Lessons Learned from the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative

Abstract for the report on Lessons Learned from the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative

This report presents the results of a study on the management and implementation of the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative (TPA). The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (the Secretariat) hired Goss Gilroy Inc. (GGI), an independent, third-party firm, to conduct this study on behalf of both the Secretariat and Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC). GGI undertook the study between February and July 2017.

This study is not an audit. GGI’s methodology consisted mainly of consultations to obtain perspectives from across the federal public service. GGI also conducted a document review to understand the context and validate what they heard.

The scope of the lessons learned study covers Government of Canada activities related to the TPA from 2008 to April 2016. The study identifies 17 lessons in 6 major areas:

- Initiative Definition (Lessons 1 and 2)

- Governance and Oversight (Lessons 3 to 5)

- Change Management (Lessons 6 to 8)

- Business Case and Outcomes Management (Lessons 9 to 13)

- Initiative and Project Management (Lessons 14 to 16)

- Capacity Management (Lesson 17)

Although mandated by the Government of Canada, this was an independent study. The opinions and conclusions expressed in this study are therefore solely those of GGI and do not necessarily represent those of the Government of Canada.

View the Government Response to the Independent Report: Lessons Learned from the Transformation of Pay.

Table of contents

- Executive summary

- Acknowledgements

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Background and context

- 3.0 Lessons learned

- 4.0 Conclusions

- List of acronyms

- Glossary

- Appendix A: Timeline of the TPA Initiative

- Appendix B: Methodology for the study of lessons learned

- Appendix C: Government of Canada landscape of IT systems for HR, pay and pensions

Executive summary

Overview of the study

Goss Gilroy Inc. (GGI) was hired by the Internal Audit and Evaluation Bureau (IAEB) at Treasury Board Secretariat on behalf of both Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) and Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) to undertake a lessons learned study for the management and implementation of the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative (TPA). The scope of the lessons learned study covers activities from 2008 to April 2016. The aim of the lessons learned study was to provide a high level, rapid and credible assessment of lessons learned from the management and implementation of the TPA with a view to identifying lessons that may be applied to other current and future federal transformation initiatives. It is important to emphasize that this study reflects the lessons that have been learned based on the information available at this point in time; there may be additional lessons to be learned as the TPA continues to evolve.

This study was undertaken under the broad direction of 2 sponsors, including the Secretary of the Treasury Board and the Deputy Minister of PSPC. However, this was an independent assessment. The GGI study team was given the flexibility and latitude to identify individuals and documents that we felt would be important to consult in order to understand what happened during the management and implementation of the TPA and to identify the lessons learned.

It is important to emphasize that this study is not an audit. Our methodology relied primarily on consultations and utilized documents for context and to validate what we heard from those consultations. The study team approached the work with open minds and sought a high degree of engagement of stakeholders in a confidential environment. Based on a planning phase that included several interviews and a review of documents, GGI designed and implemented a methodology that included a series of almost 40 interviews and 8 half-day workshops involving over 100 individuals. In addition, we consulted and reviewed many different documents from a variety of sources. Every effort was made to obtain the views of all relevant stakeholders in the TPA. Public servants from TBS, PSPC, as well as other departments and agencies were consulted. In all, we spoke with individuals from 39 large and small departments and agencies, with varying relationships to the pay information technology (IT) solution and the Pay Centre. Additionally, the study design sought representation of public servants at all levels of the organization, including employees, compensation advisors, managers, executives and deputy heads. We also consulted many from outside of government including representatives of bargaining agents and private sector entities involved in the TPA. Finally, the study included an in-depth validation phase to ensure that the facts contained in the report are correct and that the views and opinions are appropriately balanced.

Context

The federal government was facing significant pressures related to pay during the early 2000s. An old failing pay system coupled with a compensation advisor community that was facing above-average turnover called for change. The TPA was introduced to address issues with the existing software, the Regional Pay System (RPS), coupled with a consolidated service delivery model in a regional setting.

The TPA was defined as 2 projects: Pay Modernization and Pay Consolidation. Pay Modernization entailed replacing the 40-year-old existing system (RPS) with a commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) option that would be integrated with existing human resources (HR) management systems. Pay Consolidationentailed transferring the pay services of departments and agencies using My Government of Canada Human Resources (My GCHR, an IT system for human resources used in the Government of Canada) to a new Pay Centre (eventually located in Miramichi, New Brunswick).

The compensation environment within the federal government is very complex. It is estimated that the Government of Canada pay system carries out close to 8.9 million annual transactions, valued at approximately $17 billion. In all, the public service is comprised of 22 different employers (such as for the core public administration and for separate agencies) negotiating over 80 collective agreements totaling over 80,000 business rules.

During the timeframe of the TPA (from 2009 to 2016), there were many important contextual factors affecting the environment. These included both cost-saving measures introduced by the Government of Canada as well as several IT-related initiatives (including the creation of Shared Services Canada (SSC) and the development and implementation of My GCHR).

This was a high-risk initiative and the impacts of failure could be extremely significant. Employees could receive incorrect (or no) pay. Also, the reputation of the Government of Canada would be negatively impacted by such a failure. At the time of TPA’s approval in 2009, the Government of Canada had not undertaken a similarly complex transformation with such far-reaching impacts.

The lessons learned

Through the conduct of the lessons learned study, the team identified 17 lessons in 6 areas. The 6 areas are depicted below:

Figure 1 – Text version

This figure shows a series of rectangles to illustrate the flow of the major areas of the lessons learned. There are six major areas and reference to 17 lessons. The figure consists of three large rectangles (left, middle and right), with smaller rectangles inside, each with text. The text in the smaller rectangles shows the title of each of the six major areas and indicates which of the 17 lessons are related to each major area.

In the large rectangle at the left, there are two smaller rectangles, top and bottom. The text in the top smaller rectangle says “Initiative Definition, lessons 1 to 2.” A second smaller rectangle is below, with an arrow pointing down from the top smaller rectangle. The text in the second smaller rectangle says “Governance and Oversight, lessons 3 to 5.”

The middle large rectangle contains one smaller rectangle. This smaller rectangle says “Change Management, lessons 6 to 8.” An arrow points from the large rectangle on the left to the large rectangle in the middle. A two-headed arrow points in both directions from the middle large rectangle to a large rectangle at the right.

In the large rectangle at the right, there are three smaller rectangles at the top, middle and bottom. The top smaller rectangle contains the text “Business Case and Outcomes Management, lessons 9 to 13.” The text in the middle smaller rectangle says “Initiative and Project Management, lessons 14 to 16.” The text in the bottom smaller rectangle says “Capacity Management, lesson 17.” Double-headed arrows are between the top and middle smaller rectangles and between the middle and bottom smaller rectangles.

The flow shows “Initiative Definition” leading to “Governance and Oversight.” These two major areas are the foundation areas and lead to “Change Management,” which is central to all the lessons. “Business Case and Outcomes Management,” “Initiative and Project Management” and “Capacity Management” flow back and forth to each other. These three major areas flow back and forth to “Change Management.”

Two of the 6 major areas were identified as foundational to the overall success of the initiative. The most critical area is the “what” of the transformation (Initiative Definition). This is the big picture of the transformation, the conceiving of all the organizations, business processes, people, and information technology systems that will be involved and will undergo change. This big picture is then broken down into manageable components (usually projects) with a roadmap of how these will all unfold over the years of the transformation. Closely related is the second foundational area, Governance and Oversight, which is the high level “who” of the transformation and ensures that leadership, accountability, decision-making, engagement and oversight are appropriate for the “what” of the transformation.

If these 2 major foundational areas are addressed effectively in the earliest stages of the initiative, the transformation has a greater probability of being successful. The lessons learned from TPA highlight challenges in both Initiative Definition, as well as in Governance and Oversight.

The additional 4 major areas of lessons learned greatly influence the probability of success of the transformation initiative. Each of these major areas is critical to success. They cannot overcome flaws in the 2 major foundational areas, but the lessons learned in these areas are each essential to get right for transformation initiatives.

The lessons within Change Management focus on the “who,” the people involved with and impacted by the transformation initiative. Change Management must surround and underpin the whole initiative and be treated as a fundamental component, being critical for buy-in from those affected by the change, and must support staff and managers to help them adapt to their changing roles.

The lessons within Business Case and Outcomes Management address the “why” of the transformation. The reasons for undertaking the transformation initiative and the outcomes of the transformation (including more than just costs and financial benefits) form commitments that then need to be assessed, adjusted and achieved so that the initial “why” is addressed throughout the transformation and not just at the beginning.

The lessons within Initiative and Project Management area highlight aspects of “how” the transformation initiative and the projects within it are managed day-to-day over the years of the initiative. Although this is a mature area in the literature and there are many experienced practitioners both within and external to the Government of Canada, there are specific lessons learned coming from TPA in this area.

Capacity Management is the final of the major areas and addresses the need to explicitly manage the transformation of the workforce, the “who”, but emphasizing the knowledge and how that knowledge must be stewarded and developed as a critical resource.

The lessons under each of these major areas are:

| Major area of lesson | Lesson learned |

|---|---|

| Initiative Definition | Properly define what is changing Articulate discrete projects and how they interrelate |

| Governance and Oversight | Assign accountability and authority to a single office Establish broad and inclusive governance Ensure oversight provides sufficient challenge |

| Change Management | Assess and then adapt or manage the culture and leadership environment Treat change management as a priority Focus on communications that are effective |

| Business Case and Outcomes Management | Engage and communicate with stakeholders regarding anticipated IT Solution functionality Do not conduct extensive or risky customizations if they can be avoided Implement outcomes management throughout the life of the initiative Do not expect savings until well after implementation Support affected stakeholders if they are to play a role in the initiative |

| Initiative and Project Management | Fully test the IT Solution before launch Leverage and engage the private sector to maximize initiative capacity and capabilities Reassess, learn and adjust |

| Capacity Management | Identify and establish required capacity prior to go-live |

Final thoughts

It is our view, that it was the underestimation of the initiative’s complexity that led to its downfall. Had the initiative been managed recognizing the wide-ranging scope of the transformation, not limited simply to a system replacement or the movement of personnel, then the initiative definition, governance and oversight, change management, outcomes management, project management and capacity management principles underlying the 17 lessons learned could have been established and closely followed.

While the study did not outright assess current Government of Canada capacity/capability to undertake such a transformation, the study team believes that, together, the public service and the private sector possess the correct set of capabilities and capacities to successfully manage and implement such initiatives in the future. However, there is a need to assess how much can be taken on internal to government (given current capacity and capabilities) and to creatively engage the private sector to bring global expertise and to fill the gap in capacity and capabilities. Once the gap in capacity and capabilities is met, then the appropriate initiative definition and governance/ oversight can be put in place to form the foundation for the transformation initiative.

Furthermore, perhaps more important than capacity and capabilities is having the appropriate culture within which to undertake a complex transformation. Agility, openness, and responsiveness are key features of a culture that needs to be aligned with the magnitude and challenge of the transformation.

Finally, in our view, these are lessons that are yet to be learned, not lessons that have been learned through the course of the management and implementation of the TPA. It will be critical for the government to actually apply these lessons in future transformations and more immediately in the transformation challenge currently before the government in addressing the multitude of issues with pay administration today.

Acknowledgements

This study was undertaken by a team of 6 consultants, all of whom brought a unique and valued contribution. Goss Gilroy Inc. would like to thank these team members, including Sandy Moir, Jim Alexander, Dominique Dennery, Steve Mendelsohn, Lauren Evans and Lisa Allison.

The study team would also like to thank those within Treasury Board Secretariat and Public Services and Procurement Canada who supported our work throughout the assignment.

Of course, no study of this kind can be undertaken without the generosity of those who participated in interviews and workshops. Many of those we consulted for the study were asked to provide additional documents, clarification and participate in the validation of the findings. We thank them for their insights and commitment to continuous improvement in their organizations and the Government of Canada as a whole.

1.0 Introduction

Goss Gilroy Inc. (GGI) was hired by the Internal Audit and Evaluation Bureau (IAEB) at Treasury Board Secretariat on behalf of both Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) and Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) to undertake a lessons learned study for the management and implementation of the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative (TPA). The scope of the lessons learned study covers activities from 2008 to April 2016. A summary of the timelines associated with the TPA is presented in Appendix A.

This lessons learned study was launched in late February 2017 and data collection was completed in July 2017.

1.1 Objective of the study

The aim of the lessons learned study was to provide a high level, rapid and credible assessment of lessons learned from the management and implementation of the TPA with a view to identifying lessons that may be applied to other current and future federal transformation initiatives. It is important to emphasize that this study reflects the lessons that have been learned based on the information available at this point in time; there may be additional lessons to be learned as the TPA continues to evolve.

By the term “implementation” we mean the implementation of the TPA Initiative and its 2 main projects, Pay Modernization and Pay Consolidation. The scope of this study goes up to the “go-live” of the information technology (IT) solution (Phoenix) for a total of 290,000 public servants in February and April 2016. Lessons learned relative to the ongoing management of pay administration after April 2016 are outside the scope of this study.

This study was undertaken under the broad direction of 2 sponsors, including the Secretary of the Treasury Board and the Deputy Minister of PSPC. However, this was an independent assessment and, as such, does not necessarily represent the opinions or conclusions of the Government of Canada. The GGI study team was given the flexibility and latitude to identify individuals and documents that we felt would be important to consult in order to understand what happened during the management and implementation of the TPA and to identify the lessons learned. Our main contacts were with the internal audit groups at both TBS and PSPC. Both internal audit groups supported the study team by sending out advanced communications to individuals who we were hoping to consult, by providing access to documents and by supporting us so that we could undertake the project as smoothly as possible. The 2 audit departments were also provided with early drafts of all study deliverables to which they provided comments aimed at clarifying our findings.

It is important to emphasize that this study is not an audit. Our methodology relied primarily on consultations and utilized documents for context and to validate what we heard from those consultations. The study team approached the work with open minds and sought a high degree of engagement of stakeholders in a confidential environment. We were not seeking consensus during our consultations but were seeking input from various perspectives on the observations and issues identified in the discussions, which led to the lessons contained herein.

1.2 Methodology

Based on a planning phase that included several interviews and a review of documents, GGI designed and implemented a methodology that included a series of almost 40 interviews and 8 half-day workshops involving over 100 individuals. We also consulted and reviewed many different documents from a variety of sources (including those that were TPA-focused, Government of Canada-wide and from other jurisdictions and multi-lateral organizations). Appendix B provides more details regarding the methodology for the study.

During the examination phase, every effort was made to obtain the views of all relevant stakeholders in the TPA. Public servants from TBS, PSPC, as well as other departments and agencies were consulted. In all, we spoke with individuals from 39 large and small departments and agencies, with varying relationships to the pay IT solution and the Pay Centre. Additionally, the study design sought representation of public servants at all levels of the organization, including employees, compensation advisors, managers, executives and deputy heads. We also consulted many from outside of government including representatives of bargaining agents and private sector entities involved in the TPA.

In order that the study team was able to properly interpret and categorize the input from the consultations, respondents were directed to focus their comments on areas of the TPA with which they were most familiar and had direct experience.

To conduct the analysis, the study team met several times to discuss and consolidate the main findings and identify the lessons learned. We also reviewed many different Canadian and international reports on leading practices in the conduct of large-scale, complex, IT-enabled transformations. All the lessons contained in this report are based on the consultations and supported with the team’s knowledge of leading practices in these areas.

It was critical for the study to validate the views and opinions of respondents. We did this in 3 ways.

- We tested and validated concepts from documents and early interviews/workshops with subsequent interview respondents.

- As we synthesized and reviewed the results, we sought out areas of agreement and disagreement and identified where opinions were held by many or a few or by only certain types of participants. Any areas of disagreement or confusion were followed up with additional validation through a review of documents and judgment based on our professional expertise and experience. Also during the analysis of the evidence, the team brought their considerable and varied experiences to help interpret what we heard and to apply known leading practices.

- We shared preliminary findings with Departmental Audit Committees for TBS and PSPC and also conducted 5 targeted in-person follow-up interviews with individuals (all but 1 of whom had provided input during the examination phase). We chose these 5 individuals for their knowledge of the management and implementation of TPA and for their differing perspectives and experience with TPA.

2.0 Background and context

2.1 The issue

In fall 2007, the Minister of Public Works and Government Services proposed to implement a new Government of Canada pay system to address issues with the existing software, the Regional Pay System (RPS). The Minister of Public Works and Government Services subsequently brought forward an “Initiative to Fix the Pay System” as a response to a number of human resources and pay-related issues in the public service. The initiative was approved in June 2009 and then in July 2009 to define both the new Government of Canada pay system and the consolidated service delivery model.

Transforming the pay system of the public service is no small task. At the time, Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC) (renamed as Public Services and Procurement Canada in 2015) administered pay for over 100 departments and Crown Corporations which represented almost 300,000 employees.Footnote 1 The Government of Canada pay system carried out close to 8.9 million annual transactions, valued at approximately $17 billion.Footnote 2 In all, the public service is comprised of 22 different employers negotiating approximately 80 collective agreements totaling over 80,000Footnote 3 business rules. CompensationFootnote 4 across the public service is also regulated through federal legislation including the Financial Administration Act, the Public Service Employment Act, the Public Service Superannuation Act, the Public Sector Equitable Compensation Act, the Federal Public Service Labour Relations Act and the Government Employees Compensation Act.

The RPS used by PWGSC and departments was severely outdated, ineffective and cost-inefficient.Footnote 5 The demand for flexible and reliable pay services was increasing at the time,Footnote 6 and benchmarking against other organizations showed that the system was performing poorly compared to similar infrastructures.Footnote 7 Also, the system’s maintenance was labour-intensive and depended on the specialized knowledge and experience of IT and compensation staff with high attrition rates.Footnote 8Footnote 9 This was further complicated by compensation advisors frequently transitioning among departments in the National Capital Region.Footnote 10

Moreover, there was a lack of integration between RPS and the multiple Human Resources Management Systems (HRMS) used throughout the public service. It was almost impossible to effectively monitor the overall pay administration due to its fragmentation. The problems associated with the pay system were also described in the Auditor General’s spring 2010 report on the effective functioning of government, which contains 1 chapter on the Aging Information Technology Systems within the public service.Footnote 11 The audit, which examined 5 departments with high IT expenditures, highlighted significant risks associated with the old pay IT infrastructure “at risk of breaking down.” Such a technical failure could significantly disrupt the activities of these organizations. The report mentions that PWGSC had included the precarious state of the outdated system in its corporate risk profile, describing it as “close to imminent collapse.”

The TPA Initiative was designed to address these overlapping issues. TPA was articulated to mesh with other public service modernization projects, including the Back Office Systems Modernization and the Greening Government Initiative.Footnote 12 In addition, it was aligned with ongoing commitments to increase effectiveness and innovation in the public service, as outlined in the 2008 Speech from the Throne. The initiative was also responding to the recommendations of the Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates, which issued a spring 2008 report underlining problems in the Pay and Benefits community. The initiative was to support modernization and increase stability in the compensation workforce.Footnote 13

2.2 The initiative

The TPA Initiative received Government of Canada approval in 2009.Footnote 14 In 2010, the Prime Minister announced that pay services would be consolidated in Miramichi, New Brunswick. This would bring economic benefit to the region. The initiative had 2 distinct but related components: Pay Modernization and Pay Consolidation. The overall objective of this initiative was to ensure the long term sustainability of federal pay administration and services.

The Pay Modernization Project of TPA entailed replacing the 40-year-old existing pay system (RPS) with a commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) option. The new IT solution would be integrated with the Government of Canada’s HRMS. The COTS option (coupled with the Pay Consolidation project, described below) was selected as the option offering the highest ongoing annual cost savings and the best risk mitigation, compared to other options of upgrading the system or outsourcing pay services altogether. Overall, moving to a COTS solution was meant to increase the sustainability and adaptability of pay administration, allow for government-wide integration of systems, increase the capabilities of managers and employees for self-service, contribute to the TBS Public Service Modernization agenda, improve business intelligence and reporting, and increase efficiency.

In an attempt to reduce costs, improve services, stabilize the workforce and minimize turnover of compensation advisors, the Consolidation of Pay Services Project (referred to in this report as Pay Consolidation) entailed transferring the pay services of departments and agencies to a new Public Service Pay Centre located in a single region outside the National Capital Region. The decision to locate the new Pay Centre in Miramichi, New Brunswick, was made in 2010, with the decision highlighting the promise to replace jobs lost by the closing of the Firearms Centre and the Prime Minister noting that the “payroll centre move will absorb any job losses in the firearms centre "many times over.”Footnote 15 The Pay Centre opened in March 2012.

The Pay Consolidation component of TPA had 2 phases: the objective of Phase I was to have the Pay Centre manage an initial 184,000 pay accounts associated with those departments using “the current government HR standard” (PeopleSoft, branded for the Government of Canada as My GCHR, described below), accounting for about 68% of federal departments/agencies. These pay accounts were to be transferred in 3 waves. The first phase also included establishing partnerships with community colleges in relatively close proximity to Miramichi for compensation-related training to ensure a supply of compensation advisors for the Pay Centre. Phase II, which will consolidate pay services for all the remaining departments/agencies, will be implemented in the future as a separate initiative (as of the writing of this report, Phase II has not yet begun).

In 2009, the cost for Pay Modernization was estimated at $192.1 million and Pay Consolidation at $106.1 million, for a grand total of $298.2 million for TPA. In 2012, the cost of Pay Modernization was re-evaluated at $186.6 million and Pay Consolidation at $122.9 million, for a new total cost of $309.5 million.Footnote 16

It was estimated that TPA would generate significant savings from a number of sources, including economies of scale, integration, self-service capabilities and automation, as illustrated below in Table 1. A 2012 update included a small adjustment in savings (in the amount of $1 million).Footnote 17

| Area of savings | Amount (2009) | Amount (2012 update) |

|---|---|---|

| Modernization: due to self-service | $46.9M | $17.6M |

| Modernization: due to other automation | $6.7M | $14.4M |

| Consolidation only: due to economies of scale | $11.8M | $10.8 M |

| Consolidation with modernization: due to efficiencies gained in the consolidated service environment once the modernized pay system is operational | $13.7M | $35.3M |

| Total | $79.1M | $78.1M |

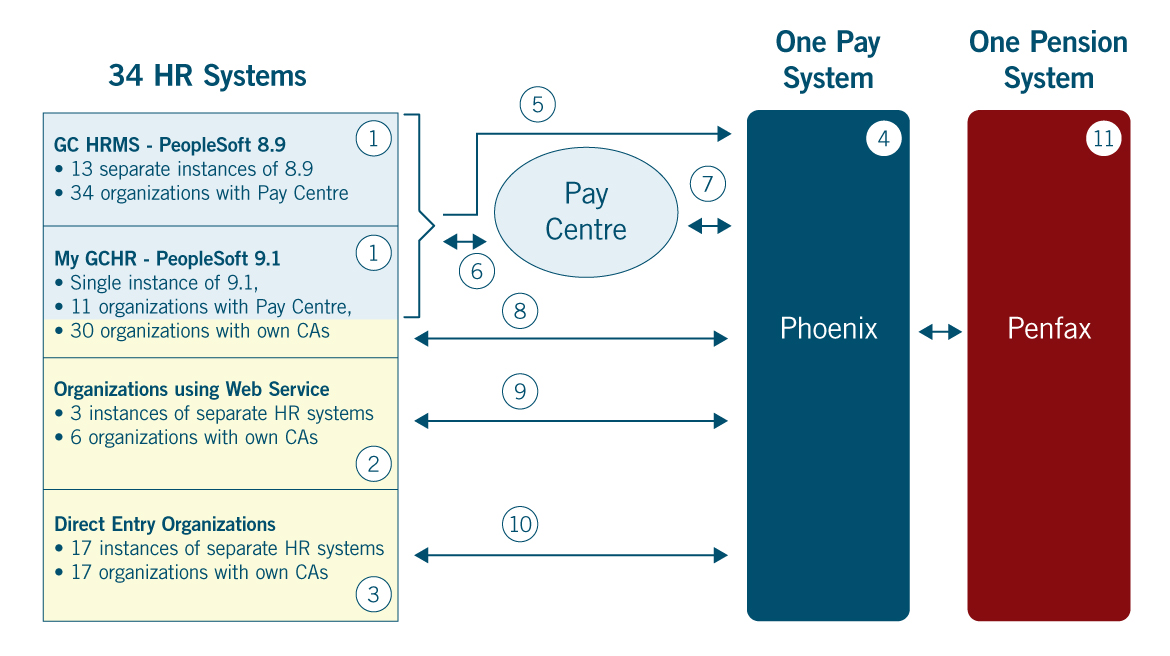

Once launched, 98 departments and agencies would have their pay administered by Phoenix. Of those, 45 departments and agencies would be serviced by compensation advisors located at the Pay Centre and the remaining 53 departments and agencies would continue to have compensation advisors within their organizations. Of these 53 departments and agencies, 30 were using PeopleSoft 9.1, 17 used direct entry to Phoenix and 6 used the web service to access Phoenix. Appendix C presents this information graphically.

2.3 Context

The Government of Canada is a large and complex organization. There were (and remain) many important contextual factors that influenced the design, management and implementation of the TPA. These include the government’s model for accountability, as well as initiatives that were introduced during the timeframe of the TPA, such as cost-saving measures and other IT-related initiatives that would impact the environment within which the TPA was unfolding. These contextual factors are described below.

Government of Canada model for accountability

Under the Westminster model of government, deputy heads are professional, non-partisan public servants positioned at the head of departments and agencies. They are selected by the Prime Minister on the advice of the Clerk of the Privy Council, and appointed by the Governor in Council through an Order in Council. Deputy heads serve as expert advisors to their respective Ministers, and are in charge of day-to-day management of their department on behalf of the Minister. Deputy heads are accountable to multiple parties.Footnote 18 They are accountable to their Minister in the exercise of their duties, but also to the Prime Minister through the Clerk of the Privy Council on matters that are of importance to the collective management of the government. Deputy heads are also accountable to Treasury Board for the management and performance of their respective departmentsFootnote 19 and to other central agencies with regards to the powers entrusted in them (which include management of human resources). However, in this model of accountability, a degree of ambiguity remains with regards to who is responsible for the implementation of government-wide initiatives.

More specifically pertaining to people management, deputy heads have primary responsibility for the effective management of the people in their organizations. They are responsible for planning and implementing people management practices that deliver on their operational objectives and for assessing their organization’s people management performance. One of the people management practice principles is “An effective people management information infrastructure supports business success and accountabilities.”Footnote 20

As a central agency, TBS is the administrative arm of the Treasury Board, and the President of the Treasury Board is the Minister responsible for TBS. TBS supports the Treasury Board by making recommendations and providing advice on program spending, regulations and management policies and directives, while respecting the primary responsibility of deputy heads in managing their organizations, and their roles as accounting officers before Parliament. The Treasury Board oversees the government’s financial, human resources and administrative responsibilities, and establishes policies that govern each of these areas. The Treasury Board, as the management board for the government, has 3 principal roles. It acts as:

- the government’s Management Office by promoting improved management performance

- the government’s Budget Office by examining and approving the proposed spending plans of government departments and by reviewing the development of approved programs

- the human resources office and employer or People Management Office by managing compensation and labour relations for the core public administrationFootnote 21

Organizationally, there are 3 broad areas within TBS, namely the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (OCHRO), the Office of the Comptroller General (OCG), and the challenge function (including Program Sectors and policy centres such as the Chief Information Officer Branch (CIOB)). OCHRO’s responsibilities include the management of compensation, including compensation planning and reporting, collective bargaining, establishing the collective agreements, establishing the common business processes for people management, and the management of HR-related functional communities (with the compensation advisor community as a particularly relevant community for the transformation of pay administration). The OCG’s responsibilities include monitoring, providing guidance and recommending corrective actions regarding financial management performance of departments and agencies and providing advice on control frameworks for financial management (with compensation being a large component of the operating expenditures of governmentFootnote 22). The challenge function or due diligence of TBS involves cost validation, assessment of risk, alignment to current priorities and sound advice on submissions in the overall role of general manager of the federal public service.Footnote 23 The challenge function draws heavily upon the various Treasury Board policy areas of the Government of Canada including not only Information and Technology, but also areas such as Risk, Assets and Acquired Services, Financial Management, Compensation, and People Management.Footnote 24 The Information Technology Project Review and Oversight Division (ITPROD), a group within CIOB at TBS, has a mandate for the oversight of a select portfolio of high-risk or complex IT-enabled projects within the Government of Canada.

In terms of service provision, under the Treasury Board Common Services Policy, PSPC (formerly PWGSC) is identified as a common service organization with compensation being identified as a mandatory service for which departments and agencies must use PSPC as the common service provider.

In terms of accountabilities regarding compensation, the Department of Public Works and Government Services Act requires the department to provide such administrative and other services required for the disbursement of pay, employee benefit plans and superannuation or pension plans to persons employed in or by any department, and to persons employed in or by other portions of the federal public administration, as the Governor in Council may direct. Moreover, as directed by the Act, by Order in Council, the Pay Disbursement Administrative Services Order (2011) repeals the 1981 Order and states (in part) that the Minister of the department shall provide services required for the disbursement of pay including the verification of payment requisition certification, the development, operation and maintenance of a pay processing system and take all necessary steps with respect to pay administration to initiate, change or terminate pay based on personal employee information and pertinent personnel documentation.

Cost saving measures

Around the time the TPA was launched, the government was actively pursuing a range of cost-reduction objectives. The 2010 and 2011 Budgets reflected an intention to reduce government spending, namely by having Treasury Board carefully manage department growth and freezing operating budgets to 2010 to 2011 levels. The 2011 and 2012 Budgets, building on 4 rounds of reviews initiated in 2007 to improve management of government spending, introduced a 1-year Strategic and Operating Review spearheaded by Treasury Board (in 2011) and a comprehensive Deficit Reduction Action Plan (in 2012). The goal of these measures was to achieve at least $4 billion in ongoing savings by fiscal year 2014 to 2015 (or 5% of the review base).Footnote 25 The Strategic and Operating Review covered 67 departments and organizations representing about $80 billion of direct program spending.Footnote 26 The Deficit Reduction Action Plan also entailed generating ongoing savings of 5% to 10%Footnote 27 of direct program and operations spending through increased efficiencies in departments and agencies.

Other contextual factors

At the time TPA was launched, each department managed its own technological resources and related budget, which resulted in a decentralized and uneven IT landscape across the public service. In order to remedy the obsolescence of IT systems in the public administration, the Government announced in 2011 the creation of Shared Services Canada (SSC), a new organization which was charged with modernizing, standardizing and consolidating IT resources across 43 departments. The initiative aimed to reduce costs by updating the technological structure and centralizing IT staff and budgets within SSC. SSC’s broad mandate includes reducing the number of data centres from almost 500 to 7,Footnote 28 consolidating and securing 50 overlapping networks, and ensuring all emails are managed through a single common infrastructure, among other commitments. SSC also equips departments and agencies with updated hardware (for example, voice over the internet for phones, video-conference, wifi).

The Human Resources Services Modernization (HRSM) initiative was launched by TBS in 2011. The objective was to modernize human resources (HR) services in departments to reduce the number of HR systems to support 1 process, 1 system and 1 data set for the Government of Canada, leading to efficiencies for transactional HR activities. The HRSM initiative included several components, but of particular relevance to TPA was the implementation of Common HR Business Processes (CHRBP). The CHRBP, led by OCHRO, was meant to “bring consistency to the delivery and management of HR services in all government organizations.”Footnote 29 There is no reference to alignment with pay systems or processes in the foundational CHRBP documentation. The implementation of CHRBP entailed that organizations would analyze and report on their departmental HR practices based on the new business process, and would then identify, prioritize and implement actions to ensure their alignment with the CHRBP. This synchronization process was deemed by OCHRO to be completed by March 31, 2014. However, an evaluation of the HRSM initiative in 2016 found that, while all participating departments and agencies indicated they had implemented CHRBP, a few of those consulted for the evaluation did not feel their organization had fully adopted CHRBP and that their organization continued to use previous processes (especially pertaining to the roles continuing to be carried out by HR personnel rather than managers, with the establishment of “shadow” HR units).Footnote 30 Moreover, the evaluation raised concerns that the CHRBP was not implemented to a sufficiently detailed level in order to ensure government-wide consistency for IT-systems and data and found that there was a continuing need to implement processes at a more detailed level.Footnote 31

My GCHR, introduced in 2015, is the Government of Canada-branded version of a PeopleSoft 9.1 Human Resources Management System, which, with onboarding taking place over many yearsFootnote 32 is meant to replace the over 70 different HR systems that were in use across the Government of Canada.Footnote 33 The synchronization to this new platform is meant to increase automation, standardize and streamline HR processes across departments, increase self-service options, and facilitate information sharing.Footnote 34 As of June 2017, My GCHR was only introduced in 44-organizations and there are an additional 31-different-HR systems remaining in departments and agencies.

Appendix C presents the landscape of the various HR-systems that operated within the Government of Canada at the time of the launch of Phoenix in 2016. It illustrates the various systems and interfaces required of the new pay IT-solution at launch.

3.0 Lessons learned

Through the analysis of the consultations and documents, the study team has identified 6 major areas of lessons learned containing a total of 17 lessons. The 6 major areas are presented in Figure 1, as follows:

- Initiative Definition (Lessons 1 and 2)

- Governance and Oversight (Lessons 3 to 5)

- Change Management (Lessons 6 to 8)

- Business Case and Outcomes Management (Lessons 9 to 13)

- Initiative and Project Management (Lessons 14 to 16)

- Capacity Management (Lesson 17)

In our view, these are lessons that are yet to be learned, not lessons that have been learned through the course of the management and implementation of the TPA.

Two of the 6 major areas were identified as foundational to the overall success of the initiative. The most critical area is the “what” of the transformation (Initiative Definition). This is the big picture of the transformation, the conceiving of all the organizations, business processes, people, and information technology systems that will be involved and will undergo change. This big picture is then broken down into manageable components (usually projects) with a roadmap of how these will all unfold over the years of the transformation. Closely related is the second foundational area, Governance and Oversight, which is the high level “who” of the transformation and ensures that leadership, accountability, decision-making, engagement and oversight are appropriate for the “what” of the transformation.

If these 2 major foundational areas are addressed effectively in the earliest stages of the initiative, the transformation has a greater probability of being successful. The lessons learned from TPA highlight challenges in both Initiative Definition, as well as in Governance and Oversight.

The additional 4 major areas of lessons learned greatly influence the probability of success of the transformation initiative. Each of these major areas is critical to success. They cannot overcome flaws in the 2 major foundational areas, but the lessons learned in these areas are each essential to get right for transformation initiatives.

The lessons within Change Management also focus on the “who,” in terms of the people involved with and impacted by the transformation initiative. Change Management must surround and underpin the whole initiative and be treated as a fundamental component, being critical for buy-in from those affected by the change, and must support staff and managers to help them adapt to their changing roles.

The lessons within Business Case and Outcomes Management address the “why” of the transformation. The reasons for undertaking the transformation initiative and the outcomes of the transformation (including more than just costs and financial benefits) form commitments that then need to be assessed, adjusted and achieved so that the initial “why” is addressed throughout the transformation and not just at the beginning.

The lessons within the Initiative and Project Management area highlight aspects of “how” the transformation initiative and the projects within it are managed day-to-day over the years of the initiative. Although this is a mature area in the literature and there are many experienced practitioners both within and external to the Government of Canada, there are specific lessons learned coming from TPA in this area.

Capacity Management is the final of the major areas and addresses the need to explicitly manage the transformation of the workforce, the “who”, but emphasizing the knowledge and how that knowledge must be stewarded and developed as a critical resource.

The lessons under each of these major areas are described below.

3.1 Initiative definition

Scoping: Properly define what is changing

A Target Operating Model construct as illustrated in Figure 2 indicates the scope of areas to be considered in any transformation initiative.

Figure 2 – Text version

This figure consists of a series of hexagons that is based on a model for the finance function developed by KPMG. There is one large hexagon in the background. Centred on each of the six sides of the large hexagon’s perimeter is a smaller hexagon. There is one small hexagon in the centre that contains text. Each hexagon on the large hexagon’s perimeter contains text that describes the six aspects of a model for the finance function.

The hexagon in the centre contains the text “Federal Pay Operating Model.” Centred above it, the first smaller hexagon contains the text “Services, Functions and Processes.” Moving in a clockwise direction, the next five hexagons each contain text that describes another aspect. They are “Technology,” “Organization and Governance,” “Clients,” “Performance Management” and “People and Skills.”

Lesson 1

Define the scope of areas undergoing change and define the changes as discrete projects with associated interrelationships and interdependencies within the overall initiative.

While each of the areas in this model was actually undergoing change as part of the TPA, the focus was almost wholly confined to the management of technology (the Pay Modernization project pertaining to development a new IT solution) and of organization (the Pay Consolidation project pertaining to the downsizing of the compensation advisors and establishment of the Pay Centre).

However, the initiative implicated much more than these 2 aspects. The TPA Initiative was complex, broad, and highly dependent on the ability of a wide range of users to prepare for the transition, and adapt and change the way they carried out their HR and pay activities. While TPA documentation frequently referred to the complexity associated with the processes and business rules for pay, most of those consulted for the study admitted that very few people (other than compensation advisors) understood the degree of complexity associated with the day-to-day requirements to ensure accurate pay. The complexity of the HR to Pay process and how it would be transformed may have been understood in segments or silos but the overall management of the end-to-end process transformation from, for example entering HR data for an initial hiring offer, to the regular entry of overtime or other compensation actions, to paying employees and benefit providers (through an overall process ownerFootnote 36) did not appear to be in place.

Business processes, people/skills (including compensation advisors, others working in HR and managers with HR responsibilities), all users of the new IT solution (that is, all public servants), organizational culture, services and functions (for example, the transforming of the roles of managers and HR professionals in departments and agencies), quality and timely provision of HR data and related HR systems were also very significant areas of change in this initiative. While some of these other aspects were mentioned in the early documentation (PWGSC’s Report on Plans and Priorities for the 2010 to 2011 fiscal year that briefly discussed business processes), it was only in passing and no comprehensive plan for transformation was implemented.

Cutting across all these elements was the establishment of a new service model for the administration of pay. Where before departments and agencies had compensation advisors internal to their organizations, these positions became centralized at PSPC for 45 departments and agencies.Footnote 37 However, the design of this service model (including culture, service standards, roles and responsibilities, governance, processes) did not address the full scope of the changes end-to-end across HR to Pay that would be required within individual departments and agencies, nor did the development of the service model fully address the diversity of practices within all departments and agencies.

To further illustrate the complexity of the environment within which the Government of Canada administers its pay and the resulting impact of this environment on the performance of pay under RPS, a benchmarking analysis undertaken by IBM compared the Government of Canada pay administration performance with industry performance in the areas of cost, efficiency and quality, and cycle time.Footnote 38 This study confirmed the complexity of the environment within which pay is administered in the Government of Canada and suggests that this complexity should have been addressed (at least in part) prior to implementing a new IT solution.

Thus, additional discrete projects (scoped and funded and with assigned accountability) were needed to address all aspects of change per the operating model. Some examples of these additional projects include:

- implementing new business processes (and controls) in departments and agencies to be carried out by those in HR (including compensation advisors) and by managers (such as CHRBP, but to a greater level of detail and fully implemented by departments and agencies)

- implementing changes to existing HR systems and introducing new HR systems (such as My GCHR)

- implementing an HR to Pay performance management framework, including benchmarking key service, efficiency and quality performance metrics for the original pay administration environment so that the performance of the new pay administration environment using Phoenix (by all departments and agencies) could be properly understood and tracked

- addressing the cultural aspects at play such as the resistance to changing long-established practices such as carrying out most HR transactions retroactively, which has contributed to substantial backlog of pay transaction (as outlined below under Lesson 9)

Roadmap: Articulate discrete projects and how they interrelate

When considering implementing a complex initiative, a roadmap is a high level description (which can be a graphic, a table or narrative) of the various components of the projects, along with the schedule, deliverables and interrelationships.Footnote 39 Leading practice suggests that a roadmap should be developed that is based on the discrete components that fully account for the proposed changes to all aspects of the operating model, as well as related projects.

The roadmap encourages project managers to see how each part of the project (or in this case, each discrete project in the TPA Initiative) ties to:

- initiative objectives

- timeline

- deliverables

- risks

- interdependences and interrelationships

Lesson 2

Develop a roadmap to articulate the interrelationships and interdependencies between the discrete projects within the defined scope of the transformation initiative (as well as with other related projects).

The roadmap is a tool whereby each of the discrete projects would then be considered holistically. This would include not only project management, but when and how the concepts of change management and risk management would be brought in. It is the view of the study team that if the various discrete projects had been considered as a whole, the interrelationships and interdependencies would have been identified and could have been better managed and associated risks better mitigated.

Even in the absence of the identification of all the various discrete projects, a more holistic and inclusive approach to project, change and risk management would have addressed many of the issues encountered throughout the TPA lifecycle. Indeed, if a roadmap had been outlined, then a better staging of the various components could have been undertaken. The study team suggests that the staging of the components could have been:

- the business processes within PSPC and also within departments and agencies pertaining to HR to Pay (including roles and responsibilities with respect to approvals) should have been examined and changed/fully implemented first. This would have included training managers on their HR responsibilities and any of their changed roles, including those pertaining to Section 34Footnote 40 of the Financial Administration Act

- next, new or updated HR systems would have been implemented (ideally based on a common configuration of PeopleSoft across most departments and agencies) and the quality of HR data addressed in a systematic way in all organizations

- this would have been followed by the build of a new pay system based on the new business processes and on the common HR system implemented, along with the training on the new system of an experienced compensation workforce. Reduction of the number of compensation advisors could be managed based on efficiencies within the new pay system

- the last part of the transformation would have been the relocation of compensation advisors to a more centralized delivery model

3.2 Governance and oversight

Accountability: Assign accountability and authority to a single office

Accountability is a relationship based on obligations to demonstrate, review, and take responsibility for performance, both the results achieved in light of agreed expectations and the means used. The principles of effective accountability are outlined below.Footnote 41

Clear roles and responsibilities |

The roles and responsibilities of the parties in the accountability relationship should be well understood and agreed upon. |

|---|---|

Clear performance expectations |

The objectives pursued, the accomplishments expected, and the operating constraints to be respected (including means used) should be explicit, understood, and agreed upon. |

Balanced expectations and capacities |

Performance expectations should be clearly linked to and balanced with each party’s capacity (authorities, skills, and resources) to deliver. |

Credible reporting |

Credible and timely information should be reported to demonstrate what has been achieved, whether the means used were appropriate, and what has been learned. |

Reasonable review and adjustment |

Fair and informed review and feedback on performance should be carried out by the parties, achievements and difficulties recognized, appropriate corrections made, and appropriate consequences for individuals carried out. |

Lesson 3

Assign accountability and authority for a multi-department/agency or government-wide transformation initiative to a single minister and deputy head, with the accountabilities, authorities, roles and responsibilities of other implicated organizations being designed, documented and implemented as part of an overall accountability framework.

From the perspective of roles and responsibilities, as noted previously in Lesson 1, the overall undertaking within the Government of Canada to transform the compensation environment was shaped by reducing of the scope of the transformation to be simply the 2 projects under the TPA. Accountability for both projects under the TPA (that is, Pay Modernization and Pay Consolidation) was assigned to PSPC. As noted previously, its roles and responsibilities as the overall lead were sought by the Minister of Public Works and Government Services in 2009, and granted, following the normal challenge process of the TBS.

However, as noted in Lesson 1, the actual scope of the undertaking to transform the compensation environment, which involved much more than these 2 projects, was not well understood. One result of the too-narrow scope was an incomplete accountability framework for the transformation. The roles and responsibilities of additional parties with accountabilities for the broader areas (namely TBS along with departments and agencies) were not effectively designed, documented nor implemented as part of an overall accountability framework.

An important party in the transformation of the compensation environment was the deputy head community responsible for leading affected departments and agencies. Deputy heads are accountable for their own organizations and therefore, for the implementation of TPA within their organizations. However, the study team learned that most deputy heads were not aware of most of their responsibilities with respect to the TPA, particularly ensuring new business processes introduced by the CHRBP initiative were fully understood and implemented, and also implementing change management more broadly. Moreover, most deputy heads did not realize the extent of the changes being introduced by the initiative and the corresponding risks to their organization and to their employees’ pay. Reasons for this varied but the most commonly mentioned factor was that there were many change initiatives underway at the time and TPA was not identified to deputy heads as being more important than any other. Also, briefings provided by PSPC throughout the initiative were generally positive and, other than raising concerns on the need to ensure HR data was accurate, did not raise any red flags or other reasons to warrant more deputy head attention.

Another principle of effective accountability is that of balanced expectations and capabilities; that is that performance expectations should be clearly linked to and balanced with each party’s capacity (authorities, skills, knowledge and resources) to deliver. PSPC sought and was granted the accountability to carry out both projects on behalf of the Government of Canada. However, it did not appear that the authority to ensure that the full scope of changes to occur throughout the whole of the Government of Canada was either recognized as being needed nor was it given to or assumed by any one organization. So although PSPC had the accountability to deliver on TPA, neither PSPC nor any other organization was able to exercise the necessary authority to make this happen.

With PSPC not being able to exercise the overall authority (neither at the deputy minister nor ministerial level) over the full scope of the transformation of the compensation environment, the senior coordinating body for the transformation success appeared to fall to the Public Service Management Advisory Committee (PSMAC).Footnote 42 PSMAC regularly received updates on TPA and even served as a sounding board for deputy head concerns about the project; however, the committee could not be accountable for the initiative. No one individual or governance body was assigned the authority to ensure the necessary steps were being taken to ensure the overall success of the initiative.

In a government-wide initiative such as the transformation of compensation, it is clear that an effective and comprehensive accountability framework should explicitly include the authorities and roles of TBS, departments and agencies, as well as of any organizations leading specific projects within the initiative. The accountability framework should also clearly state where the overall accountability rests for the full scope of the transformation initiative. This overall accountability should be specified at both the ministerial and deputy head level.

The actual selection of the appropriate minister, deputy head and organization for overall accountability is complex and would likely depend on the particular transformation initiative. At the moment, it does not appear that any one organization has the necessary accountability, authority and capabilities to carry out such a role in future transformations. Given that these could be adjusted, one possibility to consider would be TBS, given its “general manager” role.Footnote 43 It could assume the overall accountability for such government-wide transformation initiatives. Other possibilities could be a lead client department/agency or the department/agency leading the major project(s) within the initiative. In each case, accountabilities, authorities and capabilities would need to be addressed.

Governance: Establish broad and inclusive governance

Governance refers to how an organization makes and implements decisions.Footnote 44 Governance is complex and fluid and complicated by the fact that it involves multiple actors who are the organization’s stakeholders. They articulate their interests, influence how decisions are made, who the decision-makers are and what decisions are made. Decision-makers must consider this input and are then accountable to those same stakeholders for the organization’s output and the process of producing it.Footnote 45

Lesson 4

Establish governance that fully reflects the broad range of stakeholders affected by the entire initiative. For example, a committee with membership from the end-to-end process owner, the organization(s) leading projects, and different types of stakeholders (such as departments/agencies, representatives of affected functional communities and policy centres) should oversee the initiative.

According to documentation received from PSPC during the lessons learned study, the Pay Modernization project included the following governance mechanisms:

- Senior Project Advisory Committee (SPAC)

- Risk Management Oversight Committee (RMOC)

- Executive Management Team

- Change Agent Network

- External Advisory Committee

- TPA Union Management Committee (TPAUMC)

The initiative’s governance (and decision-making) was led by PSPC but did not reflect the full scope of the areas undergoing change in the initiative. In particular, most governance was focused on the Pay Modernization project rather than the Pay Consolidation project. Documentation from PSPC indicates that the Pay Modernization governance bodies (SPAC and RMOC) received Pay Consolidation updates starting in fall of 2013. Thus, there was really no overall governance body for the TPA as a whole. Such an overall governance body, established at the outset of the initiative, should have had participation from PSPC, various players at TBS (such as OCG and OCHRO) and departments and agencies.

One of the key gaps in the governance structure was the lack of decision-making involvement of an HR to Pay process owner. Leading practice would suggest that there should be a defined accountability for the end-to-end process, in this case the HR to Pay compensation process and that this process owner should be part of governance. The SPAC and RMOC, being only advisory bodies and being focused almost exclusively on the Pay Modernization project did not fully consider the HR to Pay process. While all those consulted for the study agreed that PSPC was not the HR to Pay process owner, there was little consensus regarding who the process owner was, whether OCHRO or OCG. Regardless, while being members of the SPAC, OCHRO and OCG rarely attended meetings.

Leading practice would see external service providers (that is, firms) included as observers/members in governance bodies. According to documentation received, an External Advisory Committee was struck to provide strategic advice and guidance to the Minister and Pay Modernization project executives. It met 8 times and included 2 to 3 external members representing private sector companies. This committee received project updates at their meetings and provided advice to the project team.

The Change Agent Network was the product of combining the Empowering Change Network (established for the Pay Modernization project) and the Change Agent Network (established for the Pay Consolidation project). The purpose was to share information with departments/agencies, which could then be used to brief up and throughout the organization. It was composed of representatives of all departments and agencies affected by Pay Modernization. While organizations were encouraged to appoint individuals at a manager level or above, this was not the case for many organizations. In fact, some organizations appointed people at a much more junior (for example, AS-02) level. Additionally, attendance by many departments and agencies was uneven with some organizations hardly attending at all and other attending frequently. Generally, attendance by departments and agencies was good until October 2015 when attendance dropped to less than 50%. However, the change agents consulted as part of the study (at all levels) felt that they did not completely understand their role (as the primary point of contact between PSPC and their organization) and that information provided at meetings was not clear or adequate to allow organizations to fully understand the status of the projects or their role, particularly pertaining to change management.

The TPAUMC was established in early 2011 based on a request from the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC) for meaningful consultation on the TPA with a view to minimizing the adverse effects on employees. The committee met at least quarterly from 2011 to the end of 2015. While no one consulted from PSPC or TBS mentioned this committee during the consultations for this study, PSAC spoke about the committee at length. While the union felt the committee was a very useful forum for discussing the workforce adjustment impact of the TPA on existing compensation advisors, the union did not feel the Government of Canada representatives were responsive to the concerns raised by the union at the committee about the rollout of TPA. According to PSAC, PSPC did not share key documents with the committee that would have likely led to red flags early on in the process. Additionally, according to PSAC, PSPC never wavered from its plan that the Pay Centre could be run by 550 employees, despite numerous concerns raised by the union at meetings of the committee.

While not a formal part of TPA governance, over the timeframe of the initiative, the project executives presented to PSMAC 7 times. According to many of those consulted for the study, PSMAC was often used as a senior governance body for the initiative. That is, PSMAC was asked to determine departmental readiness for go-live and to provide advice about key project milestones. However, members of PSMAC, having only received a limited number of briefings and not being completely attuned to the various initiative (and project) nuances, were not well-placed to provide this kind of advice. It is the opinion of the study team that the use of existing enterprise-wide advisory or information sharing bodies (such as PSMAC) should not be regarded as a substitute for governance of such significant transformation initiatives.

Oversight: Ensure oversight provides sufficient challenge

Oversight is a critical function in any transformation initiative, group of projects or project. It is carried out on behalf of the accountable leader in order to monitor risks, issues, schedule, budget, scope and outcome achievement. It is a challenge role, having a degree of independence from the ongoing management of the initiative or project itself.

Lesson 5

Establish a challenge function for effective independent oversight that encompasses the complete scope of the transformation, drawing upon organizations with international experience and individuals in that transformation area, and reporting directly to the minister or deputy head accountable for the overall initiative.

As mentioned, TBS CIOB ITPROD has a mandate for the oversight of complex IT projects within the Government of Canada. One important way that ITPROD carries out its oversight role is through attendance as an ex officio member at project governance meetings. Membership at assistant deputy minister (ADM)-level SPACs is the ADM of CIOB, the Executive Director of ITPROD, or the assigned Oversight Executive, depending on the project. At the SPAC for TPA, the Government of Canada Chief Information Officer (that is, the ADM of CIOB) was ITPROD’s representative at the committee. However, the study team heard that ITPROD’s influence was arguably weak during the timeframe of the initiative due to cutbacks as a result of the Deficit Reduction Action Plan and the tendency to delegate attendance at SPAC meetings (according to meeting minutes, the ADM CIOB attended less than 25% of meetings). A review of the minutes from the SPAC meetings further revealed that delegated representatives rarely voiced concerns or questions whereas the ADM CIOB, when in attendance, would frequently make contributions to the meeting that resulted in action items. The study team heard that while senior managers at ITPROD did voice concerns about the dashboards, these concerns were not reflected in updated dashboards and PSPC project management leadership team took steps to reassure ITPROD and CIOB at TBS that the project was on track (for example, through phone calls).Footnote 46 Further exacerbating the challenges pertaining to the role of ITPROD, their role was limited to oversight of the Pay Modernization project only.

Thus, the initiative was operating within an environment of limited oversight other than the management hierarchy at PSPC. Since this oversight was within the organization, there was limited independence of those tasked with the challenge role. Within that hierarchy, the study team heard from those consulted from both within and outside PSPC that there was a culture (at PSPC in particular, but also to some extent within the Government of Canada more broadly) that is not open to risk and does not reward speaking truth to power. Additionally, we heard that this culture of discouraging briefings with bad news was particularly strong at PSPC during the timeframe of the initiative. According to many of those consulted for the study, project briefings provided a more positive report on project progress and minimized areas of concern raised by others within PSPC (including individuals from the Chief Information Officer Branch and Finance and Administration Branch of PSPC). Those who observed the practice could not say definitively whether project management executives were unaware of the problems, unwilling to admit there were problems or were rather hoping that they would be able to address the problems in a timely manner/before the next briefing.

This practice of not providing briefings that contained bad news was exacerbated by a tendency to accord a great deal of leeway to managers with a good track record of managing projects. In particular, the study team heard from multiple sources that if certain managers were assuring others that problems would be resolved or that the project was on track, senior managers/decision-makers were more likely to believe those managers rather than to seek independent confirmation of what they were being told about problems.

Given that TPA was managed in a cultural environment that did not reward those who spoke truth to power (that is, to identify and communicate problems) and a tendency to believe those with good reputations, a strong oversight/challenge function was needed. Senior management, decision-makers and those asked to provide input should have been willing to ask for an independent assessment of what was in the briefings. For example, independently validated assessment for government-wide readiness to proceed with the go-live launch (from both PSPC as well as departments and agencies) should have been sought by PSMAC when this body was asked to provide advice on readiness to launch.

Other stakeholders within the government system should have also played a stronger challenge role. For example, TBS in its role pertaining to ensuring the quality of Treasury Board Submissions and adequate follow-up and reporting to Treasury Board could have required more frequent and formal reports to Treasury Board regarding project progress, coupled with evidence of progress. Also, others with responsibilities pertaining to compensation (including OCHRO and OCG) could have stepped forward and asked more questions. Members of the various governance/advisory bodies who received briefings could have asked more pointed questions and, upon not receiving a satisfactory response, could have escalated their concerns to their deputy head. Internal audit units could have conducted audits of departmental readiness for the transition to Phoenix and/or could have escalated any concerns they may have had to the Office of the Comptroller General. Those within OCHRO could have better advocated for the compensation advisor community regarding the complexity of their role and concerns about the ability of the Government of Canada to operate effectively after go-live. The design of the Pay Consolidation project combined with the decision to locate the Pay Centre in Miramichi effectively meant that the pre-existing knowledge and capacity of the compensation advisor members was eliminated. It is important to note that compensation advisors were represented by their union, PSAC, which spurred the development of the TPAUMC. However, the work of that committee does not appear to have influenced the outcome of the TPA in any meaningful way. Decisions were made despite the warnings issued by the union representatives at TPAUMC.

It is the view of the study team (based on leading practices) that third parties who have extensive comparable experience globally should be brought in as a regular part of the challenge function to provide independent assessments of progress of the initiative as a whole and to share leading practices from other jurisdictions.Footnote 47 The scope of these independent assessments should be sufficiently broad and report directly to the senior governance body. While 3 independent reviews (linked with 3 of the Gates, per guidelines for project management oversight) were conducted for the Pay Modernization project, these reviews unfortunately were very limited in scope, and although following Treasury Board policy direction for IT project oversight, were not effective. A closer examination of this work reveals that those consulted for the reviews were limited to project management personnel within PSPC and that the reviews were very IT-focused. Thus, although appearing to be effective reviews, they did not identify significant problems or issues with the project, or the broader TPA Initiative and each review recommended proceeding to the next phase of the project.

3.3 Change management

Culture/leadership environment: Assess and then adapt or manage the culture and leadership environment

Organizational culture is defined as the shared values of and behaviors uniquely common to an organization. Organizational culture is integral in determining how tasks are completed, the way people interact with one another, the language they use when communicating, and the attitudes, goals, values, and leadership behaviors that are exhibited.

As they embark on a large transformation, leaders need to assess the organizational culture to determine the cultural elements within the organization that may help or hinder the change direction and achievement of expected benefits.

This assessment determines if the organization’s current culture, structure, processes, and performance management system will support the change. If so, then the assessment process will investigate how the current culture can be managed through the change. If the current culture will not support the change, then the assessment identifies the aspects of the current culture requiring change in order to realize the future state.

Indicators that a cultural change may be necessary to support and sustain the change include:

- the current culture does not allow stakeholders to work in ways that support the future state

- the current culture does not support the planned organizational process or behavior change

- the current values are in conflict with what will be expected of the stakeholders and leadersFootnote 48

Lesson 6

Assess the culture of the organization(s) in which the transformation is occurring. Ideally, organizational culture should be agile, open to change, engaging, responsive to stakeholder feedback and willing to receive unwelcome and unexpected information. Where culture is not ideal, take steps manage the transformation within that culture (e.g., heightened challenge function, effective communications).

The public service culture and environment at the time of the change initiative was described as being unreceptive to inconvenient feedback. The study team heard that this unreceptive culture was further compounded by the existing top-down approach to management within TPA. We heard this tendency to ‘bury bad news’ and to only brief up the good news was 1 of the reasons some of the major concerns were not raised, were not considered, or did not reach senior levels.