North American Preparedness for Animal and Human Pandemics Initiative

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 584 KB, 21 page)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: 2024-10-23

Table of contents

- Executive summary

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Scope of trilateral collaboration

- Chapter 3: Governance

- Chapter 4: Communications, protocols and triggers

- Chapter 5: Key areas for collaboration based on trilateral lessons learned from COVID-19 and other health security emergencies

- Annex: Acronym list

- References

Executive summary

Spanning over three decades, Canada, Mexico, and the United States have shared a common vision to strengthen regional health security.Footnote 1 In 2007, the North American leadersFootnote 2 launched the North American Plan for Avian and Pandemic Influenza (NAPAPI).Footnote 3 This plan was revised and relaunched in 2012 after the lessons learned from the H1N1 (2009) influenza pandemic as the North American Plan for Animal and Pandemic Influenza (also NAPAPI), a comprehensive, regional, and cross-sectoral framework to prepare for and respond to outbreaks of animal and human influenza pandemics.Footnote 4

During the last decade, NAPAPI has been a key cross-sectoral platform for regional health security discussions and collaboration. It has not only served as the forum to address several highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreaks in North America but also to prepare jointly for the potential spread or impact to our region of the Middle East’s MERS-CoV outbreaks, the Ebola outbreaks in Africa, the Zika outbreak in the Americas, the Fukushima nuclear disaster, and accidental release of radiological materials in the United States, among others.

Despite this close collaboration, COVID-19 exposed a new set of cross-sectoral challenges and opportunities in each country and in the region. Based on this, during the 2021 and 2023 North American Leaders’ Summit (NALS), the leaders of the three countries committed to ensuring that we are ready to face the next pandemic and other health threats in our region by re-envisioning and updating the 2012 NAPAPI based on lessons learned from COVID-19 and other health security events in the last decade.Footnote 5

This revised NAPAPI, now the North American Preparedness for Animal and Human Pandemics Initiative (NAPAHPI), is formally a “flexible, scalable, and cross-sectoral platform to strengthen regional prevention, preparedness for, and response to a broader range of health security threats that include pandemics of any origin and beyond.”Footnote 6 In brief, NAPAHPI is intended to facilitate collaboration using a One Health approach as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “an integrated, unifying approach to balance and optimize the health of people, animals and the environment” that “mobilizes multiple sectors, disciplines and communities at varying levels of society to work together.”Footnote 7

- During public health emergencies or in anticipation of potential emergencies, the scope of NAPAHPI includes collaborating on any disease or the public health impacts of any event that needs trilateral cross-sectoral assessment, preparedness, and/or rapid response actions based on a set of guiding questions/decision-making process.

- During non-emergency periods, NAPAHPI activities focus on preparedness efforts and development of capacities and capabilities as identified through the trilateral lessons learned from COVID-19 and other health security events.

Chapter 1: Introduction

North American Plan for Animal and Pandemic Influenza (NAPAPI)

NAPAPI is a long-standing trilateral collaboration framework among Canada, Mexico, and the United States first launched in 2007 to prepare for human and avian influenza viruses with pandemic potential.Footnote 8 During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic and at the 2009 North American Leaders’ Summit (NALS), the leaders of the three countries committed to a continued and deepened cooperation on pandemic influenza preparedness.Footnote 9

In 2011, after conducting an in-depth trilateral lessons learned review from the pandemic, NAPAPIFootnote 10 was revised to cover influenza viruses of any animal origin and was relaunched by the North American leaders at the 2012 NALS.Footnote 11 The new framework was envisioned as a comprehensive, regional, and cross-sectoral health security framework outlining how the three countries intended to strengthen North America’s emergency response capacities, as well as trilateral collaboration mechanisms and capabilities to assist each other, and ensure a rapid and coordinated response to outbreaks of animal influenza or an influenza pandemic. Of note, the 2012 NAPAPI was praised by the WHO and G7 partners as a model for regional collaboration in alignment with the implementation of collaboration among neighboring countries in accordance with the spirit of the International Health Regulations (IHR) (2005).Footnote 12

NAPAPI established a Senior Coordinating Body (SCB) and a Health Security Working Group (HSWG) as the two governance bodies in charge of implementing trilateral actions. These trilateral cross-sectoral bodies are composed of senior leaders/decision-makers and policy/subject-matter experts, respectively, from the animal health/agriculture, human health, security, and foreign affairs sectors. Since 2007, the SCB and the HSWG have met regularly to implement the NAPAPI work plan and to discuss the regional response to several highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreaks and also to hold trilateral discussions for actions to prepare and respond to other health security threats to North America beyond influenza, such as the MERS-CoV outbreaks in the Middle East, the Ebola outbreaks in Africa, the Zika outbreak in the Americas, the Fukushima nuclear disaster, and the accidental release of radiological materials in the United States, among others. During all these events, NAPAPI has been a key platform for regional health security discussion and action where sectors in addition to health could share situational awareness and best practices, conduct joint exercises, and develop joint emergency communications and response plans.

NAPAPI during COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that there are myriad political, legal, regulatory, policy, preparedness, and response challenges that can be best addressed through a stronger regional coordinated approach for prevention, preparedness, and response. NAPAPI experts engaged during the COVID-19 pandemic by regularly convening the HSWG to ensure information sharing and exchange of best practices on various issues including clinical and epidemiological information sharing, disease modeling, foresight and risk analysis, supply chains, diagnostics development and utilization policies, medical countermeasures research and development, agricultural/food processing workers safety, and research protocols/diagnostics for farmed and agricultural animals as well as pets, among others. However, COVID-19 exposed several policy and technical preparedness gaps, including the need for senior-level, policy engagement and discussion to address the pandemic with a more coordinated, regional, and cross-sectoral approach. The need for trilateral alignment and/or coordination in developing and implementing national policies regarding border measures, supply chains, testing, availability of vaccines/other prophylaxis and therapeutics, and risk communications, among others was clearly exposed. These issues demonstrated the interconnectedness of our populations and the fact that, indeed, pathogens know no borders. Therefore, the North American leaders agreed that the region needed to review and strengthen the commitments made during the 2012 NAPAPI to extend the focus of the plan from influenza viruses to other pathogens, agents, or events that can pose a threat to health security in the region.

A joint vision for regional health security: North American Preparedness for Animal and Human Pandemics Initiative (NAPAHPI)

Based on the above, during the 2021 NALS, the leaders affirmed their vision of a world safe and secure from global health threats posed by infectious diseases. They committed to ensuring that we are ready to face the next pandemic and other health threats in our region by re-envisioning and updating the 2012 NAPAPI based on lessons learned from COVID-19 and other health security events in the last decade.Footnote 13 In 2023, after the SCB and the HSWG conducted a review of the lessons learned and made recommendations at the policy and technical levels, North American leaders agreed to develop and launch a new, revised NAPAPI as a flexible, scalable, and cross-sectoral platform to strengthen regional prevention, preparedness and response to a broader range of health security threats that include influenza and beyond.”Footnote 14

This new initiative, NAPAHPI, reflects the intent of the three countries across multiple sectors to develop and implement guidelines, capacities, and capabilities for the leadership, policy, and operational levels in each country to work together through a flexible and scalable framework when there is a need for concerted action to protect the region from pandemics and/or any health security threat. This new approach does not intend to replace or duplicate any national plan, bilateral arrangements, or international initiatives in which the three countries already participate to address their obligations under the IHR (2005) and to strengthen the global health security architecture. Instead, NAPAHPI provides a renewed opportunity for complementary trilateral collaboration and supports a vision for North America’s joint ability to prevent and mitigate, prepare for, respond to, and recover from pandemics and events that pose a threat to its health security.

Chapter 2: Scope of trilateral collaboration

After the trilateral lessons learned process conducted in 2022 based on COVID-19 and other health security emergencies that North America faced in the last decade, NAPAHPI is a flexible framework that facilitates collaboration on any health security threat to the region that requires trilateral consideration and action with a One Health approach. This means following “an integrated, unifying approach to balance and optimize the health of people, animals and the environment” that “mobilizes multiple sectors, disciplines, and communities at varying levels of society to work together”.Footnote 15

- During public health emergencies or in anticipation of potential health emergencies, the scope of NAPAHPI includes collaborating on any disease or the public health impacts of any event that needs trilateral cross-sectoral assessment, preparedness, and/or rapid response actions based on a set of guiding questions/decision-making process (as shown in Figure 1).

- During non-emergency periods, NAPAHPI activities focus on preparedness efforts and development of generic capacities and capabilities as identified through the Trilateral Lessons Learned from COVID-19 and other Health Security Events.

International Health Regulations (2005) [IHR (2005)] as a legal framework for regional health security collaboration

NAPAHPI’s renewed scope to address health security threats in a collaborative regional manner stemmed from the recognition that the health, wellbeing of societies, supply chains, and economies of Canada, Mexico, and the United States are fully intertwined. The three countries are States Parties to the IHR (2005) as an international legally binding framework for global health security. NAPAHPI is a regional collaboration in the full spirit of compliance with IHR (2005) and in the context of Article 44.1 by which States Parties “undertake to collaborate with each other, to the extent possible, in: (a) the detection and assessment of, and response to, events as provided under these Regulations; (b) the provision or facilitation of technical cooperation and logistical support, particularly in the development, strengthening, and maintenance of the public health capacities required under these Regulations; (c) the mobilization of financial resources to facilitate implementation of their obligations under these Regulations; and (d) the formulation of proposed laws and other legal and administrative provisions for the implementation of these Regulations.” Moreover, Article 44.3 states that “collaboration under this Article may be implemented through multiple channels, including bilaterally, through regional networks and the WHO regional offices, and through intergovernmental organizations and international bodies.”

Since the IHR (2005) entered into force in 2007 and since the launch of the first NAPAPI that same year, the three countries have strived to maintain a close collaboration in health security matters, in particular in those that need close information sharing regionally and a cross-sectoral approach. For example, since 2007 the National IHR Focal Points (IHR NFPs) of Canada, Mexico, and the United States have simultaneously informed each other of notifications made to the WHO/Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) of events that may constitute a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC),Footnote 16 made pursuant to the IHR (2005). The new scope of the NAPAHPI goes beyond influenza pandemics and recognizes the all-hazards nature of the IHR (2005). Thus, it commits to continue strong, trilateral collaboration to assess and address any human, animal, or environmental health threats or events (including zoonotic disease outbreaks notified to the World Organisation for Animal Health [WOAH])Footnote 17 that can pose a potential or actual risk to the health security of North America according to the criteria in the decision-making tool shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 - Text description

The NAPAHPI decision-making tool is a decision tree which provides guidance on appropriate actions under various scenarios.

The decision tree provides criteria to identify whether an event could pose a potential or actual risk to the health security of North America, beginning with the following descriptions:

“Any threat or event reported to the World Health Organization (WHO), under the International Health Regulations (2005)”a , or, “Any other threat or event of potential human or animal health concern, regardless of origin or source (including diseases notified to the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH).”b

If either of these conditions are met, the next question to be considered is:

“Does the threat or event pose a high risk of spreading to or within North America?”

The decision tree is then divided as follows:

If Yes or Maybe:

Convene the Health Security Working Group (HSWG) and/or ad-hoc sub working groups to assess the need for trilateral collaboration and action. As needed, make recommendations to the Senior Coordinating Body (SCB) for high-level engagement and actions.c

If No:

Is there a risk that the threat or event abroad can impact human health and/or animal health, environment, travel, and/or trade in North America?

- If the answer is Yes, the decision tree leads back to the action previously provided for a positive answer, which entails the need to convene the HSWG.

- If the answer is No, it is then considered that a condition of high risk to North America does not exist; the end of this branch of the tree states that “Trilateral cross-sectoral leads [should] continue to monitor the threat or event as needed applying this algorithm.”

The decision tool also provides some footnotes with additional information, as follows:

- When one of the three countries notifies events to WHO through the National IHR Focal Points (i.e., under IHR article 6), it will simultaneously notify the other two countries.

- This is not an exhaustive list of potential scenarios or considerations; additional unexpected situations may trigger NAPAHPI action.

- When considering the risk posed by an event, the three countries may also consider other agreements or initiatives in place to inform their collective assessment and guide a decision about NAPAHPI action.

Chapter 3: Governance

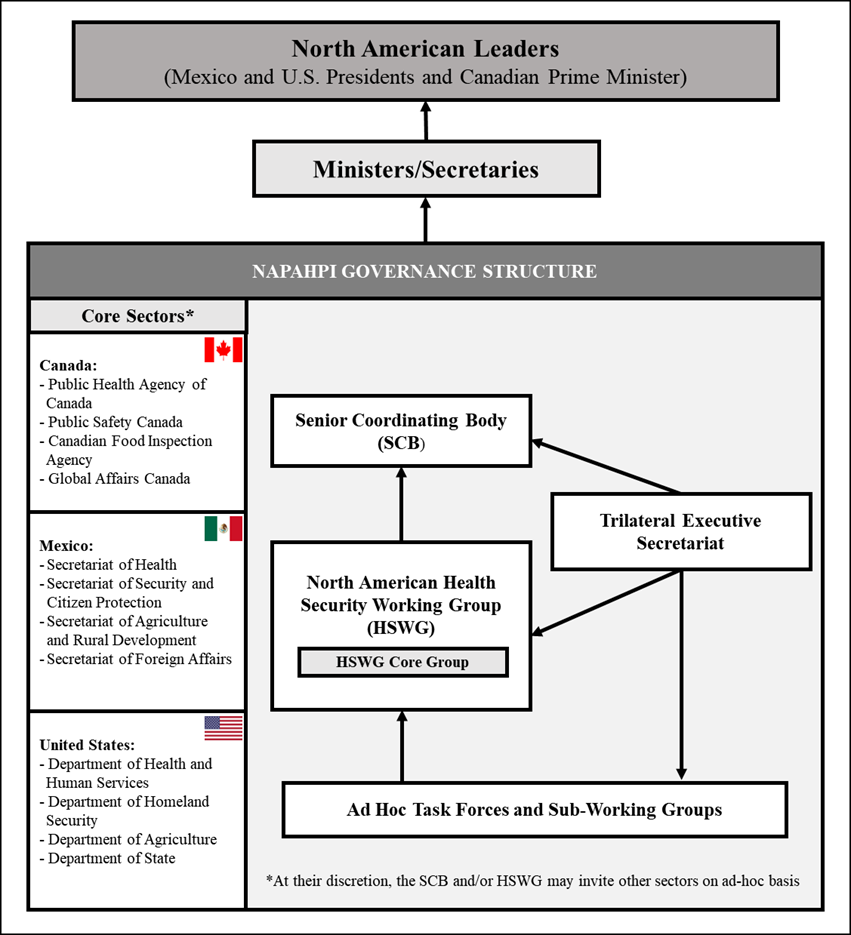

NAPAHPI is governed by the SCB, the HSWG, and a Trilateral Executive Secretariat. These bodies are composed of members from the human health, animal health/agriculture, security, and foreign affairs sectors of the three countries, which together and as appropriate report through their senior-level leadership (ministers/secretaries) to the North American leaders.

The principal agencies representing these sectors in the governance structure are:

Canada: Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC)Footnote 18, Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA),Footnote 19 Public Safety Canada (PS),Footnote 20 and Global Affairs Canada (GAC).Footnote 21

Mexico: Secretariat of Health (SALUD),Footnote 22 Secretariat of Agriculture and Rural Development (SADER),Footnote 23 Secretariat of Foreign Affairs (SRE),Footnote 24 and Secretariat of Security and Citizen Protection (SSPC).Footnote 25

United States:Department of Health and Human Services (HHS),Footnote 26 Department of Homeland Security (DHS),Footnote 27 Department of Agriculture (USDA),Footnote 28 and Department of State (DOS).Footnote 29

North American Senior Coordinating Body (SCB)

The SCB consists of twelve senior officials at the level of undersecretary, assistant secretary, assistant deputy minister, or their designees, from the federal human health, animal health/agriculture, security, and foreign affairs sectors of the three countries. The human health sector senior officials serve as co-chairs of the SCB, with the principal chair rotating every two years among the three countries.

Roles and responsibilities

- Serve as a high-level forum to discuss and facilitate trilateral collaboration in preparedness for and response to public health emergencies within the scope of NAPAHPI.

- Identify and prioritize activities, gaps, and areas for collaboration to strengthen North American health security.

- Promote cross-sectoral collaboration among NAPAHPI sectors and others as needed.

- Oversee the activities of the HSWG and Trilateral Executive Secretariat to ensure timely development, appropriate coordination, and completion of activities.

- Advise their respective ministers, secretaries, and North American leaders, as appropriate.

The SCB intends to meet at least twice a year or as convened by the co-chairs on as-needed basis. Meetings may be held in person or virtually.

North American Health Security Working Group (HSWG)

The HSWG reports to the SCB and consists of policy and technical subject-matter experts from the federal human health, animal health/agriculture, security, and foreign affairs sectors of the three countries. Representatives from other sectors such as the environment, defense, commerce, Indigenous population services, transportation, etc., should be invited to participate in meetings when issues within their areas of expertise or legal authority are being considered as appropriate. The HSWG is co-chaired by two health sector representatives from the country serving as principal chair of the SCB.

Roles and responsibilities

- Develop and execute a comprehensive, coordinated and evidence-based approach to plan for and respond to public health emergencies within the scope of NAPAHPI and under the guidance of the SCB.

- Advise the SCB and facilitate the implementation of activities that strengthen information sharing, collaboration, interoperability, and public health capacity building on emergency preparedness for and response to public health emergencies within the scope of NAPAHPI and the agreed upon areas for trilateral work.

- Serve as the technical and policy-level group in the event of a pandemic or public health emergency.

The HSWG intends to meet at least every two months or as convened by the HSWG co-chairs on an as-needed basis. Meetings may be held in person or virtually.

HSWG core group

Within the HSWG, the Core Group consists of two representatives from each sector (human health, animal health/agriculture, security, and foreign affairs sectors) per country and is led by the HSWG co-chairs.

Roles and responsibilities

- Coordinate the review, revision, and clearance of documents produced within NAPAHPI.

- Brief senior leadership (including SCB members) and experts from their sectors as appropriate.

- Coordinate with other sectors, as appropriate, regarding the development and completion of implementation actions, particularly those that may affect matters within their areas of expertise or legal authority.

- Oversee the creation, activities, and participation of their sectors in any ad hoc task forces and sub-working groups as deemed necessary by the SCB or the HSWG.

Ad hoc task forces and sub-working groups

The SCB or HSWG may establish ad hoc task forces or sub-working groups to address specific and time-limited issues for preparedness and response purposes. The leads for these groups are designated by the HSWG Co-chairs.

Roles and responsibilities

- Serve as a technical and policy-level expert group.

- Provide advice and recommendations to the HSWG and SCB as appropriate.

Trilateral Executive Secretariat

The Trilateral Executive Secretariat consists of the two health sector representatives from the HSWG Core Group plus support staff from the health sector of each country. In addition, each country’s membership within the Trilateral Executive Secretariat serves as their own country’s secretariat.

The HSWG Co-chairs lead the Trilateral Executive Secretariat, and one of the country's secretariats manages the day-to-day operations rotating every two years among the three countries, or as decided trilaterally.

Roles and responsibilities

- Support the Chairs of the SCB, coordinate SCB meetings and prepare reading material ahead of meetings.

- Support HSWG and SCB members, develop and retain records of meeting and summaries of conclusions/decisions. Distribute to HSWG and SCB members as soon as possible following meetings.

- Provide a coordinated approach to manage NAPAHPI workplan activities and meetings, develop agendas, guidelines, readouts, etc.

- Convene meetings of the HSWG and SCB as needed at the discretion of the HSWG o-chairs or the SCB.

Coordination with ministers/secretaries and presidents/prime minister

The SCB, HSWG, and the Trilateral Executive Secretariat are in charge of apprising and advising their ministers/secretaries on NAPAHPI work, and through them and as appropriate to their leaders (Prime Minister of Canada and Presidents of Mexico and the United States), including providing advice and recommendations during emergencies.

Participation of other sectors

As learned during COVID-19 and other emergencies, each type of event is different and depending on its nature, the SCB and/or the HSWG can and should invite other sectors to participate in NAPAHPI when circumstances warrant. They can request the participation of sectors such as defense, commerce, transportation, emergency management, wildlife, environment, etc., as appropriate. In addition, they can and should call on private sector stakeholders particularly those associated with supply chains, medical countermeasures, research and development, critical infrastructure, and transportation, among others.

Figure 2 - Text description

The NAPAHPI Governance structure describes the relationships between the various organizations that are members of NAPAHPI.

The structure is headed by Norh American Leaders from Mexico and the United States (Presidents) and Canada (Prime Minister), who are supported by their respective Ministers or Secretaries.

The Ministers or Secretaries are in turn supported by the departments and agencies that are members of NAPAHPI, and by NAPAHPI governance mechanisms. A picture describes these relationships.

On the left hand side of the picture, the NAPAHPI member organisations for each country are listed under the heading Core Sectors, as follows:

Canada:

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- Public Safety Canada

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency

- Global Affairs Canada

Mexico:

- Secretariat of Health

- Secretariat of Security and Citizen Protection

- Secretariat of Agriculture and Rural Development

- Secretariat of Foreign Affairs

United States:

- Department of Health and Human Services

- Department of Homeland Security

- Department of Agriculture

- Department of State

The middle of the picture shows the NAPAHPI governing mechanisms. At the top is the Senior Coordinating Body (SCB), which is supported by the North American Health Security Working Group (HSWG) including an HSWG Core Group. The HSWG is in turn supported by Ad Hoc Task Forces and Sub-Working Groups.

All of these groups are also supported by the Trilateral Executive Secretariat, shown on the right hand side of the picture with a supporting arrow to each of the other groups.

At the bottom of the picture there is a footnote about the Core Sectors, noting that “At their discretion, the SCB and/HSWG may invite other sectors on ad hoc basis.”

Chapter 4: Communications protocols and triggers

Routine NAPAHPI and IHR communications channels

Regular, non-emergency communications among the SCB, HSWG, and Trilateral Executive Secretariat members are the responsibility of the Trilateral Executive Secretariat.

IHR-related communications are conducted through the three countries’ IHR NFPs. Based on the need for regional situational awareness, when one of the countries notifies the WHO through their IHR NFPs of an event that may constitute a PHEIC under IHR Article 6, it simultaneously notifies the other two countries. IHR NFPs keep the Trilateral Executive Secretariat informed of any potential PHEIC notification to WHO that originated in any of the three countries, or that were reported by other countries that could be relevant to North America according to the criteria in the NAPAHPI decision-making tool. Depending on the nature of the event, when making notifications to WHO/PAHO under Articles 7-9, IHR NFPs may consider simultaneously notifying the other two NAPAHPI countries.

In addition, in the context of NAPAHPI’s cross-sectoral One Health approach and to strengthen preparedness for events that occur in animal populations but have the potential to spill over into humans and/or environment, the three countries’ delegates to the WOAH notify their counterparts in NAPAHPI countries when a known or potential zoonotic disease event is reported to WOAH.

Emergency communications

Triggers for emergency communications

During events that need immediate regional awareness and potentially regional action (i.e., all criteria in the NAPAHPI decision-making tool have been met and the threat to human/animal health is imminent, and/or if there is a health-related national security issue), a HSWG, SCB, or partner country government representative can request through their HSWG or SCB representative that an urgent message is sent via the NAPAHPI Emergency Communications Hub (the NAPAHPI Hub).

NAPAHPI hub

The NAPAHPI Hub manages rapid emergency communications. The Hub is managed by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). The United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary’s Operations Center (SOC) serves as the NAPAHPI Hub “back-up” if PHAC experiences technical difficulties.

Roles and responsibilities

- Maintain information technology (necessary IT) communication platforms to support trilateral cross-sectoral communications during emergencies. At the request of the SCB, HSWG, the Trilateral Secretariat, or other NAPAHPI stakeholder, assess, and where appropriate, communicate immediately to convene relevant members of the Governing structure. Each of the three countries is expected to have and maintain an internal coordination procedure for communications between sectors.

- PHAC is responsible for maintaining the NAPAHPI Hub and key contacts in Canada, Mexico, and the United States, as well as their respective emergency operations centers. Additionally, each sector emergency operations center is responsible for maintaining the domestic points of contact for their sector and providing feedback to the NAPAHPI Hub in the event a NAPAHPI non-routine/emergency communication is issued.

- The NAPAHPI Hub will manage a regular schedule for testing emergency communication functions including the ability to quickly gather the SCB or HSWG and appropriate subject matter experts depending on the nature of the event/threat.

Critical information requirements

The type of information that can be discussed in an emergency call should be set prior to the meeting depending on the nature and magnitude of the emergency. The goal of this rapid information sharing is to increase regional situational awareness to improve coordination and cooperation among NAPAHPI partners as needed. The list below illustrates potential areas for discussion:

- Threat/disease source, event geographical origin/location, etc.

- Epidemiological situation, known or potential impact of the event (threat assessment and medical consequence modeling)

- Any indication of intentional, accidental, or naturally occurring causes of the event or spread of a threat agent or disease

- Diagnostic capacity (human health, animal health, environment)

- Clinical intervention protocols

- Non-pharmaceutical, public health measures and assessment of their potential economic, social, and emergency management impact

- Animal health sector control measures and interventions

- Availability and access to medical countermeasures for animals and humans

- Border measures/travel restrictions

- Health system and public health and medical personnel capacities/sharing requests

- Veterinary system surge capacity

- Risk communication developments and updates

Chapter 5: Key areas for collaboration based on trilateral lessons learned from COVID-19 and other health security emergencies

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed multiple challenges in the three countries’ preparedness and response policies, capacities, and capabilities to deal with public health emergencies, particularly those caused by transboundary health security threats, and within a context of increased regional movement of people and goods.

As agreed by the North American leaders, the HSWG conducted a trilateral, cross-sectoral review of lessons learned based on the COVID-19 and other health security events during the last decade using the 2012 NAPAPI commitments as a reference framework. Similar and new themes emerged as the result of the process, which together led to observations about the governance structure, the need to delineate the mechanisms for routine and emergency communications (Chapter 2-4), and a call to enhance collaboration on key preparedness and response areas outlined below.

Animal diseases with zoonotic potential

Animal diseases with zoonotic potential represent a threat to regional human and animal health as well as food and economic security, requiring a cross-sectoral approach to be managed effectively and in a timely manner. In recent years, increased animal and human population density, prolonged and/or constant contact between humans and animals, high mobility of live animals and animal products, and rapid regional and global movement of people have increased the potential for the emergence of zoonotic diseases with pandemic potential. Although there is existing trilateral cooperation on animal health through fora like the North American Animal Health Committee,Footnote 30 or initiatives like the North American Foot-and-Mouth Disease Vaccine Bank (NAFMDVB),Footnote 31 there is a need for a stronger collaboration between the animal and human health sectors to facilitate information sharing, implement surveillance and laboratory diagnostics, share updates about control measures and analyze the potential impact on trade and travel of zoonotic diseases with pandemic potential. The risk posed by the enhanced human/animal/environment interface requires that public health programs for zoonoses can be supported, authorized, designed, and implemented in a timely, feasible, coordinated, and effective manner. Under the NAPAHPI, the three countries recognize the need to work together with international organizations, such as WHO, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO),Footnote 32 and the WOAH to develop guidance for surveillance systems, and preparedness for and response to threats.

NAPAHPI partners intend to examine participation of other government stakeholders (and as needed, non-government actors) and to strengthen cross-sectoral collaboration with a One Health approach.

Infectious diseases with pandemic potential and other threats to regional health security

Infectious diseases with pandemic potential and other threats to regional health security including other biological, chemical, radiological/nuclear materials (either naturally occurring, or accidentally or intentionally released) require a cross-sectoral preparedness and response approach across a variety of areas:

Epidemiological surveillance and laboratory diagnostics

Rapid situational awareness when a threat agent or event is detected is critical to implement measures to contain an outbreak or mitigate its consequences. Regional definition of cases, sharing of epidemiological information, contact tracing, risk assessments, and situational reports are essential for collaboration and joint action. Moreover, cross-border collaboration among the three countries is also critical to facilitate development and/or evaluation of reagents and laboratory diagnostics, vaccines, treatments, and other medical countermeasures.

NAPAHPI partners intend to review and improve data and sample sharing agreements to facilitate the rapid movement of laboratory specimens, isolates, reagents, and supplies, as well as the development of chain-of-custody protocols for the proper and safe handling of samples and reagents.

Medical countermeasures

Medical countermeasures (MCMs), including vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics, can be important resources when responding to public health emergencies. Rapid development, acquisition, and distribution as well as timely trilateral access to MCMs has proven to be one of the most challenging aspects of the regional collaboration in response to the H1N1 (2009) Influenza Pandemic and most importantly during COVID-19.

NAPAHPI partners intend to:

- Continue exploring opportunities to create and strengthen research and development programs to increase the availability of MCMs such as vaccines, other prophylaxis, therapeutics, etc. through the development of modern, innovative, resilient, and flexible manufacturing platforms in our region.

- Foster continued collaboration among regulatory agencies to share information, as legally permissible, about regulatory requirements and approaches toward approval and/or authorization of MCMs during emergencies, including participation in regional initiatives for regulatory harmonization and/or convergence.

- Share strategies, best practices, and institutional points of contacts in each country, regarding rapid research and development, the stockpiling and real time purchase and distribution of MCMs for pandemics and other health security threats, including information about planning and/or modeling assumptions and foresight and risk analysis used when determining the requirements, contents of their stockpiles, and associated infrastructure.

- Develop strategies to facilitate potential cross-border deployment and distribution of MCMs among the three countries and to WHO and/or other recipient countries.

Public health measures

The response to an emergency or an event that poses a threat to North America may require trilateral coordinated action from NAPAHPI partners through the implementation of public health measures aimed at mitigating and reducing the impact to the region. Such measures should be consistent with the IHR (2005), seek to control and, to the extent possible, stop the spread of disease or to address the negative health effects of other events as well as minimize interference with travel and trade. The public health measures implemented should be evidence-based, feasible, and adapted as the threat evolves, considering factors such as the level of disease spread at the time of detection, transmissibility, or the magnitude of the health threat and its actual or potential effects on national and regional public health, as well as their economic and social impact. To this end, rapid information sharing among the three countries is critical to properly assess risk and inform trilateral coordination efforts.

NAPAHPI partners intend to explore ways in which rapid trilateral communications could support the widespread and timely implementation of public health measures within the region.

Medical supply chains

All three countries acknowledged there was a clear disruption of medical supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. This included a lack of coordination regarding availability and access to COVID-19 vaccines (including vaccine manufacturing supplies and ancillary material), therapeutics, and other products needed for the response. During an emergency, the sharing of information among the three partners can facilitate assessments in the availability of critical supplies required for the response.

NAPAHPI partners intend to explore medical supply needs and challenges with the consideration of creating a North American Pandemic Supply Chain Network.

Health systems

COVID-19 highlighted the vulnerability of the health system infrastructure and capacity in the three countries, which suffered from medical personnel shortages, lack of hospital beds, ventilators, delayed access to personal protective equipment, basic health care materiel, workers safety protocols, surge capacity protocols, etc. Although the three countries have vastly different health systems, there is a need for a trilateral dialogue about areas where there could be better cooperation and coordination to plan for surge capacity as well as access and sustainability of resources including, for example, exploring the sharing of materiel or exchange of health care personnel. The integrity of the health system and medical care surge capacity are necessary to maintain critical services for ongoing health needs of patients or individuals to reduce mortality and morbidity, not only for the public health emergency at hand but all other health needs. Those needs include urgent surgeries or treatments, emergency department access, availability of physician’s and diagnostic services, as well as maintaining ongoing public health programs such as routine childhood immunizations.

NAPAHPI partners intend to explore areas where cooperation and coordination can be facilitated related to strengthening health system capacity (e.g., surge capacity, equipment and supplies availability and access, health care personnel availability and cross-border assistance, etc.).

Risk communications

Effective risk communications can facilitate information exchange that enables decision makers, stakeholders, and the public to make well-informed decisions during emergencies, potentially mitigating loss of life, serious illness, and social and economic disruption. Although NAPAHPI partners have shared experiences and best practices on risk communications, including on responding to “infodemic”Footnote 33 aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a need for a more systematic approach through NAPAHPI, which can serve as a helpful forum for discussing lessons learned and best practices in risk communications and to coordinate messages during a response.

NAPAHPI partners intend to explore best practices to address the “infodemic” phenomenon and improve risk communications.

Border health measures

The implementation of border health measures at airports, seaports, and land borders such as screening of passengers, vaccination requirements, quarantine, and entry restrictions, etc., should be evidence-based and aimed to slow the introduction or spread of a pathogen in the region; to allow sufficient time for the health and public health system to develop surge capacity; to allow for the movement of people, live animals, and goods to mitigate impacts to the economy and the functioning of our societies; and to facilitate the cross-border flow of medical equipment, materials, samples and reagents to assist the three countries and potentially other countries.

These measures should be implemented in alignment with other public health measures, following IHR guidance, and under applicable law in each country. COVID-19 showed that a high-level policy trilateral discussion could have allowed for a more coordinated regional implementation of border measures potentially maximizing their impact and minimizing unnecessary interference with international (or regional) traffic and trade.

NAPAHPI partners intend to explore the feasibility of conducting an analysis and evidence review of the effectiveness of international border measures/closures during COVID-19 to inform future responses.

Critical infrastructure

Critical infrastructure refers to the assets, systems and networks that are essential to the security, public health and safety, economic vitality, and way of life of citizens. Critical infrastructure disruptions can result in catastrophic losses, including human casualties, property destruction, economic effects, damage to public morale and confidence, and impacts on nationally critical missions. Risks are heightened by the complex system of interdependencies among critical infrastructure, which can produce cascading effects far beyond the initially impacted sector and physical location of the incident. Moreover, critical infrastructure is not only interconnected across sectors, but also beyond borders. For this reason, the impacts of a disruption can rapidly escalate within a country and may cause significant consequences from both a cross-sector and cross-border perspective. In a pandemic or a public health emergency, understanding the risks and interdependencies is fundamental to providing a coordinated cross-sector response.

Canada, Mexico, and the United States share interdependencies among several industries including travel, tourism, transportation, and commercial facilities sectors. The COVID-19 pandemic confirmed the importance of harmonization and joint consideration among all three countries on critical infrastructure to encourage the promotion of business continuity planning and contingency plans for all degrees of event severity. Moreover, all three NAPAHPI countries recognize that private sector entities play key and interdependent roles in sustaining critical services, delivering essential commodities, and supporting public health recommendations. Trilateral action should seek to improve resilience both at the country level and across our borders.

To reduce the negative effects of a health security threat to North American critical infrastructure and other important sectors, the three countries may coordinate throughout the event, support each other, and assist to improve resiliency during the event. Joint action can include identifying key actors (government and non-government) and assets, mapping critical infrastructure in the three countries and interdependencies among them, improving information sharing, conducting simulation exercises, and participating in public and private sector critical infrastructure partnerships.

NAPAHPI partners intend to conduct an environmental scan of critical infrastructure stakeholders and assets, and to determine interdependencies among health and other critical infrastructure sectors, to guide a set of exercise scenarios and potential collaborative actions/contingencies to protect them during emergencies.

Risk assessment and foresight risk analyses

Effective use of modeling and data analysis can improve risk analysis, strengthen prevention, and control capabilities, and enable timely and effective decision-making during a response. The three countries could leverage existing or develop and share new tools for modeling and risk assessment to enhance trilateral capacity for foresight risk analysis related to infectious diseases with pandemic potential and other health security threats.

NAPAHPI partners intend to consider hosting designated meetings to explore modeling, risk assessment, and foresight risk analysis tools.

Joint exercises and training

Joint exercises, conducted either bilaterally or trilaterally and including the participation of all relevant sectors, can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of existing emergency response and contingency plans, identify opportunities to strengthen those plans, and implement improvements, including through the design and delivery of trainings. There is a need for Canada, Mexico, and the United States to enhance the interface among their respective emergency management/response structures through joint training and exercises conducted through scenario-based, facilitated discussions, workshops, table-top exercises, and/or full-scale drills as needed.

NAPAHPI partners intend to:

- Conduct trilateral and/or bilateral exercises and training to assess and strengthen emergency response and contingency plans.

- Share post-event "lessons learned" to inform future exercises and training activities.

Sustainable financing

Adequate and sustainable financing to support preparedness for and response to pandemics and other public health emergencies is critical to achieve health security at the national, regional, and global levels. This facilitates the development, strengthening, and maintenance of capacities and capabilities to prevent, detect, and respond to broad set of health security threats. As various health security-relevant financing instruments and initiatives are considered at the regional and global levels, there is a need for a trilateral forum for the three countries to discuss their positions regarding access and/or contributions to these financial instruments and initiatives.

NAPAHPI partners intend to consider analyzing access and/or contributions to global and regional financial instruments for preparedness and response to gain visibility and, to the extent possible, coordinate positions that benefit the region.

Annex: Acronym list

- AI

- Avian influenza

- CFIA

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency

- DHS

- Department of Homeland Security (United States)

- DOD

- Department of Defense (United States)

- DOS

- Department of State (United States)

- DOT

- Department of Transportation (United States)

- EOC

- Emergency operations center

- FAO

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- HHS

- Department of Health and Human Services (United States)

- HPAI

- Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza

- HSWG

- Health Security Working Group

- IT

- Information Technology

- IHR

- International Health Regulations

- MCMs

- Medical Countermeasures

- NALS

- North American Leaders Summit

- NAPAPI

- North American Plan for Animal and Pandemic Influenza

- NAPAHPI

- North American Preparedness for Animal and Human Pandemics Initiative

- IHR NFP

- National IHR Focal Point

- PAHO

- Pan American Health Organization

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PHEIC

- Public Health Emergency of International Concern

- PS

- Public Safety Canada

- SADER

- Secretariat of Agriculture and Rural Development (Mexico)

- SCB

- Senior Coordinating Body

- SSCP

- Secretary of Security and Citizen Protection (Mexico)

- SPP

- Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America

- SRE

- Secretariat of Foreign Affairs (Mexico)

- SALUD

- Secretariat of Health (Mexico)

- USDA

- United States Department of Agriculture

- WOAH

- World Organization for Animal Health

- WHO

- World Health Organization

References

- Reference 1

-

For the purpose of this document, “region/regional” refers to Canada, Mexico, and United States in North America

- Reference 2

-

For the purpose of this document, “North American leaders” refer to the Prime Minister of Canada, and the Presidents of Mexico and the United States

- Reference 3

-

https://www.iatp.org/documents/north-american-plan-for-avian-pandemic-influenza-0

- Reference 4

-

https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/international/Documents/napapi.pdf

- Reference 5

-

https://www.pm.gc.ca/en/news/backgrounders/2021/11/18/joint-statement-north-american-leaders

- Reference 6

-

https://www.gob.mx/presidencia/prensa/declaration-of-north-america-dna-323453?idiom=es

- Reference 7

-

https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/one-health

- Reference 8

-

https://www.iatp.org/documents/north-american-plan-for-avian-pandemic-influenza-0

- Reference 9

-

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2009/08/10/north-american-leaders-summit

- Reference 10

-

https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/international/Documents/napapi.pdf

- Reference 11

-

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2012/04/02/joint-statement-north-american-leaders

- Reference 12

-

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi/2r9852000002aa8v-att/2r9852000002aags.pdf

- Reference 13

-

https://www.pm.gc.ca/en/news/backgrounders/2021/11/18/joint-statement-north-american-leaders

- Reference 14

-

https://www.gob.mx/presidencia/prensa/declaration-of-north-america-dna-323453?idiom=es

- Reference 15

-

https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/one-health

- Reference 16

-

https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern-(pheic)-global-research-and-innovation-forum

- Reference 17

-

https://www.woah.org/en/home/

- Reference 18

-

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health.html

- Reference 19

-

https://inspection.canada.ca/

- Reference 20

-

https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca

- Reference 21

-

https://www.international.gc.ca/

- Reference 22

-

https://www.gob.mx/salud

- Reference 23

-

https://www.gob.mx/agricultura

- Reference 24

-

https://www.gob.mx/sre

- Reference 25

-

https://www.gob.mx/sspc

- Reference 26

-

https://www.hhs.gov/

- Reference 27

-

https://www.dhs.gov/

- Reference 28

-

https://www.usda.gov/

- Reference 29

-

https://www.state.gov/

- Reference 30

-

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/newsroom/stakeholder-info/SA_By_Date/2019/SA-08/afs-joint-statement

- Reference 31

-

https://uia.org/s/or/en/1100003615

- Reference 32

-

https://www.fao.org/home

- Reference 33

-

https://www.who.int/health-topics/infodemic

Page details

- Date modified: