Criminal Careers of Intimate Partner Abusers: Generalists or Specialists?

By Frédéric Ouellet, Ph.D.

School of Criminology, Université de Montréal

International Centre for Comparative Criminology (ICCC)

Centre de recherche de l'Institut universitaire en santé mentale de Montréal

With the collaboration of:

Arthur Nouvian, B.Sc., School of Criminology, Université de Montréal

Elise Soulier, M.Sc., School of Criminology, Université de Montréal

Valérie Thomas, M.Sc., Cégep régional de Lanaudière à L'Assomption

February 8, 2021

The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada or the Government of Canada.

Table of contents

Summary

Studies on criminal careers conducted in a number of countries show that many offenders involved in intimate partner violence do not specialize solely in this type of offence. Some empirical literature points out that offenders who commit serious and frequent domestic assaults, particularly in an intimate context, are also more likely to engage in other types of violent and criminal behaviours. This research report focuses on this issue by attempting to determine whether individuals convicted of intimate partner violence in Canada are also involved in other types of violent and criminal behaviours outside the intimate context. To answer this question, this study is based on interviews conducted between 2018 and 2020 with 121 incarcerated violent spouses (with provincial sentences). The majority of offenders who took part in these interviews did not just commit intimate partner violence, but also diversified into other crimes. This was observed over the span of an entire criminal career or within a recent time window. A detailed examination of criminal careers over a three-year time window in three years preceding the current term of incarceration (the study period) shows that in many cases, the nature of the offences committed outside the intimate context is vast and that these crimes are committed frequently. More than half of the offenders had committed at least one crime with the potential to cause bodily harm to a person outside the family and close to a third had committed an act with the potential for causing serious bodily harm. In an intimate context, all offenders had committed acts associated with bodily harm. The intimate partner violence perpetrated by these offenders took various forms. It was diversified, frequent or intense, and the more serious behaviours with the potential for causing injuries were recurrent. The individual characteristics of offenders and those of their criminal careers suggest that these are individuals who are akin to chronic, persistent offenders described by many criminology authors. These individuals are known for committing a higher number of crimes, thus requiring sustained intervention and mobilizing more resources. Therefore, there is a real interest in identifying these individuals.

Key words:

Intimate partner violence; violent crime; bodily harm; criminal career; offenders; self‑reported data; official data.

Executive Summary

This report presents an analysis of the official and self‑reported criminal career of individuals convicted of domestic violence, particularly in the intimate partner violence subcategory. Special attention is paid to the observation of violent behaviours committed in an intimate context, but also to violent behaviours and other crimes that these offenders might have committed outside the intimate context. The overall aim is to determine whether individuals convicted of intimate partner violence in Canada are also involved in other types of violent and criminal behaviours outside the intimate context. This research report is based on official and self‑reported data compiled as part of a project focused on the criminal pathways and the processes leading to offending among offenders who committed intimate partner violence. The analyses are based on interviews conducted between 2018 and 2020 with 121 incarcerated violent spouses (with provincial sentences). Six provincial correctional institutions in Quebec (sentence of less than two years) were solicited and participated in recruiting offenders.

The criminal career overview included an examination of (official and self‑reported) criminal participation, age at first crime, the nature of offences committed, criminal diversification and offence frequency. Lastly, additional analyses were performed to not only examine offenders’ characteristics, but also identify those who would be most inclined to commit serious violent offences.

Below is a summary of the results obtained based on specific objectives:

Objective A: criminal participation.

- Over the span of an entire criminal career, 94.3% of offenders report participating in at least two spheres of criminal activity, whereas 71.1% report participating in the three spheres of crime under study (intimate partner violence, violent crimes and other crimes).

- In the three-year period preceding the current term of incarceration, participation in two spheres of criminality is 73.6%, and 32.2% of participants report being involved in all three spheres of criminal activity.

- Criminal specialization is rare among the offenders interviewed. Very few specialize in intimate partner violence, both over the span of their entire criminal career (5.8%) and during the three‑year window (26.4%).

- Official (arrest and incarceration) data pose significant limitations in the reconstruction of criminal pathways. It can be stated with confidence that official data underestimate criminal participation, especially as concerns intimate partner violence.

- Most offenders committed serious physical assault or caused serious injuries to their partner.

Objective B: parameters of intimate partner violence, age at first crime, nature of offences, criminal diversification and offence frequency.

Intimate partner violence

- All offenders had committed violent acts with the potential to cause bodily harm.

- Most offenders committed three forms of intimate partner violence (psychological, economic and physical).

- Violent behaviours of a psychological and physical nature are diverse and frequent.

Crimes outside the intimate context

- Participation in a greater number of spheres of criminal activity was associated with an earlier age of initiation into crime.

- The nature of offences is vast. For most offenders, criminal activity is diversified and frequent.

- More than half of offenders committed at least one crime with the potential to cause bodily harm to a person outside the family.

- Close to a third of offenders committed a criminal act with the potential for causing serious bodily harm outside the domestic context.

Objective C: offender characteristics and prediction of serious violent behaviours.

- The prevalence of a number of risk factors is high in the sample.

- The intensity of psychological violence perpetrated during the study period is the best predictor of physical assault (frequency of physical assault, occurrence of serious physical assault and injuries).

- The occurrence of crimes with the potential to cause bodily harm outside the intimate context is effectively predicted by criminal career parameters.

The results of this research report tend to show that for offenders who commit intimate partner violence, this form of violence is merely the result and projection of other types of crimes committed outside the home. These aspects thus corroborate the notion of generalized crime and emphasize the importance of considering the criminal history of perpetrators of intimate partner violence. It can therefore be suggested that intimate partner violence is a mere manifestation of a variety of criminal behaviours. This means that intimate partner violence is often part of a broader constellation of anti‑social behaviours. Strict intervention is therefore recommended when dealing with individuals who demonstrate chronic delinquency, an approach that helps reduce the prevalence and commission of violence between partners.

It is therefore difficult to believe that the violent behaviours of the offenders interviewed do not extend to other intimate relationships and, therefore, other forms of domestic violence. Studies that have looked at the connection between intimate partner violence and other forms of domestic violence show that, in many situations, violence occurs concurrently within the same family. It would therefore be advisable to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the phenomenon to report on its complexity and further study the complex linkages between instances of violence in intimate relationships.

Glossary

Assault with weapon or causing bodily harm (levels 2 and 3): Carry, use, or threaten to use a weapon or an imitation of a weapon; cause bodily harm in committing an assault; wound, maim or disfigure any person; or endanger the life of any person in committing an assault (Criminal Code 1985).

Bodily harm: “[A]ny hurt or injury to a person that interferes with the health or comfort of the person and that is more than merely transient or trifling in nature” (Criminal Code 1985).

Break-in (breaking and entering): “[B]reaks and enters a place with intent to commit an indictable offence therein, breaks and enters a place and commits an indictable offence therein; or breaks out of a place after committing an indictable offence therein or entering the place with intent to commit an indictable offence therein” (Criminal Code 1985).

Business fraud: Generally refers to explicit violations of the law, but can also include practices on the fringes of the law, which consist in taking advantage of the vagueness of a regulation, putting several normative systems in competition or benefiting from a previously negotiated exemption (Spire 2013, p. 10).

Common assault: “A person commits an assault when without the consent of another person, he applies force intentionally to that other person, directly or indirectly; he attempts or threatens, by an act or a gesture, to apply force to another person, if he has, or causes that other person to believe on reasonable grounds that he has, present ability to effect his purpose; or while openly wearing or carrying a weapon or an imitation thereof, he accosts or impedes another person or begs” (Criminal Code 1985).

Contraband: “[F]ail to mark imported goods; mark imported goods in a deceptive manner so as to mislead another person as to the country of origin or geographic origin of the goods; or with intent to conceal the information given by or contained in the mark, alter, deface, remove or destroy a mark on imported goods made as required by the regulations made under subsection 19(2) of the Customs Tariff” (Customs Act 1985).

Crimes of acquisition: Robbery, break‑in, motor vehicle theft, theft, fraud, business fraud.

Domestic violence: The violent behaviours that can be included in the definition of domestic violence are wide-ranging. The empirical literature focuses more closely on physical, sexual and verbal violence, and on psychological abuse, financial exploitation and neglect that can occur in kinship or intimate relationships. According to Barnett and his colleagues (2005), the nature of the relationship between the abuser and the victim can lead to subcategories of domestic violence: intimate partner violence, parental violence against own children, child violence against own parents or elderly relatives, as well as sibling violence.

Drug sale and distribution: Drug trafficking is defined as the selling, giving, administering, transporting, sending or delivering of a drug (Criminal Code 1985).

Fraud: “[B]y deceit, falsehood or other fraudulent means…defrauds the public or any person, whether ascertained or not, of any property, money or valuable security or any service” (Criminal Code 1985). This category includes fraud by service card, by cheque, by fraudulently obtaining board, food or transportation, through impersonation, through false government or insurance claims, through telemarketing, by means of a computer, through insider trading, by manipulating stock market transactions and the like.

Generalist offender: A generalist offender commits various offences over time, without any propensity for one criminal act in particular or a specific pattern of criminal acts (Baker et al. 2013).

Homicide: This general category comprises the following offences: first degree murder (premeditated murder); second degree murder (unpremeditated murder); manslaughter (reduced murder because the person who committed it acted in a fit of anger caused by a sudden provocation); and infanticide (unintentional act or omission committed by a female which has the effect of causing the death of her newborn child) (Criminal Code 1985).

Illegal betting: “Every person who keeps a common gaming house or common betting house is guilty of (a) an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than two years; or (b) an offence punishable on summary conviction….Every one who (a) is found, without lawful excuse, in a common gaming house or common betting house, or (b) as owner, landlord, lessor, tenant, occupier or agent, knowingly permits a place to be let or used for the purposes of a common gaming house or common betting house, is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction” (Criminal Code 1985).

Intimate partner violence: Intimate partner violence is defined as a specific, interpersonal form of violence characterized by the existence of an intimate bond between the perpetrator and the victim, of any sexual orientation. It includes manifestations of violence (which can be psychological, verbal, economic, physical or sexual) among married or unmarried couples, couples who do or do not live together, or couples who are in a relationship, are separated or have already broken up. Most often perpetrated as coercive behavior with the intention of controlling one’s intimate partner, intimate partner violence entails violence of a physical, sexual and/or psychological nature (Jaquier and Guay 2013), as well as stalking (Gover 2011). The Criminal Code does not specifically provide for intimate partner violence offences. The notion of criminal intimate partner violence refers to the context in which criminal acts are perpetrated and to the nature of the bond between the perpetrator and the victim.

Loan-sharking: In Canada, loan-sharking is officially designated as an offence under the Criminal Code if the effective rate (including fees and penalty payments) exceeds 60% per annum. “Despite any other Act of Parliament, every one who enters into an agreement or arrangement to receive interest at a criminal rate, or receives a payment or partial payment of interest at a criminal rate, is guilty” (Criminal Code 1985).

Market-based crimes: Drug sale and distribution, contraband, loan-sharking, illegal betting, sex trade, possession of stolen property and other market-based crimes.

Motor vehicle theft: “Every one who commits theft is, if the property stolen is a motor vehicle” (Criminal Code 1985).

Other crimes (lucrative crime): Crimes of acquisition and market-based crimes.

Possession of stolen property: “Every person who, without lawful excuse, makes, possesses, sells, offers for sale, imports, obtains for use, distributes or makes available a device that is designed or adapted primarily [to commit an offence], knowing that the device has been used or is intended to be used for that purpose” (Criminal Code 1985).

Robbery (holdup): “Every one commits robbery who steals, and for the purpose of extorting whatever is stolen or to prevent or overcome resistance to the stealing, uses violence or threats of violence to a person or property; steals from any person and, at the time he steals or immediately before or immediately thereafter, wounds, beats, strikes or uses any personal violence to that person; assaults any person with intent to steal from him; or steals from any person while armed with an offensive weapon or imitation thereof” (Criminal Code 1985).

Sex trade: Procuring involves enticing, soliciting, encouraging or forcing someone to engage in prostitution for gain, including living on the avails of prostitution (Criminal Code 1985).

Sexual assault: “[A]n assault committed in circumstances of a sexual nature such that the sexual integrity of the victim is violated” (Criminal Code 1985).

Specialist offender: A specialist offender is more likely to repeat the same crime or offence over time (Baker et al. 2013).

Theft: “Every one commits theft who, having received, either solely or jointly with another person, money or valuable security or a power of attorney for the sale of real or personal property, with a direction that the money or a part of it, or the proceeds or a part of the proceeds of the security or the property shall be applied to a purpose or paid to a person specified in the direction, fraudulently and contrary to the direction applies to any other purpose or pays to any other person the money or proceeds or any part of it” (Criminal Code 1985).

Threats or extortion: “Every one commits an offence who, in any manner, knowingly utters, conveys or causes any person to receive a threat to cause death or bodily harm to any person; to burn, destroy or damage real or personal property; or to kill, poison or injure an animal or bird that is the property of any person.” “Every one commits extortion who, without reasonable justification or excuse and with intent to obtain anything, by threats, accusations, menaces or violence induces or attempts to induce any person, whether or not he is the person threatened, accused or menaced or to whom violence is shown, to do anything or cause anything to be done.” (Criminal Code 1985)

Violent crimes: Common assault, assault with a weapon or causing bodily harm, threats or extortion, sexual assault, homicides, other violent crimes.

Introduction

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) assesses the risks of domestic violence in the context of immigration in Canada in order to improve policies aimed at preventing domestic violence and better protecting individuals sponsored as members of the family class. This approach aligns with one of the objectives of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, which is to protect public health and safety and to maintain the security of Canadian society. It also falls within the measures taken by the Government of Canada to protect vulnerable persons, which include Canada’s Strategy to Prevent and Address Gender‑Based Violence, established in 2017.

There is no consensus as to the definition of domestic violence. The violent behaviours that can be included in the definition of domestic violence are wide-ranging. The empirical literature focuses more closely on physical, sexual and verbal violence, and on psychological abuse, financial exploitation and neglect that can occur in kinship or intimate relationships. According to Barnett and his colleagues (2005), the nature of the relationship between the abuser and the victim can lead to subcategories of domestic violence: intimate partner violence, parental violence against own children, child violence against own parents or elderly relatives, as well as sibling violence. This report takes a specific look at perpetrators of intimate partner violence, as this is a widespread subcategory of domestic violence, and one of the best documented, and since the data used for this report were limited for other subcategories of domestic violence. Nevertheless, the final part of this report will discuss other types of domestic violence by establishing linkages between the results of this report and these other types of violence.

Intimate partner violence is defined as a specific, interpersonal form of violence characterized by the existence of an intimate bond between the perpetrator and the victim, of any sexual orientation. It includes acts of violence among married or unmarried couples, couples who do or do not live together, or couples who are in a relationship, are separated or have already broken up. Most often perpetrated as coercive behavior with the intention of controlling one’s intimate partner, intimate partner violence entails violence of a physical, sexual and/or psychological nature (Jaquier and Guay 2013), as well as stalking (Gover 2011).

From a global perspective, the Intimate Violence Against Women Survey, conducted in 11 countries around the world, shows that on average 15% of women experience some form of violence at the hands of a partner during their lifetime (Johnson, Ollus and Nevala 2008). In this study, the country with the highest rate of intimate partner violence is Mozambique at 40%, while the one with the lowest is Switzerland at close to 10%.

Looking at intimate partner violence against both men and women, in the United States, 11% of the population reports having experienced physical violence at the hands of an intimate partner during their lifetime (Klevens, Simon and Chen 2012). These numbers vary slightly from one study to another. Therefore, by examining a sample of 70,000 individuals, Breiding, Black and Ryan (2008) show that approximately 20% of American women and 11% of American men were physically assaulted by a partner during their lifetime, or still are. As a result, approximately 1,200 deaths related to intimate partner violence are reported in the United States every year, in addition to the 2 million women and 600,000 men who are injured by a spouse or former spouse (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2003). However, the magnitude of this phenomenon is very difficult to estimate. Victim silence continues to be a major obstacle in assessing the prevalence of intimate partner violence, and it is estimated that, on average, two‑thirds of such cases of violence are not reported to police or judicial authorities (Johnson, Ollus and Nevala 2008).

In Canada specifically, the Canadian General Social Survey (GSS) indicates that in the 12 months preceding their participation in the survey, 1.8% of women and 1.8% of men say they were victims of violence at the hands of a spouse or former spouse (Laroche 2007). Despite this parity in self‑reported data, police data report a much higher proportion of female victims. In 2007, over 40,000 incidents of intimate partner violence were reported in Canadian police statistics, more than 80% of which involved female victims (Department of Justice 2010). It is therefore possible that men who are victims of intimate partner violence do not report these incidents to police and file fewer formal complaints.

The above‑mentioned studies discuss a major phenomenon involving many victims across various cultures and populations, with the consequences of intimate partner violence felt by individuals and society alike. From an economic viewpoint, an estimated $5.8 billion was thus spent on medical care and loss of work in the United States in 2003 as a result of intimate partner violence (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2003). In Canada, based on a sample of 309 Canadian women who left a violent partner in the previous 20 months, Varcoe et al. (2011) estimate intimate partner violence to have cost more than $13,162 per woman (public and private sectors combined). This translates into a national annual cost of $6.9 billion for women aged 19 to 65 who left a violent partner.

Moreover, victims of intimate partner violence living in fear on a daily basis (Belknap and Sullivan 2002) have many health problems, particularly psychological and behavioural ones. These include depression, anxiety, post‑traumatic stress, and eating and sleep disorders, as well as self‑harm, substance abuse, avoidance and risky sexual behaviours (Barnett 2000; Coker et al. 2002; Ellsberg et al. 2008; Leserman and Drossman 2007; Herman 1992). Added to these are recurring physical health problems among victims, such as migraines, stroke or chronic illness (Brewer, Roy and Smith 2010; Coker et al. 2002).

The extent of this phenomenon and the costs it generates make this a major public health problem. Some victims find themselves experiencing violence at the hands of an intimate partner on a daily basis for many years of their lives. The empirical literature also reveals that individuals who commit intimate partner violence are also known to commit a higher number of crimes outside the intimate context, meaning that they require sustained intervention and mobilize more resources. There is therefore an interest in identifying these individuals. However, very few Canadian studies have made the effort to build a criminal profile of perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Are they actually generalists in their criminal careers? This research report aims to describe the pathways of Canadian perpetrators of intimate partner violence from the point of view of the abusers themselves. Before looking at the analysis of these pathways, the document will discuss the literature pertaining to such offenders and will then outline the objectives and the methodology of the research proposed here.

Literature review

The aim of this literature review is to understand what leads abusers to commit intimate partner violence by focusing on their criminal careers in particular. More specifically, the point is to examine the various pathways of these offenders and to analyze the various forms of criminality on their path. The first area of focus will be the risk factors that predict the transition to committing a criminal act in the case of intimate partner violence. Criminal careers will be examined next, ending with a scrutiny of empirical research to determine whether perpetrators of intimate partner violence commit other types of violent crimes.

Risk factors and circumstances

In criminology, circumstances and risk or vulnerability factors are the preferred topics of study to predict the transition to committing a criminal act. However, the circumstances and risk or vulnerability factors involved in intimate partner violence are partial and have essentially been shaped by the male intimate partner violence model, even though current research tends to correct this bias by studying female or non‑gender‑specific intimate partner violence. Therefore, the empirical literature has targeted contextual and individual factors that seem to favour a violent act within a romantic relationship. While some research cites circumstances that increase vulnerability and victimization, the goal here is to understand what characteristics influence the transition to committing a violent act in romantic relationships, that is, what drives decision‑making. In light of these bodies of work on the topic, personal, relational and contextual factors can be identified to explain or predict violent behaviour between intimate partners.

At the personal and relational levels, a child or an adolescent who witnesses intimate partner violence will be more likely to reproduce this behaviour in their future relationship, which Straus and Gelles (1990) call the intergenerational transmission of violence. Many authors identify delinquent or anti‑social behaviour during adolescence as a significant risk factor for intimate partner violence in early adulthood (Capaldi et al. 2012; Costa et al. 2015). Moffitt et al. (2000) also state that individuals who commit physical abuse before age 15 are more likely to commit intimate partner violence and that individuals with serious mental health disorders also have a higher risk of transitioning to offending.

In conducting a longitudinal study on the crimes and delinquency of 411 men born in the 1950s in a London neighbourhood (Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development, CSDD), some authors show that family factors (such as poor education, parental conflicts and low family income) indirectly increase the risk of intimate partner violence because this type of environment fosters anti‑social behaviour in adolescence (Lussier, Farrington and Moffitt 2009). The presence of a neurological deficit (low verbal IQ at age 10) plays a more direct role in this relationship (Lussier, Farrington and Moffitt 2009). In examining the interviews conducted at age 32 and 48 in this same sample, Theobald and Farrington (2012) focus on the accuracy of predictions of certain explanatory factors. They find that family factors (criminal father, broken family, poor supervision and relationship problems with parents) and individual factors (unpopularity, daring, impulsivity, aggressiveness and low verbal IQ) predict future intimate partner violence. Piquero, Theobald and Farrington (2014) add that these risk factors during early childhood are related to violent criminal behaviours and to intimate partner violence, but that they do not help explain such violence.

Some personality traits correlate with the commission of intimate partner violence: anger and low self‑esteem as well as anti‑social and borderline personality disorders (Dutton 1998). Alcohol consumption is also an external factor that turns out to be a recurring trait among perpetrators of intimate partner violence (Riggs, Caufield and Street 2000).

In terms of contextual factors, young people are overrepresented in literature on the topic. Moffitt et al. (2000) report that violence between intimate partners is strongly linked to partners living together at a young age, dropping out of school or becoming parents at a young age as well as to poverty and to family adversity. In addition, young couples are apparently under more personal and professional pressure than their elders, which presumably fosters conflicts (Godenzi et al. 2001). Marriage could also play a role in the commission of intimate partner violence. In some cases, perpetrators of intimate partner violence are apparently less likely to commit such acts when they are married (Akers and Keukinen 2009), while in others, this variable appears to be insignificant (Richards et al. 2012).

Nevertheless, the main ubiquitous risk factor in the literature appears to be the commission of crimes, generally speaking, particularly violent crimes. Individuals involved in persistent or serious anti‑social or criminal behaviours are at an especially high risk of committing intimate partner violence. In New Zealand, Woodward et al. (2002) measured the anti‑social behaviours of 495 young people aged 8 to 21 and noted that those with persistent, early anti‑social behaviour have a higher risk of engaging in intimate partner violence. In the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, Moffitt et al. (2002) followed a cohort of 477 individuals from birth until they turned 26. They showed that young people exhibiting a persistent pattern of serious anti‑social behaviours during adolescence were more likely to commit intimate partner violence at age 26 and to be convicted by a court for violence against women, compared to those whose anti‑social behaviours were within the norm. In England, Piquero et al. (2014) show that in a sample of 411 men (those from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development), both groups engaged in chronic delinquent behaviour (measured from ages 10 to 40) demonstrate a higher risk of committing physical intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Finally, in the United States, Herrenkohl et al. (2007) examine the association between patterns of violence in adolescence (13–18 years of age) and the commission of intimate partner violence at age 24 among 644 individuals. By identifying four different groups of pathways, they observe that those who commit chronic violence are more likely to report intimate partner violence compared to groups of non‑offenders and desisted offenders.

Thus, the longitudinal studies presented here show that active and chronic participation in a criminal career is a considerable risk factor in the commission of intimate partner violence. However, to fully understand the connection between these two components, we need to reconsider the criminal career theories by comparing the various empirical works attempting to establish a link between criminality in the broad sense and intimate partner violence, with particular attention to violent criminality.

Criminal careers of perpetrators of intimate partner violence

In recent decades, approaches involving theoretical explanations from multiple disciplines, such as psychology, sociology and criminology, have continuously attempted to explain the pathways and factors that play a role in individual criminal careers. Over the years, research has shown that a criminal career arises from many dynamic and static factors. The criminal career of an individual begins at a given age, with the commission of the first offences. That individual will then engage in offending at a frequency specific to them, will commit a variety of crimes and will then desist from crime at a given point in their life. Their career will be marked by successes (such as financial gains, peer recognition and progression in the hierarchy of the organization), but also failures (such as financial losses and court sentences). Their career will experience all sorts of fluctuations over time, with periods of abstinence and periods of intense criminality, and will include targeted or varied types of crimes. Multiple parameters can therefore be used to describe a criminal career, depending on the particular pathway (Piquero et al. 2003, 2007).

Research on the paths taken in a life of crime shows that general offending peaks between the end of adolescence and young adulthood, following a downward curve thereafter (Farrington 2008; Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990; Sweeten et al. 2013).

Two major trends emerge in relation to criminal careers (Laub and Sampson 1993). On the one hand, a large proportion of offenders will desist from crime in early adulthood (Piquero et al. 2007; Laub and Sampson 1993). Some provide maturing as an explanation (Moffitt 1993; Massoglia and Uggen 2010), while others claim that the social ties that people forge in early adulthood promote a more conventional lifestyle (Sampson and Laub 1993; Laub and Sampson 2003). On the other hand, a considerable continuity is observed in aggressiveness and anti‑social behaviour over time (Huesmann 2009; Piquero et al. 2012). This stability is said to be due to underlying characteristics that are unchanging, such as self‑control (Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990), an interaction between individual characteristics and environmental risk factors (Moffitt 1993), or a process of cumulative disadvantage in which the consequences of the anti‑social behaviours of an individual reduce that person’s chances of abandoning criminal behaviour (Sampson and Laub 1997). The formation of a stable intimate relationship in early adulthood is presumably a significant factor in abandoning general delinquency (Sampson and Laub 1993; Laub and Sampson 2003), which is apparently not the case for more serious criminals, for whom having an intimate relationship is an additional opportunity to exhibit anti‑social and violent behaviours (Moffitt 1993).

Therefore, owing to an unchanging anti‑social propensity, some individuals begin their criminal career early and are more likely to maintain their criminal behaviours throughout their life in various forms, which includes intimate partner violence (Gottferdson and Hirschi 1990; Moffitt 1993). Furthermore, with respect to violent behaviours, many authors have shown that violence (experienced and perpetrated) is strongly correlated with the frequent commission of crimes (Farrington 1991; Piquero 2000; Piquero et al. 2007; Piquero et al. 2012). Intimate partner violence does not appear to deviate from this rule (Piquero et al. 2014).

It therefore seems important to consider the connections between criminal career, frequency and variation of crimes when discussing intimate partner violence.

Frequency, variation and recurrence of intimate partner violence

A few authors have placed emphasis on cohabitation and married couples and consider that violence between partners is more likely to be steady among couples where severe intimate partner violence is involved (Caetano et al. 2005; Quigley and Leonard 1996), but also that criminal and anti‑social behaviours in general are correlated with a strong likelihood of persistence in intimate partner violence (Holzworth-Munroe and Stuart 1994). In other words, individuals involved in delinquent behaviours are apparently more likely to commit serious, persistent intimate partner violence over time. For example, in looking at 94 couples in which the husband committed violent acts against the wife during engagement, Lorber and O’Leary (2004) realized that general (non‑domestic) aggression exhibited by the husband is associated with more persistent (severe) intimate partner violence.

In terms of variation of crimes involving intimate partner violence over time, some longitudinal studies suggest that rates of physical violence between partners fall over time (Kim et al. 2008). Shortt et al. (2012) examined (physical and psychological) intimate partner violence among 184 men aged 20 to 30 at risk of offending in Oregon (Oregon Youth Study), paying particular attention to fluctuations in violence over the course of the relationship. They made three important observations: (1) male intimate partner violence decreases with age; (2) physical abuse against a partner in their early 20s predicts abuse in their late 20s; and (3) psychological abuse in their early 20s predicts abuse in their early 30s. In addition, the authors point out greater stability in intimate partner violence among men who remain with the same partner. A few years later, Johnson et al. (2015) studied the commission of intimate partner violence on a sample of 1,200 men and women aged 13 to 28 and noted that acts of violence between partners follow a similar trend to that of the age/criminality curve found for crime in general, even though the commission of intimate partner violence seems to peak a little later (around age 20) and then decline. However, other authors explain that the stability of intimate partner violence over time depends on the severity and frequency of violent acts against the partner. Stability could therefore be observed in the commission of intimate partner violence over time (Greenman and Matsuda 2016), using similar samples followed until around age 30 (Shortt et al. 2012). Feder and Dugan (2002) interviewed abusers and victims of intimate partner violence and showed that violent behaviours do not change over time.

It is worth adding that studies on samples show a higher rate of psychological as opposed to physical intimate partner violence, with similar evidence of stability over time for psychological intimate partner violence (Capaldi et al. 2003; Fritz and Slep 2009; Kim et al. 2008; Shortt et al. 2012). Furthermore, these two types of violence are often related and correlated in the literature, and psychological violence appears to be a precursor to physical assault among couples (Schumacher and Leonard 2005).

In terms of reoffending, most authors agree that perpetrators of intimate partner violence are more likely to repeat this type of crime in their life, even when they change partners. For example, Frantzen, San Miguel and Kwak (2011) report that out of a total of 415 individuals in their sample, 22% of criminals are arrested again for intimate partner violence within two years of their first crime. During the first year of the study, 18% of those convicted for intimate partner violence were arrested again and, after the second year, 24% of those convicted reoffended. As data are collected over a period of two years, and considering what was mentioned earlier, it can be suggested that the numbers increase over the years. A few years earlier, Hilton et al. (2004) had also shown that 30% of the 589 Ontario criminals identified by police for intimate partner violence reoffended after 51 months. It should also be noted that perpetrators of intimate partner violence tend to have a higher rate of reoffending than violent criminals in general. Olson and Stalans (2001) compare samples from each of the two groups and indicate that 18% of perpetrators of intimate partner violence victimize the same individual again during probation, compared to just 5% of perpetrators of other violent crimes.

Intimate partner violence: specialization or generalization in criminality?

The literature explored thus far allows for a better identification of the typical profile of a perpetrator of intimate partner violence. However, one important point must be clarified. As discussed earlier, each individual follows a different criminal path and, despite the fact that many offenders turn to a generalist career (Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990; Laub and Sampson 1993; Piquero, Brame, Mazerolle and Haapanen 2002), the question arises whether perpetrators of intimate partner violence engage in criminality solely in this context or whether their criminal activities, especially violent ones, remain once they have crossed that bridge. Although the aspects discussed up to this point tend to favour an assumption of criminal generalization rather than specialization, it is important to identify specific literature on the subject to determine whether perpetrators of intimate partner violence specialize in this field or whether this form of violence is just a result and projection of other types of crimes committed outside the home.

As a reminder, the empirical literature identified two types of criminals: those who commit offences only in adolescence and those who continue their criminal activities for life (Moffitt 1993). Piquero et al. (2002) add that crimes committed by the first category of individuals are on average not very violent and fairly specialized, while those committed by “lifers” are more varied, and these people are more likely to use violent strategies (Farrington 1991; Piquero 2000; Piquero et al. 2007; Piquero et al. 2012). More specifically, authors favouring a developmental perspective talk about a combination of specialization and generalization in criminal behaviours (DeLisi et al. 2011; Piquero 2000; Piquero et al. 2002) and say that specialization comes with age (Piquero et al. 2003). In other words, crime variety apparently evolves throughout a criminal career: offenders alternate between periods of specialization and generalization with respect to the types of offences committed, and the more a criminal perseveres in the crime, the higher their chances of specializing in a particular crime.

With regard to intimate partner violence, the number of studies that tend to link this type of crime with criminality in general, particularly violent criminality, has increased in recent decades to advance this generalization versus specialization debate. Therefore, some authors who identify the personality traits of perpetrators of intimate partner violence considered the role that aggression and crime play more broadly, notably revealing that individuals who are violent both inside and outside the domestic context tend to engage in more serious intimate partner violence (Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart 1994). Farrington (1994) used CSDD data and found a significant correlation between abusive spouses and criminally violent men (26.2% of the 42 husbands who committed intimate partner violence were convicted for violence). Piquero, Theobald and Farrington (2014) use the same data to explore the overlap between criminal pathways involving general and intimate partner violence as well as the factors associated with such behaviours. Their finding is a significant overlap between criminal violence and intimate partner violence.

These initial results therefore seem to support the specialization theory and the fact that individuals who have a habit of victimizing their partner also tend to have a history of violence against other people as well as of criminal acts in general (Moffitt and Caspi 1999; Feder and Dugen 2002).

To support this, Piquero et al. (2006) explore the cases of 650 individuals who engage in intimate partner violence. The first third of the sample has no criminal history, the second third has a nonviolent criminal history and the final third has a violent criminal history. The results indicate that only a small proportion of the sample specializes solely in violent crimes and that, while some criminals exhibit a high and unchanging degree of aggression, others escalate or de‑escalate in their violent behaviours. Piquero et al. (2006) conclude that perpetrators of domestic violence rarely specialize in domestic violence or even in any violent crime. Verbruggen, Maxwell and Robinson (2020) also examine the connection between trends in delinquency in general and the occurrence and likelihood of persistence of violence between intimate partners in adulthood. To do this, the authors use longitudinal data measured over the course of 18 years on a Chicago cohort (Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods Study). The results identify three groups of general delinquency pathways: (1) no delinquency, (2) low frequency of delinquency and (3) high frequency of delinquency. The individuals involved in delinquency, especially those who exhibit varied delinquency, have an increasing risk of perpetrating serious psychological and physical intimate partner violence, while also exhibiting persistence in the various forms of intimate partner violence. Richards et al. (2012) present a longitudinal study on a cohort of 317 abusers prosecuted for intimate partner violence to determine the pathways of arrest for intimate partner violence and violence outside the intimate context over a period of 10 years. They identify two groups of pathways for arrests for violence between intimate partners (low and high rates) and three pathways for non‑domestic violence (very low, low and high rates). They indicate that specialization among intimate partner abusers is rare and that past crimes related to alcohol and drugs predict falling in the “high rate of arrest for intimate partner violence” category. They also report that a history of intimate partner violence predicts falling in the “high rate” pathways of arrest for non‑domestic violence.

Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994) identify different types of abusers among perpetrators of intimate partner violence. They show that individuals from the group of men who are generally violent/anti‑social (both inside and outside the home) accounted for the highest rate of intimate partner violence over the three‑year study period and were less likely to desist, compared to other groups. Therefore, offenders who are violent against their partners appear to be chronic criminals. Olson and Stalans (2001) compare a sample of individuals on probation for intimate partner violence and another on probation for violent crime. The results they attain differ. First, 52% of the individuals on probation for intimate partner violence were previously convicted as adults (compared to 42% of individuals on probation for violent crime). Second, 63% have previous convictions for violent crime (compared to 54%). Finally, 66% have a history of substance abuse (compared to 48%).

Furthermore, the relationship seems to work in both ways. Richards et al. (2013) followed 317 men convicted for intimate partner violence in Massachusetts over a period of 10 years and report that a history of domestic violence substantially increases the likelihood of violent and nonviolent non‑domestic offences.

With regard to the link between intimate partner violence and reoffending in subsequent crimes, Buzawa and Hirschel (2008) study criminals arrested for intimate partner violence in three U.S. states. They compare individuals without a criminal history, those without a violent history and those with a violent history. They discovered that individuals from groups with a violent or (non‑violent) criminal history are more likely to be arrested again for any offence in the three to five years that follow. It is also interesting to note that in studying 730 individuals with a record of intimate partner violence, Bouffard and Zedaker (2016) point to the probability that women have a higher degree of specialization than men in terms of intimate partner violence.

An important fact to note is that most of the studies presented are based on self‑reported data. However, a few studies using official data also show that a large proportion of offenders arrested for intimate partner violence also have a history of delinquency in general (Buzawa and Hirschel 2008; Hilton and Eke 2016; Klein and Tobin 2008; Piquero et al. 2006).

All of the studies examined here, conducted all around the world, show a significant overlap between general crimes and intimate partner violence. These aspects support the notion of generalization of crimes against a spouse among violent criminals and stress the importance of considering the criminal history of perpetrators of intimate partner violence. It can therefore be suggested that domestic violence is but a manifestation of a variety of criminal behaviours (Piquero et al. 2006). Also, violence in crimes and intimate partner violence are intricately linked and strongly predicted by chronic crime (Piquero, Theobald and Farrington 2014). Intimate partner violence is often part of a broader set of anti‑social behaviours. Intervention must therefore focus on interrupting the criminal career of young offenders to reduce the prevalence and commission of violence between partners (Verbruggen et al. 2020).

The situation in Canada

In Canada, very few studies aim to connect the generalization of types of crimes and intimate partner violence. A few Canadian preliminary research studies have been undertaken, but must be supplemented for a better understanding of the phenomenon.

In Ontario, Hilton et al. (2004) designed a scale to predict repeat violence against a current or former intimate partner (Ontario Domestic Assault Risk Assessment, ODARA). They studied a sample of 589 criminals identified by police for intimate partner violence over five years. They found that: (1) 24% of criminals in their sample had previous correctional sentences; (2) 4% have a history of violence against someone other than a partner; (3) 15% violated parole; and (4) 100% had already injured someone in the course of a violent crime. In continuity with this study, Hilton and Eke (2016) analyzed the general offences of 93 perpetrators of intimate partner violence to predict reoffending 7.5 years later. The authors concluded that most men arrested for intimate partner violence do not specialize in their criminal career. Therefore, the risk assessment could include not only risks of behaviours involving intimate partner violence, but also risks of other offences.

In Quebec, Ouellet et al. (2016) looked at a total of 52,149 incidents of intimate partner violence recorded by police and show that 31% of these incidents involve a suspect with a criminal record for non‑domestic criminality only. The study results also report that perpetrators of intimate partner violence with a criminal record have a 16% greater chance of being involved in more serious domestic incidents. This study therefore provides an empirical basis on which to suggest that so‑called “generalist” criminals, known to police, have a significant impact on the proportion of incidents of intimate partner violence, particularly the most serious incidents.

These pioneering results tend towards a generalization of violence among perpetrators of intimate partner violence, as shown by empirical studies conducted in other countries. However, the lack of Canadian research on the topic prevents confirmation of such a finding.

A number of shortcomings can be identified in studies tending to link a criminal career with intimate partner violence. While the scientific literature confirms that individuals who are violent towards their (former) spouse tend to commit a variety of crimes, there is little empirical evidence that these individuals centre their criminal careers on violence causing bodily harm outside the home. To determine whether long‑standing assumptions on specialization and escalation of violence among domestic violence offenders are accurate, we must examine the pathways of arrest for intimate partner violence. To date, very little Canadian research of this type exists. Also, few longitudinal studies on intimate partner violence consider the frequency of violence over time.

In addition, a small amount of research explores the relationship between developmental models of general delinquency and the development of commission of intimate partner violence. Although criminality in general is a risk factor for the perpetration of intimate partner violence (Capaldi et al. 2012; Costa et al. 2015), relatively little is known about the various general delinquent behaviours tied to the commission of intimate partner violence in developmental models. This is largely due to the fact that researchers working on intimate partner violence develop their model separately from general delinquency theories. Piquero et al. (2014) state that specific, less visible crimes such as intimate partner violence are rarely included in general delinquency models.

Lastly, psychological intimate partner violence is less studied in the literature than physical intimate partner violence. However, it is important to consider it. It is also worth noting that research on the association between general criminality and psychological intimate partner violence is limited. Some evidence does nevertheless exist as to the involvement of anti‑social behavior linked to an increase in the likelihood of commission of psychological intimate partner violence (Kim et al. 2008; Magdol et al. 1998).

Research objectives

This literature review reveals that studies on criminal careers conducted in a number of countries show that many offenders involved in intimate partner violence do not specialize solely in this type of offence. Some empirical literature demonstrates that offenders committing serious and frequent assaults in an intimate context are also more likely to engage in other types of violent and criminal behaviours. These individuals are known for committing a number of more serious crimes, meaning that they require sustained intervention and mobilize more resources. There is therefore a real interest in identifying these individuals.

Few Canadian studies establish a connection between intimate partner violence and other types of violent crimes, and therein lies the question inherent to this research project: Are individuals convicted of intimate partner violence in Canada also involved in other types of violent and criminal behaviours outside the family, specifically violent crimes with the potential for causing someone bodily harm?

The main objective of this research is to create a profile of the official and self‑reported criminal career of individuals convicted of intimate partner violence by observing their behaviours in relation to intimate partner violence, as well as their violent behaviours and other crimes committed by them. The specific objectives are as follows:

- Examine the proportion of offenders in each group (1- intimate partner violence only, 2- intimate partner violence and other violent behaviours, 3- intimate partner violence and other crimes, 4- intimate partner violence, other violent behaviours and other crimes);

- For the various groups of offenders, determine for each crime category (intimate partner violence, other violent behaviours, other crimes) the age at first crime, the nature of the offences, criminal diversification and frequency of crimes committed;

- Examine the individual characteristics distinguishing the various offender groups (such as gender, visible minority, status in Canada, income, place of residence) and examine the predictive value of these characteristics on the perpetration of serious violence.

Methodology

The purpose of this section of the report is to present the methodology behind the study to take stock of and justify some of the methodological choices. Covered are the data source, the procedure followed and the instruments used to compile the analyzed information. A brief overview of the offenders under study is then presented. Lastly, the analysis strategy and certain methodological limitations are outlined.

Data source

To meet the objectives of this report, analyses were carried out on data from another research project. For this first project, 121 incarcerated violent spouses (with provincial sentences) were interviewed between 2018 and 2020. A violent spouse is defined as a man 18 years of age or older who has been convicted for violent offences against his wife or ex‑wife. This project focused mainly on offenders involved in intimate partner violence and sought to thoroughly analyze the criminal pathways of and the processes leading to offending among offenders who committed intimate partner violence.

Six provincial correctional institutions in Quebec (sentences of less than two years) were solicited and participated in recruiting offenders. Correctional officers at the prisons visited first approached the offenders to ask if they would participate in the research project. These offenders had to be incarcerated for an offence committed in an intimate context. The participants were selected by the research teach based on a diversification criterion, that is, sentence length, age and nature of relationship to victim (spouse, former spouse). In each institution, a meeting was arranged with the selected offenders who had volunteered. During this meeting, team members explained the details of participation in this project, after which the offenders were asked to give their consent to participate in the research (which includes interviews and consultation of the official record). It is important to point out that this research project, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (Insight program; principal investigator – Jean Proulx) was approved by the Comité d’éthique de la recherche - Société et culture (CER-SC) at Université de Montréal. The questionnaires were administered by qualified interviewers (primarily Master’s students from the School of Criminology at Université de Montréal). Each of the 121 violent spouses therefore took part in a structured one-on-one interview, based on which the offender’s criminal pathway could be reconstructed. Official records were also consulted to complete some information in the questionnaire used. Moreover, each participant completed a series of psychometric instruments designed to evaluate his personal traits and relationship.

Instruments and procedures

This report is essentially based on data compiled during structured interviews on the criminal pathway. The two-part questionnaire was administered face to face, which took two hours and ten minutes on average. In the first part of the questionnaire, the information collected pertained to the participants’ individual traits: socio‑demographic and family data, psychological and physical limitations, life events (such as a history of violence perpetrated and experienced in life), opinions and attitudes about various topics (such as sense of security, judicial system, violence and responsibility). It is in this part of the questionnaire that official records on criminal history were used to complete the information on past arrests and convictions. The second part of the questionnaire focuses on the criminal pathway and violence in a relationship in the 36 months preceding the current term of incarceration as well as the accompanying life circumstances. The data were collected using the life history calendar method. This method provides detailed short-term data, for example, on a monthly or annual basis, and has proven reliable (Sutton et al. 2011). It improves the quality of retrospective data, particularly with the synchronization of events and changes that may arise in individual pathways (Freedman, Thornton, Camburn, Alwin and Young-DeMarco 1988). The data collection structure using this method is adapted to the participants’ autobiographical memory structure (Belli 1998). Themes addressed include: criminal pathway, incidents of (physical, psychological and sexual) intimate partner violence, significant events (such as job loss, death of a loved one, separation, illness, financial loss), conventional circumstances (such as employment), how participants handled these events (in terms of cognition, emotion and behaviour), social capital (such as friends and family), (alcohol, drug and medication) consumption and problems with the justice system unrelated to intimate partner violence.

Crimes perpetrated

This report looks at the context in which crimes were committed. More specifically, a distinction is made between crimes committed in an intimate context and those perpetrated outside that context. Attention is also paid to crimes with the potential to cause bodily harm. The definition used in this report is taken from the Criminal Code of Canada: “any hurt or injury to a person that interferes with the health or comfort of the person and that is more than merely transient or trifling in nature (lésions corporelles)” (Criminal Code, R.S.C., 1985, c. C‑46). The injury can therefore be of varying nature, but must not be merely transient or trifling to be considered bodily harm. Therefore, acts of verbal violence (such as some forms of psychological or emotional violence through words or actions inside or outside the family intended to control, isolate, intimidate or dehumanize) or acts of economic violence (such as financial exploitation inside or outside the family) likely to cause psychological or physical harm can be considered bodily harm, if the injury is neither transient nor trifling. This definition of bodily harm, therefore, covers all forms of (physical, psychological, financial and sexual) domestic violence and does not apply to just the family environment; such violence can also be perpetrated outside the family. Two types of data are used to measure the offences committed. Official long- and short-term data were taken from inmate records kept by penitentiary authorities. These data were consulted to supplement the information on the arrests and convictions of the offenders interviewed. Information on self‑reported criminality was compiled during structured interviews. The life history calendar method was used to collect this information for the study period.

Intimate partner violence

The instrument used to measure intimate partner violence perpetrated in an intimate context on a monthly basis is inspired by the revised version of the Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2) developed by Straus (1996) and translated by Lussier (1997). The instrument consists of five subscales: negotiation, psychological violence, physical assault, sexual violence and injury. Each of these subscales contains items on minor or severe violence.

Crime outside the intimate context

Crimes committed outside the intimate context are divided into two spheres of activity: violent crimes and other crimes.

First, violent crimes refer to: common assault, assault with a weapon or causing bodily harm, threats or extortion, sexual assault, homicide, and other violent crimes. It is important to note that all of these forms of criminality are likely to lead to bodily harm.

Other crimes entail for-profit crimes, such as crimes of acquisition (robbery, break‑in, motor vehicle theft, theft, fraud, business fraud) and market-based crimes (drug sale and distribution, contraband, loan‑sharking, illegal betting, sex trade, possession of stolen property and other market-based crime).

Description of participants

The offenders interviewed are all male and were on average 38.6 years of age at the time of the interview. They largely considered themselves to be Canadian (86.8%). The education level is fairly low: more than half (57.0%) of participants had not finished high school. Close to 63% of the men interviewed were already fathers at the time of the interview. It should also be noted that during the study period, 35.5% of the offenders had a wife who was pregnant, 39.7% revealed that they had had mental health problems and 22.3% had physical limitations.Footnote 1

Table 1 also shows certain risk factors in childhood and adolescence. Many participants are therefore observed to come from family environments with certain problems. Most grew up in an environment where at least one of the two parents had alcohol problems. Drug problems (28.9%) and criminal history (30.6%) among parents are also events that marked the childhood or adolescence of many of the participants interviewed. In addition, it should be noted that close to half of the offenders were reported to the Director of Youth Protection (DYP).

With regard to exposure to intimate partner violence during childhood or adolescence, half of offenders witnessed psychological violence between their parents (or step-parents) and more than one in five offenders were exposed to physical violence between parents.

| Individual Characteristics | Mean (SD) / % |

|---|---|

| Participant age | 38.6 years (10.2) |

| Ethnic origin | |

| Canadian | 86.8% |

| Non-Canadian | 13.2% |

| Education level | |

| Finished high school | 43.0% |

| Did not finish high school | 57.0% |

| Children (yes/no) | 62.8% |

| Wife pregnant during study period (yes/no) | 35.5% |

| Daily activities limited by psychological, emotional or mental state (study period; yes/no) | 39.7% |

| Daily activities limited by physical problem (study period; yes/no) | 22.3% |

| Risk factors in childhood/adolescence | Mean (SD) / % |

|---|---|

| Parent(s) with alcohol problem (yes/no) | 51.2% |

| Parent(s) with drug problem (yes/no) | 28.9% |

| Parent(s) with criminal history (yes/no) | 30.6% |

| Reported to DYP in childhood/adolescence (yes/no) | 49.6% |

| Exposure to intimate partner violence in childhood/adolescence | Mean (SD) / % |

|---|---|

| Witnessed psychological violence between own parents (yes/no) | 50.4% |

| Witnessed physical assault between own parents (yes/no) | 24.0% |

Abbreviations used in this table

SD: standard deviation

DYP: Director of Youth Protection

Analysis strategies

The type of analyses used progresses gradually in this report. The analyses of Objective A are essentially descriptive. The analyses carried out as part of Objective B combine both descriptive and bivariate analyses. Lastly, multivariate analyses were used to meet Objective C. All analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 25.0.

Descriptive analyses

Descriptive analyses are essentially used to describe a fairly significant data set. These analyses, which involve numerous techniques (such as mean), will be used to describe not only criminal participation (Objective A), but also the various criminal career parameters, including intimate partner violence parameters (Objective B).

Bivariate analyses

The aim in Objective B is to determine whether there are differences in criminal career parameters between various groups of offenders. Bivariate analyses involve analyzing two variables to determine the empirical relationship between them. Mean and chi‑square tests were carried out to determine whether the differences observed between offender groups are statistically significant.

Multivariate analyses

Multivariate analyses focus on the predictive value of multiple variables simultaneously. To predict certain violent or serious behaviours, both inside and outside an intimate context, (linear and logistic) regressions are conducted to separate the predictive value of individual characteristics and intimate partner violence and criminal career parameters. Regression models are built to predict the variance of a phenomenon (dependent variable) using a combination of explanatory factors (independent variables).

Results

As a reminder, the main purpose of this report is to use Canadian data to demonstrate whether offenders involved in intimate partner violence also engage in other forms of criminality. The first part of this report describes the criminal participation of offenders incarcerated for crimes committed in an intimate context at the time of the interview (Objective A). Criminal participation is examined over the span of an entire criminal career as well as over a time window corresponding to three years prior to the start of their current term of incarceration (the study period). The second part of this report aims to examine criminal career parameters (Objective B), for example, age at first crime, the nature of the offences committed, criminal diversification and crime frequency. Intimate partner violence, its forms and its intensity will be described. Special attention is also paid to the nature of the crimes committed. This review serves to identify, whenever possible, participants’ involvement in domestic violence or in violent crimes with the potential for bodily harm against someone. With regard to the results obtained, the final part of the report aims to determine whether it is possible to predict which offenders commit serious and frequent assaults both inside and outside an intimate context (Objective C).

Objective A

This part of the research report seeks to examine the criminal participation of the perpetrators of intimate partner violence interviewed. The objective is to observe the proportion of offenders who are involved in various spheres of criminal activity. Before undertaking the conceptualization of criminal participation, it is important to reiterate that all participants were serving a prison sentence for intimate partner violence at the time. In other words, all participants engaged in intimate partner violence. Criminal participation is therefore observed in three broad crime categories: intimate partner violence, violent crimes and other crimes. The participants were therefore divided into four groups: the first group consists of individuals engaged solely in intimate partner violence; the second, individuals who participated in intimate partner violence and violent crimes; the third, individuals who committed intimate partner violence and other crimes; and the fourth, individuals who participated in intimate partner violence, violent crimes and other crimes (Group 4). For this descriptive review, two types of data are used (self‑reported and official) as well as two time perspectives (long- and short-term). These different angles of analysis allow for a comparison of the criminal participation profiles obtained, but more specifically a review of the criminal pathway beyond official records. Many studies show that criminal history is an excellent predictor of future criminal behaviour (re-arrest, Freeman 2007; Lattimore et al. 1995). What is therefore proposed here is an observation of self‑reported criminal participation that does not show up in official data, which makes it possible to judge the reliability of certain official data.

Criminal participation over the span of an entire criminal career

First, criminal participation profiles are compared over the span of an entire criminal career. Figure 1 presents the proportion of offenders included in each of the four groups created. It is clear that criminal specialization is rare when considering the criminal pathway as a whole. Individuals who have participated in at least two broad crime categories account for 94.3% of the sample. In addition, the majority (71.1%) reveal involvement in all crime categories. Participants who engaged only in intimate partner violence during their criminal pathway account for just 5.8% of the individuals interviewed.

Text version: Self reported criminal participation over the span of an entire criminal career

5.8% intimate partner violence only; 2.5% intimate partner violence and violent crime; 20.7% intimate partner violence and other crime; 71.1% intimate partner, violent crime and other crime.

This criminal participation profile, based on self‑reported data, shows that the offenders interviewed are more generalists when their entire criminal career is considered. What remains now is to make the same comparison, but with a different data source. More specifically, it is interesting to compare this self‑reported criminal participation profile against the profile obtained from official criminal histories, that is, crimes for which the participants have served a prison term.

For information purposes, the offenders interviewed have had, on average, four separate incarceration episodes. The reasons for past incarceration provide a very different picture of criminal participation (Figure 2). It is important to note that the review of criminal participation based on these official data required the creation of four additional categories. Although the offenders interviewed were serving a sentence for violence committed in an intimate context, it remains possible that their official histories do not reveal involvement in this type of crime (or any criminal participation) because the data exclude the current episode of incarceration. Based on official data, it is therefore possible that these individuals, in addition to the four categories already mentioned, had criminal involvement limited to violent crimes or other crimes or both violent and other crimes, excluding intimate partner violence. It is also possible that the criminal record shows no history of incarceration.

The self‑reported data on participation showed great criminal versatility, which is not the case when looking at official data. While the majority of participants reported having committed all three categories of crime during their criminal career (71.1%), this proportion is much lower (7.4%) when the reason for incarceration comes into play. Furthermore, according to this same data source, many offenders present criminal specialization (40.5%) over the span of their entire criminal career. In many cases, a history of violence (36.3%) or intimate partner violence (71.9%) does not show up in official records for previous convictions, whereas in self‑reported data, nearly all participants committed violent crimes (94.2%) and intimate partner violence (100%) over the span of their entire criminal career.

Text version: Official criminal participation over the span of an entire criminal career

6.6% intimate partner violence only; 5.0% intimate partner violence and violent crime; 9.1% intimate partner violence and other crime; 7.4% intimate partner violence, violent crime and other crime; 14.1% violent crime only; 19.8% other crime only; 21.5% violent crime and other crime; 16.5% no incarceration.

The criminal participation profile is therefore very different depending on the data source used. While the offenders interviewed admit to having been involved in multiple types of crimes, the reasons for past convictions show a whole other reality, a more nuanced profile highlighting a stronger specialization trend. In light of the results obtained, it can be confirmed that official data largely underestimate criminal participation, particularly in terms of intimate partner violence.

Criminal participation in the three years preceding the current term of incarceration

Criminal participation in the three years preceding the current term of incarceration at the time of the interviews is examined next. This examination looks at the recent criminality of the individuals interviewed. Works on criminal careers show that age of initiation and involvement differ depending on the type of crime (Le Blanc and Bouthillier 2003). For example, some types of crimes (such as vandalism) manifest to a greater extend during adolescence and are abandoned by most offenders when they enter adulthood. In criminology, the significance of the relationship between past and future criminal activities is recognized (Piquero et al. 2003), and this relationship is all the stronger when recent criminal behaviours are used to predict future criminal involvement. Some studies tend to demonstrate that after some time has passed without the transition to offending, the association between the presence of a criminal record and recidivism loses its predictive power (Blumstein and Nakamura 2009). Thus, criminal participation taken from a short-term perspective is relevant notably in the prediction of continuity in criminal activity. It is also of interest in terms of intervention with offenders.

An observation made regarding self‑reported criminal participation in the three years preceding the current term of incarceration is that it is distributed among the four categories (Figure 3). The proportion of individuals reporting specialization in intimate partner violence (26.4%) or violent crimes (19.8%) accounts for close to half the sample (46.2%). These proportions are much higher than those observed with the same type of data, but over the span of an entire criminal career (5.8% and 2.5%, respectively). It remains that many individuals are involved in both intimate partner violence and other crimes (21.5%). It is also important to point out that the category representing involvement in the three spheres of criminality is the largest (32.2%).

Text version: Self reported criminal participation in the three years preceding the current term of incarceration

26.4% intimate partner violence only; 19.8% intimate partner violence and violent crime; 21.5% intimate partner violence and other crime; 32.2% intimate partner violence, violent crime and other crime.

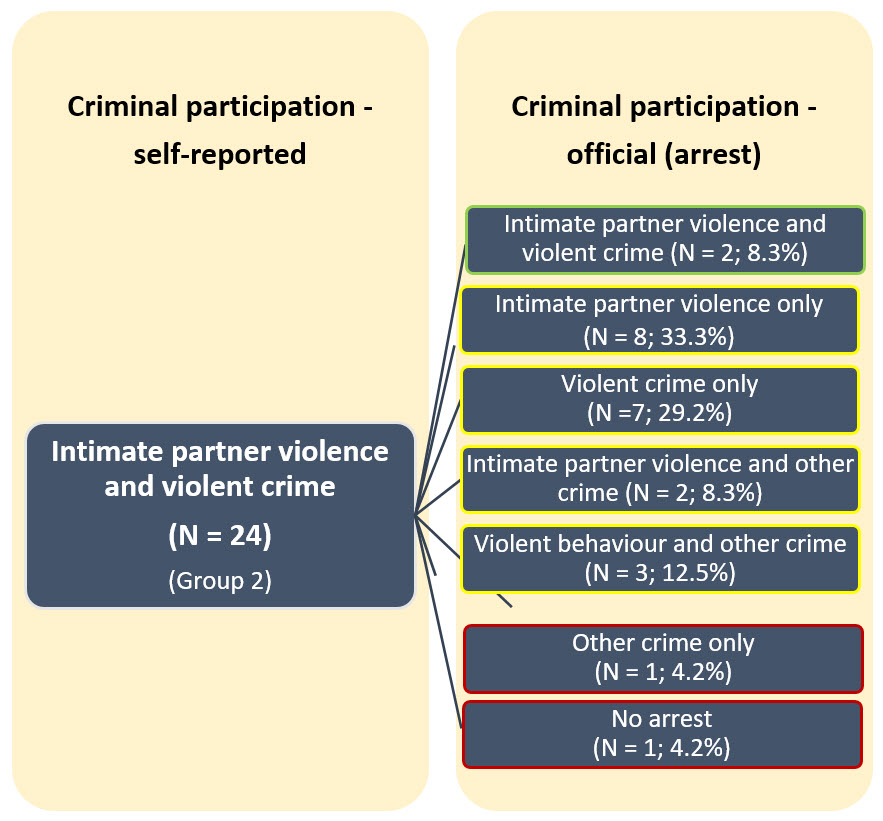

The specialization trend would therefore be stronger inside a smaller time window, but the fact remains that most individuals participate in various spheres of criminal activity. As in the previous section, the criminal participation profile should be examined based on official data.