Original quantitative research – Estimating the completeness of physician billing claims for diabetes case ascertainment: a multiprovince investigation

HPCDP Journal Home

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: December 2023

ISSN: 2368-738X

Submit a manuscript

About HPCDP

Browse

Previous | Table of Contents | Next

Joellyn Ellison, MPHAuthor reference footnote 1; Yong Jun Gao, MScAuthor reference footnote 1; Kimberley Hutchings, MScAuthor reference footnote 1; Sharon Bartholomew, MHScAuthor reference footnote 1; Hélène Gardiner, MPHAuthor reference footnote 1; Lin Yan, PhDAuthor reference footnote 2; Karen A. M. Phillips, PhDAuthor reference footnote 3; Aakash Amatya, MScAuthor reference footnote 4; Maria GreifAuthor reference footnote 5; Ping LiAuthor reference footnote 6; Yue Liu, MEng, MBAAuthor reference footnote 7; Yao Nie, MScAuthor reference footnote 8; Josh Squires, BScAuthor reference footnote 9; J. Michael Paterson, MScAuthor reference footnote 6; Rolf Puchtinger, MAAuthor reference footnote 5; Lisa Marie Lix, PhDAuthor reference footnote 2

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.43.12.03

This article has been peer reviewed.

Author references

Correspondence

Joellyn Ellison, 785 Carling Ave., Ottawa, ON K1A 0K9; Tel: 613-296-3325; Email: joellyn.ellison@phac-aspc.gc.ca

Suggested citation

Ellison J, Gao YJ, Hutchings K, Bartholomew S, Gardiner H, Yan L, Phillips KAM, Amatya A, Greif M, Liu Y, Nie Y, Squires J, Paterson JM, Puchtinger R, Lix LM. Estimating the completeness of physician billing claims for diabetes case ascertainment: a multiprovince investigation. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2023;43(12):511-21. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.43.12.03

Abstract

Introduction: Previous research has suggested that how physicians are paid may affect the completeness of billing claims for estimating chronic disease. The purpose of this study is to estimate the completeness of physician billings for diabetes case ascertainment.

Methods: We used administrative data from eight Canadian provinces covering the period 1 April 2014 to 31 March 2016. The patient cohort was stratified into two mutually exclusive groups based on their physician remuneration type: fee-for-service (FFS), for those paid only on that basis; and non-fee-for-service (NFFS). Using diabetes prescription drug data as our reference data source, we evaluated whether completeness of disease case ascertainment varied with payment type. Diabetes incidence rates were then adjusted for completeness of ascertainment.

Results: The cohort comprised 86 110 patients. Overall, equal proportions received their diabetes medications from FFS and NFFS physicians. Overall, physician payment method had little impact upon the percentage of missed diabetes cases (FFS, 14.8%; NFFS, 12.2%). However, the difference in missed cases between FFS and NFFS varied widely by province, ranging from −1.0% in Nova Scotia to 29.9% in Newfoundland and Labrador. The difference between the observed and adjusted disease incidence rates also varied by province, ranging from 22% in Prince Edward Island to 4% in Nova Scotia.

Conclusion: The difference in the loss of cases by physician remuneration method varied across jurisdictions. This loss may contribute to an underestimation of disease incidence. The method we used could be applied to other chronic diseases for which drug therapy could serve as reference data source.

Keywords: physician billing, administrative data, data quality, health data, national, surveillance

Highlights

- Some physician visits could be missed because salaried (NFFS) physicians may not shadow bill.

- Data from the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System (CCDSS) were compared to prescription drug data to identify missing diabetes cases.

- How the physician was paid had little impact upon the number and percentage of missed diabetes cases.

- We adjusted the diabetes incidence rates for the missing cases; the largest percentage change between the observed and adjusted rates was for Prince Edward Island (22%) and the smallest was for Nova Scotia (4%).

Introduction

The Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System (CCDSS) is a collaborative network of provincial and territorial surveillance systems, supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). The partnership enables the pooling of population-based data on chronic diseases in Canada with the aim of better understanding the disease burden across the country to support both health promotion and disease prevention efforts and health resource planning. Through access to administrative health data on all residents who are eligible for provincial or territorial health insurance across the country, the CCDSS is able to generate national estimates of incidence, prevalence and associated trends for over 20 chronic diseases.Footnote 1 Administrative health data are extensively used in chronic disease researchFootnote 2Footnote 3Footnote 4Footnote 5Footnote 6Footnote 7Footnote 8Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11 and disease surveillance.Footnote 12Footnote 13Footnote 14Footnote 15Footnote 16

In Canada, physician billing claims are used to remunerate physicians who are paid on a fee-for-service (FFS) basis; these records are also used for various secondary purposes, including disease surveillance. Physicians who are (1) paid a salary, (2) paid on a capitation basis, or (3) paid through some other blended non-fee-for-service (NFFS) mechanism, are frequently required to “shadow bill.”Footnote 17 Shadow billing is an “administrative process whereby physicians submit service provision information using provincial/territorial fee codes; however, payment is not directly linked to the services reported. Shadow billing data can be used to maintain historical measures of service provision based on fee-for-service claims data.”Footnote 17,p.iii

Though the percentage of Canadian physicians paid on a NFFS basis has increased dramatically over the last two decades,Footnote 18 the quality and completeness of shadow billing records remains poorly understood.Footnote 19 For researchers and government agencies that have historically relied upon high-quality physician billing claims data for disease surveillance, systematic under-recording of clinical encounters or patient characteristics via shadow billing could undermine disease estimations.

Using prescription drug data as the reference standard for identifying diabetes incidence, a 2009 Ontario study reported a relative under-identification of diabetes in the physician billing claims data of patients cared for by NFFS family physicians.Footnote 2 A subsequent study investigated the completeness of capture of physician billing claims for FFS and NFFS physicians in Manitoba.Footnote 20 The authors found a loss of physician billing claims associated with physician forms of payment, which resulted in some underestimation of diabetes incidence.Footnote 20 However, to our knowledge, there has been only one multisite studyFootnote 21 to examine the impact of physician remuneration on chronic disease estimation in administrative health data. The purpose of our study was to compare the completeness of capture of incident diabetes among physicians paid by FFS and NFFS methods across multiple Canadian provinces.

Methods

Study design and data sources

The PHAC, in collaboration with all provinces and territories, conducts national surveillance of diabetes to support the planning and evaluation of related policies and programs through the CCDSS.Footnote 22 The CCDSS Data Quality Working Group collaboratively developed the project protocol and completed the analyses. We undertook a multiprovince cohort study using administrative health data from British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador (jurisdictions with access to both the physician registry and prescription drug data) covering the period 1 April 2014 through 31 March 2016.

We used five administrative data sources. The first was physician billing claims, which are completed for physician services. These data contain a physician identification number and diagnosis codes recorded using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), 9th revision, Clinical Modification 23 codes or some variation thereof. The second source was the Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) and MED-ÉCHO, which compile data when a patient is discharged from an acute care facility. These data contain up to 25 diagnosis codes recorded using the ICD, 10th revision, Canadian version (ICD-10-CAFootnote 24). Our reference standard data source for disease incidence was prescription drug data, which contain information for prescription medications dispensed by outpatient pharmacies. Each record contains the date of dispensation, drug identification number and prescriber identification number. The provincial health insurance registry of each jurisdiction was also used. It contains dates of health insurance coverage as well as demographic information such as date of birth, sex and residential or correspondence postal code. Finally, we used the health care provider registry in each province to describe physicians’ characteristics, including specialty and method of payment.

Patient cohort

The patient cohort included all incident diabetes cases identified by prescription drug records among residents aged one year and older in all provinces except Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador, where data were available for residents aged 67 years and older, and Saskatchewan, where data were available for residents aged 65 years and older.Footnote 25 The cohort inclusion criteria were: (1) at least one prescription for a glucose-lowering drug identified by the World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code of A10 in the two-year accrual period from 1 April 2014 to 31 March 2016; (2) continuous health insurance coverage during the two-year period before and the two-year period after the index prescription date, that is, the date that a diabetes prescription medication was first identified in prescription drug records during the observation period; and (3) age of two years or older (or 67 years or older in Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador, and 65 years or older in Saskatchewan) on the index prescription date.

ATC code A10 captures blood glucose–lowering drugs such as metformin and insulins and their analogues, but not supplies such as glucose test strips. To capture incident cases only, individuals were excluded from the study if they had a prescription with an ATC code of A10 within the two-year period prior to their index prescription date. The prescriber identification number associated with the index diabetes medication prescription was linked to the corresponding number in the provider registry to determine physician payment method (i.e. FFS vs. NFFS). Individuals were excluded if the payment method of the provider who made the index prescription was not recorded in the registry and/or if the providers in the provider registry did not match between the CCDSS and prescription drug databases. Women with obstetrical or pregnancy-related diagnosis codes were also excluded.

The cohort was stratified into two mutually exclusive groups: (1) individuals with an index prescription from a FFS physician, and (2) individuals with an index prescription from a NFFS physician. FFS physicians were defined as physicians who received only FFS payments, while NFFS physicians were defined as physicians who received something other than 100% FFS payment.

Denominator

The denominator for the incidence rates included all people with or without diabetes and continuous health insurance coverage during the two-year period before and two-year period after the index prescription date, aged 2 years or older (or 67 years and older in Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador, and 65 years and older in Saskatchewan) on the index prescription date. The denominator for the diabetes incidence rates was tailored to the specific purpose of this study. Therefore, these rates are not comparable to those in other CCDSS publications.

Outcome measures

Using the patient cohort, we identified whether the individual met the diabetes case definition used by the CCDSS.Footnote 26Footnote 27Footnote 28 A case was defined as an individual with one hospitalization or two physician billing claims within two years having an ICD-9-CMFootnote 23 or ICD-9Footnote 29 code of 250 or ICD-10-CAFootnote 24 code of E10, E11, E13 or E14Footnote 27Footnote 28 (diabetes types 1 and 2 could not be distinguished). The sensitivity was 86%, specificity was 97% and positive predictive value (PPV) was 80%.Footnote 28 We defined the case diagnosis date as either the date of hospital discharge or the date of the second qualifying physician billing claim, whichever came first.

Concordance between the administrative data case definition and the reference standard prescription drug claim was evaluated for patients for whom the case diagnosis date fell within the two years preceding or two years following each patient’s index prescription date. To avoid cases of potential gestational diabetes, women aged 10 to 54 were excluded if the qualifying case diagnosis date fell in the 120 days before and up to 180 days following a hospital record containing any obstetrical or pregnancy-related diagnosis codes: ICD-9Footnote 29 641–676, V27; ICD-9 CMFootnote 23 641–679, V27; and ICD-10Footnote 30 and ICD-10-CAFootnote 24 O10-16, O21-95, O98, O99, Z37.

Statistical analysis

The patient cohort was characterized in terms of age group (1–19, 20–64, ≥ 65 years) and sex. The prescribing physicians were characterized by sex, age group (< 35, 35–60, ≥ 61 years) and specialty (other specialist vs. family physician). All physician characteristics were assessed at the index prescription date. The patient cohort and their prescribing physicians were described using frequencies and percentages. A χ2statistic was used to test for differences in characteristics between the FFS and NFFS groups. All analyses were done for each province and overall.

We determined the percentage of individuals identified in the prescription drug data that did not meet the diabetes case definition in the CCDSS; these were classified as missed cases. This assessment was conducted by province and overall, as well as for subgroups defined by age group.

The crude diabetes incidence rate was estimated by dividing the number of cases found using the CCDSS case definition (among the patient cohort) by the denominator (people with continuous health insurance coverage), multiplied by 100 for each province. These rates were for those aged two years and older (67 years and older in Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador, and 65 years and older in Saskatchewan), for the provincial population in the observation period from 1 April 2014 to 31 March 2016 using the CCDSS case definition. Incidence rates were adjusted for the number of FFS and/or NFFS cases found from adding missed cases (first, only FFS, then only NFSS, and finally both FFS and NFSS missed cases to the numerator). Crude rates were used to estimate the completeness of physician billings for diabetes case ascertainment because they provide information about the total magnitude of the effect of missing data within a province.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 or 9.4.Footnote 31 The SAS code was developed by PHAC’s CCDSS operations team, pilot tested by the team in Prince Edward Island and, once finalized, distributed to all participating data centres. The provincial teams then modified the code for their settings, generated the agreed output datasets and submitted them to PHAC, which then pooled the results from all provinces. All counts and related statistics greater than 0 and less than 5 were suppressed to avoid residual disclosure and to provide more reliable estimates. Also, to calculate the rates, all counts were rounded at random using a base of 10, and therefore individual cell values may not add up to the totals.

Results

The overall cohort comprised 86 110 patients (43 770 FFS and 42 350 NFFS; 43 650 males and 42 070 females) and 17 665 physicians (6054 FFS and 11 611 NFFS; 10 412 males and 7250 females). The provincial patient cohorts ranged in size from 1460 in Prince Edward Island to 31 620 in Ontario (Table 1). About half (50.8%) of patients received their index prescription from a FFS physician. On average, each FFS physician prescribed to 7.2 patients and each NFFS physician prescribed to 3.6 patients (data not shown).

| Province | 1–19 years | 20–64 years | ≥ 65 yearsFootnote b | Age 1+ | Total (FFS + NFFS) |

Total (%) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFS | NFFS | FFS + NFFS | % | FFS | NFFS | FFS + NFFS | % | FFS | NFFS | FFS + NFFS | % | FFS | % | NFFS | % | |||

| British Columbia | 260 | 310 | 580 | 2.2 | 16 090 | 2 980 | 19 060 | 71.3 | 6 040 | 1 070 | 7 110 | 26.6 | 22 380 | 83.7 | 4 360 | 16.3 | 26 750 | 100.0 |

| SaskatchewanFootnote b | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 090 | 780 | 2 880 | 100.0 | 2 100 | 72.9 | 780 | 27.1 | 2 880 | 100.0 |

| Manitoba | 330 | 40 | 360 | 2.3 | 9 110 | 2 630 | 11 740 | 75.6 | 2 860 | 580 | 3 440 | 22.2 | 12 290 | 79.1 | 3 240 | 20.9 | 15 530 | 100.1 |

| OntarioFootnote b | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 600 | 30 010 | 31 620 | 100.0 | 1 600 | 5.1 | 30 010 | 94.9 | 31 620 | 100.0 |

| Prince Edward Island | — | 20 | 20 | 2.1 | 100 | 910 | 1 010 | 69.2 | 60 | 380 | 420 | 28.8 | 160 | 10.5 | 1 310 | 89.5 | 1 460 | 100.1 |

| Nova Scotia | 20 | 40 | 50 | 0.9 | 1 020 | 820 | 1 840 | 33.6 | 2 180 | 1 420 | 3 600 | 65.7 | 3 210 | 58.5 | 2 280 | 41.5 | 5 480 | 100.2 |

| Newfoundland and LabradorFootnote b | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | — | 0 | N/A | N/A | 2 020 | 380 | 2 400 | 100.0 | 2 020 | 84.3 | 380 | 15.7 | 2 400 | 100.0 |

| Total | 610 | 420 | 1 020 | N/A | 26 310 | 7 330 | 33 650 | N/A | 16 850 | 34 600 | 51 450 | N/A | 43 770 | 50.8 | 42 350 | 49.2 | 86 110 | N/A |

The majority of the patients were 65 years and older, which was anticipated given the composition of the patient cohorts from Saskatchewan, Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador. The largest number of FFS patients (26 310) were aged 20 to 64, while the largest number of NFSS patients (34 600) were 65 years and older (Table 1). There was almost no difference in the sex distribution of FFS and NFFS patients; however, the type of remuneration method was statistically significantly different in at least one physician age groupt (χ2 = 123.546; p < 0.001; df = 2; data not shown).

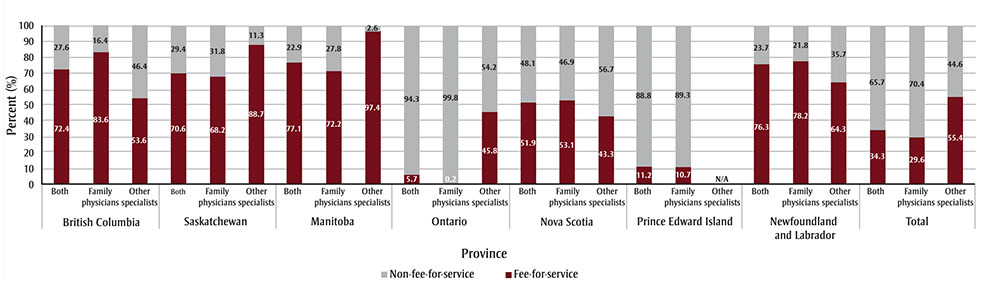

According to our definition of FFS remuneration (100% of payments on FFS basis), Manitoba had the largest percentage of FFS physicians (77.1%), while Ontario had the smallest (5.7%; Figure 1). British Columbia had the largest percentage (83.6%) of family physicians classified as FFS physicians, while Ontario had the smallest (0.2%). Nova Scotia had the highest percentage (56.7%) of NFSS physician specialists and Manitoba had the lowest (2.6%; Figure 2).

Figure 1 - Text description

| Province | Non-fee-for-service | Fee-for-service |

|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 27.6 | 72.4 |

| Saskatchewan | 29.4 | 70.6 |

| Manitoba | 22.9 | 77.1 |

| Ontario | 94.3 | 5.7 |

| Prince Edward Island | 88.8 | 11.2 |

| Nova Scotia | 48.1 | 51.9 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 23.7 | 76.3 |

| Total | 44.6 | 55.4 |

Figure 2 - Text description

| Province | Non-fee-for-service | Fee-for-service | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both | Family physicians | Other specialists | Both | Family physicians | Other specialists | |

| British Columbia | 27.6 | 16.4 | 46.4 | 72.4 | 83.6 | 53.6 |

| Saskatchewan | 29.4 | 31.8 | 11.3 | 70.6 | 68.2 | 88.7 |

| Manitoba | 22.9 | 27.8 | 2.6 | 77.1 | 72.2 | 97.4 |

| Ontario | 94.3 | 99.8 | 54.2 | 5.7 | 0.2 | 45.8 |

| Nova Scotia | 48.1 | 46.9 | 56.7 | 51.9 | 53.1 | 43.3 |

| Prince Edward Island | 88.8 | 89.3 | N/A | 11.2 | 10.7 | N/A |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 23.7 | 21.8 | 35.7 | 76.3 | 78.2 | 64.3 |

| Total | 65.7 | 70.4 | 44.6 | 34.3 | 29.6 | 55.4 |

Individuals identified as a case of diabetes in the prescription drug data who did not meet the CCDSS administrative diabetes case definition were classified as missed. Overall, 13.5% of those diagnosed were missed. Prince Edward Island had the highest rate of missed cases (17.6%) and Nova Scotia had the lowest (4.8%). Quebec data were not shown, as the data by physician remuneration type were not available; however, 19.3% missed cases were observed. For FFS and NFFS physicians, the overall percentages were 14.8% and 12.2%, respectively. However, the differences varied widely by province, ranging from −1.0% to 29.9% in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador, respectively. For most provinces, the percentage of missed cases was greater for NFFS than FFS physicians, with the exceptions of OntarioFootnote 32 and Prince Edward Island. Prince Edward Island had the highest percentage of missed cases (26.7%) from FFS physicians, while Nova Scotia had the lowest (3.8%). For NFFS physicians, Newfoundland and Labrador had the highest percentage of missed cases (36.8%). Nova Scotia had the lowest percentage of missed cases (4.8%) among NFFS physicians (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Text description

| Province | Fee-for-service | Non-fee-for-service | Percent change from fee-for-service to non-fee-for-service |

|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 16.7 | 18.3 | -1.6% |

| Saskatchewan | 8.1 | 10.3 | -2.2% |

| Manitoba | 16.1 | 19.7 | -3.1% |

| Ontario | 16.9 | 10.5 | 37.9% |

| Prince Edward Island | 26.7 | 17.6 | 9.1% |

| Nova Scotia | 3.8 | 4.8 | -1.0% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 6.9 | 36.8 | 29.9% |

| Total | 14.8 | 12.2 | N/A |

For patients aged 1 to 19 years for whom the prescribing physician was remunerated by the FFS method, 50% of the cases were missing in Prince Edward Island. Manitoba had the lowest (15.2%) for this physician type and age group. Prince Edward Island had the highest percentage (22.2%) of missed cases among the 20 to 64 age group, while Nova Scotia had the lowest (5.9%). For those aged 65 years and older, Prince Edward Island had the highest percentage (20.0%) of missed cases, while Nova Scotia had the lowest (2.8%).

For patients aged 1 to 19 years for whom the prescribing physician was remunerated by the NFFS method, British Columbia had the highest percentage (53.3%) of missed cases and Nova Scotia had the lowest (3.2%). British Columbia had the highest percentage (23.1%) of missed cases among the patients aged 20 to 64 for whom the prescribing physician was paid by NFFS methods, while Nova Scotia had the lowest (7.4%). For patients 65 years of age or older for whom the prescribing physician was remunerated by NFFS methods, Newfoundland and Labrador had the highest percentage (36.8%) of missed cases, while Nova Scotia had the lowest (4.2%; Figure 4).

Figure 4 - Text description

| Province | Fee-for-service | Non-fee-for-service | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–19 years | 20–64 years | ≥ 65 years | 1–19 years | 20–64 years | ≥ 65 years | |

| British Columbia | 40.7 | 20.6 | 5.1 | 53.3 | 23.1 | 3.8 |

| Saskatchewan, data were only available for ≥ 65 years | N/A | N/A | 8.1 | N/A | N/A | 10.3 |

| Manitoba | 15.2 | 19.2 | 6.3 | 50.0 | 20.2 | 15.8 |

| Ontario, data were only available for ≥ 67 years | N/A | N/A | 16.9 | N/A | N/A | 10.5 |

| Nova Scotia | 16.7 | 5.9 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 7.4 | 4.2 |

| Prince Edward Island | 50.0 | 22.2 | 20.0 | 9.1 | 18.7 | 18.5 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador, data were only available for ≥ 67 years | N/A | N/A | 6.9 | N/A | N/A | 36.8 |

| Total | 25.0 | 19.6 | 6.8 | 20.0 | 19.6 | 10.5 |

Figure 5 presents the diabetes incidence ratesFootnote * adjusted for cases missed by both FFS and NFFS methods among those aged one year and older (72% of the denominator), except for in Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador, where data were reported for residents aged 67 years and older, and in Saskatchewan, where data were reported for residents aged 65 and older. Ontario and Saskatchewan had the highest incidence rate (1.5% for both), adjusted from 1.4% in Ontario and 1.4% in Saskatchewan. Newfoundland and Labrador experienced the lowest incidence rate of 0.43%, adjusted from the observed rate of 0.38%. The largest percentage change between the observed and adjusted rates was for Prince Edward Island (22.5%) and the smallest was for Nova Scotia (4.7%).

Figure 5 - Text description

| Province | Observed | Adjusted for cases missed by NFFS | Adjusted for cases missed by FFS | Adjusted for cases missed by both FFS and NFFS physicians |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 1.01 |

| British Columbia, 1+ years | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.84 |

| Saskatchewan, data were only available for ≥ 65 years | 1.40 | 1.45 | 1.50 | 1.54 |

| Manitoba, 1+ years | 0.92 | 0.97 | 1.06 | 1.11 |

| Ontario, data were only available for ≥ 67 years | 1.38 | 1.53 | 1.39 | 1.54 |

| Prince Edward Island, 1+ years | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.52 |

| Nova Scotia, 1+ years | 0.75 | 0.89 | 0.76 | 0.91 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador, data were only available for ≥ 67 years | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.43 |

Discussion

The aim of this study was to estimate the completeness of the physician billings data for estimating chronic disease. Overall, 13.5% of cases were missed. We determined that the overall percentage of missed cases found among FFS physicians was generally similar to that for NFSS physicians (14.8% vs. 12.2%, respectively). However, differences varied by province; for example in Nova Scotia, the missing rates were very similar for FFS and NFFS (3.8% and 4.8%, respectively); whereas the rates were very different in Newfoundland and Labrador (6.9% and 36.8%, respectively), where physicians do not practise shadow billing.Footnote 33

We expected some missed cases among FFS physicians. Some physician billing claims may not be captured in claims databases, possibly through administrative error or failure to submit claims. Compared to NFFS physicians, FFS physicians may have seen more patients with other health problems that were not recorded because there was not enough room on the claim form.Footnote 32 One potential source of discordance between diabetes prescriptions and presence of diagnostic information on physician billing claims is misclassification bias, as some FFS physicians may have a NFFS component to their practice or may have changed to NFFS remuneration. Hybrid payment methods and changes in payments are not always captured in the provincial provider registries and may vary across provinces. Heterogeneity across provinces in the capture of remuneration method and shadow-billed claims was reported in a previously published paper.Footnote 19

The percentage of missed cases was higher in the younger physician age groups, compared to older age groups, for both FFS and NFFS physicians, suggesting that the sensitivity of ascertainment differs based on the age of the physicians. Finally, the physicians who prescribed the initial glucose-lowering therapy may not be the primary care provider, or therapy may have been discontinued, or it may have been initiated for reasons other than diabetes.

Our study found similarities and differences with a study conducted in Manitoba.Footnote 20 Previously, Lix et al. reported that a smaller percentage of FFS physicians’ cases were missing a diabetes diagnosis: 14.9% vs. 18.7% for NFFS physicians. In our study, the percentage of missed cases among FFS and NFFS physicians was more similar overall (14.8% and 12.2%, respectively), although the percentage remained relatively smaller among FFS physicians in Manitoba (16.1%, compared with 19.7% for NFSS physicians). The Manitoba study also found a higher percentage of missed diagnoses in the younger age group than the older age group. We also found that a greater percentage of FFS patients were younger, whereas a greater percentage of NFSS patients were older. In the previous Manitoba study,Footnote 20 the percentage change between the observed and adjusted results for cases missed by both FFS and NFFS diabetes incidence rates was 15.8%, while in our study, the percentage change was 20.2% for Manitoba.

Underestimation of disease incidence when using administrative data (i.e. hospital discharge abstracts and physician billing claims) may occur because of different billing practices and policies. For example, if a jurisdiction has a large number of missing cases from NFFS physicians, it may mean that they are not practising shadow billing. Thus, it may be important to monitor missing cases by remuneration type over time to consider any adjustments or data quality documentation for reporting.

It is also important to consider strategies for adjusting prevalence and incidence estimates for possible underestimation. One strategy may be to use prescription drug data to estimate the physician billing claims records underestimation for disease surveillance, although using this data source alone may not be sufficient.Footnote 5 When prescription drug data were used, for example, based on the CCDSS case definition, we estimated a 0.9% crude diabetes incidence rate in the Manitoba population aged 1 year and older during the study period (Figure 5). However, when cases identified in the prescription drug data were used to adjust for underestimation, the incidence rate increased to 1.1%.Footnote * An additional strategy may be to use other population-based data such as electronic medical records, which are increasingly being adopted in population-based chronic disease research and surveillance studies to adjust for underestimation.Footnote 34

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. It included data from multiple provinces, which improves the generalizability of the findings relative to previous single-province studies. Also, it uses data from the CCDSS, which uses a validated standardized case definition for diabetes. Additionally, the method could be applied to other heath conditions for which the sensitivity and specificity of prescription drug data for case capture is high.

The study also has limitations. First, cases that were missed may have been overestimated because women of childbearing age with gestational diabetes were not excluded from the prescription drug databases of British Columbia, Manitoba, Quebec, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia (72% of the denominator). However, the overestimation was likely minimal, considering the rate of gestational diabetesFootnote 35 and considering that a significant proportion of the cohort were either males or aged 65 and over.

Second, physicians were classified as either FFS or NFFS, but many physicians are now paid through blended remuneration schemes or may have changed from one method to another over the study period. However, given that we used only two fiscal years of diabetes prescription information, the possibility of physicians switching payment method during the study period may be minimal.

Third, the results may be sensitive to the definitions used to ascertain missed and non-missed cases. We examined the two-year periods before and after the index prescription date; these periods were chosen to align with the observation period required by the CCDSS diabetes case definition. Previous research has shown that when prescription drug data were added to the CCDSS diabetes case definition in the adult population, the sensitivity was 90.7%, specificity was 97.5% and PPV was 81.5%,Footnote 5 versus 89.3%, 97.6% and 81.9%,Footnote 5 respectively, without prescription claims. Other research showed that 5.6% of diabetes cases were missed when prescription claims records were excludedFootnote 36 and Tu et al. found that when a combination of prescriptions for antidiabetic medications and laboratory tests results is used, patients with diabetes can be identified within an electronic medical record (EMR) with accuracy similar to administrative data.Footnote 4 While it is possible that individuals without diabetes might receive a prescription for a diabetes drug, the contribution of these false positives to the percentage of missed cases is unknown.

Fourth, our findings are not applicable to diabetes patients treated with lifestyle modification only, as they are not captured in prescription drug data. Fifth, the completeness of prescription drug data varied as Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador data were available for patients aged 67 and older and Saskatchewan data for patients aged 65 and older. Sixth, while age-standardized rates were not required to examine the impact of missing physician billings within a province, readers should use caution for cross-jurisdictional comparisons.

Conclusion

We adopted a population-based approach to assessing the completeness of physician billing claims data for chronic disease surveillance. We relied upon prescription drug data to evaluate completeness; this source is known to be sensitive for diabetes case ascertainment.Footnote 5 Our study showed that when using prescription drug data to assess the completeness of cases in the CCDSS, there is loss of data. Overall, the percentage of missed cases was comparable across physician remuneration methods. However, this varied widely by province. Where it did occur, loss of data may have contributed to underestimation of disease incidence. The method we used could be applied over time and in other jurisdictions to address systematic differences in shadow billing practices, as well as to other chronic diseases for which drug therapy could serve as reference data source.

Acknowledgements

These data were made possible through collaboration between PHAC and the respective provincial and territorial governments of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Northwest Territories, Yukon and Nunavut. Parts of this material are based on data or information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI).

Dr. Lisa Marie Lix is supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Methods for Electronic Health Data Quality. The authors acknowledge the contributions of Cynthia Robitaille, Songul Bozat-Emre and Prajakta Awati. In memory of Phillippe Gamache.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’s contributions

JE—conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. YJG—formal analysis, methodology, validation. KH—conceptualization, methodology, project administration, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. SB—conceptualization, methodology, project administration, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. HG—visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. LY—formal analysis, methodology. KAMP, AA, MG, PL, YL, YN, JS, RP—data curation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing—review and editing. LML—conceptualization, methodology, supervision, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. JMP—methodology, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing.

Statement

The analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement by PHAC, CIHI, the provincial/territorial governments or the Government of Canada is intended or should be inferred.

Page details

- Date modified: