D-Day: The RCAF and Second Tactical Air Force

News Article / May 14, 2019

Click on the photo under “Image Gallery” to see more photos.

By Major (retired) William March

June 6, 2019, marks the 75th anniversary of D-Day—the Allied invasion of Normandy.

The successful invasion marked the turning point in the Second World War.

The Royal Air Force’s 2nd Tactical Air Force (2TAF) was created to provide direct air support to the invasion forces.

Originally formed on June 1, 1943, it was modelled after the Desert Air Force and the Anglo-American North African Tactical Air Force. Primarily envisaged as a fighter and fighter-bomber organization, hard lessons-learned during the African campaigns resulted in 2TAF’s having a light and medium bomber component as well.

On D-Day, 2TAF was composed of four separate groups: No. 2 Group (Bomber Command) with 12 squadrons; No. 83 Group with 34 reconnaissance, fighter and fighter-bomber squadrons; No. 84 Group with 31 squadrons; and No. 85 Group with 21 ½ squadrons. This gave 2TAF an approximate total of 1,576 aircraft in 98 ½ squadrons to support the invasion.

Like the other elements of the Allied air force, 2TAF’s mission began long before June 6, 1944. Almost constant reconnaissance flights were conducted over Normandy to be sure, but an equal or greater number were flown throughout Occupied Europe to keep the enemy guessing about the actual site of the attack.

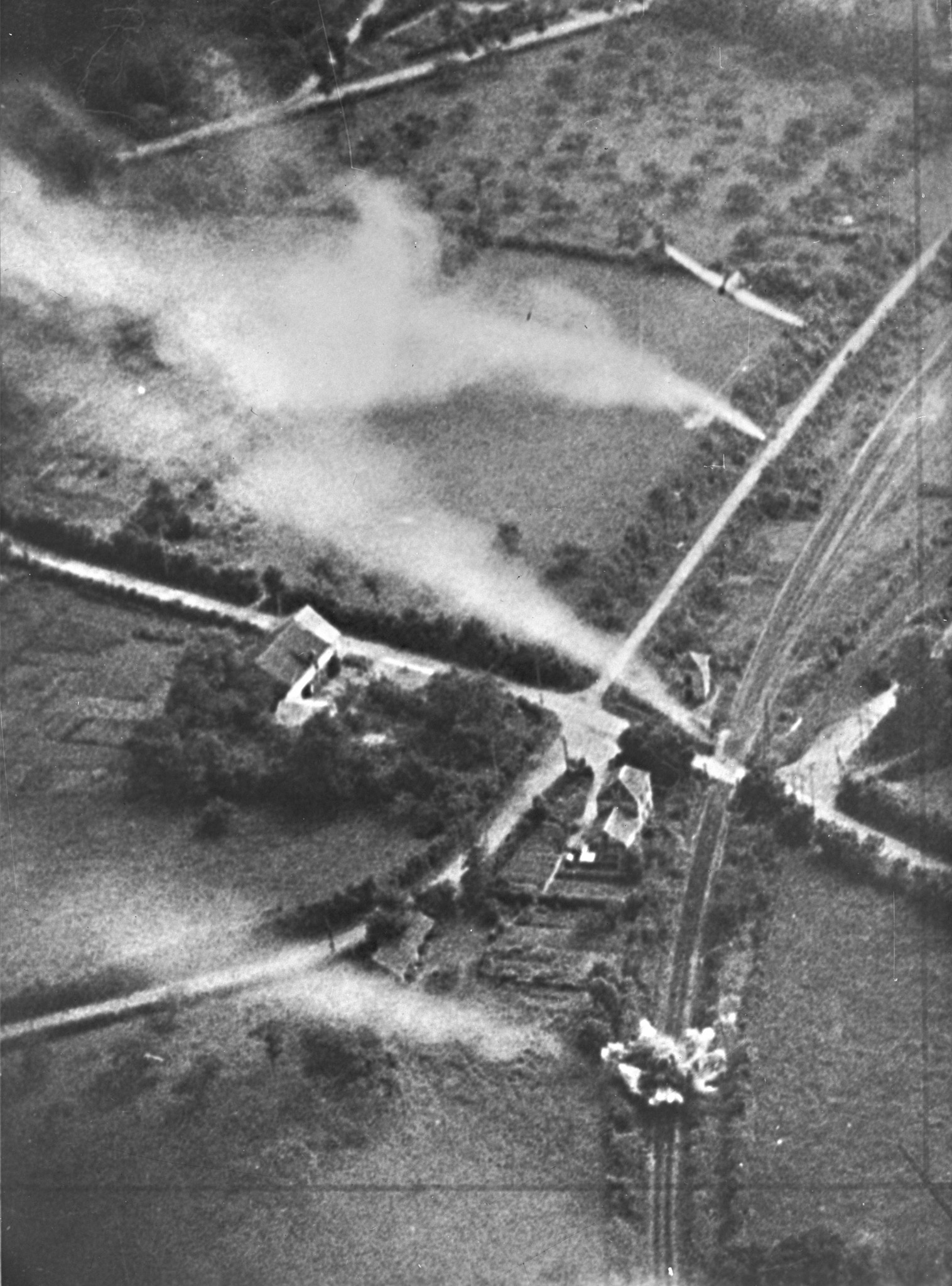

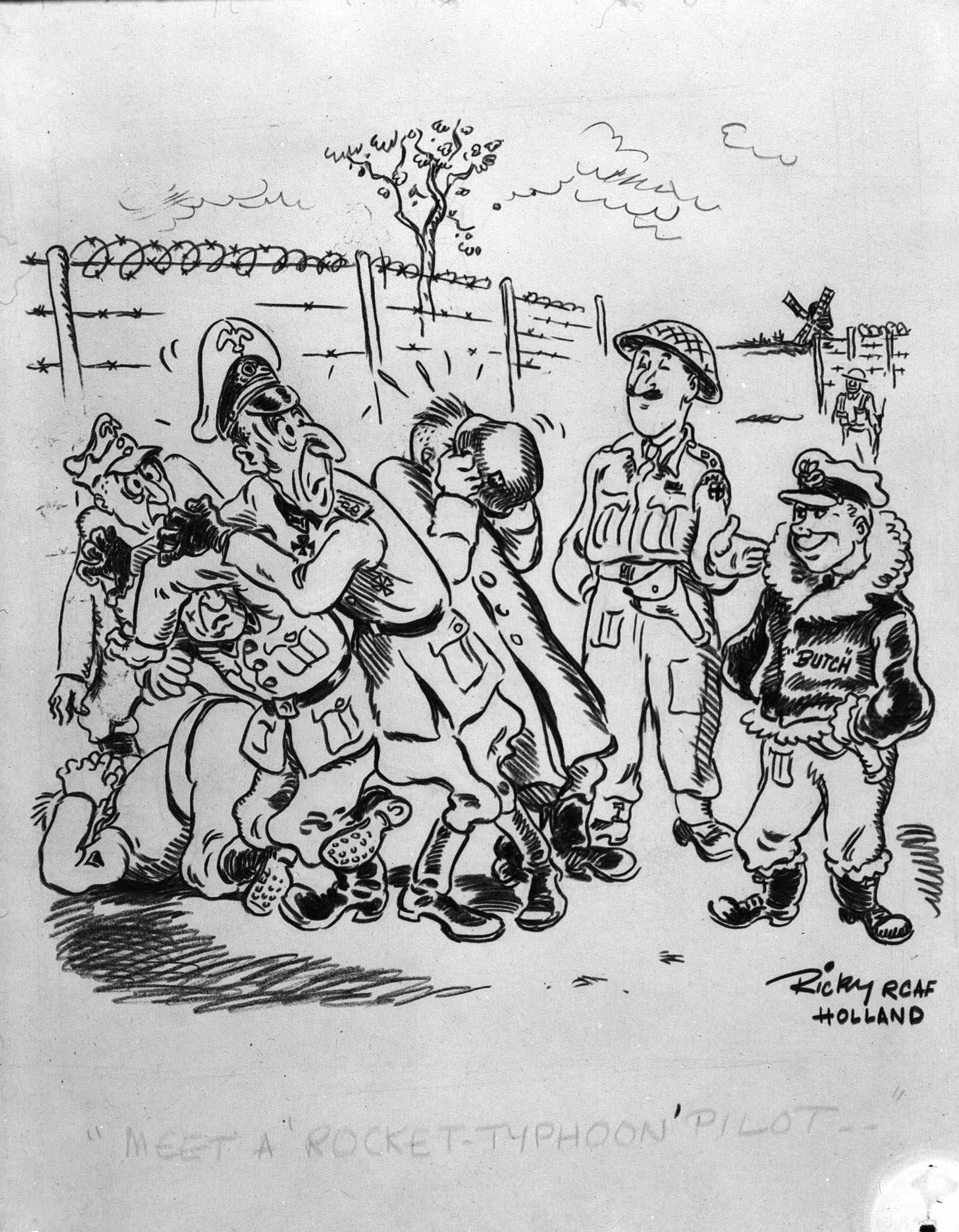

Bombers from No. 2 Group took part in the interdiction campaign conducted by Bomber Command against German transport and communication centres. The fighter-bombers struck at anything that moved, while the fighters engaged in day and night sweeps of German airfields, seeking to destroy as many enemy aircraft as possible. All of these efforts were undertaken with the sole purpose of ensuring that the assault divisions made it ashore.

Of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) squadrons belonging to 2TAF, 16 served with No. 83 Group; they were organized, for the most part, into Canadian wings. The pilots of No. 126 (RCAF) Wing had been briefed about D-Day late on the evening on June 5 and knew what would be required of them over the next several days.

Early in in pre-dawn light, Spitfire IXBs from 400, 411 and 412 Squadrons took off into the overcast sky. The weather for the “big day” would remain overcast, but with visibility of eight kilometres or so, it was suitable for providing air cover. In conjunction with aircraft from RAF wings, which included Spitfires from RCAF’s 402 Squadron (part of 142 Wing), they positioned themselves below 5,000 feet (1,524 metres), over the beaches to guard against German aircraft that might try to hamper the invasion.

Throughout the day, the pilots returned to their fields, refuelled, and returned to their operation area. No enemy aircraft were encountered, and the pilots found themselves watching the unfolding assault below.

For the pilots of 126 Wing, D-Day was anti-climatic due to the total control of the air that the Allies had achieved over the previous months. The Luftwaffe did not mount a serious challenge until June 7 when, much to the delight of the Canadians, they made an attack on the beach area. The Spitfires from 126 Wing pounced on 18 Ju-88 bombers that were in the process of striking the beaches near St. Aubin, France In the ensuing combat, 12 German aircraft were claimed as destroyed, while the remainder fled with varying degrees of damage.

The same mission was allotted to the pilots of 403, 416 and 421 Squadrons belonging to No. 127 (RCAF) Wing. With the excitement born of this momentous occasion, they took their Spitfires into the sky over the Channel in expectation of furious combat . . . and were sadly disappointed. Again, they found themselves spectators watching the invasion unfold.

As with most of the other units involved, they returned to their fields to snatch a quick meal while their aircraft were serviced, shouting hurried answers to questions thrown at them by the groundcrews, before leaving for another patrol. Each of the 127 Wing squadrons flew four patrols on D-Day and the frustrated, tired pilots knew that they could expect more of the same the following day.

Far busier on D-Day were the reconnaissance squadrons of No. 128 (RCAF) Wing.

The Spitfire XIs of 400 Squadron conducted high-level reconnaissance flights, while Mustangs from 414 and 430 Squadrons provided low-level reconnaissance and naval gunfire support. The Mustang pilots helped place naval gunfire where it was most needed—in most cases against German coastal defences and inland targets in the invasion area. They would locate a target, contact their associated ship and proceed to correct the fire until the target was destroyed. The pattern was repeated numerous times throughout the day, with the pilots commenting on the turbulence caused by the passing naval shells as they sped towards the target.

Three Mustangs from 430 Squadron were sent on a low-level pass over some roads just inland from the beaches in search of German transport when they were “bounced” by four German FW-190s during one of the rare Luftwaffe attacks on D-Day. The fight was brief, but deadly for the Canadians. Flying Officer Jack Scott Cox, 23, from Brockville, Ontario, was shot down and killed. With the arrival of two more enemy fighters, the remaining Mustangs beat a hasty retreat.

Spitfires from No. 144 (RCAF) Wing also found themselves providing “top cover” over the beaches. Every available aircraft from 441, 442, and 443 Squadrons flew four sorties throughout the course of D-Day.

Wing Commander “Johnnie” Johnson, RAF, led the wing’s 36 aircraft to their station over beaches. Watching the assault below, Wing Commander Johnson noted that “Here and there the enemy appeared to be putting up a stiff resistance: we saw frequent bursts of mortar and machine-gun fire directed against our troops and equipment on the beaches. Small parties of men could be seen making their way to the beach huts and houses on the sea front, many of which were on fire.”

But the greatest danger to the pilots lay in the “mass of Allied aircraft, which roamed restlessly to and fro over the assault areas. Medium bombers, light bombers, fighter-bombers, fighters, reconnaissance, artillery and naval aircraft swamped the limited air space below the clod, and on two occasions, we had to swerve violently to avoid head-on collisions.”

With the coming of darkness, the day-fighter squadrons belonging to No. 83 Group retired from the beaches and were replaced by night-fighters from No. 85 Group. Two Canadian squadrons, 409 and 410, equipped with Mosquitos, took part in these operations.

Much like their day-time counterparts, they found few targets. Had the Luftwaffe shown up, the night-fighters would have had the additional advantage of mobile Ground Control Interception (GCI) radar that were operating on the beach-head by the evening of June 6.

More than 1,800 airmen, including a number of Canadians, had come ashore with the invasion forces. Subjected to sustained and accurate artillery fire, a number of them were killed and wounded including Canadian Corporal Francis Edward Day from Winona, Ontario, who had joined the RAF as a communication technician. He was killed on Omaha Beach as part of No. 15082 GCI Radar Unit, which landed to support American forces.

Although little in the way of air-to-air combat occurred over the beaches on D-Day, the Allies could not be sure that the Luftwaffe would not offer determined resistance. Indeed, a little more than two years previously, the skies over Dieppe had seen some of the most vicious air combat of the war.

To ensure that the invasion forces would not be molested from the air, more than 5,400 fighters were assigned to protect shipping and the amphibious assault. That they were not needed is a testimony to the thorough job that had been done in the months leading up to D-Day.

Designed to follow closely behind the advancing Allied army, 2TAF landed several advance parties along with the assault troops at Normandy. By June 8, these individuals had established two emergency landing strips. Two days later, at a field near Sainte-Croix-sur-Mer, 441, 442, and 443 Squadrons of No. 144 (RCAF) Wing, became the first Allied air force units to operate from French soil since 1940.

They had accomplished their mission in fine fashion.

Page details

- Date modified: