Chief Human Resources Officer of Canada Transition Binder

On this page

- People Management in the Federal Public Sector

- The Future of Work in the Public Service

- Data Pack

- Forecasted OCHRO Budget 2022-2023 and HR overview

- OCHRO Integrated Business Plan Placemat

- Proposed 2023-2024 OCHRO Integrated Business Plan

- Driving Frameworks

People Management in the Federal Public Sector

In this section

By the Numbers: Overview of the Federal Public Sector

Public service employees impact the lives of Canadians every day through an array of services and programs. The federal government is the largest employer in Canada with total compensation cost of $79.7B (2020-21)

Figure 1 - Text version

| 2022 | |

|---|---|

| CPA | 254,309 |

| SA | 81,648 |

| RCMP | 21,678 |

| CAF | 87,632 |

| Crown Corps | 137,327 |

| Total in graph includes minister's staff (758) | 582,594 |

The Treasury Board serves as the Employer for 254, 309 employees (as of March 2022) for the 69 organizations listed in Schedules I and IV of the Financial Administration Act, constituting the Core Public Administration (CPA).

* Includes $15.3B net actuarial losses and $4.2B in interest expenses associated with personnel costs

** RCMP public service employees are included in Core Public Administration

RCMP regular and civilian members included separately (machinery change of June 2017 not included)

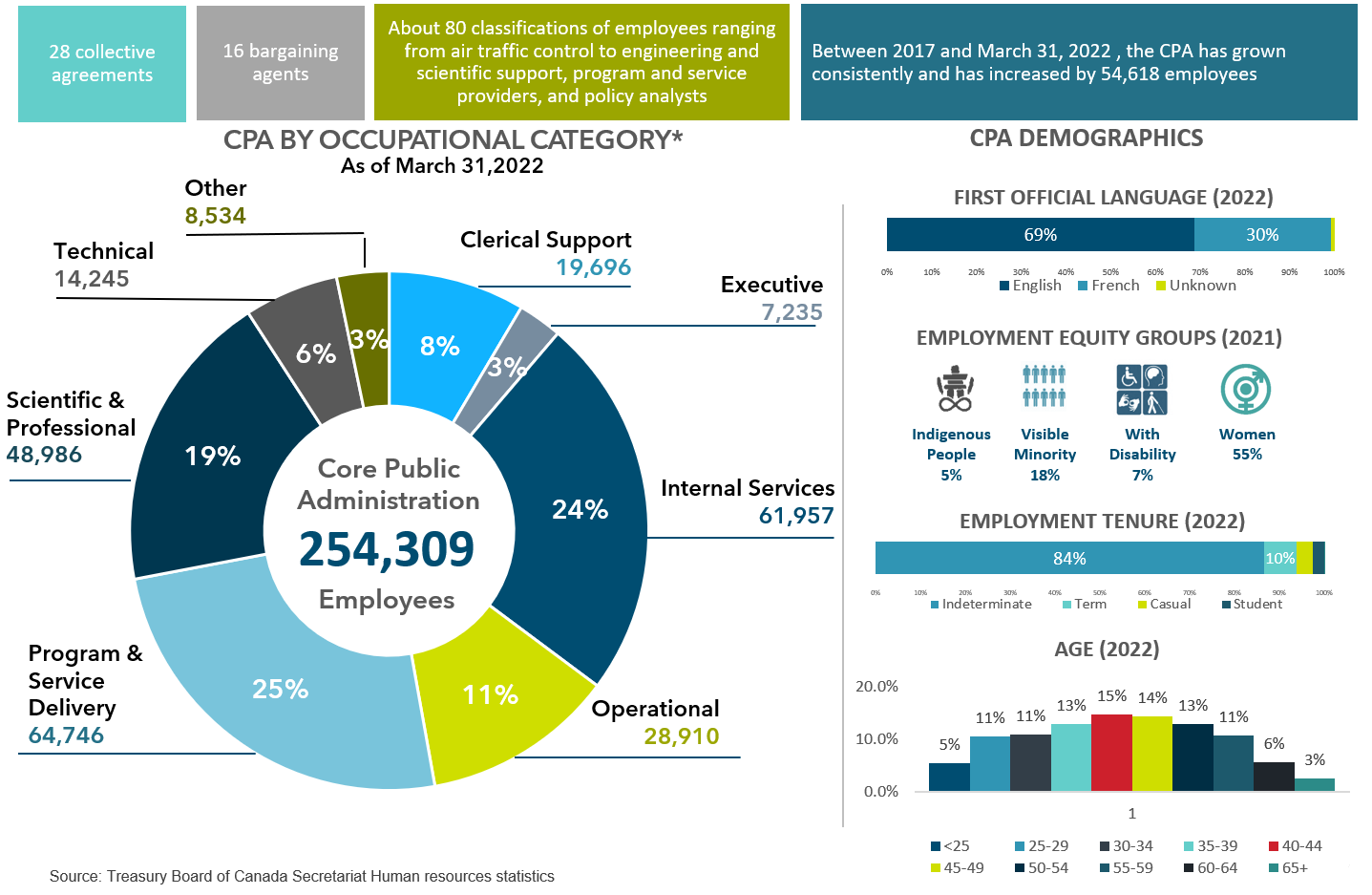

Figure 2 - Text version

Pie Chart: CPA by occupational category*

As of March 31, 2022

Core Public Administration 254,309 Employees

Other 8,534 / 3%

Executives 7,235 / 3%

Technical 14,453 / 6%

Clerical support 19,696 / 8%

Operational 28,910 / 11%

Scientific and Professional 48 ],986 / 19%

Internal Services 61,957 / 24%

Program and Service Delivery 64,746 / 25%

People Management in the CPA

Treasury Board as the employer

Established in 1867, Treasury Board (TB) is the only statutory Cabinet Committee. It has several responsibilities including being the Employer for the CPA; these responsibilities are delegated to the Chief Human Resources Officer through the Financial Administration Act

As the employer, TB has three primary duties:

- Establishing compensation and terms and conditions of employment for represented employees and executives

- Collective Agreements govern key aspects between the relationship between employer and employee (e.g,. rates of pay, leave allowances, classification)

- Pension plans that are set in legislation and not subject to bargaining

- Benefit plans (Health, Dental, and Disability Insurance) are negotiated outside the bargaining process. Plans are for both employees and retirees

- Setting policy direction for people management. The People Management Policy suite consists of two policies and 22 directives

- Policy on People Management provides Deputy Heads with support in developing and sustaining a high-performing workforce

- The Policy on the Management of Executives establishes the authorities and responsibilities of Deputy Heads and the CHRO for EX management

- Maintaining a healthy, diverse, inclusive, bilingual and safe workplace. This is achieved thorough:

- Developing innovative solutions for recruitment and talent management

- Providing guidance on how to develop and implement measures to support the Federal Public Service Mental Health Strategy

- Supporting government implementation of the Official Languages Act in federal institutions

- Providing clear expectations for behaviour and shared Values and Ethics

People Management Roles and Responsibilities

There are distributed accountabilities and roles across the Government of Canada for people management

- OCHRO

- The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (OCHRO) supports TB in its role as the employer by driving excellence in people management and providing guidance to support consistency across the public service

- Deputy Heads

- Hold primary responsibility for human resources management within their organizations. This includes directing the administration of financial and human resources

- PCO

- The Privy Council Office (PCO) Supports the Clerk as Head of the Public Service, including directing public service-wide people management priorities

OCHRO’s Mandate

OCHRO was established as part of Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) in 2009. The context of people management has changed dramatically since then with heightened expectations and increasingly complex issues to address

2009

Narrow and focused mandate:

- People Management

- Total compensation

- Collective bargaining

- Classification

- Official languages

- Employment equity

- Values and ethics

- PS Data

- Mental health

Today

Broader mandate which includes the delivery of 23 Ministerial Mandate Letter commitments:

- Crisis management, managing COVID and post-pandemic planning

- Diversity and inclusion, workplace harassment, discrimination and anti-racism

- Fundamental review of people management policies, organization of work and classification models

- Future of work research and experimentation

- Expanded business owner role for HR systems and pay stabilization

- Complex bargaining environments and modernization and adaptation of total compensation model

- Collective management of heads of HR and renewal and inclusive talent management of EXs

- Support for Beyond 2020 Framework

- Expanded stakeholder management and engagement

Key partners in human resources management

There are four other key partners that work closely with OCHRO and who are responsible for the various aspects of human resources management within government

Public Service Commission

Safeguards the integrity of the staffing system and the non-partisanship of the public service and manages the tools for public service recruitment

Public Services and Procurement Canada

Acts as the central purchasing agent, real property manager, treasurer, accountant, pay and pension administrator, integrity adviser and translation services for the public service

Canada School of Public Service

Provides learning, training, and professional development opportunities to public servants and helps Deputy Heads meet the learning needs of their organizations

Shared Services Canada

Responsible for delivering information technology (IT) and network services to partner organizations to support the delivery of federal programs and services

How OCHRO delivers on its mandate

There are four key business lines within OCHRO that support the role of the Employer

- People Management Strategic Direction

- Developing and supporting policies to ensure an appropriate degree of consistency across the public service, balancing standard requirements with departmental flexibility on a range of HR issues such as official languages, executive leadership, diversity, inclusion and mental health, and telework

- Policy Planning, Research and Renewal

- Data collection and reporting related to people management including the annual Public Service Employee Survey (PSES); integrated strategic policy and planning to guide and improve outcomes on the future of work; and, research, analysis, engagement and experimentation, including innovative approaches, such as behavioral science and human-centered design

- Total Compensation Negotiations and Oversight

- Negotiating terms and conditions of employment with bargaining agents and maintaining effective relationships; leading development of pay equity plans for the CPA and RCMP; providing centralized expertise to departments on labour relations, Ministers’ offices, managing compensation and classification; and, managing the public service pension and group insurance benefit plans

- HR Systems and Processes

- Oversight for enterprise-wide HR systems, processes, standards and controls; engagement with key administrative partners including Shared Services Canada and Public Services and Procurement Canada; and, working on a set of modern tools that support a wide range of HR functions across the public service

How Government manages its workforce is changing

Putting people first is the foundation to our future success– the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the need to adapt and turn challenges into opportunities

The Future of Work Framework

People management

Inclusive

Talent, Skills, & Inclusion

The Public Service is skilled, diverse, inclusive, accessible, and human-centric

Agile

Flexible Work Models

A distributed, flexible, productive workforce and welcoming workplace

Equipped

Organization of Work

The Public Service classifies and compensates work to facilitate agility and drive employer competitiveness in response to the changing nature of work

Digital & Data Driven

The Public Service is digitally enabled, and leverages HR systems and data to support strategic decision-making

Culture, Change Management, Mindsets & Behaviours

A Public Service that embodies the future of work vision

Annexes

Annex A: Occupational Category Breakdown

Clerical Support

- CM - Communications

- CR - Clerical and Regulatory

- DA - Data Processing

- OE - Office Equipment

- ST - Secretarial, Stenographic and Typing

Executive

- EX - Executive

- LC - Law Management

Internal Services

- AS - Administrative Services

- FI - Financial Management

- IS - Information Services

- OM - Organization and Methods

- PE - Personnel Administration

- PG - Purchasing and Supply

- TR - Translation

Operational

- CX - Correctional Services

- FB - Border Services

- FR - Firefighters

- GL - General Labour and Trades

- GS - General Services

- HP - Heating, Power and Stationary

- Plant Operations

- HS - Hospital Services

- LI - Lightkeepers

- PO - Police Operations Support Group

- PR - Non-Supervisory Printing Services and Printing Operations (Supervisory) Group

- SC - Ships Crews

- SR - Ship Repair and Ship Repair Chargehands and Production Supervisors

Other

- AM - Audit Committee Members

- CA - Career Assignment Program

- DM - Deputy Ministers

- Federal Judges (Non-classified)

- MM - Management Trainee “Ab Initio”

- (non-employees)

- Non-classified

- OC - Governor-in-Council Appointees

- PL - Leadership Programs (LP) Group

- Student

Program & Service Delivery

- CO - Commerce

- FS - Foreign Service

- IT - Information Technology

- PM - Programme Administration

- PMMCO - Mediation and Conciliation

- WP - Welfare Programmes

Scientific and Professional

- AC - Actuarial Science

- AG - Agriculture

- AR - Architecture and Town Planning

- AU - Auditing

- BI - Biological Sciences

- CH - Chemistry

- DE - Dentistry

- DS - Defence Scientific Service

- EC - Economics and Social Science Services

- ED - Education

- EN - Engineering and Land Survey

- FO - Forestry

- HR - Historical Research

- LA - Law

- LP - Law Practitioner

- LS - Library Science

- MA - Mathematics

- MD - Medicine

- MT - Meteorology

- ND - Nutrition and Dietetics

- NU - Nursing

- OP - Occupational and Physical Therapy

- PC - Physical Sciences

- PH - Pharmacy

- PS - Psychology

- SE - Scientific Research

- SG - Scientific Regulation and Patent

- SW - Social Work

- UT - University Teaching

- VM - Veterinary Medicine

Technical

- AI - Air Traffic Control

- AO - Aircraft Operations

- DD - Drafting and Illustration

- EG - Engineering and Scientific Support

- EL - Electronics

- EU - Educational Support

- GT - General Technical

- PI - Primary Products

- PY - Photography

- RO - Radio Operations

- SO - Ships Officers

- TI - Technical Inspection

Annex B: OCHRO’s Ministerial Mandate Letter Commitments

- Ensure that Public Service workplaces are free from sexual harassment and violence, as well as racism and all forms of hate

- Support departments in implementing the plans outlined in their responses to the Call to Action on Anti-Racism, Equity and Inclusion

- Ensure the use of disaggregated data to track the Public Service's progress in implementing the plans outlined in their responses to the Call to Action on Anti-Racism, Equity and Inclusion

- Build a whole-of-government approach for the improved collection, analysis, availability and publication of disaggregated data

- Create a Diversity Fellowship to mentor and sponsor diverse groups of public servants

- Implement an action plan to increase representation in hiring, appointments and leadership development

- Create a fellowship for 1,000 students and new graduates

- Offer language training to post-secondary students to reduce barriers to public service recruitment

- Offer language programs to racialized public service employees

- Expand public service recruitment programs to international students and permanent residents

- Help community organizations support students to enter the Public Service

- Establish a mental health fund for Black public servants

- Support career advancement, training, sponsorship and educational opportunities for Black public servants

- Advance the implementation of the Pay Equity Act across the Public Service

- Bring forward a coherent and coordinated plan for the future of work within the Public Service

- Develop a long-term, government-wide Public Service Skills Strategy

- Improve government whistleblower protections and supports, including exploring possible amendments to the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act

- Ensure that Canadians across the country can receive services from federal institutions in both official languages

- Implement measures outlined in the White Paper, English and French: Towards a Substantive Equality of Official Languages in Canada that are related to the Public Service

- Hire 5,000 new public servants with disabilities by 2025

- Require Crown corporations to implement gender and diversity reporting, starting in 2022

- Ensure vaccination across the Public Service

- Bargain in good faith with Canada's public sector unions

Annex C: Federal Governance Structure

Despite differences in governance structure, all departments, agencies and Crown corporations have a relationship with a responsible minister

All are ultimately answerable to Parliament and the public

Annex D: Federal Public Sector HR Legislative Framework

- Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- Guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it; subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can demonstrably be justified in a free and democratic society. Courts have determined that the “freedom of association" clause confers rights of collective bargaining.

- Financial Administration Act (FAA)

- Confers HR management powers to the TB and/or Deputy Heads (Organization of Work, Classification, Discipline, Termination of Employment, Terms and Conditions of Employment, Establishment and modification of the PS benefit plan).

- Public Service Employment Act (PSEA)

- Sets out staffing rules, restrictions on political activities administered by the Public Service Commission.

- Federal Public Sector Labour Relations Act (FPSLRA)

- Governs collective bargaining and labour relations in the federal public service.

- Canadian Human Rights Act (CHRA)

- Prohibits federally regulated employers from discriminating based on the grounds listed in the Act. It also protects the right to pay equity by establishing that it is a discriminatory practice for an employer to establish differences in wages between male and female employees who perform work of equal value.

- Employment Equity Act (EEA)

- Establishes rules for employers to engage in proactive employment practices to increase the representation of four designated groups: women, people with disabilities, aboriginal peoples, and visible minorities.

- Accessible Canada Act (ACA)

- Provides for the development of accessibility standards and gives the Government the authority to work with stakeholders and persons with disabilities to create new accessibility regulations that will apply to sectors within the federal jurisdiction.

- Pay Equity Act (PEA)

- Requires Treasury Board and other federal employers to proactively review compensation and ensure that they are providing equal pay for work of equal value.

- Canada Labour Code, Part II

- Sets out the Occupational Health & Safety regime.

- Official Languages Act

- Assigns responsibilities to Treasury Board and its President, regulations and policies on communications and services to the public, language of work in federal institutions and the participation of English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians in federal institutions.

- Public Service Superannuation Act & other pension legislation

- Sets out the terms and conditions for pension benefits to current and former federal public sector employees, and their survivors and dependents.

- The Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act

- Establishes a secure and confidential process for disclosing serious wrongdoing in the workplace, as well as protection from acts of reprisal.

- The Canada School of Public Service Act

- Assigns responsibility to the Canada School of Public Service to assist deputy heads in meeting their departmental learning needs.

- The Department of Public Works and Government Services Act

- Assigns responsibility to PSPC for the administration and delivery of pay and benefits.

The Future of Work in the Public Service

Discussion Paper – June 2022

In this section

Introduction

The Public Service workplace and workforce are changing rapidly; from increased focus on both diversity and wellness to the introduction of new technology to the recent experience of widespread remote work, now – more than ever – excellence in people management needs to be at the core of any vision of the future of work in the Public Service.

This paper outlines OCHRO’s vision for what the Public Service could be and an analytical frame to help get there, inspired by a statement from the Clerk, Janice Charette, at APEX 2021:

“…so much has changed, that we cannot return to the way it was before COVID-19…we must remain agile, flexible, and receptive as we have been during the crisis…”

It is an early articulation of how the Public Service can use this moment of change to shape a future of work that focuses on excellence in people management and a people-first culture. It is meant to highlight to decision-makers what is possible and provoke discussion about how to get there.Footnote 1 The next steps will be to build consensus around this vision and develop more detailed diagnostiques to identify the work that will need to be done to achieve our shared vision for the future of the Public Service, including updating policy and legislative frameworks, and tailoring departmental plans.

Tectonic Trends

To anticipate the future of work and prepare for change, it is important to keep in mind broader trends that could affect the Public Service, such as climate change and resource scarcity; demographic and social changes; technological breakthroughs; and urbanization, to name a few. Technological change continues to accelerate. Rudimentary automation and artificial intelligence will be augmented by ever more complex learning programs that will enable machines to do a broad range of repetitive, mundane, and higher-risk tasks. Data analytics will drive decision-making, based on increasing databases of biometric and behavioural data. Industrial applications will be based on an increasing array of sophisticated sensors and nano technology. Human interactions will be transformed by virtual and augmented reality.

Social change is also happening at a rapid pace. Broader societal objectives such as environmental stewardship and management of scarce resources are gaining ever more support. Increased life expectancy will necessitate changes in healthcare and wellness management, whereby data, technology, automation, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality will combine to change how and where basic health care services are delivered. Growing urbanization will continue to change infrastructure and service requirements across the country. Finally, as the Canadian population becomes increasingly diverse, the Public Service will need to mirror this diversity.

“…a transition to full telework capacity—a situation in which all workers who can plausibly work from home would work all of their hours from home—could, through reduced commuting, lead to a reduction in annual emissions of greenhouse gases of about 8.6 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent in Canada. This represents 6% of the direct greenhouse gas emissions from Canadian households in 2015, and 11% of their emissions attributable to transportation that year.”

A View into the Future of Work

“Not since the industrial revolution have companies really had to think about work design, about what tasks get done and where do those tasks get done, and when and how do you deconstruct work so that it’s done in an optimal manner.”

Source: Global Talent Trends 2022, LinkedIn

These trends, and the upheaval of traditional ways of working caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, present us with a unique opportunity. This is not a debate about whether some or all employees should return to pre-pandemic working habits; it is something much larger. We will need to make choices about how and where work will get done, which types of tasks should be automated, where to invest in needed skills, and how to develop a workforce that is inclusive, innovative, forward-looking, and flexible. The Public Service is not alone in this moment of change; across the globe, we are seeing a fundamental shift from the future of work being a concept to a it being an operational reality.

The impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on traditional ways of working offer many insights that can help us think about the future of work. Three lessons are particularly significant for the Public Service. First, work is not a place but an activity. The gravitational pull of the office has been broken and will likely continue to erode as technology and work culture evolve. Second, management by presence or by timecard is vastly over-used and inhibits employee flexibility. Third, the impacts of new ways of working are not uniform across a diverse workforce. For example, a 2021 survey conducted by Gartner found that 51% of women who weren’t working remotely before, but have been since the pandemic, feel their level of safety has increased and that knowledge workers with a disability are more likely to feel respected in a hybrid environment (81%) than when on-site (56%). Further, the Survey of Working Arrangements and AttitudesFootnote 2 suggests being able to work shorter and more flexible hours from home could help increase labour supply by appealing to many people who would otherwise not be in the labor force such as older workers, those caring for young children or older relatives, persons with disabilities, and those living in rural areas.

“…hybrid working from home increases average productivity by about five percent. In fact, the productivity gains seem to be rising as companies and employees learn how to take advantage of remote work opportunities. In-person work helps with creativity and innovation through formal and informal meetings. It can also be good for fostering an esprit de corps.”

It is also worth noting that organizations that had already invested in the tools to support telework were best able to continue operations with minimal interruption when the pandemic response necessitated off-site work. Finding ways to maximize the flexibility of how, where, and by whom work gets done leads to nimbler operations and an improved ability to respond to unforeseen circumstances.

The recent widespread remote work experiences are a launching point towards new ways of working that, if we are intentional about embracing, offer multiple benefits to the Government of Canada such as improved services, a nationally distributed workforce that mirrors Canada’s diversity, more efficient use of government-owned assets, and a reduced environmental footprint of operations.

A Public Service Journey to the Future of Work

The future of work in the Public Service can be mapped to the three dimensions of Public Service renewal: inclusive (workforce and the employee experience), equipped (the workplace and how work is enabled), and agile (the work and how outcomes are achieved). Four key questions, set out below, will aid in exploring each of these dimensions:

- How do we attract, retain and foster talent that is inclusive, skilled, diverse, and people-first?

- How do we organize flexible work models to move towards a distributed workforce?

- How do we organize and compensate work in a way that is equitable and that drives outcomes and employer competitiveness?

- How do we leverage HR systems and data to support strategic people-related decision-making?

These questions lead us to identify four imperatives that intersect and can lead us to view and re-invent “People Management”.

With planning organized around these imperatives and supported by research, data, change management, and the right culture, the future of work will emerge.

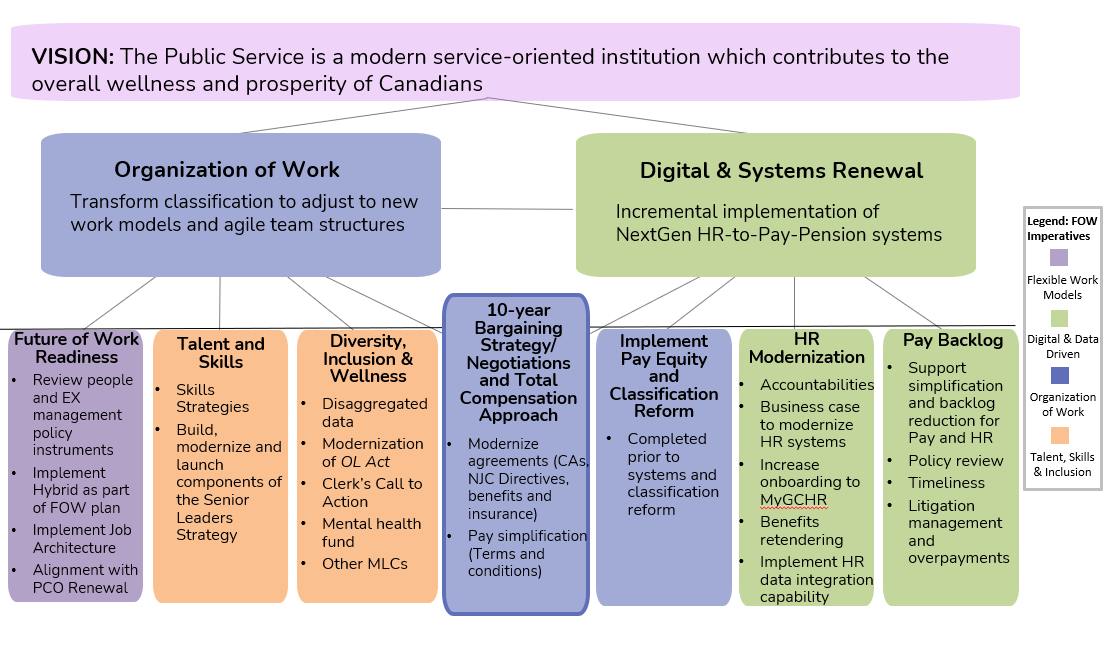

Four imperatives for a future-enabled Public Service

The Future of Work Framework

People management

Inclusive

Talent, Skills, & Inclusion

The Public Service is skilled, diverse, inclusive, accessible, and human-centric

Agile

Flexible Work Models

A distributed, flexible, productive workforce and welcoming workplace

Equipped

Organization of Work

The Public Service classifies and compensates work to facilitate agility and drive employer competitiveness in response to the changing nature of work

Digital & Data Driven

The Public Service is digitally enabled, and leverages HR systems and data to support strategic decision-making

Culture, Change Management, Mindsets & Behaviours

A Public Service that embodies the future of work vision

Imperative 1 – Talent, Skills, and Inclusion

The Public Service is skilled, diverse, inclusive, accessible, and human-centric

Context

Skilled: The market for talent is increasingly competitive. The Public Service will need to adopt a multi-pronged strategy to invest in the growth of existing employees (“build”), get the right talent to the right place at the right time (“borrow”), and hire talent to fill short-term needs and skills gaps (“buy”). This will require increasing the tools available to managers to win the war for talent as well as ensure that public servants have opportunities to advance their skill sets.

The skills requirements for the Public Service are rapidly changing, with ever greater emphasis on data analytics, technology, media, communication, and skills such as meta-cognitive skills and emotional intelligence. Basic data literacy, once a specialized skill, will be as common as typing is today. Data will be used in essentially every function, including core people enablement functions such as managing and continuously improving performance. Other skills that the Public Service will need to further cultivate include strategic foresight, prototyping, human-centred design, experimentation, systems thinking, storytelling and visualization, among others.

Recruitment will shift to focus on a candidate’s curiosity, empathy, initiative, and ability to learn certain skillsets, rather than on specific knowledge or perishable skills. Skills can be taught much more easily than initiative, curiosity, or empathy.

To address these skills gaps, Public Service competency frameworks need to continuously evolve and inform learning strategies, recruitment, and performance criteria.

The Public Service also requires a culture of continuous learning which includes space for formal training, experimentation, mentoring, and learning-by-doing. All of these learning strategies, and others, should be incorporated into a “learning career”, where employees are expected to use a portion of their paid working hours to enhance and maintain skills. Reskilling and continuous learning are becoming increasingly relevant in other sectors as well. According to a 2020 World Economic Forum report, 94% of business leaders expect employees to pick up new skills on the job, compared to 65% in 2018, making the market for talent even more competitive.

Diverse and Inclusive: Diversity is a strength for the Public Service, just as it is for private sector enterprises, bringing diverse perspectives and richness of experience for better policy and decision-making. To be an employer of choice for all Canadians, it is imperative that the Public Service continue to advance as awareness and understanding of concepts such as unconscious bias and colonialism continue to evolve. Diversity and inclusion considerations need to be meaningfully embedded in decision-making, including through systematic integration of GBA+ principles. Further, true inclusion is needed for people to feel like they can bring their whole selves to work and contribute everything they have to offer, and to maximize the potential of what the Public Service has to offer in service to Canadians.AT&T now invests around $250 million annually in T University, which enables existing employees to develop in-demand expertise in areas such as data science and cybersecurity. It also provides anywhere from $15 million to $34 million annually in tuition aidto support employees with learning outside of the company.

“Our research has repeatedly shown that gender and ethnic diversity, inclusion, and performance go hand in hand.”

People-First: To remain relevant and responsive to the needs of Canadians, the Public Service’s approach to talent will be key to its success in the years to come. As the largest employer in Canada, the Public Service can also influence standards for employer excellence.

Employee experience is a wholistic lens that considers multiple factors and is increasingly viewed as a key indicator of organizational performance. In addition to more traditional indicators of harassment and discrimination, it includes providing an accessible environment where employees identify with the purpose of their work, are able to pursue areas of interest, and are trusted and valued for their contributions. It also has a focus on individual wellness, including physical and mental health, beyond traditional mechanisms such as leave and health benefits. Further, people-first workplaces set aside traditional assumptions about place of work, hours of work, and hierarchy.

What does a skilled, diverse, inclusive, and people-first Public Service look like in the future?

- The Public Service has a competency framework providing a common way of defining and measuring skills. It understands the skills it has and the skills it needs and works to close the gaps in order to provide services that meet Canadians’ evolving needs.

- The way we identify, recruit, develop, mobilize, incentivize, and reward leadership is centered around a life-cycle approach to talent. Expectations for senior leaders to drive an inclusive culture are embedded in key leadership competencies and leader character attributes. A mindset of leadership at all levels is instilled and valued.

- Managers can access people with the skill sets that they need in a timely manner. There are minimal barriers to moving in, out and/or across the Public Service to address government priorities and help employees gain new skills and experience.

- The Public Service manages talent and cultivates a learning culture for all public servants, including managers. Learning opportunities, both formal and informal, are made available and are a part of the employee’s regular activities.

- Performance management is continuous, multi-directional, and focuses on learning and improvement. Managers are not just supervisors but coaches providing and supporting challenging work. Performance and talent management are integrated to increase employee engagement, learning, leadership development, succession planning, and productivity, and the linkages between them, are strengthened.

- We have a language training framework that takes into account the specific needs of Employment Equity groups and includes options for distance language training.

- Technology, automation, and artificial intelligence are a source of complementary “talent” to human skills.

Leading up to 2025, on average, companies estimate that around 40% of workers will require reskilling of six months or less.

- The Public Service pro-actively re-skills employees whose positions may be affected by new technologies or approaches.

- The Public Service is accessible and represents the diversity of Canada’s people from the perspective of the Public Service as a whole, as well as organizations, functions, and levels.

- All employees have the skills to embed considerations such as GBA+, official languages, employment equity, and accessibility in their work.

- Disaggregated workforce data is collected and used to monitor impacts of change on various groups.

- The Public Service is inclusive, and employees feel their ideas are respected and valued.

- The Public Service is a model of reconciliation and works with Indigenous employees towards improving the work environment, to de-colonize the workplace, its culture, and its processes.

"Fully including Indigenous Peoplesin Canada’s Public Service will enhance Canada’s ability to identify itself as a fully inclusiveworkplace."

- The Public Service works with Black, Indigenous, and other racialized employees to develop solutions to address the barriers and disadvantages they face in Public Service workplaces and systems.

- Employees, including managers, see their work as meaningful. Public servants are curious and driven to contribute ideas, innovate, and improve outcomes. They cultivate relationships that foster psychological safety and opportunities to provide meaningful input into decision-making.

- Managers and employees alike see their jobs as being compatible with their health and psychological well-being. Disaggregated data on health and psychological well-being is regularly sought out and leveraged to adjust employee supports accordingly. Team members are engaged with each other and take steps to ensure the workplace is supporting wellness and not contributing to illness.

- People-first is the basis for designing people enablement strategies and systems and delivering HR services and services to Canadians.

- HR develops data-driven people strategies to enable future-focused business strategies.

Imperative 2 – Flexible Work Models

A distributed, flexible, productive workforce and a welcoming workplace

Context

Figure 3 - Text version

Firms that don't offer weekly work-from-home days risk losing more than 40% of their employees according to surveys of more than 10,000 Americans conducted in June and July 2021. Bar graph: If my employer announced that all employees must fully return to the worksite on August 1, 2021, I would: 57.2% comply and return, 36.4% return but look for a WFH job, 6.4% quit, even without another job.

“…people of color and highly educated women with young childrenplace especially high value on the ability to work from home part of the week. A ban on working from home risks a rush to the exitby these employees.”

The question to be addressed is not how to return to “normal” but how to create a new normal that includes a range of flexibilities around how, where, and when work is done that benefit both employees and managers. Even as some work will need to remain attached to a worksite, maximizing flexibility in work models (e.g. through compressed schedules) is an opportunity to improve broader outcomes, including:

Improved employee experience, talent attraction and retention, and productivity. Increased flexibility for how and where work is done is an important tool for improving employee experience, with positive impacts for accessibility, talent recruitment, retention, and overall productivity.

A more geographically dispersed and diverse workforce. Untying work from worksites provides the opportunity to increase regional diversity in the Public Service workforce and more evenly distribute the economic benefits of Public Service employment across the country (see figure 2). This would contribute to more representative and inclusive policies, programs, and services, and facilitate the recruitment of top talent to the Public Service.

Figure 4 - Text version

| Province | # of Federal Public Service Employees | % of Federal Public Service employees | Canadian Population | % of Canadian Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yukon | 427 | 0.1% | 40,232 | 0.1% |

| Northwest Territories | 571 | 0.2% | 41,070 | 0.1% |

| Nunavut | 334 | 0.1% | 36,858 | 0.1% |

| British Columbia | 26,464 | 8.5% | 5,000,879 | 13.5% |

| Alberta | 17,511 | 5.6% | 4,262,635 | 11.5% |

| Saskatchewan | 6,242 | 2.0% | 1,132,505 | 3.0% |

| Manitoba | 12,156 | 3.9% | 1,342,153 | 3.6% |

| Ontario (excluding NCR) | 43,503 | 14.0% | 13,088,928 | 35.4% |

| National Capital Region | 134,817 | 43.4% | 1,488,307 | 4.0% |

| Québec (excluding NCR) | 33,981 | 10.9% | 8,148,540 | 22.0% |

| New Brunswick | 10,881 | 3.5% | 775,610 | 2.1% |

| Nova Scotia | 11,806 | 3.8% | 969,383 | 2.6% |

| Prince Edward Island | 3,888 | 1.3% | 154,331 | 0.4% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 6,853 | 1.3% | 510,550 | 1.4% |

| Outside Canada | 1,323 | 0.4% |

Reduced real estate costs and greening operations. Adopting flexible and distributed work models is a necessary step in reducing the government’s real estate portfolio as it will allow workspace to be right sized to work that needs a work site and for supporting employee experience. Further, as recommended in the TBS Horizontal Fixed Asset Review, as the federal real property portfolio evolves it can become a strategic enabler by advancing corporate priorities including furthering Indigenous reconciliation, driving digital transformation, and supporting climate resilience and sustainable development.

“With 32,000 buildings, 23 million square meters (m2) of floor space, approximately 20,000 engineering assets, and 39 million hectares of land, the Government of Canada owns and manages the largest fixed asset portfolio in Canada. The government spends approximately $10 billion annually to administer this portfolio.”

As the benefits of a flexible and distributed workforce are realized it will be important to manage the risk of inequities in opportunities and treatment between on-site and off-site employees. This risk could have larger employment equity implications if some demographic groups are more likely to telework than others.

What does a flexible and distributed Public Service look like in the future?

GC Talent Cloud found that job posters that advertised telework received 63% more applications

- Work is tied to a worksite only when necessary. If the work can be performed off-site, the employee can work off-site and participate in their team and organization through virtual collaborative technologies if they prefer.

- For positions where all work can be performed off-site, employees can be located throughout Canada.

- Where operationally unfeasible to work off-site, employees are afforded different flexibilities in how and when work is done.

- The workplace footprint is optimized. Workspace is unassigned by default; some space is maintained and designed for specific employees where necessary. Some space is maintained for group activity such as employee training, collaboration activities, and/or other purposes altogether.

- There is seamless secure, strong, and consistent connectivity, and technology allows the distributed workforce to fully participate and collaborate, regardless of work location. Technology that becomes available in the future, over time, expands the proportion of positions that can be performed off-site.

- Regardless of work location, employees start with the same basic responsibilities and are treated equally.

- Managers have the support, resources, and training to be proficient at leading distributed teams. They maintain a healthy culture that supports equitable treatment of employees irrespective of where the work is performed, they are aware of their potential biases (in favour of on-site employees), and inclusion of off-site employees in decision-making is continuously pursued which helps to avoid unintended consequences.

- Performance assessment for both onsite and offsite employees is focused on outcomes and intricately tied to talent management. Employees are evaluated based on quality of work and outcomes achieved while still meeting learning objectives and maintaining a healthy work cadence and environment.

- The workforce promotes and maintains healthy practices. Technology is used to enhance flexibility rather than to support 24/7 availability for work.

Imperative 3 – Organization of Work

The Public Service classifies and compensates work to facilitate agility and drive employer competitiveness in response to the changing nature of work

Context

“By 2025, 85 million jobs may be displaced by a shift in the division of labour between humans and machines, while 97 million new roles may emerge that are more adapted to the new division of labour between humans, machines and algorithms.”

Technology, including AI and automation, is changing the nature of work. Automation is expected to replace many tasks currently undertaken by people. This is likely to require a mix of strategies including re-skilling and targeted recruitment. It will also require re-organizing work, by consolidating non-automated tasks, which may also have implications for organizational structures. Both automation and artificial intelligence will shift work to more complex tasks with increased reliance on cognitive human skills. In the Core Public Administration alone, approximately 42% of employees work in Administrative Services, Program Administration, or Clerical and Regulatory groups, which have traditionally been the most susceptible to changes in technology and task automation.

“Companies that rapidly allocate talentto opportunities have more than twice the likelihood of strong performance, and they also deliver better resultsper dollar spent.”

The Public Service also needs to be able to acquire the skills and capacity it needs when it needs them. The work of public servants should evolve along with the role of the Public Service. Foresight is required to identify roles that the Public Service will be called on to play in the face of continued global climate and health crises. The COVID-19 crisis proved that we can rapidly deploy resources to priorities in times of need. Drawing on this success, the Public Service could benefit from the increased use of more agile approaches to organizing work, such as teams and individuals who do not have regular files but are deployed to priorities on-demand based on their skill sets. Some examples of this model include departmental surge teams, centres of expertise, and the Free Agents program.

Agility within the workforce, in terms of the ability to move people to where they could have greater impact, could be improved through the focus on continuous learning referenced above, particularly as it relates to lateral development, broadening of skills, and re-skilling.

Agility can also be addressed through diverse employment models, as traditional Public Service employment may not be attractive to all profiles in the labour market. To remain competitive and drive outcomes, the Public Service would benefit from the ability to access niche high-demand skillsets quickly to complement its existing workforce. Temporary resources also allow the Public Service to be more flexible, responding to changing organizational mandates.

“Today’s governments are being asked to solve the problems of the 21st century with a workforce and managerial structure designed for a different era. They continue to address major challenges by creating new, permanent departments and agencies — an unsustainable model in a world of rapidly changing demands fueled by equally rapidly evolving technology.”

Currently, approximately 82% of the Public Service are indeterminate employees and there are 28 collective agreements and 74 occupational groups in the Core Public Administration. In the future, new employment models may emerge. There may be different categories of workers than exist now as work becomes more task-focused and disconnected from how we currently think of jobs and roles. The next generation of workers may not necessarily spend their entire careers in the Public Service and may opt instead to move in and out to broaden their experience. As work is re-organized, this is also likely to have implications for organizations. The future may include flatter structures, and work and workers that exist outside of individual organizations.

Consideration also needs to be given to how work is rewarded, given potential changes to categories of work and workers. For example, the Public Service could offer options within rewards packages that are tailored to employees’ individual circumstances, to increase its competitiveness as an employer. “One-size-fits-all” may not be the way of the future when it comes to organizing and rewarding work.

“Motivations for work are changing. Gains in living standards over the past 150 years are allowing us to spend less of our time working, but are raising expectations about what a job should provide.”

Finally, a people enablement strategy that is people-first should envisage work from an employee perspective: the Public Service needs to provide fulfilling work that is mission-driven and citizen-focused and make it accessible to a diverse workforce. Understanding the employee experience requires engaging employees and understanding their needs, behaviours, and experiences, which can provide rich data to help inform future strategies and initiatives to improve the public service.

How does the Public Service organize work to drive outcomes and compensate work in a way that is equitable and drives employer competitiveness in the future?

- Technology, including automation and artificial intelligence, is integrated quickly and ethically, and leveraged to improve outcomes and provide more fulfilling work.

- The Public Service is agile, quickly and easily moving human resources to where they are needed most within and between organizations.

- Organizations maintain a mix of content and functional expertise and optimally assign employees with the right type of expertise to the right priorities and challenges. Organizations regularly assess the latter through focused reviews.

- The Public Service has surge capacity that can be deployed as needed.

- When agility cannot be sufficiently achieved through surge capacity, organizations can access skills from the labour market quickly and effectively.

- The way in which work is rewarded contributes to the Public Service’s ability to compete for skilled and diverse talent by being equitable, competitive, and flexible.

- Organizations needing resources with in-demand skills have the flexibility to offer competitive compensation.

- Employees have the flexibility to choose a rewards package that is tailored to their personal goals, life stages, and individual circumstances.

- As much as possible, work arrangements are adaptable to individual needs, including time and place of work and terms and conditions of employment.

- Employees are provided with work that both contributes to organizational priorities and offers experiences that are meaningful and responsive to their development needs. The most skilled talent is assigned to the most challenging problems, which improves engagement of top talent and optimizes outcomes. Data-driven insights inform decision-making vis-à-vis aligning work with improvement of organizational outcomes.

Imperative 4 – Digital and Data Driven

The Public Service is digitally enabled, and leverages HR systems and data to support strategic decision-making

Context

“Today, workforce data from multiple sources present opportunities to manage public employees through evidence-based HR policies. Governments are thus increasingly able to recruit, deploy, train, motivate and retain their employees in a scientific and analytic way based on objective HR data.”

Data and automation will be among the most important commodities for enabling people in the future. User-centred HR systems have the potential to provide data that supports self-management, workforce management and enterprise decision-making, reducing bias and risk, increasing transparency and objectivity, and improving decisions and outcomes.

HR systems also have the potential to automate what has traditionally been manual, human-driven, HR processes and transactions, allowing managers and HR professionals alike to focus on complex tasks like interpretation, decision-making and strategizing. They can also help promote agility, and improve consistency and productivity through increased data sharing and decreased processing time and errors, in keeping with security and privacy, and help make informed decisions based on insightful data.

What does a Public Service that leverages HR systems and data to improve people enablement look like in the future?

- Users are at the centre of HR processes and systems, and the HR function is more strategic.

- HR systems provide seamless and timely support to users throughout the employee life cycle.

- HR systems enable staffing to be achieved in a matter of days, not weeks or more. Succession planning is deliberate and conducted on an enterprise-wide basis.

- A digital employee ID allows a “tell us once” approach where employees provide static HR information and supporting documents once in their career and/or in one place with opportunities to continually auto-populate and update.

- When employees move to another organization, their information is instantly and securely accessible by the new organization. If employees pursue career goals outside of the Public Service their information is retained to enable them to return with the experience and knowledge they have acquired.

- User-friendly and AI-powered systems help employees and managers to get quick answers to HR questions.

- HR systems are reliable, flexible, and adaptable to evolving needs, while maintaining enterprise coherence. They also support interoperability between HR and other enabling functions.

- HR systems easily generate integrated data to support people analytics and decision-making.

- Employees can easily access their own HR data, individual metrics, and AI-based insights (e.g., learning plan suggestions).

- Managers and organizations have access to data that supports workforce management, including real-time business intelligence and predictive data insights (e.g., skills-based data for targeted recruitment).

- Central agencies and central service providers have access to enterprise-wide HR data that supports enterprise decision-making and services, including real-time business intelligence and predictive data insights.

- Disaggregated data is regularly leveraged to understand trends and/or systemic barriers, and to drive actions towards achieving a more inclusive workplace.

- HR decisions leverage multiple sources of evidence to improve outcomes.

- Users have the skills to use HR data to inform their decision-making.

- Experimentation in people enablement is a common practice to generate evidence.

Success Factors – Culture, Change Management, Mindsets and Behaviours

Organizational culture is built on the mindsets, behaviours, and norms that are accepted and reinforced in an organization. To achieve the future of work to which we aspire, effort will be required to develop a culture that aligns with this vision. The importance of an aligned culture cuts across all four imperatives; without it, it may be difficult to reach the full potential that modernization can offer the Public Service.

While the Values and Ethics Code of the Public Service remains the core articulation of our shared values, it is important that the Public Service identify and clearly articulate additional elements of culture that could help us move towards the future of work, including:

- engaging employees regularly to understand evolving needs, gather data, and inform decision-making in order to understand the culture we have, the culture we need, and how to close the gaps.

- sustaining diversity and inclusion efforts, with considerations such as GBA+, official languages, employment equity, and accessibility embedded in every policy, program, and decision point, and to achieve a sense of belonging for all Public Service employees.

- equipping the workforce with the knowledge and skills to adapt to future needs by and incentivizing ongoing learning and professional development to help them to achieve their full potential and deliver results.

- encouraging senior leaders to drive and embody change by aligning incentives that influence culture and reinforcing their team’s culture in key moments such as onboarding, employee recognition, and promotion.

- recognizing that culture is nurtured and maintained through daily interactions and a sense of belonging and contributes to our common purpose to offer the best possible service to Canadians with sound stewardship of public funds.

Conclusion

“The next decade will be one of significant experimentation around work. There is still much to learn about which approaches will be effective. There’s also a large blank canvasfor creative new approaches. But one thing is clear: Firms that doggedly cling to old modes of thinking will struggle to stay relevant.”

The capacity of the Public Service to be more resilient to the shifting trends and emerging crises will rely on its ability to gather evidence, make strategic choices, and support employees through change. When imagining the future Public Service, it is necessary to explore all practices and structures interconnected with people enablement including, for example, digital and real-property elements, not just HR approaches. Some questions to help start thinking about what the future of work could look like include:

- What possibilities listed resonate the most with you/your community?

- What else could be explored, considered, amplified?

- What should be done first?

Wherever the Future of Work leads, implementation should be informed by research, experimentation, and the collection of data to ensure the actions we take are moving us in the direction we want to go. As we experiment with new ways of working and enabling public servants, we will be looking for partners who are interested in testing new approaches and openly sharing the results so we can all learn and move forward together.

Making change in a large organization is a complex process. Implementation of this vision will require the Public Service and its employees to adapt on many fronts including culture, diversity and inclusion, legislation, and internal processes. A dedicated change management strategy will be needed to support public servants and bring about the changes we desire.

This is a once in a generation opportunity for public administration innovation in Canada. Making the most of it will require sustained effort and the participation of all public servants. Doing so will be worth it. Meeting the opportunity with bold actions will increase the ability of the Public Service to nimbly respond to priorities, be resilient to future challenges, and provide a competitive employee experience.

Data Pack

Key information on the public service

In this section

Themes

The Data Pack provides a quick overview and key facts on the Federal Public Service to aid decision makers organized into five key themes

- Expenditures

- People

- Employees

- Executives

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Digital

- Assets and Procurement

- Greening government

- Regulations

This edition

This edition of the Data Pack includes data reflective of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

As a result, data presented here does not represent long-term trends but rather, reflects the significant resources mobilized since March 2020 to support the Government of Canada’s collective emergency response:

- For example, the government’s largest planned statutory expenditure in 2020-21 was $84.4B under the Public Health Events of National Concern Payments Act. This was up from the highest statutory expenditure of $42.2B for Old Age Security payments in 2019-20. In 2021-22, planned statutory expenditures resemble pre-pandemic levels with maximum planned expenditures of $47.2B for Old Age Security payments.

Key Facts

Expenditures

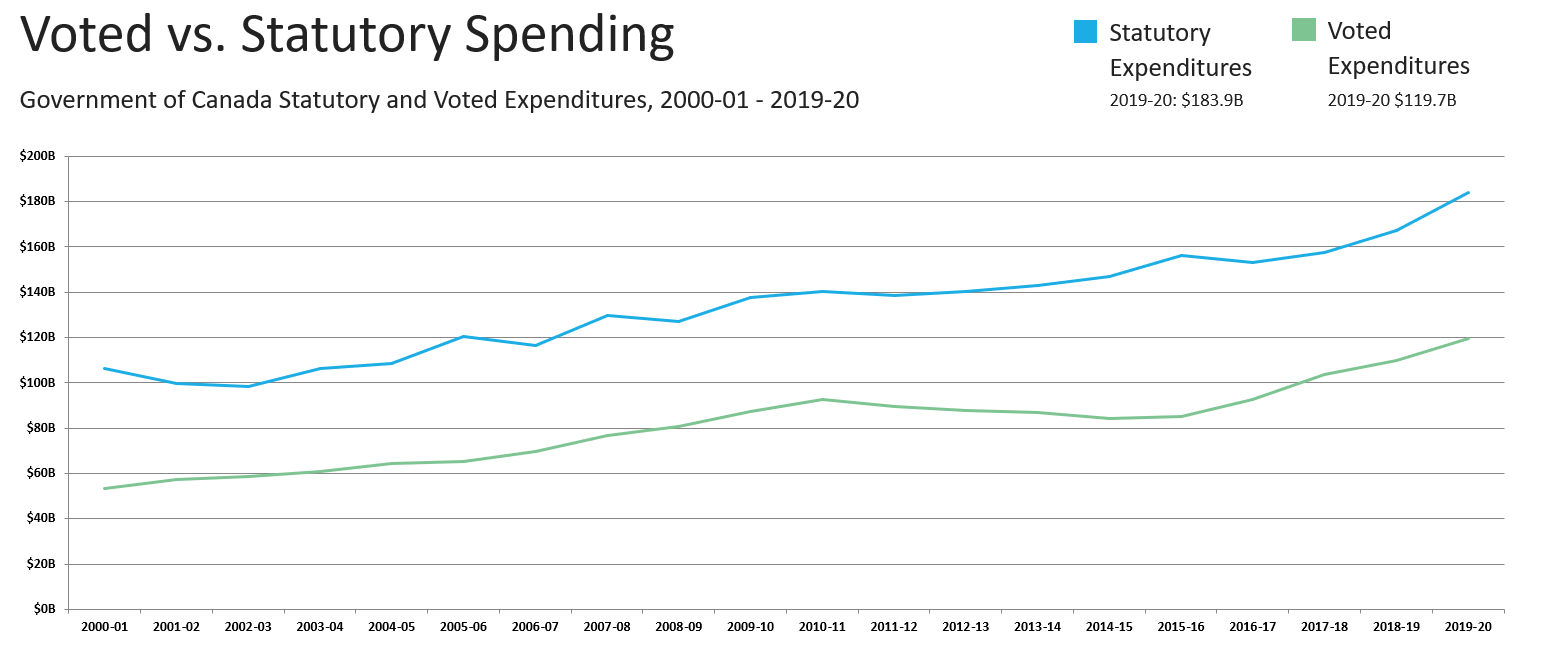

- Voted expenditures have generally risen over time, reaching $119.7B in 2019-20, though expenses have stayed roughly constant as a percentage of GDP (16%)

- Major transfers represent almost half of total government expenses, while other direct program expenses cover another third

- Of the $260.4B in planned 2020-21 statutory expenditures (payments made under legislation previously approved by Parliament), major transfer payments account for 83%

- Planned statutory expenditures increased in 2020-21, from 61% of government spending in 2018-19 to 68% of planned spending in 2020-21. This is largely due to an increase in transfers to persons, as part of the COVID response

People

- The Federal Public Sector is the largest employer in Canada, with 245,739 employees in the Core Public Administration and 73,862 in separate agencies

- The percentage of bilingual positions has increased from 35.7% in 2000 to 42.4% in 2020

- Overall, employment equity representation of women, Indigenous peoples and members of visible minorities across the public service has been improving, but there is much more work to be done. Significant representation gaps persist at executive levels

Digital

- Annual IT operating expenditure for 2019-20 was $7.5B

- The number of Access to Information Requests has steadily increased since 1983, due mainly to a significant increase in requests submitted to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada since 2012-13. Operational costs related to these requests are also rising

- 42% of GC services can be completed on-line from end-to-end

- In 2019-20, internal and external clients completed 425 million transactions (including border crossings) with the Government of Canada

Assets and Procurement

- In 2019-20, the net book value of the Government of Canada’s tangible capital assets was $83.6B

- On a nine-year average, the federal government has awarded $18.5B in contracts annually (over 382,000 contracts)

- As of fiscal year 2019-20, emissions from buildings and conventional fleet have been reduced by 34.6% relative to 2005-06 levels

Regulations

- 150 to 200 proposals for new or amended regulations and 200 to 300 Orders in Council are reviewed and approved annually by Treasury Board

Expenditures - EMS

Organizations in the Government of Canada

| Departments (e.g. Department of Industry) |

22 |

|---|---|

| Special Operating Agencies (e.g. Canadian Coast Guard) |

12 |

| Departmental Agencies Includes 6 Agents of Parliament (e.g. Office of the Auditor General) |

54 |

| Parliamentary Entities (e.g. House of Commons) |

7 |

| Departmental Corporations Includes 3 Service Agencies (e.g. Canada Revenue Agency) |

20 |

| Parent Crown Corporations (e.g. Canada Post Corporation) |

43 |

Figure 5 - Text version

Comparative line graph describing the evolution of voted expenditures and statutory expenditures from the 2000-2001 government fiscal year to the 2019-2020 government fiscal year. The X-axis shows government fiscal year, and the Y-axis shows expenditures in billions.

In 2000-2001, voted expenditures stood at 53.5 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 99.8 billion dollars.

In 2001-2002, voted expenditures stood at 57.1 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 99.8 billion dollars.

In 2002-2003, voted expenditures stood at 58.5 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 98.3 billion dollars.

In 2003-2004, voted expenditures stood at 61.0 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 106.4 billion dollars.

In 2004-2005, voted expenditures stood at 64.2 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 108.6 billion dollars.

In 2005-2006, voted expenditures stood at 65.2 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 120.3 billion dollars.

In 2006-2007, voted expenditures stood at 69.6 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 116.3 billion dollars.

In 2007-2008, voted expenditures stood at 76.6 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 129.7 billion dollars.

In 2008-2009, voted expenditures stood at 80.7 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 127.1 billion dollars.

In 2009-2010, voted expenditures stood at 87.5 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 137.5 billion dollars.

In 2010-2011, voted expenditures stood at 92.6 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 140.4 billion dollars.

In 2011-2012, voted expenditures stood at 89.7 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 138.5 billion dollars.

In 2012-2013, voted expenditures stood at 87.7 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 140.1 billion dollars.

In 2013-2014, voted expenditures stood at 86.9 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 143.1 billion dollars.

In 2014-2015, voted expenditures stood at 84.2 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 147.0 billion dollars.

In 2015-2016, voted expenditures stood at 85.2 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 156.2 billion dollars.

In 2016-2017, voted expenditures stood at 92.8 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 153.2 billion dollars.

In 2017-2018, voted expenditures stood at 103.7 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 157.7 billion dollars.

In 2018-2019, voted expenditures stood at 109.8 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 167.1 billion dollars.

In 2019-2020, voted expenditures stood at 119.7 billion dollars, and statutory expenditures stood at 183.9 billion dollars.

Statutory expenditures represent payments made under legislation previously approved by Parliament. They generally include transfers to other levels of government (e.g. Canada Health Transfer, Fiscal Equalization) and transfers to persons (e.g. Old Age Security).

Voted Expenditures require annual approval from Parliament. They generally include operating and capital requirements of departments and some transfer payment programs.

Source: TBS, December 2020

Breakdown of Statutory Authorities

Of the $217.5B in planned 2021-22 statutory expenditures, major transfer payments account for 68.5%.

Of the 250 statutory items listed as of 2021-22 Supplementary Estimates A, the 10 largest are:

| Organization | Item | Authorities |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Employment and Social Development | Old Age Security payments (Old Age Security Act) | $47.2B |

| Department of Finance | Canada Health Transfer (Part V.1 - Federal-Provincial Fiscal Arrangements Act) | $43.1B |

| Department of Finance | Fiscal Equalization (Part I - Federal-Provincial Fiscal Arrangements Act) | $20.9B |

| Department of Finance | Interest on Unmatured Debt | $16.2B |

| Department of Finance | Canada Social Transfer (Part V.1 - Federal-Provincial Fiscal Arrangements Act) | $15.5B |

| Department of Employment and Social Development | Guaranteed Income Supplement Payments (Old Age Security Act) | $14.6B |

| Department of Employment and Social Development | Payments for the Canada Recovery Benefit pursuant to the Canada Recovery Benefits Act | $12.3B |

| Canada Revenue Agency | Climate Action Incentive Payment | $5.86B |

| Department of Finance | Other Interest Costs | $5.13B |

| Office of Infrastructure of Canada | Contributions related to the Canada Community-Building Fund (Keeping Canada's Economy and Jobs Growing Act) | $4.49B |

| All Other Statutory Items | $32.2B | |

| Total | $217.5B |

Note: Other major transfers to persons included in the Budget forecast but not published in the Estimates include Employment Insurance Benefits (paid from the Employment Insurance Operating Account) and the Canada Child Tax Benefit (paid through the tax system rather than appropriations).

Source: GC InfoBase, June 2021

Breakdown of GC Expenses

GC Expenses in 2019-20, by Type of Programming

Major transfers represent half of total government expenses, while other direct program expenses cover another third.

Direct Program Expenses ($162.8B)

Non-Direct Program Expenses ($210.7B)

Note: Net actuarial losses included under ‘Other Direct Program Expenses’.

Source: Annual Financial Report of the Government of Canada, 2019-20

Net Budgetary Expenditures

Planned statutory expenditures (payments made under legislation previously approved by Parliament) as a proportion of government spending are decreasing, from 60.6% in 2019-20 to 56.7% in 2021-22. Overall government spending is increasing from $303.6B in 2019-20 to $383.4B planned for 2021-22 due to the COVID-19 response.

Parliamentary Authorities

$383.4B as of 2021-22 Supplementary Estimates A

| Voted | Statutory | |

|---|---|---|

| Transfer to Persons | $62.8B | |

| Transfer to Other Levels of Governments | $2.6B | $86.6B |

| Other Transfer Payments | $61.6B | |

| Operating and Other Budgets* | 91.3B | |

| Capital Payments | $10.3B | |

| Other Statutory Payments | $46.7B | |

| Public Debts | $21.3B | |

| Total | $165.8B (43.3%) |

$217.5B (56.7%) |

*Other Budgets include: TB central votes, payments to Crown corporations.

Source: TBS, June 2021

Parliamentary Authorities in 2020-21

$383.4B as of Supplementary Estimates A

Voted: $165.8B, 43.3%

Statutory: $217.5B, 56.7%

Composition of Actual Expenditures, 2019-20

$303.6B as at Public Accounts 2019-20

Voted: $119.7B, 39.4%

Statutory: $183.9B, 60.6%

Figure 6 - Text version

| Year | Authorities Available | Expenditures |

|---|---|---|

| 2000-2001 | $56,281,843,494 | $53,537,319,238 |

| 2001-2002 | $60,112,380,622 | $58,511,725,864 |

| 2002-2003 | $62,100,877,459 | $58,511,725,864 |

| 2003-2004 | $66,469,403,726 | $61,037,036,358 |

| 2004-2005 | $69,592,889,313 | $64,217,385,492 |

| 2005-2006 | $70,379,179,525 | $65,210,027,059 |

| 2006-2007 | $75,825,284,975 | $69,633,087,434 |

| 2007-2008 | $84,635,295,932 | $76,603,718,101 |

| 2008-2009 | $87,343,158,866 | $80,677,910,663 |

| 2009-2010 | $97,629,693,338 | $87,471,108,579 |

| 2010-2011 | $104,281,201,649 | $92,636,171,227 |

| 2011-2012 | $99,894,737,416 | $89,717,871,422 |

| 2012-2013 | $98,646,872,817 | $87,708,965,710 |

| 2013-2014 | $94,753,671,352 | $86,881,410,076 |

| 2014-2015 | $93,954,663,634 | $84,160,464,446 |

| 2015-2016 | $95,358,197,661 | $85,169,699,945 |

| 2016-2017 | $103,671,334,330 | $92,748,873,806 |

| 2017-2018 | $115,035,108,699 | $103,688,179,872 |

| 2018-2019 | $123,594,789,126 | $109,783,245,643 |

| 2019-2020 | $135,125,309,893 | $119,731,891,080 |

* Budgetary authorities and expenditures exclude non-budgetary outlays related to loans, investments and advances.

** Voted authorities and expenditures are approved through supply bills with unused authorities lapsing at the end of the year. They exclude spending that is authorized on a continuing basis through statutes such as the Federal-Provincial Fiscal Arrangements Act or the Employment Insurance Act.

Source: TBS, December 2020

Figure 7 - Text version

| Year | GDP |

|---|---|

| 2000-2001 | 15.8% |

| 2001-2002 | 15.4% |

| 2002-2003 | 15.4% |

| 2003-2004 | 15.3% |

| 2004-2005 | 15.9% |

| 2005-2006 | 14.9% |

| 2006-2007 | 15% |

| 2007-2008 | 15% |

| 2008-2009 | 14.9% |

| 2009-2010 | 17.6% |

| 2010-2011 | 16.5% |

| 2011-2012 | 15.5% |

| 2012-2013 | 15.1% |

| 2013-2014 | 14.6% |

| 2014-2015 | 14.1% |

| 2015-2016 | 14.8% |

| 2016-2017 | 15.3% |

| 2017-2018 | 15.4% |

| 2018-2019 | 15.6% |

| 2019-2020 | 16.2% |

*Expenses are recorded when incurred, as opposed to expenditures which are recorded when the cash is paid. Expenses encompass all spending by the Government of Canada, including direct program expenses, major transfers to people and other levels of government and public debt charges.

Source: Fiscal Reference Tables, 2020

Figure 8 - Text version

Line chart comparing the actual expenditures and authorities from the 2012-2013 government fiscal year to the 2020-2021 government fiscal year. The X-axis shows government fiscal year, and the Y-axis shows actual expenditures and authorities in billions.

In 2012-2013, expenditures stood at 228 billion dollars and authorities stood at 240 billion dollars.

In 2013-2014, expenditures stood at 230 billion dollars and authorities stood at 239 billion dollars.

In 2014-2015, expenditures stood at 231 billion dollars and authorities stood at 243 billion dollars.

In 2015-2016, expenditures stood at 241 billion dollars and authorities stood at 253 billion dollars.

In 2016-2017, expenditures stood at 246 billion dollars and authorities stood at 259 billion dollars.

In 2017-2018, expenditures stood at 261 billion dollars and authorities stood at 275 billion dollars.

In 2018-2019, expenditures stood at 277 billion dollars and authorities stood at 293 billion dollars.

In 2019-2020, expenditures stood at 304 billion dollars and authorities stood at 321 billion dollars.

In 2020-2021, expenditures stood at 440 billion dollars and authorities stood at 475 billion dollars.

In 2021-2022, expenditures stood at 376 billion dollars and authorities stood at 417 billion dollars.

Line chart describing the planned government spending from the 2020-2021 government fiscal year to the 2022-2022 government fiscal year. The X-axis shows government fiscal year, and the Y-axis shows planned spending in billions.

For 2020-2021, planned spending amounts to 305 billion dollars.

For 2021-2022, planned spending amounts to 307 billion dollars.

For 2022-2023, planned spending amounts to 309 billion dollars.

Net budgetary actual authorities and expenditures for all organizations are sourced from the Public Accounts of Canada.

Planned expenditures for most organizations are sourced from Departmental Plans. Where planned spending information is not available (notably for Parliamentary Entities, the Office of the Governor General's Secretary, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, the Communication Security Establishment, the International Joint Commission (Canadian Section) and most Crown Corporations), for illustrative purposes only, the graphic presents these organizations’ 2020-21 Main Estimates figures as being constant across the three planning years.

Source: GC InfoBase, December 2020

Federal Government Compensation

$65.8 billionFootnote 3 Total Federal Government Compensation Costs (2019-20)

Salaries (52%)

Negotiated for unionized and determined by TB for non-unionized

Other Wage Costs (4%)

E.g. overtime, allowances, and premiums. Negotiated for unionized and determined by TB for non-unionized

Benefits (27%)

Includes health and dental care plan, disability and life insurance plans, sick leave, veterans' benefits and RCMP Pensioners' benefits

Pensions (12%)

Excluded from bargaining but consulted upon regularly

Employer Obligations (3%)

E.g. CPP/QPP, EI, Payroll Taxes

Consolidated Crown Corps (3%)

Total personnel costs for consolidated Crown Corporations listed in Public Accounts 2019

Source: TBS, June 2021

Figure 9 - Text version

Comparative line graph describing Government of Canada personnel expenses. The Y-axis shows the dollars in billions, and the X-axis shows the date.

In the 2010 to 2011 fiscal year, personnel expenses were $42,297,102,000 and professional and special services were an additional $7,902,900,000.

In the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year, personnel expenses were $43,837,673,000 and professional and special services were an additional $7,997,818,000.

In the 2012 to 2013 fiscal year, personnel expenses were $46,133,475,000 and professional and special services were an additional $7,513,860,000.

In the 2013 to 2014 fiscal year, personnel expenses were $44,993,653,000 and professional and special services were an additional $7,753,524,000.

In the 2014 to 2015 fiscal year, personnel expenses were $43,810,483,000 and professional and special services were an additional $8,090,232,000.

In the 2015 to 2016 fiscal year, personnel expenses were $50,170,703,000 and professional and special services were an additional $8,353,052,000.

In the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year, personnel expenses were $50,107,857,000 and professional and special services were an additional $9,701,836,000.

In the 2017 to 2018 fiscal year, personnel expenses were $60,293,462,000 and professional and special services were an additional $10,404,283,000.

In the 2018 to 2019 fiscal year, personnel expenses were $57,682,000,000 billions and professional and special services were an additional $11,036,000,000.

In the 2019 to 2020 fiscal year, personnel expenses were $65,793,806,000 and professional and special services were an additional $11,042,332,000.

From 2010-11 to 2019-20, personnel expenses averaged $48.8B. As of 2019-20, personnel expenses were $65.8B.

Personnel expenses include ‘net actuarial losses’ which, as of the 2019-20 Public Accounts, displays this amount separately. In 2019-20, personnel expenses increased to $65.8B from $57.7B in the previous year, largely attributed to higher amortization costs for benefits and pensions.

The approximate 16% average determinate workforce (term, casual, student) and other temporary service (professional and special services) provide some workforce flexibility.

*Data as of June 2021.

Source: Public Accounts of Canada

Internal Services

Internal Services form the “back office”. They are groups of related activities and resources that are administered by the department to support the needs of programs and other corporate obligations. Internal services includes areas such as communications, financial management, human resource management, and information technology.

Internal Services vs. Total Government Spending (2019-20)

The cost of internal services is small (3%) compared to total government spending and remains stable. Total government spending includes services to the public and transfers to provincial and territorial governments.

Non-Internal Services Spending ($294.6B)

Internal Services Spending ($9.0B)

Internal Services vs. Total Operating Expenditures (2019-20)

Internal Services represent approximately 13% of total operating expenditures in 2019-20. Total operating expenditures is the amount government spends on its own operations, and so is smaller than total government spending.

Operating Non-Internal Services Expenditures ($64.4B)

Operating Internal Services Expenditures ($9.4B)

Source: TBS, December 2020

People - OCHRO

Federal Public Sector Profile

Quick facts

The size of the federal public sector is unmatched by any other public or private institution in the country

The Federal Public Service (FPS) contains two distinct populations within the Federal Public Sector:

- the Core Public Administration

- Separate Agencies

Treasury Board as the Employer oversees and approves the HR policies; providing guidance to Deputy Heads in managing the CPA population

Figure 10 - Text version

| 2022 | |

|---|---|

| CPA | 254,309 |

| SA | 81,648 |

| RCMP | 21,678 |

| CAF | 87,632 |

| Crown Corps | 137,327 |

| Total in graph includes minister's staff (758) | 582,594 |

*RCMP public service employees are included in Core Public Administration

Geographic Distribution of the Federal Public Service Workforce

- Yukon

433 Employees (0.1% of total) - Northwest Territories

575 Employees (0.2% of total) - Nunavut

353 Employees (0.1% of total) - British Columbia

27,641 Employees (8.5% of total) - Alberta

18,424 Employees (5.6% of total) - Saskatchewan

6,328 Employees (1.9% of total) - Manitoba

13,065 Employees (4.0% of total) - Ontario (excluding NCR)

45,048 Employees (13.8% of total) - National Capital Region

141,747 Employees (43.3% of total) - Québec (excluding NCR)