Evidence synthesis – COVID-19 among Black people in Canada: a scoping review

HPCDP Journal Home

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: March 2024

ISSN: 2368-738X

Submit a manuscript

About HPCDP

Browse

Previous | Table of Contents | Next

Adedoyin Olanlesi-Aliu, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1; Janet Kemei, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1; Dominic Alaazi, PhDAuthor reference footnote 2; Modupe Tunde-Byass, FRCSAuthor reference footnote 3Author reference footnote 4; Andre Renzaho, PhDAuthor reference footnote 5; Ato Sekyi-Out, PhDAuthor reference footnote 6; Delores V. Mullings, PhDAuthor reference footnote 7; Kannin Osei-Tutu, CCFPAuthor reference footnote 8; Bukola Salami, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1Author reference footnote 2Author reference footnote 9

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.44.3.05

This article has been peer reviewed.

Recommended Attribution

Research article by Olanlesi-Aliu A et al. in the HPCDP Journal is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Author references

Correspondence

Adedoyin Olanlesi-Aliu, Faculty of Nursing, 4-171 Edmonton Clinic Health Academy, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T6G 1C9; Tel: 825-993-9814; Email: olanlesi@ualberta.ca

Suggested citation

Olanlesi-Aliu A, Kemei J, Alaazi D, Tunde-Byass M, Renzaho A, Sekyi-Out A, Mullings DV, Osei-Tutu K, Salami B. COVID-19 among Black people in Canada: a scoping review. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2024;44(3):112-25. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.44.3.05

Abstract

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated health inequities worldwide. Research conducted in Canada shows that Black populations were disproportionately exposed to COVID-19 and more likely than other ethnoracial groups to be infected and hospitalized. This scoping review sought to map out the nature and extent of current research on COVID-19 among Black people in Canada.

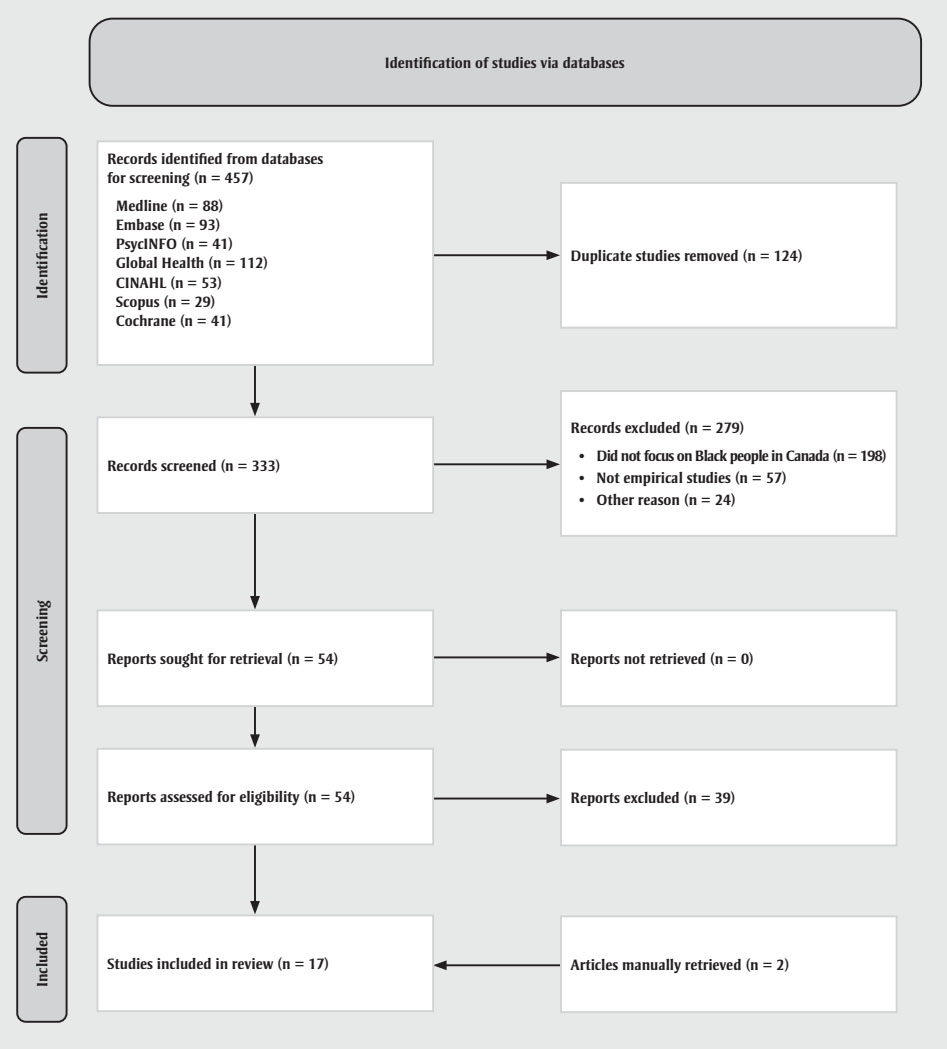

Methods: Following a five-stage methodological framework for conducting scoping reviews, studies exploring the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Black people in Canada, published up to May 2023, were retrieved through a systematic search of seven databases. Of 457 identified records, 124 duplicates and 279 additional records were excluded after title and abstract screening. Of the remaining 54 articles, 39 were excluded after full-text screening; 2 articles were manually picked from the reference lists of the included articles. In total, 17 articles were included in this review.

Results: Our review found higher rates of COVID-19 infections and lower rates of COVID-19 screening and vaccine uptake among Black Canadians due to pre-COVID-19 experiences of institutional and structural racism, health inequities and a mistrust of health care professionals that further impeded access to health care. Misinformation about COVID-19 exacerbated mental health issues among Black Canadians.

Conclusion: Our findings suggest the need to address social inequities experienced by Black Canadians, particularly those related to unequal access to employment and health care. Collecting race-based data on COVID-19 could inform policy formulation to address racial discrimination in access to health care, quality housing and employment, resolve inequities and improve the health and well-being of Black people in Canada.

Keywords: racialized populations, inequity, vaccine hesitancy, racial discrimination

Highlights

- Black Canadians are overrepresented in frontline jobs, which increases their risk of contracting COVID-19.

- Low uptake of COVID-19 screening and vaccine hesitancy may be attributed to mistrust of the health care system in Canada.

- Existing structural racism within the Canadian health care system has created inequities in accessing COVID-19–related health care services among Black Canadians.

- There is a need to collect race-based data with a focus on resolving inequities and improving the health and well-being of Black people in Canada.

Introduction

The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic in March 2020, triggering the adoption of numerous public health measures, including lockdowns, social distancing and the use of facemasks in public places. However, the health risks of COVID-19 infection and public health measures to reduce infection did not affect everyone equally;Footnote 1Footnote 2Footnote 3Footnote 4Footnote 5 the burden was disproportionately greater for racialized people and those living in low-income communities.Footnote 6

Black people in Canada, the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (USA) experienced a disproportionately higher prevalence of COVID-19 infections and a greater risk of COVID-19-related hospitalizations and mortality compared to their White counterparts.Footnote 7Footnote 8Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11Footnote 12Footnote 13 For every 100 000 Americans, about 26 Black people died from COVID-19 infection, a mortality rate more than twice that of Latino, Asian or White people.Footnote 13 In the UK, the mortality rate among Black people was likely four times that of their White counterparts.Footnote 14Footnote 15Footnote 16Footnote 17 Despite representing only 9.28% of the population of Toronto, Ontario, Canada’s largest city, Black people accounted for nearly one-quarter of COVID-19 cases in 2020, while White people, who constituted 49.64% of the city’s population, represented only 21.7% of cases.Footnote 18

Canada is a common destination for international migrants, with a growing population of Black people from sub-Saharan African and Caribbean nations.Footnote 19 Black people are the third-largest racialized group in Canada, at 4.3% of the country’s total population, after South Asian (7.1%) and Chinese (4.7%) people.Footnote 20

Most of the reasons why the Black population was highly susceptible to and affected by COVID-19 infection are rooted in social determinants of health, such as socioeconomic status, crowded living environments, cultural barriers, racial discrimination, poor access to health care and anti-Black racism.Footnote 21 In Canada and the USA, systemic racism cuts across all sectors—health care, education and the labour force—a problem that continues to be overlooked in policies.Footnote 21Footnote 22 Because of the extensive emphasis on individual behaviours, rather than tackling the challenges that confront systemically marginalized Black people,Footnote 21 the health care system failed to account for numerous inequities, including in education and employment, that tended to expose Black people to high rates of COVID-19 infection and mortality, to the point that racism has been described as “a risk factor for dying from COVID-19.”Footnote 23

For instance, racialized and immigrant populations experienced unequal access to vaccination and high rates of infection and death from COVID-19.Footnote 24Footnote 25 A significant proportion of Black people are precariously employed and overrepresented in risky but essential frontline jobs across Canada, as well as in the UK and the USA,Footnote 17Footnote 26 where the risks of COVID-19 infection were high.Footnote 27Footnote 28Footnote 29Footnote 30 Racial inequalities to do with health and environmental factors affect racialized people in a way that left them “more exposed [to] and less protected” from the COVID-19 virus.Footnote 8Footnote 23Footnote 30

Data from the USA demonstrate racial disparities in rates of COVID-19 infection and mortality, with Black people among the most disadvantaged.Footnote 8Footnote 23 However, few studies have focussed on COVID-19 among Black Canadians. Given the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 and the distinct risks that Black Canadians face, the purpose of this scoping review was to map out the scope of research on COVID-19 among Black people in Canada.

Methodology

We utilized a scoping review methodology to explore the “extent, range and nature of research activity,”Footnote 31 explicate what is currently known about COVID-19 among Black Canadians and pinpoint knowledge gaps for future research. We applied Arksey and O’Malley’sFootnote 31 five-stage methodological framework for conducting scoping reviews: identifying the research question; identifying relevant studies; selecting studies; charting the data; and collating, summarizing and reporting the results. We used the Tricco et al.Footnote 32 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) approach.

Identifying the research question

This review was guided by the following question: “What is the scope and nature of the literature on COVID-19 among Black people in Canada?”

Identifying relevant studies

We identified relevant studies through a systematic search in seven electronic databases: Ovid MEDLINE (Table 1), Elsevier Embase, APA PsycINFO, CABI Global Health, EBSCO CINAHL, Elsevier Scopus and the Wiley Cochrane Library. Our search strategy was derived based on two main concepts: (1) COVID-19 (all variants), and (2) Black people in Canada.

| Ovid Medline | |

|---|---|

| Concept | Query |

| 1 | (((exp Coronavirus/ or exp Coronavirus Infections/ or (coronavirus* or corona virus* or OC43 or NL63 or 229E or HKU1 or HCoV* or ncov* or covid* or sars-cov* or sarscov* or Sars-coronavirus* or Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus*).mp.) and 20190601:20301231.(ep).) not (SARS or SARS-CoV or MERS or MERS-CoV or Middle East respiratory syndrome or camel* or dromedar* or equine or coronary or coronal or covidence* or covidien or influenza virus or HIV or bovine or calves or TGEV or feline or porcine or BCoV or PED or PEDV or PDCoV or FIPV or FCoV or SADS-CoV or canine or CCov or zoonotic or avian influenza or H1N1 or H5N1 or H5N6 or IBV or murine corona*).mp.) or Covid-19/ or (covid or covid19 or 2019-ncov or ncov19 or ncov-19 or 2019-novel CoV or sars-cov2 or sars-cov-2 or sarscov2 or sarscov-2 or Sars-coronavirus2 or Sars-coronavirus-2 or SARS-like coronavirus* or coronavirus-19 or ((novel or new or nouveau) adj2 (CoV or nCoV or covid or coronavirus* or corona virus or Pandemi*2)) or (variant* adj2 (India* or "South Africa*" or UK or English or Brazil* or alpha or beta or delta or gamma or kappa or lambda or "P.1" or "C.37")) or ("B.1.1.7" or "B.1.351" or "B.1.617.1" or "B.1.617.2")).mp |

| 2 | exp African Continental Ancestry Group/ |

| 3 | (black* or african* or caribbean or afro* or "person of colo?r" or "people of colo?r" or colo?red or "dark-skin*" or BIPOC or ((racial or ethnic) adj2 minorit*)).mp |

| 4 | 2 or 3 |

| 5 | exp Canada/ or (Canad* OR "British Columbia" OR "Colombie Britannique" OR Alberta* OR Saskatchewan OR Manitoba* OR Ontario OR Quebec OR "Nouveau Brunswick" OR "New Brunswick" OR "Nova Scotia" OR "Nouvelle Ecosse" OR "Prince Edward Island" OR Newfoundland OR Labrador OR Nunavut OR NWT OR "Northwest Territories" OR Yukon OR Nunavik OR Inuvialuit) |

| 6 | 1 and 4 and 5 |

Selecting studies

Our initial search was conducted in January 2022 with no time restrictions. We subsequently updated the search to include all records published to 31 May 2023. A total of 457 records underwent initial screening of titles and abstracts (by AO and JK), and 124 duplicates were excluded. Two authors (AO and JK), working independently, reviewed the abstracts of the remaining 333 articles. Any conflicts during the process of selecting articles were resolved by a third author (DA). An additional 279 articles were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria (studies focussing on Black people living in Canada and on COVID-19). Of the remaining 54 articles, 39 were excluded after the full-text screening. In total, 17 articles were included in this review.

The selection process is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1 - Text description

This figure depicts the flow diagram of the identification and selection of studies via databases for the scoping review.

In the identification stage, n = 457 records were identified from databases for screening, as follows:

- Medline (n = 88)

- Embase (n = 93)

- PsycINFO (n = 41)

- Global Health (n = 112)

- CINAHL (n = 53)

- Scopus (n = 29)

- Cochrane (n = 41)

Duplicate studies (n = 124) were removed, leaving n = 333 records to be screened in the screening step. Of these, n = 279 records were excluded, for the following reasons:

- Did not focus on Black people in Canada (n = 198)

- Not empirical studies (n = 57)

- Other reason (n = 24)

As a result, n = 54 reports were sought for retrieval, of which n = 0 reports were not retrieved. These 54 reports were assessed for eligibility, resulting in n = 39 reports to be excluded.

In the final step, n = 17 studies were included in the review, including n = 2 articles manually retrieved.

Adapted from: Page et al.,Footnote 33 Tricco et al.Footnote 32

Charting the data

Two research team members (AO and JK) conducted the data extraction, which involved charting and sorting the findings of the included studies into key issues and analytical categories related to the impact of COVID-19 on Black people in Canada. The following information was extracted from each of the included articles and recorded on an Excel spreadsheet (version 2007; Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, US) designed by the research team: author name(s), year of publication, study purpose/research question, study population, methods, results/findings and comments/implications (Table 2). A research team member (DA) performed a quality check to ensure completeness and accuracy.

| Author(s) | Study purpose / research question | Study population | Methods | Results/findings | Comments/implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed et al. (2021)Footnote 35 | To examine the needs and concerns of Black communities in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) and to show the importance of collecting race-based COVID-19 data | Local community health centre leaders | Qualitative interviews (n = 6) | The community leaders indicated that Black Canadians were unwilling to screen for COVID-19 due to misconceptions (e.g. the test is painful, getting infected with COVID-19 from screening). Mobile testing was provided for nonracialized GTA neighbourhoods before areas with worse living conditions and worse access to health care. The community leaders highlighted discrepancies in resource allocation among specific populations that indicates systemic discrimination and neglect. The community leaders recommended early measures to prevent COVID-19 cases among Black people and other people of colour. | The findings suggest that greater numbers of Black Canadians and racialized people are affected by COVID-19 because of inequity among frontline workers and people living in low-income communities, indicating the necessity of collecting race-based COVID-19 data. |

| Cénat et al. (2023)Footnote 44 | To examine the sociodemographic characteristics and factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine mistrust in the Black population in Canada | Black individuals in Canada | Quantitative (n = 2002) | Participants with previous COVID-19 infection had greater COVID-19 vaccine mistrust scores (M = 11.92, SD = 3.88) than those with no previous COVID-19 infection (M = 11.25, SD = 3.83), t (1999) = −3.85, p < 0.001. Participants who experienced major racial discrimination in health care settings were more likely to report COVID-19 vaccine mistrust (M = 11.92, SD = 4.03) than those who had not (M = 11.36, SD = 3.77), t (1999) = −3.05, p = 0.002. The mediated moderation model revealed that conspiracy theories totally mediated the association between racial discrimination and vaccine mistrust (B = 1.71, p < 0.001). | It is essential to create health educative programs that can emphasize health literacy among the Black population in Canada. |

| Choi et al. (2021)Footnote 39 | To identify the key demographic factors for COVID-19 infections across Canada’s health regions | People living in Canada | Quantitative (secondary data) | COVID-19 infections are more prevalent in health regions with greater numbers of Black and low-income residents. Population density and urban centres are significantly correlated with COVID-19 infections. The number of Black residents in a neighbourhood determines the number of COVID-19 infections. | Collection of race-based data and better policies that target racial discrimination, unequal access to health care and crowded and inadequate housing are needed. |

| Etowa et al. (2023)Footnote 45 | To examine factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine willingness using logistic regression analysis | African, Caribbean and Black (ACB) people | Quantitative (n = 375) | ACB persons who opined that the ACB group is at a higher risk for COVID-19 were more likely to be willing to get vaccinated than those who did not (OR = 1.79, p < 0.05). ACB individuals who had received a minimum of 1 dose of the COVID-19 vaccine were more likely to be enthusiastic to receive it in the future (OR = 2.75, p < 0.05). In addition, ACB persons with a postgraduate degree (OR = 2.21, p < 0.05) were more likely to report vaccine willingness compared to those without a bachelor’s degree. | It is necessary to address limited COVID-19 risk perception and knowledge among ACB, non-existence of prior COVID-19 vaccine experience, and mistrust of government COVID-19 information. To resolve these issues, it may be useful to incorporate culturally and linguistically sensitive messaging and outreach about COVID-19 and vaccines. |

| Etowa et al. (2021)Footnote 48 | To assess current knowledge gaps in COVID-19 care for African, Caribbean and Black (ACB) communities | ACB community | Qualitative | There is a lack of information on how socioeconomic vulnerability, comorbidity and discrimination influenced health care access and outcomes in ACB communities. There is insufficient information on the type of training frontline health workers and administrators require with respect to services for ACB communities. No concrete evidence is available to enhance strategies to ensure health equity and mitigate the impact of COVID-19 in ACB communities. | Research participation among the stakeholders (community leader, health providers) should be promoted to generate approaches to tackle COVID-19-related health outcomes. |

| Gerretsen et al. (2021)Footnote 42 | To assess variations in vaccine hesitancy, complacency and confidence among extremely affected ethnic groups in Canada and the USA | Indigenous (Native American, American Indian, First Nations, Inuit and Métis), Black, Latinx (Hispanic), East Asian (Chinese, Japanese or Korean) and White racial/ethnic groups | Quantitative: web-based survey | Compared to White participants, Black and Indigenous survey participants in Canada and the USA have greater vaccine hesitancy and mistrust in vaccine efficacy with concerns about potential future side effects, commercial gain and favouring Whites despite that these populations perceive COVID-19 with the same level of seriousness. Racial minorities with less education and employment, lower incomes and higher levels of conservatism or religiousness than White participants were also more likely to be affected by COVID-19. | Local and national governments can achieve herd immunity against COVID-19 across racialized communities by ensuring vaccine accessibility and targeted cultural and community-sensitive efforts to raise vaccine confidence. |

| Innovative Research Group (2021)Footnote 43 | To identify factors that influence COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and the communities that are more hesitant | Black Canadians | Quantitative online survey | Black Canadians reported lower vaccination rates due to their low confidence in vaccines. Some likely contributing factors to low vaccine confidence and high vaccine hesitancy within the Black community include distrust of health care providers and vaccine manufacturers and concerns related to vaccine risks. A vital aspect related to low vaccine uptake was lack of paid sick leave or paid vaccination leave. | The study urges Canadian federal and provincial governments to provide strategies geared towards partnerships with Black-led and Black-focussed community groups to appropriately manage COVID-19 vaccine knowledge gaps and factors related to distrust and blockades through culturally sensitive and safe implementation of government-supported education that takes into account language and education differences as well as socioeconomic disparities. |

| Kemei et al. (2023)Footnote 38 | To describe the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on Black Canadians | Black stakeholders in Canada | Qualitative | In the early part of COVID-19 pandemic, the propagation of COVID-19 disinformation in Black communities exacerbated Black Canadians’ vulnerability to COVID-19 as a result of increased vaccine hesitancy. | The participants recommended tackling systemic inequities in health care; promoting cultural competency among service providers; increasing diversity in health care, in particular by employing larger numbers of Black health care personnel; and promoting Afrocentric approaches to health care. |

| Kemei et al. (2023)Footnote 40 | To explain the nature of online COVID-19 disinformation among Black people in Canada and identify the factors contributing to this phenomenon | Black stakeholders in Canada | Qualitative | Underlying systemic racism and related inequities in Canada has built mistrust in public health personnel and resulted in Black Canadians’ readiness to replace truths about COVID-19 with disinformation. | There is a need to build trust and accept collaborative strategies in resolving community worries such as employment discrimination, medical racism and anti-racist workplace practices and policies, and provide funds to existing Black community organizations to create culturally congruent health education material. |

| Lei & Guo (2022)Footnote 46 | To understand social issues of inequality with focus on exposing unequal power relations and hegemonic knowledge | Asian, Black and Indigenous ethnic groups in Canada | Quantitative | The increase of anti-Black racism since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic indicates that multiculturalism has, in effect, sustained a racist and unequal population in Canada, with racism embedded in its history and built into every aspect of its social structure and socioeconomic and health care services, resulting in inequities. Multiculturalism allows cultural variance but does not dispute an unjust society premised on white sovereignty. The significant link between police cruelty towards Black people in Canada, increased rates of Covid-19 in the Black population and the correlation of their low socioeconomic status, low level of education, and lower-paying employment with great risk of exposure to Covid-19, serve as a symbol of historical racism against Black people. | A pandemic anti-racism education model is sourced from critical race theory and seeks to address and eradicate all pandemic-related racism, xenophobia and racial oppression beyond COVID-19 within Canada. |

| Miconi et al. (2020)Footnote 47 | To examine the association of exposure to the COVID-19 virus to discrimination and stigma associated with mental health among culturally diverse adults in Quebec | White, Asian (East, South and South-East), Black, Arab, Other (first, second, third or more immigrant generations) | Quantitative | Exposure to COVID-19 predominately affected Black, Arab and South Asian participants. Asian and Black participants disclosed greater COVID-19-related discrimination and stigma. Increase in negative mental health outcomes was associated with exposure and or COVID-19-related discrimination. Among minority groups, Black respondents described the worst mental distress due to pandemic risk factors. | Policies and discourse should focus on promoting societal partnerships, decreasing discrimination against racialized communities and ensuring security of vulnerable groups. Community-based antidiscrimination programs should be established. Accessible and culturally sensitive mental health services are required for racial minorities during and beyond the pandemic. |

| Noble et al., (2022)Footnote 49 | To describe the impacts of the pandemic on youth experiencing homelessness in Toronto, Ontario | Youth experiencing homelessness | Mixed method | Systemic racism (exemplified by the successive public displays of police cruelty against unarmed Black citizens) and the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated distress among the Black youth experiencing homelessness. They found it very difficult to secure employment and were discriminated against by landlords, which make it difficult for them to get accommodation. | There is a need to stabilize health and continuous access to in-person services that centre on provision of housing and equitable supports for subcategories of youth. |

| Pang et al. (2021)Footnote 50 | To determine mental health risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic among eye care professionals | Eye care professionals (doctors, staff and students) in the USA and Canada | Quantitative | Female, younger, and Black or Asian eye care professionals and students were more prone to mental distress on all assessed factors. Racial inequity and racism seemingly contribute to these results, especially considering that Black people experience higher rates of COVID-19 exposure and severity of illness, which might add to greater mental health challenges for Black eye care professionals. | The findings suggest the need to develop strategies that target young and female students and racial minorities to improve their mental health. |

| Pongou et al. (2022)Footnote 36 | To examine the association between reported COVID-19 symptoms and testing for COVID-19 in Canada | N = 2790 White: n = 2402 Black: n = 85 Mixed race/ethnicity: n = 126 Other ethnoracial groups: n = 177 |

Quantitative | Prevalence of testing for COVID-19 differed by ethnicity (White: 17.30%; Black: 8.46%; mixed race/ethnicity: 28.41%; other ethnic groups: 27.37%). | There is a need to accelerate COVID-19 testing in Canada, and for the provinces of British Columbia and Quebec in particular to accommodate the need for COVID-19 tests and expand accessibility and availability of testing. |

| Pongou et al. (2022)Footnote 51 | To examine the predictors of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada and how they differ by gender. | N = 2756 White: n = 2364 Black: n = 83 Mixed race/ethnicity: n = 177 Other race/ethnicity: n = 132 |

Quantitative | Descriptive analysis indicates that nearly half of the participants (49%) experienced mild, moderate or severe psychological distress. Mild: White: 26.15, Black: 34.97, mixed race/ethnicity: 32.25, other ethnic group: 25.33. Severe: White: 7.70, Black: 3.06, mixed race/ethnicity: 4.25, other ethnic group: 16.96 p < 0.069 The odds of psychological distress were significantly higher for participants who declared COVID-19 symptoms compared to those who did not declare COVID-19 symptoms. |

There is a significant need to make mental health support services available to vulnerable groups. Also, interventions and policies targeted at tackling psychological distress throughout pandemics such as COVID-19 should be gender specific. |

| Richard et al. (2022)Footnote 41 | To describe COVID-19 vaccine coverage in the homeless population in Toronto and explore factors related to the receipt of at least 1 dose. | N = 728 Indigenous: n = 27 White: n = 353 Black: n = 159 Other/multiracial: n = 156 |

Quantitative | Slightly more than 80.4% of participants received at least 1 COVID-19 vaccine; 63.6% received ≥2 doses. Black participants were consistently found to have lower vaccination acceptance or greater hesitancy. Black (18.3% vaccinated vs. 32.9% unvaccinated] [Arr0.89 [95% CI: 0.80–0.99]) | More public health approaches are required to understand and resolve how interconnecting experiences of marginalization and oppression encountered by various of the subgroups recognized in this study influence the choices and opportunities to uptake vaccination. |

| Rocha et al. (2020)Footnote 37 | To highlight the dire need to collect race-based data on increased morbidity, mortality and exposure to COVID-19 in subpopulations in Montréal, Quebec, by socioeconomic factor with a particular focus on Black populations. | Montréal’s demographic groups, including the Black population, neighbourhoods, income, education, essential workers and crowded housing. | Quantitative | There is an association between COVID-19 cases and socioeconomic factors such as race and housing: of all marginalized groups, the strongest association with positive COVID-19 cases occurred in Montréal boroughs with high proportions of Black residents: Montréal-Nord, with a high proportion of Haitian people, and Rivière des Prairies, Pointe aux Trembles, LaSalle, Villeray and Parc-Extension. Strong correlations also existed between COVID-19 cases and health care workers, low-income earners and those living in inadequate and crowded housing. Another key correlation for COVID-19 exposure also occurred among under-educated persons in Montréal. | The Canadian government needs to collect race-based data as these are critical for highlighting and understanding key socioeconomic influences and the shared experiences of Black people, especially in relation to the effect of COVID-19 on Black populations in Montréal. |

Collating, summarizing and reporting the results

We analyzed quantitative data from numerical summary and qualitative studies using thematic analysis. Drawing on Braun and Clarke,Footnote 34 two research team members (AO and JK) read the included articles several times, familiarized themselves with the data, and synthesized and categorized the interpretations of recurring findings into themes. They then open coded the extracted data by going through the fragments of texts, line by line, and assigning labels that best described these fragments. The codes were then compiled into potential themes, all the data relevant to each potential theme were grouped together, and the data were compared across the coded excerpts and the entire dataset. Two other research team members (DA and BS) reviewed the assigned codes and themes.

Ethics approval

This scoping review does not contain any studies with human participants or animals that may have required ethics approval.

Results

A total of 17 empirical studies met our inclusion criteria. Twelve articles used quantitative methodologies (mostly cross-sectional study designs), four used qualitative methodologies (mostly explorative) and one used mixed methods. All included articles described the impacts on Black Canadians of, for example, poor accessibility to COVID-19–related health care services, health inequities caused by COVID-19 and the role of systemic discrimination and racism in the creation of these inequities.

Our findings are presented in five themes: low uptake of COVID-19 screening; high rates of COVID-19 infection; low uptake of COVID-19 vaccines; systemic racism and discrimination; and mental health impacts.

Low uptake of COVID-19 screening

Two studies reported on disparities in COVID-19 screening.Footnote 35Footnote 36 In a cross-sectional study, Pongou et al.Footnote 36 found that the prevalence of being tested for COVID-19 across reported COVID-19 symptoms was far lower among Black Canadians (8.46%) than among those who were White (17.30%), mixed race/ethnicity (28.41%) or from another ethnoracial group (27.37%), although the differences were not statistically significant.

In a 2021 qualitative study, local community health centre leaders who serve communities with large populations of racialized people within the Greater Toronto Area expressed concerns that individuals’ reluctance to get tested for COVID-19 were due to misconceptions that the test is painful and that people can get infected with COVID-19 from screening.Footnote 35 The study also noted discrepancies in resource allocation within the health care system. For instance, mobile testing was made available in nonracialized neighbourhoods sooner than in poorer and racialized areas with worse access to health care.Footnote 35

High rates of COVID-19 infection among Black Canadians

Four studies examined high rates of COVID-19 infection among Black Canadians.Footnote 36Footnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39 A quantitative study indicated that higher numbers of COVID-19 cases are associated with socioeconomic factors such as race and housing. For instance, of all marginalized groups in Montréal, Quebec, the strongest relationship with positive COVID-19 cases occurred among those living in overcrowded housing and in boroughs with high proportions of Black people.Footnote 37

Two qualitative studies reported on the greater risks for Black people of contracting COVID-19 as a result of overrepresentation in frontline work and low-income communities.Footnote 37Footnote 38 Using COVID-19 counts and tabular census data, Choi et al.Footnote 39 showed that there were relatively higher numbers of infections in communities with larger proportions of Black and low‐income residents across Canada. These vulnerabilities were created by poverty, overcrowded living environments, predominance of frontline work and existing health care inequities.Footnote 36Footnote 37

Low uptake of COVID-19 vaccines

Seven studies explored low uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among Black Canadians.Footnote 38Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42Footnote 43Footnote 44Footnote 45 A quantitative study exploring COVID-19 vaccine coverage among people experiencing homelessness in Toronto found that about 80.4% of participants received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and 63% had received two or more doses; however, Black participants were consistently found to have greater vaccine hesitancy, likely because of distrust in health care providers, perceived commercial gains for vaccine manufacturers, perception of vaccine risks, and lack of paid sick or vaccination leave.Footnote 41

Two qualitative studies reported that the spread of disinformation and misinformation about COVID-19 within Black communities in Canada during the early part of the pandemic affected people’s understanding of the risk of the consequences of COVID-19 infection, which propagated vaccine hesitancy.Footnote 38Footnote 40 Gerretsen et al.Footnote 42 conducted a quantitative web-based survey in Canada and the USA to assess variations in vaccine hesitancy; the authors reported that despite perceiving COVID-19 with the same level of seriousness, Black and Indigenous people possess a greater degree of vaccine hesitancy and mistrust in efficacy than do White people due to concerns about potential future side effects and commercial gains and because they favoured natural immunity to a greater degree.

Two quantitative study findings reported lower vaccination rates and higher vaccine mistrust scores among Black individuals as a result of their experiences of major racial discrimination in the health care system.Footnote 43Footnote 44 In addition, a quantitative study of vaccine willingness found that African, Caribbean and Black individuals at greater risk of infection with COVID-19 were more willing to get vaccinated, and those who had received their first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine were more willing to receive upcoming doses.Footnote 45

Systemic racism and discrimination

The five studies that explored the difficulties Black Canadians faced during the pandemic as a result of systemic racism and discrimination determined that the difficulties study participants experienced accessing COVID-19-related health care might have been exacerbated by existing stress stemming from racism, systematic bias and barriers, and socioeconomic vulnerabilities.Footnote 40Footnote 46Footnote 47Footnote 48Footnote 49 The significant link between police cruelty towards Black people in Canada, increased rates of COVID-19 in the Black population and the correlation of lower socioeconomic status, lower level of education and lower-paying employment with great risk of exposure to COVID-19, serves as a symbol of the continuing and historical racism experienced by Black people.Footnote 46

The underlying systemic racism and related inequities resulted in mistrust of health care providers.Footnote 40 Miconi et al.Footnote 47 conducted a mixed study on risk of exposure to COVID-19 and the relation to discrimination and stigma associated with mental health findings. The authors reported that Black, Arab and South Asian participants had higher prevalence of infection, while Black and Asian participants disclosing greater COVID-19-related discrimination and stigma as a result of their employment, for example, as frontline workers.Footnote 47

The quantitative study conducted by Noble et al.Footnote 49 revealed that systemic racism and the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated mental distress among Black youth experiencing homelessness in Toronto, with barriers to securing employment and landlords’ racial discrimination making it difficult to obtain accommodation.

A qualitative study revealed that there was insufficient information on the type of training frontline health workers and administrators require when providing services to African, Caribbean and Black communities.Footnote 48 No concrete evidence is available to enhance strategies to ensure health equity and mitigate the impact of COVID-19 in African, Caribbean and Black communities.

Mental health impacts

Four studies reported on mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on Black people in Canada.Footnote 38Footnote 47Footnote 50Footnote 51 A qualitative study found that online misinformation about COVID-19 aggravated mental health issues among Black Canadians and resulted in fear of and anger about mandatory vaccine orders.Footnote 38 Some Black community members were afraid of being stigmatized whether they received or declined the COVID-19 vaccine, which amplified their anxiety about COVID-19 and prevented them from getting vaccinated or promoting vaccination.Footnote 38

In their quantitative study on eye care professionals’ mental health risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic, Pang et al.Footnote 50 reported poor emotional health among Black and Asian optometrists, noting that they were more prone to mental distress and elevated symptoms of depression and anxiety than other ethnoracial groups. Miconi et al.Footnote 47 reported an increase in negative mental health outcomes associated with exposure to the COVID-19 virus and/or COVID-19-related discrimination, with Black survey respondents describing the worst mental distress due to the pandemic. Further, research on predictors of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada show that nearly half of the participants (49%) experienced mild, moderate or severe psychological distress, with Black Canadians (mild: 34.97%; severe: 3.06%) reporting a higher percentage of mild and severe psychological distress compared to White (mild: 26.15%; severe: 7.70%) and mixed race/ethnicity (mild: 32.25%; severe: 4.25%) Canadians.Footnote 51

Discussion

This scoping review identified five themes addressing the impact of COVID-19 on Black Canadians. Key among our findings is evidence of the inequalities in access to COVID-19–related health care, which may be attributed to existing structural racism within the Canadian health care system. Given the highly infectious nature of the disease, inequalities in access to care in the context of COVID-19 affects the entire population. For instance, anyone who does not adopt COVID-19 preventive measures, prompt diagnosis and treatment, may contract the virus and spread it in their community.

The COVID-19 pandemic accentuated health inequities based on anti-Black racism. Two studies in this scoping review showed that early measures to control the spread of COVID-19 (e.g. screening) were not effectively implemented in the areas where most Black people resided, which increased residents’ risk of infection.Footnote 35Footnote 36 The COVID-19 mortality rate among Black people living in low-income areas was 3.5 times higher than in nonracialized and non-Indigenous populations living in low-income areas.Footnote 52 Further, Black people have been at greater risk of hospitalization for and dying from COVID-19 due to inadequate access to health care providers and services.Footnote 53Footnote 54 Other factors that contribute to the high rates of COVID-19 infection among Black people include poverty, poor and overcrowded living conditions, and employment in precarious frontline work.Footnote 55Footnote 56 Communities in Canada with larger proportions of Black and racialized populations had higher rates of COVID-19 infection and death.Footnote 55Footnote 56 For instance, Ontario is home to more than 50% of Canada’s Black population, and overrepresentation of COVID-19 cases were reported in Black neighbourhoods.Footnote 18Footnote 55Footnote 56Footnote 57 Other studies conducted in Edmonton, Alberta,Footnote 58 and Montréal, Quebec,Footnote 59 also revealed that Black Canadians were more likely to experience negative socioeconomic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 58Footnote 59 These results speak to the need for fair distribution of COVID-19 preventive and treatment services.

Several studiesFootnote 38Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42Footnote 44Footnote 45 in our scoping review described the low uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among Black Canadians. Vaccine hesitancy, recognized as a serious threat to public health, is significant among Black people. Some of the factors leading to vaccine hesitancy among Black Canadians are anti-Black racism in health care, distrust of the health care system and the failure to prioritize Black communities during vaccine rollouts.Footnote 40Footnote 42 This is consistent with the findings of a systematic review from CanadaFootnote 60 and a meta-analysis from the USA.Footnote 61 Statistics Canada reported that a much lower proportion of the Black population (56.4%) were very or somewhat willing to be vaccinated compared to White (77.7%) and South Asian (82.5%) populations.Footnote 62 The distrust of COVID-19 vaccines is partly rooted in historical events of medical cruelty and unethical health research carried out on Black people, the perceived precipitous development of the vaccines, and community members’ lack of access to adequate information about the safety of the vaccines.Footnote 63Footnote 64Footnote 65

A systematic review found that, given that many factors influence vaccine hesitancy, multicomponent interventions that incorporate intensified communication, culturally inclusive informational materials, community outreach and greater accessibility are the most reliable strategies to address this issue.Footnote 66 Black people’s trust in the COVID-19 vaccine and its acceptance can be achieved by involving trusted community and faith leaders,Footnote 67 providing culturally congruent materials and making vaccine information more accessible.Footnote 68Footnote 69 In addition, a change in health policies and programs to garner trust and direct more attention to anti-Black racism will increase vaccine uptake in the Black Canadian community. Employing culturally representative health care personnel to inform Black people in the community can also influence acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine.Footnote 70

The findings from this scoping review suggest that many Black Canadians had difficulties accessing COVID-19-related health care as a result of racism, systemic bias and socioeconomic vulnerabilities. Black Canadians largely perceive the health care system as racially and culturally alienating, and feel that the medical language and cultural barriers had a negative impact on their health care access;Footnote 62 and this was exacerbated at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic revealed the discrimination and racism that have long resulted in poor emotional, mental and physical health outcomes for African-Americans in the USA,Footnote 70 with minority groups tending to receive lower standard of care than White people do, predisposing African-Americans to worse COVID-19 outcomes.Footnote 71

Black Canadians’ relationships with health care personnel have been negatively affected by cultural differences, lack of cultural competence, dependence on the biomedical model and discrimination that has resulted in mistrust.Footnote 72Footnote 73Footnote 74 Culturally sensitive interventions can enhance health care and patient outcomes,Footnote 75Footnote 76 so it is critical to provide Black Canadians with a range of treatment options that incorporate culturally specific supports. Cultural awareness training for health care workers and employment of more Black health care workers would meaningfully contribute to overcoming cultural barriers to health care for Black people in Canada.

Our scoping review also found that Black Canadians and other minority groups encountered mental health distress during the pandemic.Footnote 38Footnote 47Footnote 50Footnote 51 Existing discrepancies in mental health among Black people in Canada and African-Americans in the USA were exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 77Footnote 78 Numerous factors, such as socioeconomic factors and access to mental health services, are responsible for the discrepancy.Footnote 78 Resolving misinformation among Black Canadians through reliable sources and adapting tailored, multimodal and culturally intelligent messaging is important.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first scoping review that focusses on empirical research on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Black people living in Canada. The small number of studies included (n = 17) demonstrates the lack of research on COVID-19 among Black people in Canada, suggesting the need for more studies.

Conclusion

Our review revealed structural barriers, high rates of COVID-19 infections and low uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among Black Canadians, confirming research findings that the COVID-19 pandemic amplified health inequities, generated new barriers to health care, increased mistrust and reduced a sense of belonging among Black people.Footnote 8Footnote 17Footnote 79 More research needs to be conducted to inform policies and programs to address the root causes of inequities.

Some of the studies in this scoping review highlight the need to prioritize the equitable allocation of COVID-19 preventive measures and treatment. COVID-19 prevention strategies that are culturally appropriate and specific should also be made available and accessible. More generally, such initiatives should address the existing barriers associated with structural racism, medical distrust, educational inequities and health inequities. Canadian federal and provincial governments should implement strategies geared towards partnerships with Black-led and Black-focussed community groups to appropriately manage COVID-19 vaccine knowledge gaps and associated distrust factors and barriers, as sensitive and safe education implementation will increase vaccine confidence and herd immunity among Black communities to the benefit of society. Finally, collecting race-based data with the aim of resolving inequities and improving the health and well-being of Black people in Canada is essential to inform policies and address racial discrimination and access to health care services, as well as quality housing and employment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mary Olukotun, PhD Student, Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta, for her invaluable contributions in searching the databases for the reviewed articles.

Funding

This work was funded by the Government of Canada, Department of Heritage Digital Citizenship Program.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions and statement

BS: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, writing – review & editing.

AO: Data curation, formal analysis, writing – original draft.

JK: Data curation, writing – review & editing.

DA: Data analysis, writing – review & editing.

MT: Review & editing.

AR: Review & editing.

AS: Review & editing.

DVM: Review & editing.

KO: Review & editing.

All authors read and agreed on the manuscript. The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

Page details

- Date modified: