Chapter 2 - Understanding of Sexual Misconduct

This chapter provides an overview and guidance for CAF members and leadership teams on understanding and recognizing the signs of sexual misconduct, and its impact on individuals, units and the team.

SPECTRUM OF SEXUAL MISCONDUCT

The spectrum of sexual misconduct conceptually represents the range of attitudes, beliefs, and actions that contribute to a toxic work environment. The negative behaviours span from unacceptable conduct in the yellow to Criminal Code violations in the red; even behaviours in the yellow zone could result in a charge under the Code of Service Discipline.

Figure 2: The spectrum of sexual misconduct

Text version

Not remaining in the green zone may result in administrative actions, disciplinary actions or both.

Leadership has a mandate to create and/or maintain the conditions so behaviour stays in the green zone

Where is the line?

There is a spectrum of unacceptable conduct and behaviours, this slide shows that all these inappropriate behaviors can lead to a service offence. Every instance will be addressed by the CoC.

The line is very clear… stay in the green!

Any of these inappropriate behaviours may lead to a toxic work environment.

A toxic work environment occurs when people’s behaviours make other people feel excluded, isolated and even have concerns for their safety.

Note: The placement of items in the Toxic Environment zone is for conceptual purposes to show there is a spectrum with increasing seriousness and those on the far right, in the red zone tend to be criminal.

The placements do not convey any value judgement, [[particularly as each type of issue may have a spectrum of its own.]]

CONSENT

MYTH:

If it's a sexual assault, it means that someone was beaten.

Myth: It’s only sexual assault if there was penetration and if the survivor was beaten and bleeding, or they were threatened with a weapon.

Fact: According to the Criminal Code, sexual assault is any sexual activity without consent, regardless of whether there are physical injuries or a weapon used.

- 2.0. In the context of sexual misconduct, consent is the voluntary and ongoing agreement to engage in sexual activity that is granted without the influence of force, threats, fear, fraud or abuse of authority.[1]

- 2.1. Questions regarding consent can arise in the context of relationships where there is a power imbalance. Accordingly personal relationships where the individuals involved are of a different rank could be considered adverse, unless the relationship is properly disclosed IAW DAOD 5019-1 Personal Relationships and Fraternization.

- 2.2. The CAF respects the right of individuals to form personal relationships IAW DAOD 5019-1 Personal Relationships and Fraternization. However, if a personal relationship, particularly one not declared to the chain of command, involves differences in rank, authority, and power it calls into question the consensual nature of the relationship.

- 2.3. Silence should not be interpreted as consent. Consent can be revoked at any time and can be in question if the victim is intoxicated. Consent cannot:

- be assumed;

- be given if unconscious;

- be obtained through threats or coercion; and

- be obtained if the perpetrator abuses a position of trust, power, or authority.

- 2.4. Consenting to one kind or instance of sexual activity does not mean that consent is given to any other sexual activity or instance. Consent can be withdrawn at any time, even after sexual activity has been initiated.

- 2.5. While not limiting the circumstances, section 273.1 of the Criminal Code sets out when there is no consent:

- where the agreement is expressed by the words or conduct of a person other than the complainant [individual];

- where the complainant [individual] is incapable of consenting to the activity;[2]

- where the accused induces the complainant [individual] to engage in the activity by abusing a position of trust, power or authority;

- where the complainant [individual] expresses, by words or conduct, a lack of agreement to engage in the activity; or

- where the complainant [individual], having consented to engage in sexual activity, expresses, by words or conduct, a lack of agreement to continue to engage in the activity.[3]

EXAMPLES OF WHAT CAN CONSTITUTE SEXUAL HARASSMENT

- 2.6. The following examples are not exhaustive, but should help identify what may be considered sexually harassing behaviour:

- Sexual advances which may or may not be accompanied by threats or explicit or implicit promises;

- Making rude, sexually degrading or offensive remarks or gestures;

- Engaging in reprisals for having made a complaint of sexual harassment;

- Discrediting, ridiculing, or humiliating an individual by spreading malicious gossip or rumours of a sexual nature;

- Questions, suggestions or remarks about a person's sex life.

- Sexual or sexually suggestive name calling in private or in front of others; and

- Belittling a person by making fun of their sex, sexuality, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression (as described in Canadian Human Rights Act).

- Placing a condition of a sexual nature on employment or on any career opportunity including but not limited to training or promotion;

- Displaying pictures, posters, or sending e-mails that are of a sexual nature; and

- Unwelcome social invitations, with sexual overtones or flirting, especially when there is a rank or power differential between the individuals involved.

- 2.7. For examples of what does and does not constitute sexual harassment, refer to the Tool to Guide Employees on the Government of Canada website.

- 2.8. For guidance on what to do if you or someone else is being sexually harassed, refer to HOW TO RESPOND TO SEXUAL MISCONDUCT in Chapter 3.

THE IMPACT

- 2.9. Trauma for victims of sexual misconduct is individual; directly after an incident, there is often shock. When a victim knows the alleged offender, there can be guilt and self-doubt. The emotional damage can emerge immediately after or take time to appear, and can include anxiety, long-term insomnia, a sense of alienation and thoughts of suicide. While some victims may experience hyper-vigilance, others may start taking risks and turning to harmful coping strategies. The trauma of sexual assault can impact victims for a lifetime, affecting their health, education and careers. However, with proper care and social support, victims can recover and grow beyond the incident.

- 2.10. In the case of sexual assault, the brain interprets this as a threat to survival, and responds accordingly to protect the individual. This is not a conscious choice. Physiological reactions can include what is commonly described as, “fight, flight, or freeze”. Furthermore, sexual responses during assault may occur, which can be confusing and horrifying to the individual. Depending on the body’s reaction at the time of the event, this could influence how the person interprets their experience and be a factor in their recovery.[4]

IMPACTS ON VICTIMS

- 2.11. The short and long-term impacts of sexual misconduct may include (not an exhaustive list):[5]

- Feeling afraid to leave home/go to work or fearing people in general. The process of restoring self-confidence is particularly difficult if the victim was targeted by someone they trusted, respected, or loved. In this case, their faith and trust in others, in the world and in their own judgment may also be threatened;

- Guilt. Feelings of guilt and self-blame may affect the decision to seek help. Some people may feel that the victim is to blame for being targeted, and that they provoked the incident(s) through their appearance or behaviour. Victims may also feel responsible for ‘not knowing any better’ or not paying attention to “gut instincts” they may have had. They may not even identify what was happening as sexual misconduct;

- Shame. The destruction of self-respect, the deliberate efforts by the attacker to humiliate them, or make them do things against their will, may make the victim feel dirty, disgusted by the assault, and ashamed. That they “allowed” the incident(s) to happen at all may also make them feel ashamed. Feelings of shame may make them reluctant to report the crime to the police or to reach out for help. Because of their own actions (e.g. partying, drinking) they may believe others will blame them. They may also believe their previous sexual experiences will be scrutinized;

- Loss of control over their life. A victim may have believed they would be able to resist, or that they could defend themselves from a sexual assault. If the attacker overcame their resistance by coercion, force or fear, they may no longer feel confident about themselves or their ability to stand up for themselves;

- Shock, feeling disoriented or out of touch with reality. Many people may go through a period of numbness, disbelief or denial, feeling detached from their lives etc. Some people may appear unemotional or speak of the event in a matter-of-fact way. They may feel a degree of separation from their everyday life, as though it does not quite feel real.

- Intrusive Memories, Flashbacks and Re-experiencing: Intrusive memories of the sexual assault can interfere with a person’s day-to-day functioning, negatively impacting their mood and cognitive capacity. Some will re-experience memories of their assault with a magnitude beyond the intrusion of unwanted negative memories. They may feel as though the assault is happening in the present; they feel as though they are back at the time the sexual assault occurred. The re-experiencing of the assault involving full physical and emotional response is called a flashback. Flashbacks can be extremely disruptive to a person’s life, often making them feel like they have little control over their own thoughts, feelings and physical reactions.

- Embarrassment. It is often normal for victims to feel embarrassed. If there was a sexual assault, the attacker may have used offensive sexual language. The victim may be uncomfortable or embarrassed to say these words in recounting the assault. If the sexual assault involved sexual acts that they may perceive as being “deviant”, they may have a harder time finding the words to describe what has happened to them. A medical exam can feel like another form of violation. Their body is again exposed and is an object of attention and inspection by strangers. They may be too embarrassed to admit their uneasiness and discomfort during the exam. The person may benefit from additional support during this procedure;

- Incomplete memories of the incident or periods of time since the incident(s). Stress hormones released during traumatic experiences can affect the creation and consolidation of memories, making it hard to recall chronological details of the event. It’s like putting together a puzzle without all of the pieces. The use of alcohol and drugs can further impair this function;

- Use of intoxicants. Drinking too much alcohol, taking more drugs than prescribed, or using illegal drugs may be an affected person’s way to cope;

- Anger. They may be angry at themselves, the perpetrator and/or the situation in general. This is common, and victims require compassion as they work through the aftermath of their experience. The person can appear more reactive or agitated, which can have an influence in various aspects of their life, including their social relationships (people react to their reactivity). Anger can affect one’s outlook on life and be communicated in many different ways;

- Wondering - why me? Some people wonder why the alleged offender chose them. These feelings arise from the common misconception that people “ask for it,” or in some other way made themselves vulnerable;

- Changes in intimate relationship functioning. Examples include increased isolation, decreased desire for sexual intimacy or increase in risky sexual behaviours;

- Increased symptoms of a pre-existingcondition;

- Concern for the perpetrator. If the attacker was someone the victim knew or cared about, they may express concern about what will happen if they report the attack to the police and may feel guilty reporting the crime. Some victims prefer that the perpetrator receives counselling rather than jail time;

- Work and/or career implications. In the short-term, affected persons of sexual violence in the workplace often talk of feeling sick to their stomach going in to work, and having anxiety, and panic attacks at work. They may have trouble paying attention and staying focused on a task, they may participate less in group meetings or skip them all together. They may avoid going to work or think about quitting work completely. Their current behaviour at work can negatively influence their interest or ability to seek career advancement; and

- Impacts on quality of life, work loss, and criminal justice costs. In a qualitative study of sexual violence survivors, research has shown that sexual violence and the trauma resulting from it can have an impact on the survivor’s employment in terms of time off from work, diminished performance, job loss, or being unable to work.[6]

- 2.12. Many of the impacts described above can be reasons why affected persons may hesitate to come forward. The Tool “Why it may be difficult to disclose” discusses this subject in more depth.

FACT:

In Canada, the vast majority of reported sexual assaults are committed by someone close to the victim.

In most cases of sexual assault, the offender is known to the victim–a supervisor, co-worker, friend, boyfriend, girlfriend, spouse, neighbour, or relative.

In 2007, police forces reported that in 82% of sexual assaults the victim knew the perpetrator.

· 31% of accused were family members;

· 28% were casual acquaintances;

· 8% were identified as friends;

· 6% were identified as authority figures; and,

· 5% were current or former boyfriends/girlfriends.

Source:

http://www.calgarycasa.com/resources/sexual-assault-myths-and-facts/ (Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, 2009) (Statistics Canada (2010), The Nature of Sexual Offences)

Myth: If someone were sexually assaulted, they wouldn’t be talking to the perpetrator the next day.

Fact: There are many reasons why a victim might maintain a relationship with someone who has assaulted them.

The victim might feel their safety would be threatened if they ended the relationship.

The victim may be unable to avoid the perpetrator if they live together, work together, are in class together, or have the same social circles.

Or the victim might still be defining and trying to understand what’s happened to them.

Victims often feel social pressure to act like everything is okay, regardless of how they actually feel.

The important thing to remember is that people cope with traumatic incidents in different ways.

IMPACTS ON THE UNIT

- 2.13. The impacts of unaddressed sexual misconduct in a unit can lead to:

- increased absenteeism,

- deteriorating relationships among coworkers,

- lack of unit cohesion,

- reduced morale,

- loss of trust in the leadership, and

- a negative effect on mission effectiveness. [7], [8]

- 2.14. If the alleged offender is from the same unit as the affected person, the unit can become polarized as members often feel compelled to choose sides. Even if the perpetrator is not from the unit, unit cohesion may still suffer if members perceive that the chain of command is not doing its job.

- 2.15. The impacts of sexual misconduct are far-ranging and affect many people. This can include friends and family, members of the chain of command, as well as those who support affected persons.

IMPACTS ON THE CAF

- 2.16. Sexual misconduct which remains unaddressed can have the following impacts on the CAF:

- the perception that victims and their well-being are not a priority for the CAF;

- the perception that aggressors can act with some degree of impunity;

- lack of trust in the chain of command; and

- the loss of valued personnel when they leave the CAF prematurely due to sexual misconduct.

Myth: Tough men don’t get sexually assaulted.

Fact: A man’s physical strength does not necessarily protect him from being assaulted.

A sexual assault can be committed through coercion or manipulation, can involve objects, or can be drug- or alcohol-facilitated.

- 2.17. Sexual misconduct undermines the CAF’s institutional credibility by eroding Canadian society’s confidence in its ability to deliver results on its behalf.

MEN AS SURVIVORS OF SEXUAL ASSAULT

- 2.18. Men may face some unique challenges following an experience of sexual trauma.[9] Men are often less willing to seek support, and may feel isolated, alienated from others, and emotionally vulnerable.

- 2.19. According to research on sexual assault and sexual harassment in the United States military, many sexual assaults of men involve more than one attacker, weapons, or forced participation—even when no immediate physical assault or force was involved. Relative to women, men are more likely to experience multiple incidents of sexual assault, during duty hours or at their duty station, where alcohol is not necessarily a factor. Most of those sexual assaults go unreported because men are more likely to identify it as a hazing event – they simply do not think of it as a sexual assault.[10]

- 2.20. For men, sexual assault may trigger negative self-judgments and cause them to question their masculinity.

- 2.21. Male victims of sexual assault may contend with issues of:

- Legitimacy (“Men can’t be sexually assaulted”, “No one will believe me”);

- Masculinity (“I must not be a real man if I let this happen to me”; “My manhood has been stolen”);

- Strength and power (“I should have been able to fend him/her/them off”; “I shouldn’t have let this happen”); and

- Sexual identity (“Am I gay?”; “Will others think I’m gay and only pretended not to like it?”).

WOMEN AS SURVIVORS OF SEXUAL ASSAULT

MYTH:

Young, physically attractive women are assaulted because of how they look.

Myth: Young, physically attractive women are assaulted because of how they look, or because they dress provocatively, are out alone at night or have been drinking a lot.

Fact: The belief that only young, pretty women are sexually assaulted stems from the myth that sexual assault is based on sex and physical attraction.

Women of all ages and appearances, and of all classes, cultures, abilities, sexualities, races and religions are sexually assaulted.

What a woman was wearing when she was sexually assaulted or how she behaved is irrelevant.

- 2.22. According to research on sexual assault and sexual harassment in the United States military, women survivors of sexual trauma in the military face unique challenges.[11] Because there are fewer women than men in the military, a woman may feel the need to prove herself; she may worry that others will see her as weak if she speaks up. She may fear that others may think she is just causing trouble or undermining the group’s strength. Women survivors may also worry that speaking up will damage unit morale, especially if their attacker is a co-worker or fellow service member; they may worry that coming forward will interfere with social opportunities and career advancement.

MEMBERS OF THE LGBTQ2+ COMMUNITY AS SURVIVORS OF

SEXUAL ASSAULT

- 2.23. For LGBTQ2+ survivors of sexual assault, their identities – and the discrimination they face surrounding those identities – sometimes make them hesitant to seek help from police, hospitals, shelters or sexual assault centers, the very resources that are supposed to help them.

VICTIM-BLAMING

WHAT IS VICTIM-BLAMING?

- 2.24. A person who wonders how the victim of a crime could have behaved differently or made different choices to avoid what happened can be said to be engaging in some degree of victim-blaming. Questioning what a victim could have done differently in order to prevent a crime from happening can imply that the fault of the crime lies with the victim rather than the perpetrator.[12]

- 2.25. Examples of victim-blaming might include suggestions that an individual was sexually assaulted because they traveled through a “bad” neighbourhood, or somehow invited/allowed a sexual assault to happen by wearing provocative clothing or getting too intoxicated.

MYTH:

“I am careful–that would never have happened to me.”

Myth: Most victims of sexual assault can prevent the assault from taking place by resisting.

Fact – Assailants commonly overpower victims through threats and intimidation tactics.

A person might not fight back for any number of reasons, including fear or incapacitation.

Silence or the absence of resistance does not mean that the victim is giving consent.

- 2.26. Victim-blaming is sometimes subtler, and people may participate in it without intending to blame the victim and may not even realize that they are doing it. A person who hears about an assault and thinks, “I would have been more careful,” or “That would never happen to me,” for example, is blaming the victim on some level, often unintentionally.

- 2.27. The following are examples of victim-blaming comments:

- "Did you do anything that could have been misunderstood?"

Some people may think sexual assault is just a result of miscommunication, especially if they know the attacker and have trouble believing that they could do something like that.

- "Were they drinking?”

This question is often a euphemism for "Did you make yourself more vulnerable to sexual assault by drinking?" An analogy would be to criticize someone for being in a car accident where another driver was entirely responsible for the accident.

- "Why did he/she stay with her/him?"

This is frequently said of victims of domestic violence who weren't able to leave their abusers. Often, victims don't acknowledge that they are being abused because their abusers teach them it is normal, and sometimes getting out of an abusive relationship is riskier than staying in it because victims don't have a safe place to go.

WHY DO PEOPLE BLAME VICTIMS?

- 2.28. Victim-blaming is a common reaction to crime.[13] The idea that bad things can randomly happen to good people who do not deserve them is frightening to many, as it suggests that anyone could become a victim at any time. In order to protect against this fear, people may develop an idea that the world is a fair and just place, subscribing to a psychological phenomenon known as the “just world hypothesis”.[14] This ideology allows people to believe the victim of a crime bears responsibility for that crime, an erroneous belief that nonetheless may often allow people to feel comforted, as they can then tell themselves, “If I’m careful, that will never happen to me.” In this way, victim-blaming can be a form of self-protection.

VICTIM-BLAMING IN THE MILITARY

- 2.29. Competing loyalties can lead to victim-blaming when a CAF member has been the victim of another CAF member’s sexual misconduct. Other members of the unit may be torn between support and compassion for the victim and loyalty to the alleged offender and/or the unit, especially if the alleged offender is perceived to be a valuable member of the team. It may be implied, whether overtly or in more subtle ways that the victim is to be blamed for undermining unit morale and hurting the team.

- 2.30. Victim-blaming in a military unit, if not addressed, can lead to retaliation in the form of a reprisal, ostracism, or maltreatment, one of the main reasons that victims can be reluctant to come forward.

HOW CAN VICTIM-BLAMING AFFECT VICTIMS?

- 2.31. Many people who have been the victim of a crime will experience some degree of self-blame and shame. Victim-blaming can perpetuate those feelings of shame and also decrease the likelihood of a victim seeking help and support, due to fear of being further shamed or judged for their “role” in the crime or attack.

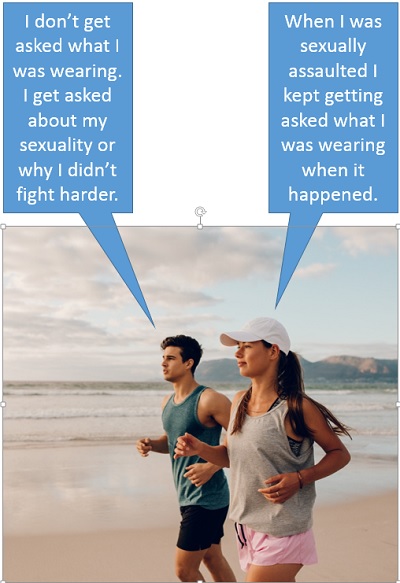

Figure 3: Victim-blaming

Text version

I don’t get asked what I was wearing. I get asked about my sexuality or why I didn’t fight harder.

When I was sexually assaulted I kept getting asked what I was wearing when it happened.

- 2.32. Being a victim of crime is likely to be traumatic in itself. Being blamed for the crime, even subtly or unconsciously, may lead a person to feel as if they are under attack once again. This can lead to increased depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress.

- 2.33. Victim-blaming may also prevent people from reporting the crime. Victims of a crime may hesitate to report the issue, for fear of being blamed, judged, or not believed.

HOW TO AVOID VICTIM-BLAMING

- 2.34. When speaking with someone who has been sexually assaulted, it may be helpful to avoid asking too many questions about the event to avoid giving an impression of blaming the victim. An individual who already feels ashamed may be more likely to interpret “why” questions as a kind of blame.

- 2.35. Simply offering compassion to the victim and listening to what they have to say without offering judgments or interpretations of the event may be the best way to show support.[15]

- 2.36. For more guidance on how to provide a supportive response to a victim of sexual misconduct, refer to Chapter 4 – SUPPORT.

RETALIATION

- 2.37. While growing numbers of affected persons are making the difficult choice to report sexual assault, some are subjected to retaliation.

- 2.38. Retaliation can come in the form of a reprisal, ostracism, or maltreatment. The propagation of rumours about a sexual assault case can often lead to retaliation, which is a deterrent to reporting.[16]

- 2.39.Sometimes retaliation is unintentional; someone is ignored and excluded from group activities because others feel awkward around them following an incident or a report. Well-intentioned team members may also exclude affected persons intending to give them personal space to recover, but this can be perceived as retaliation by the affected person.

- 2.40. Chapter 3 discusses the prohibition on reprisals, and provides guidance on reporting allegations of reprisals.

[2] For example, intoxicated, mentally incapacitated, and under the age of consent.

[3]Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, ss. 273.1(2)

[4] Campbell, R. (2012). Transcript “The Neurobiology of Sexual Assault”. An NIJ Research for the Real World Seminar. https://nij.gov/multimedia/presenter/presenter-campbell/Pages/presenter-campbell-transcript.aspx.

[5] Smith, S. G., & Breiding, M. J. (2011). Chronic disease and health behaviours linked to experiences of non-consensual sex among women and men. Public Health, 125, 653-659.

[6] Loya, R. M. (2014). Rape as an economic crime: the impact of sexual violence on survivors’ employment and economic well-being. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(16), 2793-2813.

[7] Merkin (2008); U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board 1988

[8] Gruber and Bjorn (1982); Loy and Stewart 1984

[9] “Men as Survivors of Sexual Violence.” AfterDeployment, 13 Sep 2017

[10] Morral, Andrew R., Kristie Gore, Terry Schell, Barbara Bicksler, Coreen Farris, Madhumita Ghosh Dastidar, Lisa H. Jaycox, Dean Kilpatrick, Steve Kistler, Amy Street, Terri Tanielian and Kayla M. Williams. Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment in the U.S. Military: Highlights from the 2014 RAND Military Workplace Study. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2015. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs.

[11] Ibid

[12] Issue Brief: Sexual Violence Against Women in Canada, https://www.swc-cfc.gc.ca/svawc-vcsfc/index-en.html

[13]Roberts, K. (2016, October 5). The psychology of victim-blaming. The Atlantic. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/10/the-psychology-of-victim-blaming/502661

[14] Strömwall, L., Alfredsson, H., & Landström, S. (2012). Blame attributions and rape: Effects of belief in a just world and relationship level. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 1-8 doi:10.1111/j.2044-8333.2012.02044.x

[15] Avoiding victim blaming. (2015). Retrieved from http://stoprelationshipabuse.org/educated/avoiding-victim-blaming

[16] Fear of the negative consequences for reporting was cited by 35% of the Stats Can survey respondents as their main reason for not coming forward.

Page details

- Date modified: