The time is now - Chief Public Health Officer spotlight on eliminating tuberculosis in Canada

Download the entire report

(PDF format, 842 KB, 26 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Type: Report

Date published: 2018-03-22

A Message from Canada's Chief Public Health Officer

Tuberculosis (TB) is the epitome of inequity in public health; it is a social disease with a medical aspect.

As this report makes clear, social determinants of health such as poverty, food insecurity, inadequate housing and overcrowding contribute to health inequity and are significant underlying risk factors for TB.

While Canada has come a long way toward reaching TB elimination with the advent of antibiotics and overall improvement in socio-economic conditions, progress has plateaued since the 1980s.

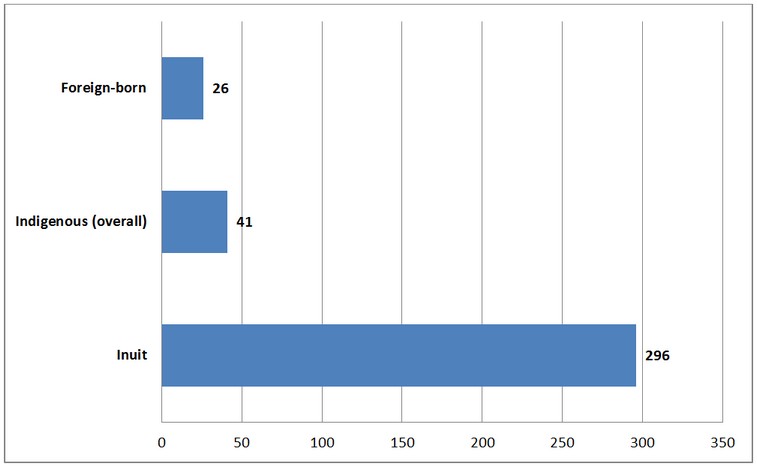

My decision to shine a spotlight on TB with this report is largely inspired by the current momentum to eliminate TB coming from the force of leadership within Inuit communities. TB rates are almost 300 times higher among Inuit than for the Canadian born non-Indigenous population. These unacceptably high rates reflect the Inuit's unique experience with TB, a long history of social inequities, and the ongoing impacts of colonization.

In addition, about 70 percent of cases of active TB disease in Canada are diagnosed in people who were born outside the country. Adult refugees from locations with a high incidence of the disease who have latent TB infection (LTBI) are at the highest risk of developing active TB disease. With enhanced knowledge of the predictors of active TB disease in people migrating to Canada, we will be able to understand their unique experiences with TB and better tailor interventions and supports.

There is no better time than now to accelerate our efforts to eliminate this treatable and curable disease. Improved rapid diagnostics for active TB disease are now available, allowing for timely treatment and reducing transmission. Reactivation of the disease from untreated LTBI remains a major source of new active TB disease and transmission. Better tests and approaches to identify those individuals at the highest risk for disease reactivation, combined with more timely and effective LTBI treatment plans, all offer great promise.

The key to achieving TB elimination in Canada lies in reducing the disproportionate impact of the disease on Indigenous peoples, in particular Inuit, and foreign-born individuals. This can only be achieved through collaborative action.

Ultimately, the solutions to this complex social disease will be driven by the communities themselves, with sustained support from many players, including governments, academics, experts and other stakeholders. Efforts that address social inequities coupled with improved diagnosis and treatment of active TB disease and LTBI will level the playing field and help eliminate TB in all of Canada.

Acknowledgements

Many individuals and organizations have contributed to the development of my Chief Public Health Officer (CPHO) Spotlight on Eliminating Tuberculosis in Canada.

I would like to express my appreciation to everyone who provided invaluable expert advice, including Dr. Jeff Reading from the University of Victoria. A special thank you goes out to Dr. Gonzalo Alvarez, from the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, for sharing his expertise and reviewing many drafts.

In addition, I would also like to recognize the contributions made by partners and stakeholders who were consulted, including staff from Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Marlene Laroque and Tammy Cote from the Assembly of First Nations, Wenda Watteyne from Métis National Council, Dr. Elizabeth Rea from Toronto Public Health, Dr. Tom Wong from Indigenous Services Canada, as well as Dr. Dominique Elien Massenat and Michael Mackinnon from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

I would also like to sincerely thank the many individuals and groups within the Public Health Agency of Canada and Health Canada for all of their efforts related to the development of this report, including Dr. Howard Njoo, Marc-Andre Gaudreau, Katherine Dinner, Linda Lord, Dr. Winnie Siu, Julie Vachon, Nashira Khalil, Dr. Chris Archibald, Cindi Corbett, Jeannette Macey, Donna Malone, Maxime Pedneault, Stéphanie Parisien, Andrea Raper, Kerry Robinson, Kelly Folz, and Pierre Desmarais.

I appreciate the excellence and dedication of members of my CPHO Reports Unit in researching, consulting on and developing this report: Lori Engler-Todd, Larry Shaver, Aimée Campeau, Dr. Hong-Xing Wu, Gerri-Lynn Dolan, Fatimah Elbarrani, and Rhonda Fraser.

TB in Canada today

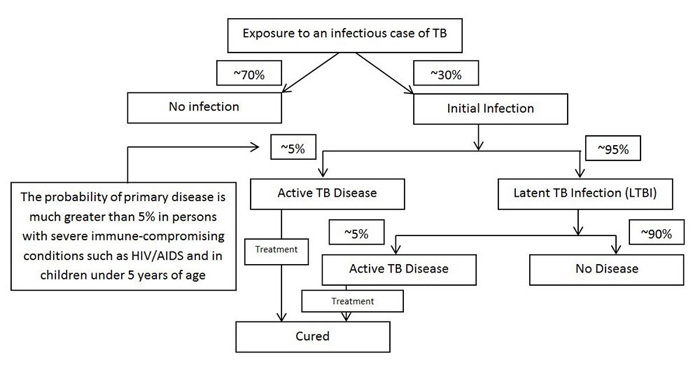

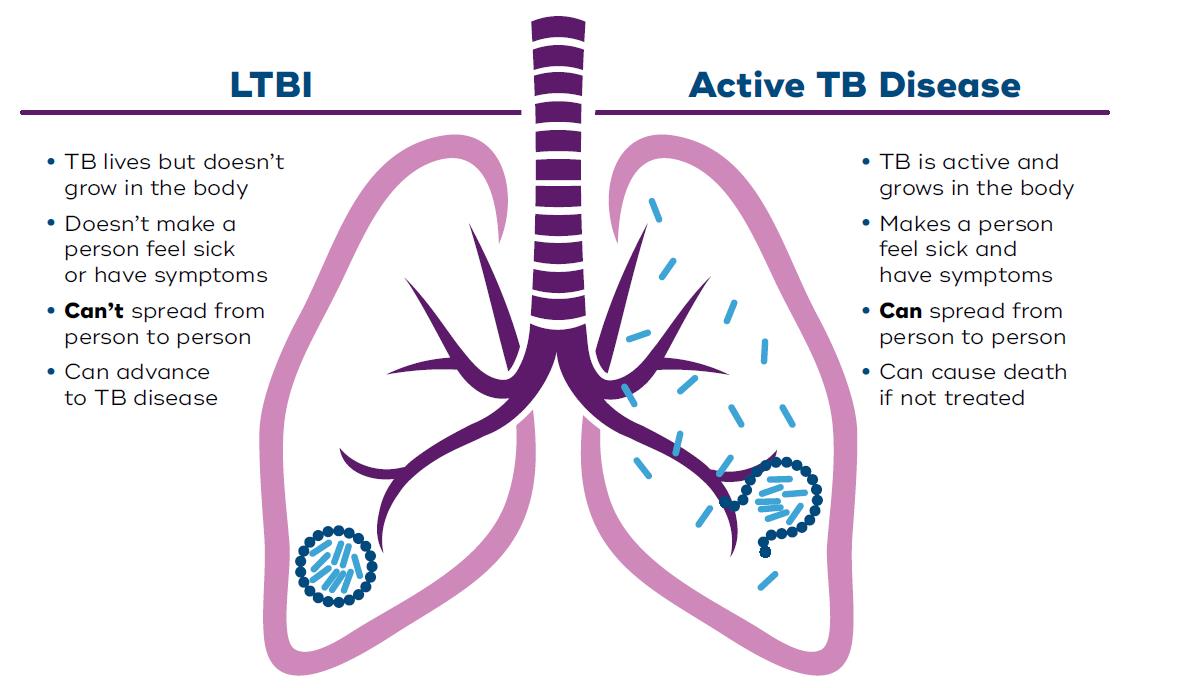

What is tuberculosis (TB)? TB is a serious but treatable and curable infectious disease. It is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis and is spread through the air after prolonged contact with an infectious person through coughing, sneezing and talking.Footnote 1 After breathing in the TB bacteria, most people's immune systems are able to fight off an infection or "contain" the bacteria, which prevents or delays the onset of the illness (see Figure 1). This is called latent TB infection (LTBI) (see Image 1). A person with LTBI is not sick and is not contagious.Footnote 1 However, after initial infection, about one in ten people in Canada will develop active TB disease over time, often within the first two years of becoming infected.Footnote 2

TB primarily infects the lungs but can also affect other parts of the body, including the kidneys, spine and brain.Footnote 1 Symptoms of active TB disease can vary but typically include a cough that lasts two weeks or longer, coughing up blood, chest pain, weakness or tiredness, weight loss, and chills and fever, among other signs.

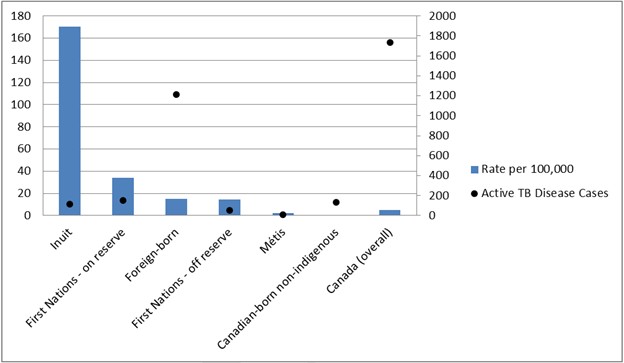

While overall rates of TB are currently low in Canada, the global burden of the disease remains high. TB is the leading cause of death worldwide from an infectious disease with just over 10 million people diagnosed with the active form of the disease, causing close to 1.7 million deaths in 2016.Footnote 3 Canada has the second lowest incidence of all G7 countries after the United States.Footnote 4 The latest data show that there were over 1,700 people diagnosed with active TB disease in Canada in 2016, resulting in a rate of just under 5 cases per 100,000 (see Figure 2).Footnote 4

Sources: adapted from the Public Health Agency of Canada. (2014). Canadian Tuberculosis Standards, 7th Edition; and Shaler, C. R., Horvath, C., Lai, R., & Xing, Z. (2012). Understanding delayed T-cell priming, lung recruitment, and airway luminal T-cell responses in host defense against pulmonary tuberculosis. Clinical and Developmental Immunology, 2012.

Figure 1 - Text description

This figure describes potential outcomes for the infected host once exposed to the TB bacteria

After exposure to the TB bacteria, approximately 30% will develop an initial infection. The remaining 70% of people will not go on to develop an infection. Approximately 5% of persons who become infected with M. tuberculosis will develop active TB disease relatively soon afterward. The probability of developing active TB disease is much greater in those with severe immune-compromising conditions such as HIV/AIDS, and children under 5. Those who do not develop active TB disease will have latent TB infection (LTBI). A small proportion of persons with LTBI, a balance of about 5% of those infected, will later develop active TB disease. Approximately 90% of persons infected with M. tuberculosis; who do not have immune-compromising conditions such as HIV/AIDS, will never develop TB disease. Active TB disease is curable with treatment.

Tremendous gains have been made in the prevention and control of TB in Canada since the 1940s and 1950s when the country's overall rates were high and many people died of the disease.Footnote 5 The development of antibiotics, notably streptomycin, in the 1940s along with social and infrastructure improvements that reduced the likelihood of person to person transmission of TB radically reduced the impact of this infection on the health of many Canadians.Footnote 5

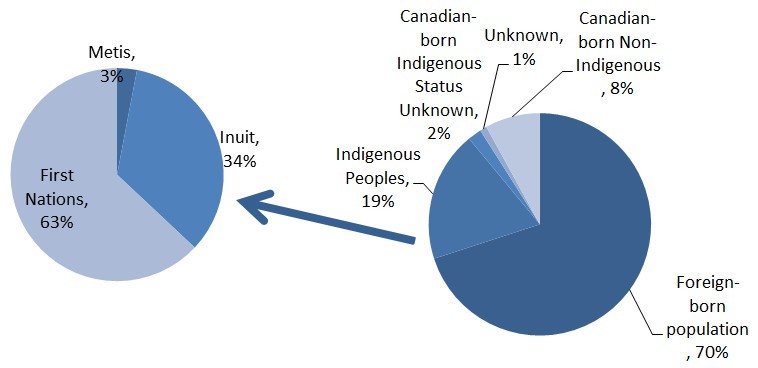

Despite these important gains, those that remain disproportionately affected by active TB disease in Canada are First Nations on-reserve, Inuit and foreign-born individuals in Canada,Footnote 4,Footnote 6 particularly refugees, from countries with a high incidence of TB.Footnote 2,Footnote 4,Footnote 7 These populations are the focus of this report. Canadian-born, non-Indigenous people make up a small proportion of active TB cases (see Figure 3).Footnote 4

Source: adapted from Kanabus, A. (2017). Information about Tuberculosis. Global Health Education.

Image 1 - Text description

Latent TB Infection

- TB lives but doesn't grow in the body

- Doesn't make a person feel sick or have symptoms

- Can't spread from person to person

- Can advance to active TB disease

Active TB Disease

- TB is active and grows in the body

- Makes a person feel sick and have symptoms

- Can spread person to person

- Can cause death if not treated

Others also at risk of becoming infected with TB bacteria and developing active TB disease include the homeless, injection drug users, residents of correctional facilities or long-term care facilities, health care workers and those with an impaired immune system.Footnote 2

First Nations, Inuit and Métis

The TB epidemic was brought to Canada by Europeans in the 18th century and then dispersed among the population.Footnote 8 The sustained impact of colonialism still contributes to the high rates of TB we see today in the Northern First Nations and Inuit communities.Footnote 9 With colonization came the removal of First Nations from their lands and territories and the forced relocation of Inuit to government-determined settlement areas across Inuit Nunangat. The establishment of the reserve system, followed by the residential schools era, aggravated the impact of TB through over-crowding, poor nutrition, and inadequate sanitation.

The CD Howe: In the 1940s ships such as the CD Howe or "hospital boats" were used in the Eastern Arctic Patrol to test and evacuate Inuit with TB.Footnote 13 If found ill, the letters "TB" were printed on the patient's hand and they were transported to provincial hospitals in the South and sanatoria for treatment sometimes only hours after diagnosis.Footnote 13The forcible removal of people (even children and infants) from their families and loved ones resulted in great emotional distress and, in some cases, hindered the survival of those at home.Footnote 13

Many First Nations, Inuit and Métis children died from TB while attending residential schools.Footnote 10 In the 1930s and 1940s TB mortality rates exceeded 8,000 per 100,000 among children confined to residential schools and 700 deaths per 100,000 among adult First Nations people living on reserve.Footnote 9 These mortality rates from TB are among the highest ever recorded in the world.Footnote 9

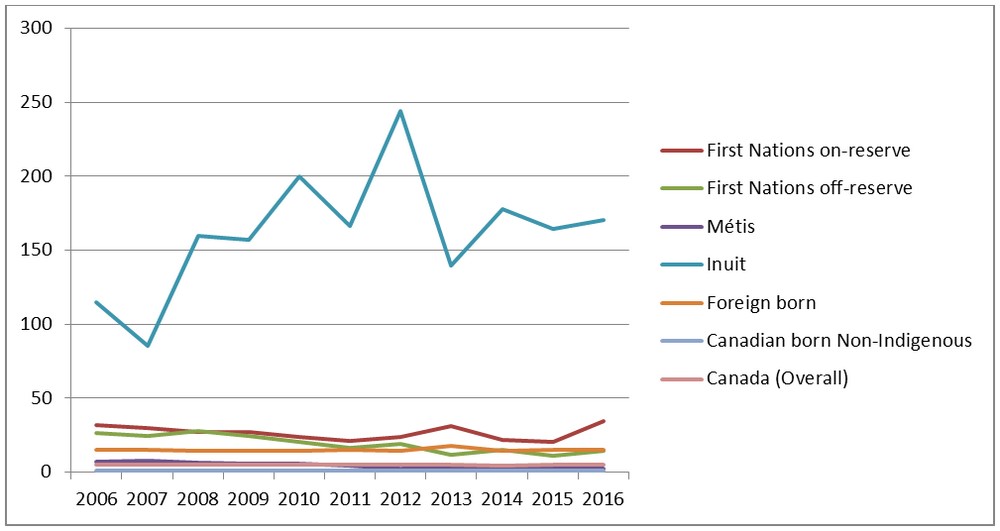

In 2016, First Nations, Inuit and Métis made up just under 5% of the total Canadian population, but accounted for almost 20% of reported cases of active TB disease.Footnote 4 Rates vary across Indigenous populations, for instance, the rate of TB among Inuit was almost 300 times higher than the rate in the Canadian-born, non-Indigenous population in 2016 (see Figure 4).Footnote 4 However, while little progress has been made since the 1980s, the incidence rate among First Nations living off-reserve, as well as among the Métis, has started to decrease over the past decade (see Figure 5).Footnote 4

It is clear that more needs to be done to reduce the serious impact TB is having on First Nations living on-reserve and Inuit.

Foreign-born populations

Canada has rigorous medical requirements for immigration prior to entry. Before entering Canada, all individuals applying for permanent residency, and certain individuals applying for temporary residency, undergo an immigration medical examination which includes a chest x-ray for applicants 11 years of age and older to detect active TB disease.Footnote 2 This process is in place to ensure that those with active TB disease, which is contagious, are treated prior to their arrival in order to minimise the risk of passing it on to someone else.Footnote 2

Yet, due to the nature of the disease, foreign-born populations with LTBI can become ill with active TB disease, months or years after the migration process. Because of this risk, individuals arriving in Canada report to local public health authorities for further follow-up if there was evidence of previous active TB disease. As previously noted, LTBI is not contagious and most people with LTBI do not become sick with active TB disease. Additionally, migrants to Canada can become infected with TB bacteria during return travel to their country of origin.Footnote 2 It is important to note that anyone, born in Canada or elsewhere, who spends enough time in a country with high TB incidence can also become infected with TB.Footnote 11

In 2016, the foreign-born population, representing approximately 22% of the total Canadian populationFootnote 12, accounted for 70% of reported new or re-treatment cases of active TB disease for a rate of 15 cases per 100,000.Footnote 4

Source: Vachon, J., Gallant, V., Siu, W. (2018). Tuberculosis in Canada, 2016. Canada Communicable Disease Report, 44(3/4), 75-81.

Figure 3 - Text description

| Indigenous Sub-population | Percent of cases |

|---|---|

| Metis | 3% |

| Inuit | 34% |

| First Nations | 63% |

| Sub-population | Percent of cases |

|---|---|

| Foreign-born population | 70% |

| Indigenous Peoples | 19% |

| Canadian-born Indigenous Status Unknown | 2% |

| Unknown | 1% |

| Canadian-born Non-Indigenous | 8% |

Factors that influence disease

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines social determinants of health as the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age.Footnote 30

A variety of personal risk factors and the social determinants of health come into play for TB infection and disease development. Because it attacks the immune system, the most important risk factor for the development of active TB disease for a person with LTBI is HIV infection.Footnote 14 Other personal risk factors that reduce the ability of the body's immune system to fight off a TB infection include: smoking tobacco, alcohol and substance use, as well as diabetes and medications that impair the immune system.Footnote 14,Footnote 15 Public health messages such as "if you puff, don't pass" are used to educate about the risks of becoming infected with TB during shared use of tobacco and cannabis smoking devices.Footnote 16

Poverty is a recognized social determinant of health. It enables vulnerabilities that expose people to simultaneous risk factors for TB, including crowded housing and malnutrition.Footnote 14

Health equity means that all people can reach their full health potential and should not be disadvantaged from attaining it because of their race, ethnicity, religion, gender, age, social class, socioeconomic status, geography or other socially determined circumstance. Footnote 31

In addition, barriers to timely health care, including delays from diagnosis to treatmentFootnote 14 and a lack of culturally competent health care can negatively impact TB outcomes.Footnote 17 Delays in diagnosis and treatment increase the risk of consequences to the person, including death, and increase likelihood that the TB bacteria will be transmitted to others. Fear of being discriminated against due to having an infectious disease, or stigma, can be a significant contributing factor to delays in diagnosing TB.Footnote 18 Some people with TB are subject to multiple types of stigma and discrimination at the same time, such as based on ethnicity, or living in poverty, or living with a mental illness.

First Nations, Inuit and Métis

"If we start with this idea that we can eliminate TB in Inuit Nunangat, then I hope that other things will follow because you can't look at this issue…without thinking that we need to do something about overcrowding or social conditions." Footnote 32

Natan Obed

President of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami

Due to the ongoing effects of colonization, First Nations, Inuit and Métis experience distinct determinants of health which affect susceptibility to TB including inadequate housing and community isolation.Footnote 19,Footnote 20 Some factors that contribute to high rates of active TB disease among these groups include:

Inadequate housing conditions can affect risk for TB infection and outcomes as a result of poor ventilation and air quality in the home.Footnote 15,Footnote 21 For instance, almost half of Inuit live in houses they cannot afford, require major repair, or which are not sufficiently large.Footnote 22

Related to the above, overcrowding can also increase the risk of TB transmission. Approximately one-quarter of First Nations adults live in over-crowded housingFootnote 23 that lack basic amenities.Footnote 19

"…there is a TB crisis in Nunavut at this very moment. There are fourteen out of the twenty-five disparate communities wrestling with active and latent cases, many of them children. The numbers are small (compared to a place like India, they're infinitesimal), but they loom very large in a population of roughly thirty-five thousand…The active cases are in treatment. It's prodigiously difficult to maintain and oversee the regimen. But treatment works. As you know, TB is a hundred per cent curable."Footnote 60

Stephen Lewis

Philanthropist

Food insecurity - the state of being without reliable access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food - can lead to hunger and malnutrition. A study in Nunavik has shown that inadequate nutrition is associated with increased susceptibility to LTBI.Footnote 24Nearly one quarter of Inuit have reported experiencing food insecurity.Footnote 22 This is largely linked to food shortages due to harsh climate, as well as not having enough money given the expensive retail food options.Footnote 25

Access to health care can be a barrier to treatment. First Nations patients can experience delays in the diagnosis and treatment of active TB disease when they are great distances from medical facilities.Footnote 15 In addition, Inuit who live in remote and isolated communities face unique challenges to accessing appropriate health care services. For example, they are often treated by health care workers from the South who may never have seen a case of TB.Footnote 26 In addition, health care workers are often unfamiliar with the language and culture, which makes providing care more challenging.Footnote 26

Foreign-born populations

The conditions before and after immigrating to Canada can pose physical, mental and social challenges. Moving to a new country demands a lot of change in a short time period including leaving friends and family behind, learning a new language, and the stresses of integrating into a new society. Although observations show that many migrants benefit from what is called the "healthy immigrant effect" and can have better overall health than the Canadian born, these risk factors can have a significant impact on the likelihood of foreign-born individuals developing active TB.

A recent Canadian study following over a million people who became permanent residents of British Columbia between 1985 and 2012 found that active TB was diagnosed at a rate of about 24 per 100,000 people. Refugee immigration class and higher TB incidence in the country of birth were among factors that were strong predictors of TB incidence.Footnote 7

Availability of health care services before migration, which can be impacted due to experiences with disasters or conflicts, can contribute to the overall health of migrants prior to their arrival in Canada.Footnote 17When immigrating to Canada, foreign-born persons such as refugees can sometimes experience travelling for prolonged periods, and/or under unsafe conditions, which can contribute to overall poor health and susceptibility to TB.Footnote 17,Footnote 27

Once in Canada, stressful living conditions in the years following immigration can contribute to the reactivation of active TB disease.Footnote 27 Further, language and cultural barriers can become reasons for delaying diagnosis and completing treatment.Footnote 17,Footnote 18,Footnote 28 Limited knowledge of the availability of services, what causes TB, and its symptoms as well as misconceptions of TB can lead to a delay in seeking health-care.Footnote 17,Footnote 29

Specific migrant communities may distrust public services which may delay health care seeking. For instance, undocumented migrants may fear encounters with police, or legal authorities, which can be a major deterrent to seeking health care.Footnote 17

A higher proportion of recent immigrants face food insecurity and housing issues when compared with the general Canadian population,Footnote 22 and this can impact their health. For many migrants, their food and housing situation improves after 10 years.Footnote 22

"The cultural connotations of TB for immigrant populations, and for anyone, are important. Sometimes people may associate TB with death or the old sanatoria and may avoid diagnosis or treatment."Footnote 33

Elizabeth Rea

Associate Medical Officer of Health,

Tuberculosis Prevention and Control,

Toronto Public Health

TB Elimination

Globally, about two billion people out of the world's population of eight billion are estimated to be infected with LTBI.Footnote 34 The target of the World Health Organization's (WHO) "End TB Strategy" is to reduce the global incidence to ten cases per 100,000 or less by 2035.Footnote 3 Canada is committed to meeting the WHO goal of reaching less than one TB case per 100,000 by 2035.Footnote 35

Relying on medical interventions alone will not be enough to eliminate TB. As Sir Michael Marmot notes, "why treat people and send them back to the conditions that made them sick?".Footnote 35 That cycle needs to be broken.

The low rate in the Canadian-born non-Indigenous population of 0.6 cases per 100,000 is proof of the concept that TB can be eliminated in all populations in Canada.Footnote 4 Achieving this will require coordinated action by many partners on several fronts, including:

- The social determinants of health and health inequities;

- Awareness and education;

- Medical advancements;

- Community-led TB initiatives;

- Global TB elimination efforts.

The social determinants of health and health inequities

Efforts that improve living conditions and address poverty will generate health benefits well beyond TB. To help address health inequity, investments are being made to improve the living conditions for Indigenous Canadians.Footnote 37

For example, housing improvements are a priority. The Assembly of First Nations and the Chiefs Committee on Housing and Infrastructure are jointly driving development of a First Nations National Housing and Infrastructure Strategy, which will include housing both on- and off-reserve.Footnote 38 At the same time, all partners and stakeholders in First Nations health are collaborating towards development of a 10-year First Nations Housing Strategy aimed at supporting housing on reserve.Footnote 37 In addition, resources have been committed for an Inuit-led housing plan in the Nunavik, Nunatsiavut, and Inuvialuit regions, which supplements funding provided for housing in Nunavut in 2017.Footnote 39 The Inuit Crown Partnership Committee (ICPC) was created as a joint effort between the Government of Canada and Inuit elected officials to advance shared priorities, such as an Inuit Housing Strategy that will better meet the housing needs of the population.Footnote 40

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015) report outlines the actions necessary to redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of reconciliation.Footnote 10The underlying historical context of intergenerational trauma and cumulative disadvantage as experienced by Indigenous populations must be addressed by and for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis. The work outlined by the Nanilavut Initiative in the North is an example of an Inuit led solution.Footnote 40

The World Health Organization has classified tuberculosis as a disease of poverty.Footnote 61

The key risk factor for TB in foreign-born populations is coming from a country with high rates of TB, which can be heightened for those coming from an impoverished country with inadequate health systems to diagnose and treat the disease. While most foreign-born Canadians are economic migrants who enjoy a high standard of life, a subset, including refugees, come from challenging living conditions and may also encounter relative poverty after they settle in Canada at least for a period of time.Footnote 22More research can shed light on the socioeconomic status of the foreign-born populations who are most affected with TB to support more targeted programming.Footnote 27

Awareness and education

Stigma, or being made to feel shame because of an illness, can be a barrier to screening and treatment as many people may fear that a diagnosis of TB could affect their relationships with friends, families, or communities. More research on stigma in low incidence countries could offer innovative opportunities to conduct TB elimination programs in a way that does not inadvertently reinforce stigmatization.Footnote 41

Education and awareness for healthcare providers serving First Nations and Inuit communities is an essential component to eliminating TB. One example is a 2016 community mobilization project in Kangiqsualujjuaq, Nunavik, which aimed to increase TB awareness among Inuit.Footnote 40Community involvement in prevention activities, and a high level of trust between health care providers and community members, was essential to the project's success.

"The great thing about TAIMA TB is it showed us a new way."

Natan Obed

President of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami Footnote 62

Engagement and empowerment of Indigenous leaders, health professionals and community members is an equally important component (see Image 2). For example, TAIMA TB is a group of research projects supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Government of Nunavut, the Public Health Agency of Canada, and the Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI) in collaboration with the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Aimed at helping Inuit in Canada stop the transmission of TB in their communities, the partnership is based on principles of collaboration, education, innovation, and evaluation. One of the projects involves raising community awareness about TB followed by a door-to-door screening campaign in Iqaluit. It is expected this campaign will contribute to successful control of TB in targeted communities and highlights the strength of Indigenous participatory research. To date, the campaign has led to more people getting screened and to a level of LTBI detection in high-risk residential areas that may not have been achieved through existing public health efforts.Footnote 42

Various provincial and federal organizations, such as the First Nations Health Authority (BC) and the Northern Inter Tribal Health Authority (SK), have developed programs to address TB through enhanced screening and raising awareness of TB, and engaging on-reserve First Nations communities.

It is important to clear up misconceptions that can lead to stigma by enhancing awareness and education on TB in addition to screening and treatment for LTBI and active TB disease.Footnote 43,Footnote 44Furthermore, culturally competent care, provided by health care workers and families, increases treatment completion within foreign-born populations.Footnote 44Building partnerships and community engagement to develop awareness and appropriate messaging may also be effective. A photovoice project called "Toronto unites to end TB" allows those with active TB disease, primarily Canadian newcomers, to overcome stigma by reflecting on their experiences.Footnote 45

In 2016, a logo contest was held in Nunatsiavut as part of TB awareness campaign where they experienced an outbreak of TB that most targeted youth. The winning logo (shown) was developed by Vanessa Flowers for the community of Hopedale.

Source: Nunatsiavut Government. (2017). Winners announced for TB and sexual health and wellness logo contests.

Image 2 - Text description

This logo depicts an inuksuk structure supported by two lungs.

Our Land, Our Air,

TB Free Together

Nunagijavut, Ikkiavut,

TB puvallungimagilluta katingaluta

Medical advancements

While there is a vaccine for TB called the bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine, it has limited effectiveness, and is not recommended for routine use. However, it is still being used in regions of Canada where TB rates remain high, given that it does reduce the severity of the disease in children. Globally, the WHO/UNICEF estimated that in 2007, 89% of the global population were immunized with the BCG vaccine before the age of one.Footnote 46Efforts are ongoing to develop a more effective vaccine that would help greatly to eliminate TB in Canada and internationally.Footnote 46,Footnote 47

TB can be cured. Treatment for active TB disease typically involves taking treatment for six months with multiple antibiotics. The current standard for the treatment of LTBI is nine months of one antibiotic (isoniazid). Ongoing investment in TB drug research is needed to identify shorter, less toxic and more effective treatment regiments. A new treatment regime with a much shorter course for LTBI known as 3HP, a combination therapy of rifapentine and isoniazid, is as effective as the current standard treatment.Footnote 48Currently an implementation study is underway in Ottawa and Iqaluit to determine if this shorter course of treatment will result in higher completion rates when compared to the standard treatment.Footnote 49 Rifapentine was recently placed on the List of Drugs for an Urgent Public Health Need in order to assist current TB elimination efforts. Health Canada will now allow its importation into Canadian jurisdictions that have notified the department of an urgent public health need.Footnote 50

Rapid diagnosis and treatment to reduce transmission of the disease to others is essential to TB elimination. With recent introduction of the GeneXpert® automated diagnostic test in Iqaluit, Nunavut, the time between diagnosis and treatment of active TB disease has been significantly shortened by avoiding the need to send samples away for testing.Footnote 51

Key in the quest for TB elimination is to prevent LTBI from developing into active TB disease in high risk groups. Research has demonstrated that interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) for LTBI screening, as opposed to the Tuberculin Skin Test (TST), may offer a more specific method to detect LTBI in those that have been previously vaccinated with BCG.Footnote 52This is particularly relevant in certain Indigenous communities and foreign populations who are more likely to have been vaccinated with BCG.

Community-led TB initiatives

Ultimately, efforts to control TB will be more successful when the communities affected by TB in Canada are fully engaged, with the support of partners. In 2013, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), the national representative organization for Canadian Inuit, published the Inuit-specific TB Strategy to outline a path forward for reducing the disproportionately high burden of TB disease across the Inuit homeland (Inuit Nunangat) (see Image 3). The Strategy takes a community partnership perspective, and proposes implementation of innovative screening and treatment approaches in combination with addressing social determinants of Inuit health to lessen the burden of TB disease among the population.Footnote 53Furthermore, new investments have been dedicated over the next five years to supporting the elimination of TB across Inuit Nunangat.Footnote 39To help achieve this, the ITK is working with the Inuit TB Elimination Task Force to develop an elimination framework.

In 2016, Nunatsiavut experienced an outbreak of active TB disease with the majority of cases affecting young males. Boas Mitsuk is an Inuit youth champion dedicated to debunking the stigma and fear that still exists today related to TB in northern Inuit communities and the sanatoria of the past. He is raising awareness of the challenges associated with TB treatment and follow-up.

Global TB elimination efforts

Controlling TB in high incidence countries contributes to reducing TB transmission globally. This may also offer better returns on investment than screening and treating TB domestically.Footnote 54,Footnote 55Canada currently contributes to international programs that fund TB elimination programs, and has committed funding to Stop TB Partnership's TB REACH initiative.Footnote 56Canada is linked to the global infectious disease burden. This includes global TB antibiotic resistance, which is currently rare in Canada.Footnote 57Inadequate or interrupted treatment can contribute to antibiotic resistant strains of TB bacteria which can make the disease difficult or impossible to treat.Footnote 58This emerging global trend may be further complicated by factors such as poverty, stigmatization and absence of community engagement.Footnote 58

A more targeted, pre-arrival screening program, focusing on high risk individuals from countries with a high incidence of TB, may offer a more cost-effective approach for TB screening in migrants.Footnote 7,Footnote 59 Additionally, the targeted screening and treatment of LTBI in migrant individuals at a higher risk of previous TB exposure, who have already arrived in Canada, may also reduce the rates of active TB disease.Footnote 43

Moving Forward

Now is the time for collective action that will guide the elimination of TB in Canada. We have an opportunity to build on the current momentum being generated by: renewed relationships with First Nations, Inuit and Métis; strong community leadership; and new, focussed investments. TB is an infectious disease that disproportionately affects those who are at risk because they have less. It thrives in close living quarters, in people experiencing barriers to health care. The work of the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami shows us that TB elimination is within our reach when guided by a holistic strategy anchored in core principles, including respect and listening to people with lived experience.

Moving forward together, we must:

Harness collaboration - There has never been a more timely opportunity to champion collaborative action between sectors on two key fronts - improving the social determinants of health that address underlying risk factors; and providing support to strengthen TB diagnosis and management. Investments made to improve housing, income support, HIV prevention awareness, prevention of problematic substance use and anti-smoking campaigns will not only address the social factors that place people at risk, but deliver health benefits that extend well beyond preventing TB. Coordinating health promotion messaging among all partners in health will have a more powerful impact than independent efforts.

Support community-led solutions - The right solutions to this complex social disease will be driven by the communities themselves. Community leaders and champions are the key to success, whether they are respected elders, or a new generation of young and aware citizens. Efforts to eliminate TB can only succeed within a supportive environment that respects, understands and leverages language, culture, and the historical context in which decisions are made.

Sustain our efforts - Technological advancements, research and medical solutions to improve diagnosis and treatment of LTBI will provide part of the solution to break the cycles of TB reactivation that lead to outbreaks and antimicrobial resistance. Success depends upon all partners and stakeholders sustaining the effort over the long term, embracing culturally appropriate and holistic approaches that build on the strengths and resiliency of individuals and communities.

End the stigma and discrimination associated with TB - The underlying social, cultural, and historical factors that lead to shame and silence around TB need to be challenged through determined health education efforts. Indigenous and foreign-born people deserve the support that empowers them to seek diagnosis, treatment and care.

Levelling the playing field so that all Canadians can enjoy health will require true collaboration and innovative approaches. But everything is possible if we focus on improving the underlying conditions that affect health. In doing so, we can make a realistic push to end TB in Canada once and for all, while also promoting better overall health and quality of life for individuals, families and communities from coast to coast to coast.

Annex

Source: Vachon, J., Gallant, V., Siu, W. (2018). Tuberculosis in Canada, 2016. Canada Communicable Disease Report, 44(3/4), 75-81.

Figure 2 - Text description

| Population Group | Rate per 100,000 | Active TB Disease Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Inuit | 170 | 114 |

| First Nations - on reserve | 34 | 150 |

| Foreign-born | 15 | 1213 |

| First Nations - off reserve | 15 | 56 |

| Métis | 2 | 10 |

| Canadian-born non-indigenous | 0.6 | 135 |

| Canada (overall) | 5 | 1737 |

Source: Vachon, J., Gallant, V., Siu, W. (2018). Tuberculosis in Canada, 2016. Canada Communicable Disease Report, 44(3/4), 75-81.

Figure 4 - Text description

| Population Group | Rate Ratio |

|---|---|

| Inuit | 296 |

| Indigenous (overall) | 41 |

| Foreign-born | 26 |

Source: Vachon, J., Gallant, V., Siu, W. (2018). Tuberculosis 2016 - Supplementary Tables. Web exclusive. Canada Communicable Disease Report, 44(3/4).

Figure 5 - Text description

| Reporting year | First Nations on-reserve | First Nations off-reserve | Métis | Inuit | Foreign- born | Canadian born Non-Indigenous | Canada (Overall) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 31.5 | 26.3 | 7.2 | 115.1 | 14.9 | 0.9 | 5.1 |

| 2007 | 29.7 | 24.2 | 7.5 | 85.2 | 14.8 | 0.7 | 4.8 |

| 2008 | 26.8 | 28 | 6.1 | 160 | 14.5 | 0.9 | 4.9 |

| 2009 | 27 | 24.3 | 5.4 | 157.1 | 14.4 | 1 | 4.9 |

| 2010 | 23.7 | 20 | 5.4 | 200 | 14.1 | 0.7 | 4.7 |

| 2011 | 21.2 | 16.4 | 4.4 | 166.7 | 14.7 | 0.7 | 4.7 |

| 2012 | 23.8 | 18.7 | 2.2 | 243.9 | 14.6 | 0.7 | 4.9 |

| 2013 | 30.8 | 11.4 | 3.5 | 139.4 | 17.4 | 0.6 | 4.7 |

| 2014 | 21.7 | 15.2 | 3.6 | 177.6 | 14.2 | 0.6 | 4.5 |

| 2015 | 20.4 | 11.1 | 2.2 | 164.7 | 14.9 | 0.6 | 4.6 |

| 2016 | 34.1 | 14.5 | 2.1 | 170.1 | 15.2 | 0.6 | 4.8 |

Source: Statistics Canada. (2015). The Early Learning Experiences of Inuit Children in Canada. Statistics Canada.

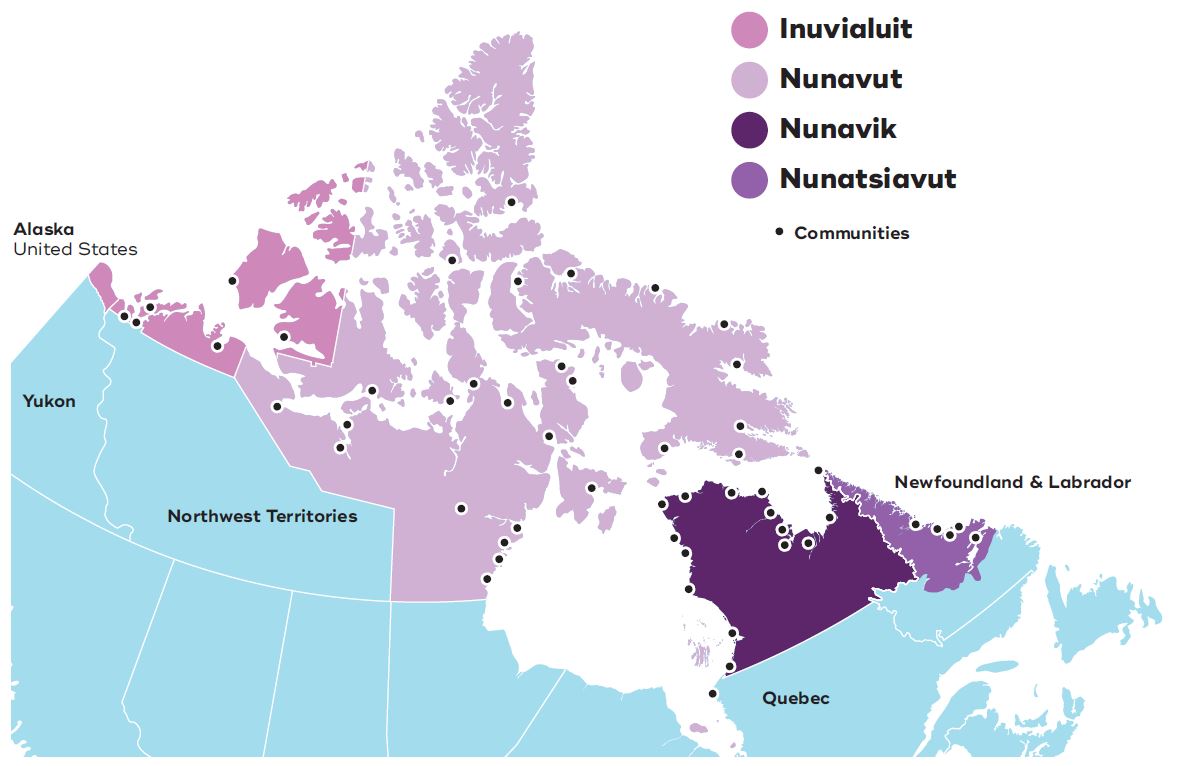

Image 3 - Text description

This map depicts the four Inuit Regions in Canada: The Inuvialuit Region in the Northwest Territories, the territory of Nunavut, Nunavik in northern Quebec, and Nunatsiavut in northern Labrador.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2014). Tuberculosis Prevention and Control in Canada: A Federal Framework for Action. Public Health Agency of Canada.

- Footnote 2

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2014). Canadian Tuberculosis Standards, 7th Edition: 2014. Public Health Agency of Canada.

- Footnote 3

-

World Health Organization (2017). Global tuberculosis report 2017. Available: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/

- Footnote 4

-

Vachon, J., Gallant, V., Siu, W. (2018). Tuberculosis in Canada, 2016. Canada Communicable Disease Report, 44(3/4), 75-81.

- Footnote 5

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2015). Tuberculosis in Canada 2012. Ottawa ON: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada.

- Footnote 6

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2013). The Chief Public Health Officer's Report on the State of Public Health in Canada, 2013: Infectious Disease - The Never-ending Threat. Ottawa ON: Public Health Agency of Canada.

- Footnote 7

-

Ronald, L. A., Campbell, J. R., Balshaw, R. F., Romanowski, K., Roth, D. Z., Marra, F., Cook, V. J., Johnston, J. C. (2018). Demographic predictors of active tuberculosis in people migrating to British Columbia, Canada: a retrospective cohort study. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 190(8), E209-E216.

- Footnote 8

-

Pepperell, C. S., Granka, J. M., Alexander, D. C., Behr, M. A., Chui, L., Gordon, J., Guthrie, J. L., Jamieson, F. B., Langlois-Klassen, D., Long, R., Nguyen, D., Wobeser, W., Feldman, M. W. (2011). Dispersal of Mycobacterium tuberculosis via the Canadian fur trade. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(16), 6526-6531.

- Footnote 9

-

Canadian Public Health Association. History of Public Health - TB and Aboriginal People. Available: https://www.cpha.ca/tb-and-aboriginal-people

- Footnote 10

-

Truth and Reconciliation Commission. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future. Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Available: http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Honouring_the_Truth_Reconciling_for_the_Future_July_23_2015.pdf

- Footnote 11

-

Al-Jahdali, H., Memish, Z. A., Menzies, D. (2003). Tuberculosis in association with travel. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 21(2), 125-130.

- Footnote 12

-

Statistics Canada. (2017). Immigration and ethnocultural diversity: Key results from the 2016 Census. Statistics Canada.

- Footnote 13

-

Olofsson, E., Holton, T., Partridge, I. (2008). Negotiating identities: Inuit tuberculosis evacuees in the 1940s-1950s. Études/Inuit/Studies, 32(2), 127-149.

- Footnote 14

-

Narasimhan, P., Wood, J., Macintyre, C.R., & Mathai, D. (2013). Risk Factors for Tuberculosis. Pulmonary Medicine, 2013, 1-11.

- Footnote 15

-

Clark, M., Riben, P., Nowgesic, E. (2002). The association of housing density, isolation and tuberculosis in Canadian First Nations communities. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(5), 940-945.

- Footnote 16

-

Labrador Grenfell Health. "If You Puff, Don't Pass" Poster. Available: http://www.lghealth.ca/index.php?pageid=313

- Footnote 17

-

Dhavan, P., Dias, H. M., Creswell, J., Weil, D. (2017). An overview of tuberculosis and migration. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 21(6), 610-623.

- Footnote 18

-

Gibson, N., Cave, A., Doering, D., Ortiz, L., Harms, P. (2005). Socio-cultural factors influencing prevention and treatment of tuberculosis in immigrant and Aboriginal communities in Canada. Social Science & Medicine, 61(5), 931-942.

- Footnote 19

-

Health Canada. (2012). Epidemiology of Tuberculosis in First Nations Living On-Reserve in Canada, 2000-2008. Ottawa ON: Health Canada.

- Footnote 20

-

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. (2014). Social determinants of Inuit health in Canada. Ottawa: Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami.

- Footnote 21

-

Khan, F. A., Fox, G. J., Lee, R. S., Riva, M., Benedetti, A., Proulx, J. F., Jung, S., Hornby, K., Behr, M.A., Menzies, D. (2016). Housing and tuberculosis in an Inuit village in northern Quebec: a case-control study. Canadian Medical Association Journal Open, 4(3), E496-E506.

- Footnote 22

-

Public Health Agency of Canada, the Pan - Canadian Public Health Network, Statistics Canada, and the Canadian Institute of Health Information. (2017). Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Data Tool, 2017 Edition.

- Footnote 23

-

Statistics Canada. (2017). The Housing Conditions of Aboriginal people in Canada. Statistics Canada.

- Footnote 24

-

Fox, G. J., Lee, R. S., Lucas, M., Khan, F. A., Proulx, J. F., Hornby, K., Jung, S., Benedetti, A., Behr, M.A., Menzies, D. (2015). Inadequate Diet Is Associated with Acquiring Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection in an Inuit Community. A Case-Control Study. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 12(8), 1153-1162.

- Footnote 25

-

Bhullar, K.S. (2017). Nutritional Intervention for Active Tuberculosis: Relevance to Nunavut Tuberculosis Control and Elimination Program. Journal of Pharmacology Reports, 2:1.

- Footnote 26

-

Patterson, M., Flinn, S., Barker, K. (2018). Addressing tuberculosis among Inuit in Canada. Canada Communicable Disease Report, 44(3/4), 82-85.

- Footnote 27

-

Reitmanova, S., Gustafson, D. (2012). Rethinking immigrant tuberculosis control in Canada: from medical surveillance to tackling social determinants of health. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 14(1), 6-13.

- Footnote 28

-

Gardam, M., Verma, G., Campbell, A., Wang, J., Khan, K. (2009). Impact of the patient-provider relationship on the survival of foreign born outpatients with tuberculosis. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 11(6), 437-445.

- Footnote 29

-

Gao, J., Berry, N. S., Taylor, D., Venners, S. A., Cook, V. J., & Mayhew, M. (2015). Knowledge and perceptions of latent tuberculosis infection among Chinese immigrants in a Canadian urban centre. International Journal of Family Medicine, 2015.

- Footnote 30

-

World Health Organization. (2018). About Social Determinants of Health. Available: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/

- Footnote 31

-

National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health. (2013). Let's talk: Health equity. Antigonish, NS: National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, St. Francis Xavier University.

- Footnote 32

-

Bambury, B. (2017, September 15). Day 6 [Television broadcast]. Toronto, Canada: CBC Radio Canada. Available: http://www.cbc.ca/radio/day6/episode-355-robot-surgeons-surviving-the-eye-of-irma-the-disaster-artist-a-homegrown-tb-crisis-and-more-1.4287163/homegrown-tb-crisis-why-a-preventable-disease-persists-among-canada-s-inuit-1.4287176

- Footnote 33

-

National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health and National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Disease. (2014). Public Health Speaks: Tuberculosis and the Determinants of Health. Antigonish, NS: National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, St. Francis Xavier University.

- Footnote 34

-

Houben, R. M., Dodd, P. J. (2016). The global burden of latent tuberculosis infection: a re-estimation using mathematical modelling. Public Library of Science Medicine, 13(10), e1002152.

- Footnote 35

-

World Health Organization. (2014). Towards tuberculosis elimination: an action framework for low-incidence countries. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/132231/1/9789241507707_eng.pdf?ua=1

- Footnote 36

-

World Health Organization. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Available: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/final_report/media/csdh_report_wrs_en.pdf

- Footnote 37

-

Philpott, J. (2018). Canada's efforts to ensure the health and wellbeing of Indigenous peoples. The Lancet.

- Footnote 38

-

Assembly of First Nations. (2013). National First Nations Housing Strategy. Ottawa ON: Assembly of First Nations. Available: http://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/housing/afn_national_housing_strategy.pdf

- Footnote 39

-

Department of Finance Canada. (2018). Equality + Growth: A Strong Middle Class. Available: https://www.budget.canada.ca/2018/docs/plan/budget-2018-en.pdf

- Footnote 40

-

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. (2017). Tuberculosis Task Force. Ottawa ON: Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-northern-affairs/news/2017/10/tuberculosis_taskforce.html

- Footnote 41

-

Craig, G. M., Daftary, A., Engel, N., O'Driscoll, S., Ioannaki, A. (2017). Tuberculosis stigma as a social determinant of health: a systematic mapping review of research in low incidence countries. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 56, 90-100.

- Footnote 42

-

Alvarez, G. G., VanDyk, D. D., Aaron, S. D., Cameron, D.W., Davies, N., Stephen, N., Mallick, R., Momoli, F., Moreau, K., Obed, N., Baikie, M., Osborne, G. (2014). Taima (stop) TB: the impact of a multifaceted TB awareness and door-to-door campaign in residential areas of high risk for TB in Iqaluit, Nunavut. Public Library of Science One, 9(7), e100975.

- Footnote 43

-

Greenaway, C., Sandoe, A., Vissandjee, B., Kitai, I., Gruner, D., Wobeser, W., Pottie, K., Ueffing, E., Menzies, D., Schwartzman, K. (2011). Tuberculosis: evidence review for newly arriving immigrants and refugees. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 183(12), E939-E951.

- Footnote 44

-

Tomás, B. A., Pell, C., Cavanillas, A. B., Solvas, J. G., Pool, R., Roura, M. (2013). Tuberculosis in migrant populations. A systematic review of the qualitative literature. Public Library of Science One, 8(12), e82440.

- Footnote 45

-

Collins, B.F. (2017, March 23). Emotional exhibit at city hall for world TB day. The Toronto Observer. Available: https://torontoobserver.ca/2017/03/23/emotional-exhibit-at-city-hall-for-world-tb-day/

- Footnote 46

-

World Health Organization. (2008). WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system 2008 global summary. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/69990/1/WHO_IVB_2008_eng.pdf

- Footnote 47

-

Kaufmann, S. H. (2010). Novel tuberculosis vaccination strategies based on understanding the immune response. Journal of Internal Medicine, 267(4), 337-353.

- Footnote 48

-

Sterling, T. R., Villarino, M. E., Borisov, A. S., Shang, N., Gordin, F., Bliven-Sizemore, E., Hackman, J., Hamilton, C. D., Menzies, D., Kerrigan, A., Weis, S. E., Weiner, M., Wing, D., Conde, M. B., Bozeman, L., Horsburgh, R., Chaisson, R. E., (2011). Three months of rifapentine and isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection. New England Journal of Medicine, 365(23), 2155-2166.

- Footnote 49

-

Pease, C., Amaratunga, K. R., Alvarez, G. G. (2017). A shorter treatment regimen for latent tuberculosis infection holds promise for at-risk Canadians. Canada Communicable Disease Report, 43(3/4), 67-71.

- Footnote 50

-

Health Canada. (2018). List of Drugs for an Urgent for an Urgent Public Health Need. Health Canada. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/access-drugs-exceptional-circumstances/list-drugs-urgent-public-health-need.html

- Footnote 51

-

Alvarez, G. G., Van Dyk, D. D., Desjardlns, M., Yasseen, A. S., Aaron, S. D., Cameron, D. W., Obed, N., Baikie, M., Pakhale, S., Denklnger, C.M., Sohn, H. (2015). The feasibility, accuracy, and impact of Xpert MTB/RIF testing in a remote aboriginal community in Canada. Chest, 148(3), 767-773.

- Footnote 52

-

Alvarez, G. G., Van Dyk, D.D., Davies, N., Aaron, S.D., Cameron, D.W., Desjardins, M., Mallick, R., Obed, N., Baikie, M. (2014). The feasibility of the interferon gamma release assay and predictors of discordance with the tuberculin skin test for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in a remote Aboriginal community. Public Library of Science One, 9(11), e111986.

- Footnote 53

-

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. (2013). Inuit-specific tuberculosis (TB) strategy. Ottawa, ON. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami.

- Footnote 54

-

Schwartzman, K., Oxlade, O., Barr, R. G., Grimard, F., Acosta, I., Baez, J., Ferreira, E., Melgen, R. E., Morose, W., Salgado, A.C., Jacquet, V., Maloney, S. (2005). Domestic returns from investment in the control of tuberculosis in other countries. New England Journal of Medicine, 353(10), 1008-1020.

- Footnote 55

-

Alvarez, G.G., Gushulak, B., Rumman, K.A., Altpeter, E., Chemtob, D., Douglas, P., Erkens C., Helbling P., Hamilton I., Jones J., Matteelli, A., Paty M.C., Posey D.L., Sagebiel D., Slump E., Tegnell A., Valín E.R., Winje B.A., Ellis, E. (2011). A comparative examination of tuberculosis immigration medical screening programs from selected countries with high immigration and low tuberculosis incidence rates. BioMed Central Infectious Diseases, 11(3).

- Footnote 56

-

Stop TB Partnership. (2016). Canada announces major contribution for Stop TB Partnership's TB REACH Initiative. Available: http://www.stoptb.org/news/stories/2016/ns16_020.asp

- Footnote 57

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2017). Tuberculosis: Drug resistance in Canada 2015. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/tuberculosis-drug-resistance-canada-2015.html

- Footnote 58

-

Abubakar, I., Zignol, M., Falzon, D., Raviglione, M., Ditiu, L., Masham, S., Adetifa, I., Ford, N., Cox, H., Lawn, S.D., Marais, McHugh, T., Mwaba, P., Bates, M., Lipman, M., B.J., Zijenah, L., Logan, S., McNemey R., Zumla, A., Sarda, K., Nahid, P., Hoelscher, M., Pletschette, M., Memish, Z.A., Kim, P., Hafner, R., Cole, S., Battista Migliori, G., Maeurer, M., Schito, M., Zumla, A. (2013). Drug-resistant tuberculosis: time for visionary political leadership. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 13(6), 529-539.

- Footnote 59

-

Khan, K., Hirji, M. M., Miniota, J., Hu, W., Wang, J., Gardam, M., Rawal, S., Ellis, E., Chan, A., Creatore, M.I., Rea, E. (2015). Domestic impact of tuberculosis screening among new immigrants to Ontario, Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 187(16), E473-E481.

- Footnote 60

-

Newman, T. (2017). "There is a TB crisis in Nunavut at this very moment" - Stephen Lewis. Available: http://www.feedingnunavut.com/tb-crisis-in-nunavut/

- Footnote 61

-

World Health Organization. (2004). Diseases of poverty and the 10/90 gap. Available: http://www.who.int/intellectualproperty/submissions/InternationalPolicyNetwork.pdf

- Footnote 62

-

Grant, K. (2017, March 25). Doctor finds a new way to fight tuberculosis in Nunavut. The Globe and Mail. Available: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/health-and-fitness/health/doctor-finds-new-way-to-fight-tuberculosis-in-nunavut/article19687654/

Page details

- Date modified: