT-PCR tests. If positive, individuals will be connected with appropriate public health authority who will lead case and contact management. Standard practice includes medical follow-up, clear instructions and isolation requirements, information on A(H5N1), and case and contact management (which may include oseltamivir). Results of serology will take longer to process and depending on the nature of the analysis individuals will be consulted on whether they would like to receive an interpretation of their individual lab results.

Local public health

Any persons under investigation, probable or confirmed cases found because of the enhanced surveillance will be reported to local public health authorities. Provincial and territorial public health authorities are obligated to report probable and confirmed cases regardless of severity to PHAC within 24 hours of their own notification via the Emerging respiratory pathogens and Severe Acute Respiratory Infection (SARI) case report form. Established inter-jurisdictional notification processes would apply if exposures occurred in another jurisdiction, the case was identified in another jurisdiction, the case travelled between jurisdictions during their communicable period, or contacts reside in a different jurisdiction than does the case.

International bodies

PHAC acts as the International Health Regulations (IHR) national focal point, which is the national centre designated to communicate with the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) on the Canadian situation. PHAC must notify the WHO, within 24 hours of assessment of public health information, of any event related to a human case of avian influenza under Article 6 of the WHO's International Health Regulations (2005).

Detailed roles and responsibilities of federal, provincial, territorial and local stakeholders can be found in the roles and responsibilities section of the guidance on human health issues related to avian influenza in Canada (HHAI).

References

- Footnote 1

-

WHO (2021). Cumulative number of confirmed human cases for avian influenza A(H5N1) reported to WHO, 2003-2021, 15 April 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/cumulative-number-of-confirmed-human-cases-for-avian-influenza-a(h5n1)-reported-to-who-2003-2021-15-april-2021

- Footnote 2

-

CDC (2024). Technical Report: June 2024 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Viruses. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/php/technical-report/h5n1-06052024.html WHO (2021).

- Footnote 3

-

CDC(2024). CDC Confirms Human Cases of H5 Bird Flu Among Colorado Poultry Workers https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/p-0715-confirm-h5.html

- Footnote 4

-

CDC (2024). Technical Update: Summary Analysis of Genetic Sequences of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Viruses in Texas. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/spotlights/h5n1-analysis-texas.html

- Footnote 5

-

Peiris, J. M., De Jong, M. D., & Guan, Y. (2007). Avian influenza virus (H5N1): a threat to human health. Clinical microbiology reviews, 20(2), 243-267.

- Footnote 6

-

Public Health Agency of Canada (2024). Pandemic risk scenario analysis update: Influenza A(H5Nx) clade 2.3.4.4b virus and related future novel viruses. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/emergency-preparedness-response/rapid-risk-assessments-public-health-professionals/update-pandemic-risk-scenario-analysis-influenza-a-h5nx-clade-2-3-4-4b-virus-related-future-novel-viruses.html

- Footnote 7

-

Morris, S. E., Gilmer, M., Threlkel, R., Brammer, L., Budd, A. P., Iuliano, A. D., et Biggerstaff, M. (2024). Detection of novel influenza viruses through community and healthcare testing: Implications for surveillance efforts in the United States. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses, 18(5), e13315.

- Footnote 8

-

Shittu, I., Silva, D., Oguzie, J.U., Marushchak, L.V., Olinger, G.G., Lednicky, J.A., Trujillo-Vargas, C.M., Schneider, N.E., Hao, H. and Gray, G.C., (2024). (2024) A One Health Investigation into H5N1 Avian Influenza Virus Epizootics on Two Dairy Farms. Preprint. medRxiv. org/content/10.1101/2024.07.27.24310982v1.full.pdf

- Footnote 9

-

WHO (2024). Emergency response framework (ERF), Edition 2.1 https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240058064

- Footnote 10

-

Statistics Canada (2021). Dictionary, Census of Population, 2021 – Census farm. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/ref/dict/az/definition-eng.cfm?ID=pop012

- Footnote 11

-

Canadian Food Inspection Agency (2024). Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in cattle: Guidance for private veterinarians. https://inspection.canada.ca/en/animal-health/terrestrial-animals/diseases/reportable/avian-influenza/latest-bird-flu-situation/hpia-livestock/hpai-cattle-guidance

- Footnote 12

-

Uyeki, T. M. (2009). Human infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus: review of clinical issues. Clinical infectious diseases, 49(2), 279-290.

- Footnote 13

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2020). Flu (influenza): Symptoms and treatment. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/flu-influenza.html

- Footnote 14

-

Caserta, L.C., Frye, E.A., Butt, S.L., Laverack, M., Nooruzzaman, M., Covaleda, L.M., Thompson, A.C., Koscielny, M.P., Cronk, B., Johnson, A. and Kleinhenz, K. (2024). Spillover of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus to dairy cattle. Nature 634, 669-676.

- Footnote 15

-

CDC (2024). Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus in Animals: Interim Recommendations for Prevention, Monitoring, and Public Health Investigations. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/prevention/hpai-interim-recommendations.html

- Footnote 16

-

CDC (2022). Case Definitions for Investigations of Human Infection with Avian Influenza A Viruses in the United States (cdc.gov). https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/hcp/case-definition/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/case-definitions.html

- Footnote 17

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2013). Severe Acute Respiratory Infection (SARI) Case Definition. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/emerging-respiratory-pathogens/severe-acute-respiratory-infection-sari-case-definition.html

- Footnote 18

-

Kurmi, B., Murugkar, H. V., Nagarajan, S., Tosh, C., Dubey, S. C., & Kumar, M. (2013). Survivability of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus in poultry faeces at different temperatures. Indian Journal of Virology, 24(2), 272-277.

- Footnote 19

-

PHAC (2021). Flu (influenza): FluWatch surveillance. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/flu-influenza/influenza-surveillance.html

- Footnote 20

-

WHO, (2005). Writing Committee of the World Health Organization (WHO) Consultation on Human Influenza A/H5. Avian influenza A (H5N1) infection in humans. New England Journal of Medicine, 353(13), 1374-1385.

- Footnote 21

-

CDC (2024). Interim Guidance on Specimen Collection and Testing for Patients with Suspected Infection with Novel Influenza A Viruses Associated with Severe Disease or with the Potential to Cause Severe Disease in Humans. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/php/severe-potential/index.html

- Footnote 22

-

WHO (2007). Recommendations and laboratory procedures for detection of avian influenza A(H5N1) virus in specimens from suspected human cases. https://www3.paho.org/hq/images/stories/AD/HSD/CD/INFLUENZA/recailabtestsaug07.pdf

- Footnote 23

-

Kniss, K., Sumner, K. M., Tastad, K. J., Lewis, N. M., Jansen, L., Julian, D.,... & Fry, A. (2023). Risk for infection in humans after exposure to birds infected with highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus, United States, 2022. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 29(6), 1215.

- Footnote 24

-

NPR (2024). Bird flu cases among farm workers may be going undetected, a study suggests. https://www.npr.org/sections/shots-health-news/2024/07/31/nx-s1-5059071/bird-flu-human-cases-farm-workers-testing

- Footnote 25

-

Landry, V., Semsar-Kazerooni, K., Tjong, J., Alj, A., Darnley, A., Lipp, R. and Guberman, G.I. (2021). The systemized exploitation of temporary migrant agricultural workers in Canada: Exacerbation of health vulnerabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic and recommendations for the future. Journal of Migration and Health, 3.

Acknowledgements

We thank the many partners involved in developing this guidance. We thank the internal technical working group members that met, contributed to and reviewed this guidance: Dr. Catherine Elliot, Laura MacDougall, Dr. Kaitlin Patterson, Heather Rilkoff, Dr. Eleni Galanis, Dr. Nicole Atchessi, Dr. Christina Bancej, Dr. Natalie Bastien, Dr. Peter Buck, Dr. Sharon Calvin, Dr. Taeyo Chestley, Sabrina Chung, Fanie Lalonde, Dr. Daniella Rizzo, Amanda Shane, and Dr. Clarence Tam.

Thank you to the individual investigators and organizations for sharing similar protocols and experiences to assist in the development of this guidance:

- Danuta Skowronski, BCCDC (H7N3 protocol)

- Ben Cowling, WHO - CONCISE protocols

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – Michigan H5N1 surveillance protocol

- Richard Puleston, UK – Asymptomatic Avian Influenza Surveillance study

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency – Premises investigation questionnaire (PIQ)

We thank the PHAC the Public Health Agency of Canada's Public Health Ethics Consultative Group (PHECG) that provided recommendations on the ethical considerations for the implementation of this guidance. We thank the following members of CERIPP that provided feedback: Toju Ogunremi, Gagan Tathgur, Gisele Belliveau-Gould, Zoe Regalado, Aline Karrass, Suruthi Senthilvel, Dr. Mireille Plamondon, and Nicole Pachal.

We also thank the following external reviewers for their feedback and recommendations on this guidance: Dr. Isabelle Meunier (QC), Dr. Caroline Huot (QC), Dr. Manon Racicot (CFIA), Dr. Jamie Imada (CFIA), Dr. Noel Harrington (CFIA), Dr. Cathy Furness (CFIA), Dr. Carole Kurbis (MB), Dr. Yong Lin (NS), Linda Passerini (NS), Aini Khan (NS), Katie McIsaac (NS), Dr. Hollyn Maloney (AB), Dr. Michelle Murti (ON), Dr. Katherine Paphitis (ON), Dr. Richard Mather (ON), Dr. Heather McClinchey (ON), Jennifer Pritchard (ON)

Contact us

To request sample downloadable questionnaires or templates, please contact Horizontal Surveillance Operations at Horizontal Surveillance Operations (PHAC): HSO-OSH@phac-aspc.gc.ca

Page details

- Date modified: