Health impacts of traffic-related air pollution in Canada

Download in PDF format

(4,310 KB, 93 pages)

Organization: Health Canada

Date published: March 2022

Cat.: H144-91/2022E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-40966-5

Pub.: 210436

March 2022

Table of contents

- List of tables

- List of figures

- List of abbreviations

- Executive summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Methodology

- 3. Results

- 4. Discussion

- 5. Conclusion

- 6. References

- 7. Appendices

List of tables

- Table 1. Air pollutant emissions in Canada, in tonnes, for the year 2015 – Source categories and classes, and transportation sub-classes

- Table 2. Percentage of provincial and territorial emissions from on-road transport in 2015

- Table 3. Contributions from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to ambient PM2.5 concentrations in 2015 – Provincial, territorial, and national estimates – Population-weighted annual average

- Table 4. Contributions from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to ambient PM2.5 concentrations in 2015 – CDs with the highest net contributions – Area-weighted annual average

- Table 5. Contributions from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to ambient NO2 concentrations in 2015 – Provincial, territorial, and national estimates – Population-weighted annual average

- Table 6. Contributions from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to ambient NO2 concentrations in 2015 – CDs with the highest net contributions – Area-weighted annual average

- Table 7. Contribution from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to ambient summer O3 concentrations in 2015 – Provincial, territorial, and national estimates – Population-weighted summer average of daily maximum values

- Table 8. Contribution from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to summer O3 concentrations in 2015 – CDs with the highest net contributions – Area-weighted summer average of daily maximum values

- Table 9. Contribution from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to ambient annual O3 concentrations in 2015 – Provincial, territorial, and national estimates – Population-weighted annual average of daily maximum values

- Table 10. Contribution from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to ambient annual O3 concentrations in 2015 – CDs with the highest net contributions – Area-weighted annual average of daily maximum values

- Table 11. Contribution from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to ambient annual O3 concentrations in 2015 – CDs with negative estimates – Area-weighted annual average of daily maximum values

- Table 12. Contributions from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to ambient SO2 concentrations in 2015 – Provincial, territorial, and national estimates – Population-weighted annual average

- Table 13. National estimates of premature deaths and non-fatal health outcomes associated with exposure to TRAP from Canadian sources in 2015, by health endpoint – Counts and valuation

- Table 14. Premature deaths associated with exposure to TRAP in 2015, by pollutant – Provincial and national estimates – Counts and rates per 100,000 population

- Table 15. Premature deaths associated with exposure to TRAP from Canadian sources in 2015, by pollutant – Census divisions with the highest estimates – Counts and rates per 100,000 population

- Table 16. Contributions from on-road vehicle emissions to ambient concentrations of NO2, O3 and PM2.5 in 2015 – Provincial and territorial population-weighted averages and maximum area-weighted CD estimates

- Table 17. Contributions from Canadian on-road gasoline vehicle emissions, on-road diesel vehicle emissions, and TRAP to ambient PM2.5 concentrations in 2015 – Provincial and national estimates – Population-weighted annual average

- Table 18. Contributions from Canadian on-road gasoline vehicle emissions, on-road diesel vehicle emissions, and TRAP to ambient NO2 concentrations in 2015 – Provincial and national estimates – Population-weighted annual average

- Table 19. Contributions from on-road gasoline vehicle emissions, on-road diesel vehicle emissions and TRAP to summer average ambient 1-hour maximum O3 concentrations in 2015 – Provincial and national estimates – Population-weighted annual average

- Table 20. Premature death associated with Canadian on-road gasoline vehicle emissions, on-road diesel vehicle emissions and all on-road vehicle emissions using various CRFs for PM2.5 chronic exposure mortality – National estimates for calendar year 2015

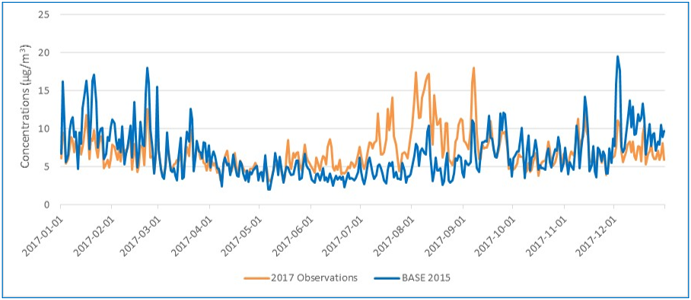

- Table 21. Annual performance evaluation statistics comparing the 2015 base case estimates in GEM-MACH and 2017 observations

List of figures

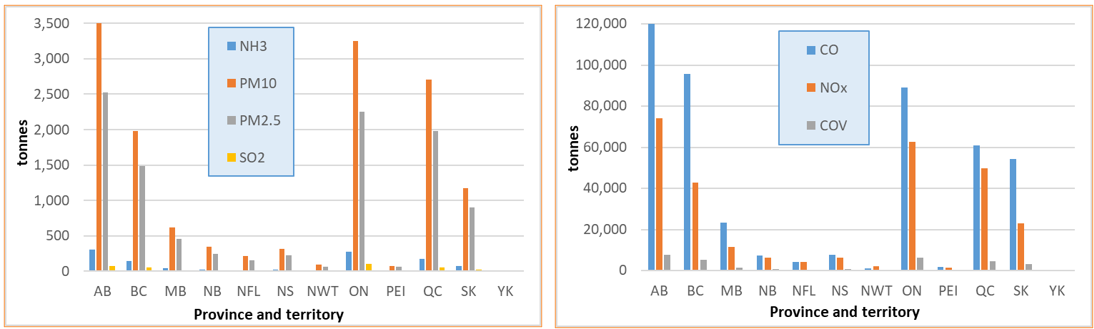

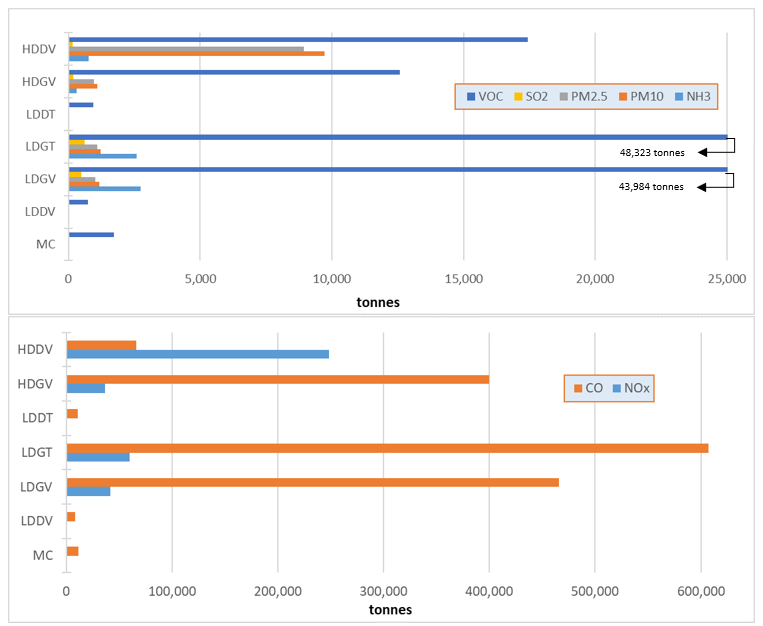

- Figure 1. On-road heavy-duty (HDV) and light-duty (LDV) vehicle emissions in Canada, based on the 2015 inventory

- Figure 2. Heavy-duty vehicle emissions in the 2015 Canadian emissions inventory

- Figure 3. Light-duty vehicle emissions in the 2015 Canadian emissions inventory

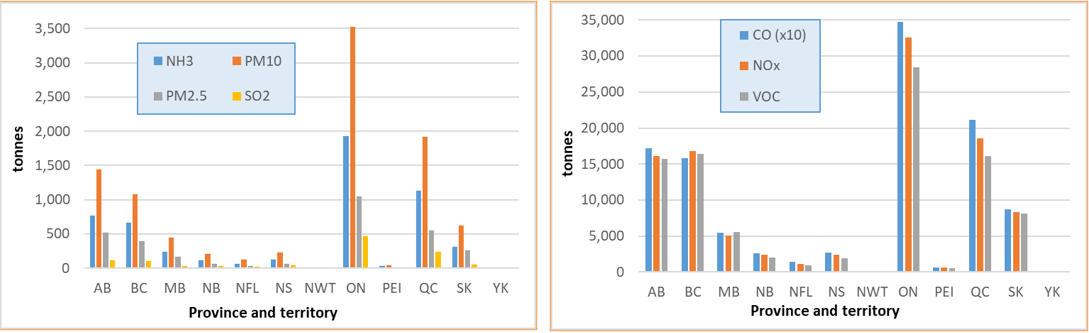

- Figure 4. Net contribution (µg/m3) from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to annual average PM2.5 concentrations in 2015

- Figure 5. Net contribution (ppbv) from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to annual average NO2 concentrations in 2015

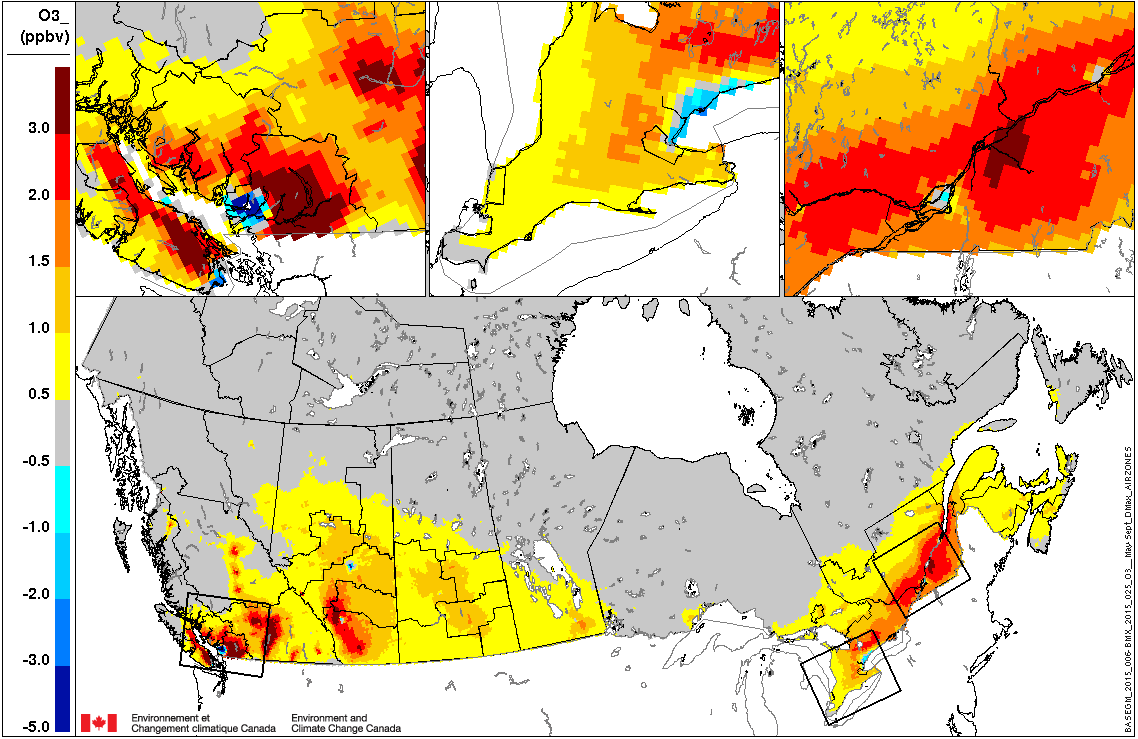

- Figure 6. Net contribution (ppbv) from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to summer average daily maximum O3 concentrations in 2015

- Figure 7. Net contribution (ppbv) from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to annual average daily maximum O3 concentrations in 2015

List of abbreviations

- ADOM

- Acid Deposition Oxidant Model

- APEI

- Air Pollutant Emissions Inventory

- AQBAT

- Air Quality Benefits Assessment Tool

- AURAMS

- A Unified Regional Air Quality Modelling System

- CAD

- Canadian dollar

- CD

- Census division

- CM

- Crustal material

- CO

- Carbon monoxide

- COPD

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CRF

- Concentration response function

- CTM

- Chemical transport model

- EC

- Elemental carbon

- ECCC

- Environment and Climate Change Canada

- GEM

- Global Environmental Multiscale (weather forecast model)

- GEM-MACH

- Global Environmental Multiscale – Modelling Air Quality & Chemistry

- GIS

- Geographic information system

- GTHA

- Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area

- HDV

- Heavy-duty vehicle

- HDV8

- Class 8 heavy-duty vehicle

- HEI

- Health Effects Institute

- HPC

- High Performance Computing

- IHD

- Ischemic heart disease

- IHME

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation

- LDDT

- Light-duty diesel truck

- LDT

- Light-duty truck

- LDV

- Light-duty vehicle

- µg/m3

- Micrograms per cubic metre

- MBE

- Mean bias error

- MOVES

- Motor Vehicle Emission Simulator

- NH3

- Ammonia

- NO2

- Nitrogen dioxide

- NO3

- Ammonium

- O3

- Ozone

- PM2.5

- Fine particulate matter

- POA

- Primary organic aerosol

- ppb

- Part per billion by volume

- ppm

- Part per million

- RMSE

- Root mean square error

- SMOKE

- Sparse Matrix Operator Kernel Emissions

- SO2

- Sulphur dioxide

- SOA

- Secondary organic aerosol

- TRAP

- Traffic-related air pollution

- TWBL

- Tire wear and brake lining

- US EPA

- United States Environmental Protection Agency

- VAQUM

- Verification of Air Quality Models

- VOC

- Volatile organic compound

- WHO

- World Health Organization

- WTP

- Willingness to pay

Executive summary

A large body of scientific evidence has accumulated over the past 25 years attributing a wide range of adverse health effects to ambient (outdoor) air pollution exposure. These effects range in severity from respiratory symptoms to the development of disease and premature death. For example, exposure to airborne particles, a component of smog, increases the risk of premature mortality from heart disease, stroke and lung cancer.

On-road vehicles contribute to air pollution through fuel combustion and evaporative emissions as well as emissions from tire and brake wear. Canadians are regularly exposed to traffic-related air pollution (TRAP), most notably in high-traffic areas such as near highways and urban centres. TRAP consists of a complex and variable mixture of particulate and gaseous pollutants that contribute to smog, including fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and ozone (O3).

The objective of this report is to present modelled estimates of population health impacts and socio-economic costs associated with exposure to TRAP in Canada for the year 2015, specifically the contribution from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to PM2.5, NO2 and O3 ambient concentrations in Canada. The year 2015 was selected for modelling based on data availability and quality considerations. Results at the national, provincial and territorial, and census division level are presented and discussed. The report is intended to inform Canadian authorities on the air quality and health impacts associated with on-road vehicle activity.

This report estimates that TRAP was associated with over 1,200 premature deaths in Canada in 2015. Of these, it was estimated that exposure to PM2.5, NO2 and O3 contributed to 800, 340 and 85 premature deaths, respectively. Non-fatal health outcomes included 2.7 million acute respiratory symptom days, 1.1 million restricted activity days and 210,000 asthma symptom days per year. The total annual monetary value of the health burden was estimated at $9.5 billion (CAD 2015), with $9 billion being associated with premature deaths. Analysis also found that light-duty vehicles (e.g. passenger vehicles) contributed to approximately 37% of premature deaths, while heavy-duty vehicles (e.g. commercial trucks and buses) contributed to approximately 63% of premature deaths. In terms of the geographic distribution of the air pollution burden, the results indicated greater adverse health impacts in more populous provinces and census divisions (CDs): 500 premature deaths were estimated in Ontario, 410 in Quebec, 170 in British Columbia and 82 in Alberta. At the CD level, 170 premature deaths were estimated in Toronto, 150 in Montreal, and 110 in Vancouver. The results from this analysis are available for all CDs and can be obtained upon request from Health Canada.

The air quality modelling for this analysis was conducted at a grid resolution of 10 km, which is a reasonably high resolution for a national assessment. However, 10-km grid cells are too coarse to capture the local variability and magnitude in exposures to TRAP, such as those experienced by populations near high-traffic roadways. This limitation likely leads to an underestimation of population exposure to TRAP and health impacts, so that the values herein possibly represent a lower range estimate.

This analysis contributes to our understanding of the health burden of exposure to TRAP in Canada. It also complements recent and ongoing activities on TRAP at Health Canada, including health risk assessments and an evaluation of exposure to TRAP in Canada. Together, these analyses are intended to provide a comprehensive national evaluation of TRAP in Canada.

1. Introduction

A large body of scientific evidence has accumulated over the past 25 years attributing a wide range of adverse health effects to ambient (outdoor) air pollution exposure. These effects range in severity from respiratory symptoms to the development of disease and premature death. For example, exposure to airborne particles, a component of smog, increases the risk of premature mortality from heart disease, stroke and lung cancer. In Canada and internationally, health impact assessments identify air pollution as one of the top risk factors for premature mortality and several non-fatal outcomes (WHO 2016). Exposure to air pollution is currently considered the fifth leading mortality health risk in the world and, in 2017, was responsible for 4.9 million premature mortalities, or 8.7% of all deaths globally (IHME and HEI 2019). Burnett et al. (2018) attributed 8.9 million deaths in 2015 to exposure to ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) alone.

Health Canada estimated that 15,300 premature deaths in Canada were associated with ambient air pollution exposure in 2016 (Health Canada 2021). For their analysis, Health Canada defined air pollution as the above-background increment of ambient PM2.5, nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and ozone (O3) concentrations that can be attributed to anthropogenic North American sources of emissions (e.g., fuel combustion, industry, etc.), as well as emissions from natural events such as wildfires. Non-fatal outcomes were also estimated, including 2.7 million asthma symptom days per year and 35 million acute respiratory symptom days, with the total economic cost of all health impacts attributable to air pollution in 2016 Canadian dollars (CAD 2016) being $120 billion (Health Canada 2021).

The contribution from on-road vehicles to ambient air pollution is referred to as traffic-related air pollution (TRAP). Most Canadians experience exposure to TRAP on a daily basis, particularly in high-traffic areas such as near highways and in urban centres (Brauer et al. 2012, 2013; Matz et al. 2018). TRAP consists of a mixture of particulate and gaseous pollutants associated with combustion (i.e. vehicle exhaust) and non-combustion (e.g. fuel evaporation, abrasion wear) processes. TRAP can influence ambient concentrations of several air pollutants, including PM2.5 and O3 that are responsible for smog. Owing to its complex and variable composition, the TRAP mixture cannot be measured directly. It is generally estimated using a limited number of measurable surrogates, such as NO2 or ultrafine particulate matter, which involves some uncertainties.

The objective of this report is to present estimates of population health impacts and costs associated with exposure to TRAP in Canada. The results are intended to inform Canadians and provincial, territorial and regional stakeholders of the air quality and health impacts associated with on-road vehicle activity. This analysis focuses on the contribution of Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to ambient concentrations of PM2.5, NO2, O3 and sulphur dioxide (SO2) for the year 2015, and the associated health impacts for PM2.5, NO2 and O3, including premature death and morbidity, in Canada. Traffic is defined as on-road transportation and corresponds to the category on-road vehicles in Canada's Air Pollutant Emissions Inventory (APEI). These include light-duty vehicles and trucks, motorcycles, buses, and medium-duty and heavy-duty vehicles. Vehicles used for off-road applications, such as agricultural and mining equipment, are excluded from the on-road category. Health Canada collaborated with Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) to estimate the ambient air pollution attributable to TRAP across Canada, interpreted herein as the exposure to TRAP. To estimate exposure, the Global Environmental Multiscale – Modelling Air Quality and Chemistry (GEM-MACH) model was used. The air quality modelling for this analysis was conducted at a grid resolution of 10 km. The air quality modelling results were then averaged over Canadian census divisions (CDs), which vary in size. The modelling approach and regional resolution were selected for this national assessment. It does not capture the local variability and magnitude in exposures to TRAP, such as those experienced by populations near high-traffic roadways.

Health Canada used the output from the air quality modelling to estimate TRAP population health impacts as well as the monetary value of the related health burden across Canada using the Air Quality Benefits Assessment Tool (AQBAT). This modelling-based analysis considered exposure to ambient levels of PM2.5, O3 and NO2. Air quality and health impacts associated with other toxic air pollutants in TRAP, including SO2, carbon monoxide (CO), organic compounds (e.g. volatile organic compounds such as formaldehyde and benzene, polycyclic aromatic compounds), ultrafine particulate matter (UFP) or specific PM2.5-associated compounds (e.g., metals, polycyclic aromatic compounds), were not included. The health impact assessment provides results at the national, provincial, territorial and census division levels. As such, the health impact estimates reflect average regional air pollution exposures rather than local or high pollution microenvironment exposures, such as in near-road environments.

The current analysis complements and updates previous health impact analyses for diesel- and gasoline-related air pollution published by Health Canada (2016a, 2017). It uses updated data and modelling tools to investigate the health impacts of all on-road sources and fuel types. The analysis also complements risk assessment activities at Health Canada conducted to inform and support programs and policies designed to mitigate exposure to, and health impacts of, air pollution in Canada. This includes a report evaluating the role of exposure to TRAP in asthma, allergy, and lung function using a weight of evidence approach (Health Canada 2020). Health Canada is also assessing exposure to TRAP in Canada based on a literature review and an analysis of population proximity to roadways. Together, the Health Canada assessments of health risks, population health burden, exposures associated with TRAP in Canada are intended to provide a comprehensive national evaluation.

This report summarizes the methodological approach and the results for each step of the health impact modelling framework, including the air pollutant emissions inventory, the air quality (i.e., ambient air concentrations) modelling simulations, the health impact assessment, and the estimate of socio-economic costs (valuation). Results at the national, provincial and territorial, and census division level are presented and discussed.

2. Methodology

The air pollution and health burden estimates are based on a modelling framework designed for the analysis of source sectors, including on-road vehicles. The modelling framework for this analysis utilizes three main steps and tools that are discussed in sections 2.1 to 2.3:

- Air pollutant emissions inventory;

- Chemical transport modelling of air pollution scenarios; and

- Health impact assessment and valuation.

The general approach was to develop an emissions inventory for the year 2015 (step 1), which included detailed data for traffic and other source sectors of air pollution. In step 2, ambient air pollutant concentrations were estimated using a chemical transport model (CTM). Concentrations attributable to TRAP were determined by comparing the air quality estimates from the CTM for a reference emissions scenario and for a scenario involving complete removal of on-road vehicle emissions. The difference between the two scenarios corresponded to the estimate of the contribution of TRAP to ambient air pollution concentrations. In step 3, TRAP concentrations were input into the Air Quality Benefits Assessment Tool (AQBAT) to estimate the population health burden attributable to TRAP in Canada, including mortality and morbidity outcomes, as well as socio-economic costs. Additional methodological details of the modelling framework are presented in Appendix A.

2.1 Emissions inventory

ECCC developed a detailed emissions inventory for the year 2015, based on the 2017 Air Pollutant Emissions Inventory, to be used as input to the chemical transport model.Footnote 1 It was the most recent and accurate version available when the modelling analysis was initiated. The emissions inventory used for the United States was the 2017 projection emissions inventory based on the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) 2011 National Emissions Inventory (NEI).Footnote 2 The 2008 inventory used for Mexico (Inventario Nacional de Emisiones, INEM)Footnote 3 was also from the US EPA 2011 NEI. The emission estimates were chemically speciated, spatially distributed, and temporally resolved. ECCC used different approaches and data to develop the emissions inventory, including industrial pollutant release data, fuel use data, source-specific activity data and emission factors (ECCC 2015, 2016). Primary emissions were estimated for both anthropogenic and biogenic source categories (except emissions from wildfires). Additional methodological details of emissions modelling are presented in Appendix A.

On-road vehicle emissions were estimated using the Motor Vehicle Emission Simulator (MOVES) version 2014b, developed by the US EPA. The model has been modified to reflect Canadian conditions, such as vehicle population and age distribution, as well as vehicle emission standards. MOVES provides emission rates for a series of pollutants, including CO, ammonia (NH3), nitrogen oxides (NOx), PM, SO2 and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which are then combined with vehicle activity data. Traffic source emissions modelled by MOVES and considered in this analysis included exhaust, evaporative and tire wear and brake lining (TWBL) emissions from gasoline and diesel on-road vehicles, as well as on-road vehicles powered by other fuels (e.g., compressed natural gas). Evaporative emissions from stationary sites, such as those from refuelling stations or fuel storage facilities, were not included as a component of TRAP; they are associated with air pollutant emissions from commercial, institutional, or industrial sources. Dust emissions from paved and unpaved roads were also excluded as a component of TRAP; they are associated with open sourcesFootnote 4 in the APEI and are not allocated to specific segments of the vehicle fleet. On-road transportation emissions were compiled as monthly values for different vehicle types and aggregated at the provincial level, except for British Columbia and Ontario. Sub-provincial vehicle information was available for these two provinces (e.g., inspection and maintenance programs), allowing the creation of sub-regions (two for British Columbia and four for Ontario). Five different road classes were also used to improve the spatial allocation of on-road vehicle emissions: rural restricted and unrestricted access, urban restricted and unrestricted access, and off-network. For on-road transportation emissions specifically, Canadian engine emission standards and fuel regulations effective in 2015 were considered.Footnote 5

The 2015 inventory database was further processed by ECCC to generate a dataset that can be used in the Sparse Matrix Operator Kernel Emissions (SMOKE) model (Sassi et al. 2016). Spatial surrogates from SMOKE version 3.7 (in ASCII format), generated from geographic information system (GIS) shapefiles, were used to allocate emissions to a national grid surface. Ancillary and updated shapefiles were also included to distribute emissions across Canada. The spatially allocated emissions became input to the chemical transport model.

2.2 Air quality modelling

2.2.1 Chemical transport model

The chemical transport model used for this assessment was ECCC's Global Environmental Multiscale – Modelling Air Quality and Chemistry (GEM-MACH) model, version 2.3.1. GEM-MACH, a source-oriented Eulerian model, is a prognostic tool that integrates meteorological data and specific algorithms to simulate the diffusion, transport and chemical transformation of gases and particles in the atmosphere (Makar et al. 2018; Moran et al. 2010; Whaley et al. 2018, 2020). GEM-MACH is used by ECCC to simulate hourly concentrations of air pollutants including O3, PM2.5, NO2, and SO2 over a North American domain, for operational air quality forecasting and in support of air quality regulations and management decisions for Canada.

The general air quality modelling approach included simulations conducted over a continental domain with a horizontal grid spacing of 10 km by 10 km, and 80 hybrid vertical levels extending from the surface (1.5 m) to 0.1 hectopascal (approximately 30 km). GEM-MACH simulations were done for a complete year, computing 24 hours of forecast for each day. The model's time step is 300 seconds, such that meteorological and atmospheric conditions are computed every five minutes. Hourly output values (i.e., pollutant concentrations) are simulated. Simulations were conducted using 2017 meteorology that corresponds to forecasts produced operationally on a daily basis by ECCC in 2017. It includes data assimilation of observations.

The GEM-MACH model was executed on ECCC's High Performance Computing (HPC) system. The simulation was divided into four three-month segments, each with a 21-day spin-up period. The segments correspond to January–March, April–June, July–September and October–December. All segments are computed in parallel to decrease the execution time. A task sequencer is used to manage and submit on the HPC the different steps required to perform an uninterrupted simulation.

The post-processing of GEM-MACH results consists of computing different statistics by using an automated suite of tools, such as Kornshell and Tcl scripts, as well as C/C++ and Fortran programs. The statistics include, for example, averages, rolling averages, maximum values and differences between scenarios, for different periods (monthly, annual and seasonal). Statistics are computed for the model grid and can be interpolated on different geographical areas, such as census divisions (CDs) as used in AQBAT. The final products are available in formats such as ASCII, binary, GIS, and graphical format, depending on the research objectives.

From the gridded modelled results, ambient air pollution estimates were generated at the CD level for NO2, O3, PM2.5 and SO2 for linkage with AQBAT. The results represent regional air pollution conditions and do not reflect local effects and microenvironments that are unresolved by the horizontal grid size, such as roadways and street canyons, where air pollution levels may be higher. Appendix A presents additional methodological details of the GEM-MACH model. Methodological considerations are discussed in section 4.3.

2.2.2 Simulation approach

In order to isolate the contribution of TRAP to ambient pollutant concentrations in Canada, a brute force approach was used wherein two air quality scenarios were modelled with GEM-MACH: (1) a reference scenario with the full Canadian 2015 emissions inventory and (2) a TRAP scenario with on-road vehicle emissions removed from the inventory. The TRAP scenario required zeroing-out all Canadian air pollutant emissions in Canada from motorcycles, light-duty vehicles and heavy-duty vehicles for the calendar year 2015. The differences in air quality between the full emissions inventory scenario and the scenario with Canadian on-road vehicle emissions removed are assumed to represent the contribution to ambient pollutant levels from on-road vehicles in Canada. This increment is also used to estimate the population exposure to TRAP.

2.2.3 Model output

Ground-level concentrations were estimated for each model grid cell and Canadian CD for the following pollutants and concentration metrics:

- Annual average based on:

- hourly data for NO2, PM5, and SO2

- daily maximum of hourly data for O3

- Summer (i.e., May–September) average based on daily maximum of hourly data for O3

The units for NO2, O3 and SO2 are in parts per billion by volume (ppbv), while PM2.5 values are in micrograms per cubic metre (µg/m3). For the current analysis, estimates of ground-level concentrations were not available for all air pollutants in the emissions inventory, including CO and PM10.

Concentration estimates are reported for each province and territory as well as for some individual CDs (section 3.2). For the current analysis, the CDs were based on the Standard Geographical Classification 2011, which divides Canada into 293 CDs.Footnote 6 The CD air pollutant concentrations are area-weighted estimates from the original GEM-MACH grid. Area-weighted concentrations for each CD were determined by summing the product of a grid cell concentration and the area of that grid cell occupied by the CD, for all grid cells intersecting with the CD, and then dividing the sum by the area of the CD. For example, if three grid cells intersect with a CD, the following formula would apply to determine its concentration (Cd):

Cd = (Ad1 × Cg1 + Ad2 × Cg2 + Ad3 × Cg3) ÷ Ad

where Adx is the area of overlap between the model grid cells and the CD, Cgx is the concentration of the grid cell gx, and Ad is the area of the CD.

The reported national, provincial and territorial concentrations correspond to population-weighted estimates. The population-weighting method estimates the average exposure concentration for an individual within a geographic unit. When averaged across larger geographic units, CDs with high populations have more influence or weight than CDs with low populations. Compared to an area-weighted measure, population-weighting provides a better representation of the average pollutant concentration to which Canadians are exposed. This is especially important in Canada as populations are generally limited to urban areas in the southern portion of the country, compared with the vast rural and low population northern areas.

Population-weighted concentrations for all provinces and territories were determined by summing the product of a CD concentration and the population of that CD, for all CDs in a province, and then dividing the sum by the provincial population. For example, if a province includes three CDs, the population-weighted concentration (Cpw) is determined by:

Cpw = (CDd1 × CDpop1 + CDd2 × CDpop2 + CDd3 × CDpop3) ÷ PTpop

where CDdx is the concentration of CDx, CDpopx is the population of CDx, and PTpop is the population of the province. The same method was used to estimate the population-weighted national average.

2.3 Health impact assessment

2.3.1 Calculating population health impacts due to air pollution

The health outcomes attributable to air pollution from the on-road sector were estimated using Health Canada's Air Quality Benefits Assessment Tool (AQBAT) (Judek et al. 2019), version 3.0.Footnote 7 AQBAT estimates the number of premature deaths and other adverse health outcomes in Canada associated with a specified change in ambient concentrations of NO2, O3 and PM2.5. In AQBAT, health effect information for the three air pollutants is included in the form of concentration response functions (CRFs), which describe the association between exposure to an air pollutant and a health response. A CRF represents the excess health risk for a given endpoint (e.g., asthma symptoms, chronic bronchitis, and acute exposure mortality) associated with exposure to a unit increase in ambient pollutant concentration. For example, an increase in PM2.5 chronic exposure of 10 µg/m3 leads to a corresponding 10% increase in the risk of premature mortality from non-accidental causes. CRFs in AQBAT are statistically derived estimates from a single study or a meta-analysis of multiple studies.Footnote 8

Health endpoints related to acute or chronic exposure, the associated CRFs, and the applicable population groups (e.g., age-specific groups) are predefined within AQBAT and represent Health Canada-endorsed values drawn from the peer-reviewed health science literature. AQBAT also includes a CRF for mortality associated with short-term exposure to SO2. However, it was not included in the current analysis to reflect the Health Canada risk assessment for SO2, which concluded that data are only suggestive of a causal relationship between short-term SO2 exposure and all-cause and cardiopulmonary mortality at ambient concentrations (Health Canada 2016b). Health Canada only considers causal and likely causal relationships for quantitative analyses. In the context of this analysis, short-term exposure contributes to effects that occur within a few days of an increase in ambient air pollution (acute health effects), while long-term exposure refers to exposures averaged over the years preceding the development of disease or death (chronic health effects). CRFs pertaining to acute exposure were derived from studies examining effects of air pollutants in the days before health outcomes, whereas CRFs pertaining to chronic exposure were derived from studies of air pollutants averaged over the years prior to health outcomes. The pollutants and their associated health effects considered in this analysis are provided in Table A1, Appendix A. Previous studies (Crouse et al. 2012; Judek et al. 2019; Shin et al. 2013; Stieb et al. 2015) contain background information on the CRF estimates used in this analysis (i.e., references to the scientific literature upon which the risk estimates are based) and the analysis undertaken to produce the estimates within AQBAT. Health outcomes were considered to have no threshold for effect (i.e., effects were assumed to occur at all levels of exposure).

CRFs can be input as a distribution function in AQBAT, accounting for inherent uncertainty in the CRF estimates. Monte Carlo simulations employing 10,000 iterations were used to propagate this uncertainty in the CRFs. The model generates a central estimate of the most likely health impacts equal to the median of the output distribution, as well as low- and high-end estimates equal to the 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles of the output distribution (interpreted as the 95% confidence intervals).

Baseline incidence rates in the Canadian population for each health endpoint (e.g., risk of death due to cardiovascular disease) are needed to estimate counts of health outcomes in a target population. General population and age-specific baseline incidence rates for a target population are included in AQBAT. For example, the Restricted Activity Days endpoint is assigned to 100% of all adults (20 years of age and older) and 85.7% of children aged 5 to 19 years (non-asthmatic). For each morbidity and mortality health endpoint in AQBAT, the baseline incidence rates are represented by a data file containing estimated annual events per million specified population, for every geographic area, age group, scenario year and population projection. Baseline incidence rates are estimated by Health Canada from detection, observation and reporting through formal means (e.g., death certificates, hospital admission records), from data provided by Statistics Canada, the Canadian Institute for Health Information, or from epidemiological studies. Incidence rates are generally associated with many factors, such as age, gender, race, education, income, environmental factors and lifestyle habits. Exposure to pollutants typically has a minor influence on the baseline incidence rates. Additional details and references on the process of deriving baseline rates have previously been published (Judek et al. 2019; Stieb et al. 2015).

2.3.2 Calculating the economic value of health outcomes due to air pollution

Estimating the economic value (or valuation) of air pollution-related health impacts monetizes health outcomes, allowing impacts to be expressed in monetary units. In doing so, the potential social, economic and public welfare consequences of a health endpoint are considered, including medical costs, reduced workplace productivity, pain and suffering, and the other effects of increased health risks. Expressing impacts in monetary terms provides a common metric across health endpoints to estimate the overall benefits or damages in order to inform air quality management strategies. The sum provides an indication of the relative benefits or damages to society resulting from reduced or increased risks to health.

In AQBAT, each health endpoint is assigned a monetary value, typically derived from survey, accounting, economic or actuarial data. The endpoint values have inherent uncertainties, which are captured by a distribution of possible values with corresponding parameters (i.e., valuation estimates are entered as a distribution in AQBAT). The valuation estimates used in the model and references to the studies from which they are derived are provided in Table A2 in Appendix A. Endpoint valuations are expressed in Canadian dollars and can be temporally adjusted from the source years of the underlying studies based on the consumer price index, as defined by Statistics Canada (Judek et al. 2019; Statistics Canada, annual). In the current analysis, data are reported in 2015 Canadian dollars (CAD 2015).

The monetary value of mortality is considerably higher than that of any other health endpoint. For the purpose of policy analysis, the recommended central estimate of an avoided premature death is $6.5 million (CAD 2007) based on a review of Canadian studies by Chestnut and De Civita (2009). It relies on analyses indicating that an average Canadian would be willing to pay approximately $65 in order to reduce the risk of premature death by 1 out of 100,000. The aggregate willingness to pay (WTP) of 100,000 Canadians ($65 each) equals the value of the one avoided death. The uncertainty in this estimate is addressed by a recommended low value of $3.5 million and a high value of $9.5 million. These values represent a reasonable range for a primary analysis but should not be considered as lower and upper bounds (Chestnut and De Civita 2009). The above values are not equivalent to the economic worth of an identified person's life, but rather an aggregation of individuals' willingness to pay for small changes in risk.Footnote 9 Following adjustments based on the consumer price index, the value of an avoided premature death in 2015 CAD is $7.4 million.

3. Results

3.1 Emissions associated with on-road transportation

Table 1 presents the Canadian emissions inventory for the year 2015.Footnote 10 The major source categories are included as well as a more detailed listing of transportation classes (i.e., air, marine, off-road, on-road and rail) and sub-classes for on-road transportation (e.g., class 8 heavy-duty vehicles (HDV8), light-duty trucks (LDT), and light-duty vehicles (LDV)) and open sources, which include agricultural and construction activities as well as emissions from paved and unpaved roads. This inventory was used for the reference scenario during the chemical transport model simulations (step 2). The TRAP scenario used the same inventory but excluded on-road transportation emissions.

Overall, the emissions inventory data show that:

- The transportation sector emits large quantities of air pollutants, particularly CO and NOx.

- On-road vehicles are the largest contributors to CO emissions among the transportation classes, followed by off-road vehicles.

- On-road vehicles are the largest contributors to NOx emissions among the transportation classes, followed by marine vessels.

- Open sources are the largest contributors to NH3 and PM emissions.

- Industrial and non-industrial (e.g., electricity generating units) facilities release most of the SO2 emissions, while industrial facilities also notably contribute to VOC emissions.

Within the transportation category, on-road vehicles release more NH3, NOx and PM10 than other classes. The large number of vehicles in operation on Canadian roads explains the higher emissions for some pollutants (e.g., NOx). For example, in 2015, almost 24 million road motor vehicles were registered in Canada, compared with 2.1 million off-road engines and vehicles.Footnote 11 Off-road engines and vehicles are associated with the highest contributions to PM2.5 and VOC emissions. The less stringent off-road engine emission standards and the characteristics of the off-road engine population (e.g., older model year engines, engines without after-treatment devices) are drivers of high PM2.5 and VOC emissions from this class. Marine transportation emits the largest share of SO2 among transportation classes, with the high SO2 marine emissions being linked to the much higher sulphur content of marine diesel fuel. In 2015, the maximum allowable sulphur content of marine diesel fuel was 1,000 ppm, compared to 15 ppm for on-road, off-road and rail transport.Footnote 12

Within the on-road transportation class, light-duty vehicles and trucks are the largest emitters for CO, NH3, SO2 and VOCs (Table 1). This reflects the large number of LDVs and LDTs as well as the dominant use of spark-ignition engines to power light-duty vehicles in Canada. The smaller segment of the HDV fleet (HDV2B-3) and the larger class 8 heavy-duty vehicles (HDV8) dominate NOx, PM2.5 and PM10 emissions. The dominant use of compression-ignition engines in HDVs is partly responsible for the higher NOx and particulate emissions compared to LDVs. Figure 1 shows emissions by pollutant for LDVs and HDVs at the national level. It also demonstrates the difference in magnitude of emissions among pollutants. Table 2 also presents the relative contribution (in percentage) from on-road transport to the 2015 Canadian emissions inventory.

For the light-duty segments specifically, LDT emissions exceed LDV emissions, with the exception of NH3 (Table 1). Canadian vehicle registration data show that vehicles less than 4,500 kg (LDVs and LDTs) make up most of the on-road fleet, with 22 million out of 24 million registrations in 2015.Footnote 13 Canadian vehicle sales data show that more units of LDTs (trucks, light trucks and vans, minivans, sport utility vehicles, etc.) have been sold than LDVs (passenger cars) since at least 2010.Footnote 14 The heavier LDTs generally have higher fuel consumption rates than LDVs, and are prone to release more friction-based particulate matter emissions associated with brake and tire wear (Wahid 2018).

Figure 1 - Text description

This chart (Figure 1) presents on-road HDV and LDV emissions (in tonnes) in Canada, by pollutant, from the 2015 Air Pollutant Emissions Inventory. The source data are displayed in the following table:

| On-road vehicle class | Emissions by pollutant (in tonnes) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOx | VOC | CO | NH3 | PM10 | PM2.5 | SO2 | |

| Heavy-duty | 284,825 | 30,023 | 466,185 | 1,088 | 14,323 | 10,370 | 346 |

| Light-duty | 103,999 | 95,744 | 1,104,452 | 5,394 | 9,644 | 3,107 | 1,114 |

Particulate emissions consist of three components: exhaust, brake and tire emissions. Exhaust emissions refer to combustion-related emissions that are released from the vehicle tailpipe. Brake and tire emissions depend on friction mechanisms, through contact between vehicle parts and the road surface. They are also referred to as tire wear and brake lining (TWBL) emissions. Similarly, VOC emissions consist of exhaust emissions and evaporative emissions. The latter reflect the VOCs in fuel that evaporate through the fuel and engine system during operation of the vehicle or when it is parked or stored. TWBL and evaporative emissions make up non-combustion or non-exhaust emissions. Additional details on non-exhaust particulate and VOC emissions from on-road transportation are provided in Appendix B.

| Source category and class | CO | NH3 | NOx | PM10 | PM2.5 | SO2 | VOC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incineration | 4,001 | 138 | 1,687 | 42 | 31 | 2,321 | 823 | ||

| Industrial | 1,186,309 | 15,077 | 611,071 | 151,068 | 61,743 | 759,833 | 639,746 | ||

| Miscellaneous | 9,737 | 712 | 76 | 18,183 | 16,746 | 88 | 372,284 | ||

| Non-Industrial | 1,261,307 | 2,744 | 231,665 | 175,017 | 171,213 | 257,673 | 232,765 | ||

| Open SourcesFootnote a | Agriculture | 897 | 454,936 | 4,043 | 1,333,937 | 318,299 | 8,964 | 97,717 | |

| Construction operations | 301 | 31 | 1,686 | 2,524,152 | 504,911 | 351 | 20 | ||

| Dust - paved roads | 0 | 0 | 0 | 576,114 | 139,186 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Dust - unpaved roads | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2,445,421 | 359,730 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 147,491 | 459,299 | 11,320 | 6,901,143 | 1,335,783 | 10,709 | 114,510 | ||

| Transportation | Air | 33,560 | 4 | 5,776 | 356 | 277 | 518 | 2,668 | |

| Marine | 22,353 | 296 | 237,480 | 5,005 | 4,604 | 10,233 | 10,007 | ||

| Off-Road | 1,322,972 | 295 | 201,354 | 19,038 | 18,467 | 240 | 163,260 | ||

| On-RoadFootnote b | HDV2B-3 | 343,018 | 512 | 118,786 | 4,116 | 3,303 | 223 | 14,666 | |

| HDV4-5 | 44,255 | 65 | 18,748 | 688 | 525 | 24 | 2,173 | ||

| HDV6-7 | 38,721 | 97 | 22,009 | 1,499 | 1,081 | 19 | 3,861 | ||

| HDV8 | 40,191 | 413 | 125,283 | 8,019 | 5,461 | 80 | 8,543 | ||

| LDT | 618,266 | 2,606 | 60,981 | 5,452 | 1,651 | 617 | 49,269 | ||

| LDV | 474,416 | 2,753 | 42,425 | 4,166 | 1,437 | 493 | 44,470 | ||

| MC | 11,770 | 34 | 594 | 25 | 19 | 4 | 1,735 | ||

| Total | 1,570,637 | 6,482 | 388,824 | 23,966 | 13,447 | 1,460 | 125,767 | ||

| Total | 2,967,720 | 7,133 | 958,868 | 51,376 | 39,747 | 12,903 | 307,956 | ||

| Rail | 18,198 | 53 | 125,434 | 3,012 | 2,921 | 452 | 6,253 | ||

| Total – all sources | 5,576,565 | 485,102 | 1,814,687 | 7,297,369 | 1,625,262 | 1,043,527 | 1,854,305 | ||

| HDV: Heavy-duty vehicle class; LDT: light-duty truck; LDV: light-duty vehicle; MC: motorcycle | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

Left panel: NH3, PM10, PM2.5 and SO2. Right panel: CO, NOx and VOC

Figure 2 - Text description

The charts in Figure 2 present on-road HDV emissions (in tonnes) in Canada from the 2015 inventory. The left panel includes NH3, PM10, PM2.5 and SO2 emissions, while the right panel includes CO, NOx and VOC emissions. The source data are displayed in the following table:

| Province / Territory | Heavy-duty vehicle emissions by pollutant (in tonnes) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO | NOx | VOC | NH3 | PM10 | PM2.5 | SO2 | |

| Alberta | 120,361 | 73,959 | 7,571 | 304 | 4,528 | 2,659 | 72 |

| British Columbia | 95,621 | 42,887 | 5,164 | 147 | 2,721 | 1,580 | 49 |

| Manitoba | 23,444 | 11,602 | 1,419 | 41 | 921 | 498 | 10 |

| New Brunswick | 7,390 | 6,325 | 592 | 23 | 507 | 268 | 8 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 4,240 | 4,197 | 382 | 16 | 323 | 169 | 5 |

| Nova Scotia | 7,548 | 6,232 | 574 | 24 | 505 | 248 | 11 |

| Northwest Territories | 1,056 | 2,195 | 171 | 8 | 94 | 65 | 1 |

| Ontario | 89,054 | 62,784 | 6,332 | 271 | 5,989 | 2,610 | 106 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1,717 | 1,339 | 125 | 3 | 111 | 65 | 1 |

| Quebec | 60,986 | 49,900 | 4,481 | 175 | 4,242 | 2,186 | 57 |

| Saskatchewan | 54,365 | 23,007 | 3,178 | 74 | 1,561 | 953 | 25 |

| Yukon | 404 | 397 | 34 | 1 | 17 | 12 | 0 |

Left panel: NH3, PM10, PM2.5 and SO2. Right panel: CO, NOx and VOC. CO emissions were divided by ten to scale with values for NOx and VOC.

Figure 3 - Text description

The charts in Figure 3 present on-road LDV emissions (in tonnes) in Canada from the 2015 inventory. The left panel includes NH3, PM10, PM2.5 and SO2 emissions, while the right panel includes CO, NOx and VOC emissions. The source data are displayed in the following table:

| Province / Territory | Light-duty vehicle emissions by pollutant (in tonnes) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO | NOx | VOC | NH3 | PM10 | PM2.5 | SO2 | |

| Alberta | 171,640 | 16,075 | 15,667 | 763 | 2,329 | 632 | 115 |

| British Columbia | 158,122 | 16,756 | 16,410 | 669 | 1,498 | 450 | 103 |

| Manitoba | 54,644 | 5,103 | 5,529 | 244 | 578 | 180 | 36 |

| New Brunswick | 25,864 | 2,389 | 1,988 | 118 | 297 | 74 | 29 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 14,016 | 1,153 | 936 | 66 | 187 | 43 | 18 |

| Nova Scotia | 27,276 | 2,386 | 1,925 | 129 | 320 | 76 | 39 |

| Northwest Territories | 672 | 57 | 66 | 2 | 29 | 5 | 0 |

| Ontario | 346,864 | 32,531 | 28,441 | 1,927 | 4,443 | 1,166 | 469 |

| Prince Edward Island | 6,387 | 591 | 495 | 27 | 59 | 17 | 7 |

| Quebec | 211,379 | 18,558 | 16,118 | 1,132 | 2,560 | 629 | 244 |

| Saskatchewan | 87,179 | 8,368 | 8,134 | 315 | 840 | 288 | 55 |

| Yukon | 408 | 32 | 34 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 0 |

Figures 2 to 4 present on-road vehicle emissions by province and territory for the heavy-duty and light-duty segments of the fleet, while national estimates are shown in Figure B1 (Appendix B). The data are also presented in Table B2 in Appendix B. Although there are slight variations among regions, the inventory shows that heavy-duty vehicles emit more NOx and PM, whereas light-duty vehicles emit larger quantities of NH3, SO2 and VOCs. In terms of regional results, emissions are higher in Ontario and Alberta, followed by Quebec and British Columbia. The magnitude of emissions is generally consistent with population size, except for Alberta. HDV emissions in Alberta are comparable to those in Ontario, although the population of Ontario is approximately three times that of Alberta. Vehicle registration data for 2015 indicate a higher number of HDVs registered in Alberta (112,109) than in other provinces, except Ontario (122,462).Footnote 16

Table 2 presents the relative contribution (in percentage) from on-road transport to the 2015 Canadian emissions inventory. Overall, 28% of CO emissions and 21% of NOx emissions in Canada are from on-road transport. A modest contribution of 7% to VOC is also estimated, while less than 2% of emissions for PM10, PM2.5, NH3 and SO2 are from on-road transport. Variations across provinces and territories are influenced by dominant (or absent) economic sectors in each region. For example, the upstream petroleum industry releases a greater proportion of NOx emissions in Alberta, lowering contributions from TRAP to 13%. The marine, off-road transportation, ores and mineral industry and upstream petroleum industry sectors also contribute more to NOx emission than on-road transport in Newfoundland, where the transport sector contributes only 8% of the NOx emissions. In Nova Scotia, the lower relative contribution to NOx emissions from on-road transport is due to higher emissions from the coal-fired electric power generation sector. The relatively higher contributions to NH3 emissions from on-road transport observed in the Northwest Territories and Yukon mainly reflect the absence of intensive agricultural activities in those regions, which are responsible for most of the NH3 emissions elsewhere in Canada. Consequently, the interpretation of relative contributions to regional air pollutant emissions is context-specific and requires knowledge of key activity sectors in each province or territory.

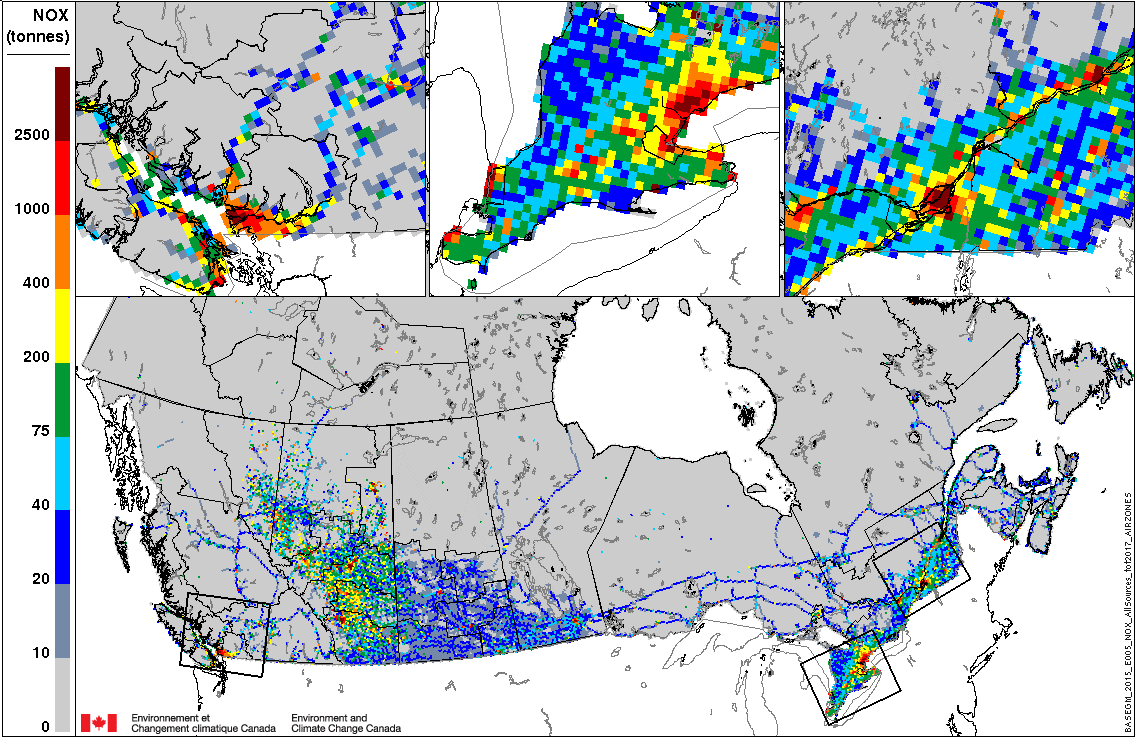

Maps were generated to visualize the distribution of air pollutant emissions across Canada (Figures B2–B7, Appendix B). In general, air pollutant emission levels generally coincide with the population distribution in Canada, with higher values in urban centres and surrounding areas. In addition, regions with extensive industrial activity, including oil and gas production and mining activities as well as agricultural activities, are associated with higher air pollutant emissions. The maps for PM2.5, NOx and VOC emissions from all source sectors and from on-road transportation explicitly are shown and discussed in more detail in Appendix B.

| Province and territory | CO | NH3 | NOx | PM10 | PM2.5 | SO2 | VOC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland & Labrador | 9.7 | 10 | 8.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 2.8 |

| Nova Scotia | 25 | 4.4 | 12 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 6.6 |

| Prince Edward Island | 26 | 1.3 | 40 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 8.2 |

| New Brunswick | 27 | 4.2 | 27 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 8.3 |

| Quebec | 18 | 1.9 | 32 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 7.2 |

| Ontario | 31 | 2.6 | 34 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 9.6 |

| Manitoba | 40 | 0.5 | 36 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0 | 10 |

| Saskatchewan | 46 | 0.4 | 22 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 4.9 |

| Alberta | 28 | 0.8 | 13 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 3.8 |

| British Columbia | 40 | 4.5 | 23 | 1.0 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 13 |

| NunavutFootnote a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Northwest Territories | 23 | 47 | 14 | 0.9 | 2.9 | 0.2 | 8.7 |

| Yukon | 37 | 52 | 47 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 7.9 |

| Canada | 28 | 1.3 | 21 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 6.8 |

| Estimates are rounded, limited to one decimal, and given to a maximum of two significant figures. | |||||||

|

|||||||

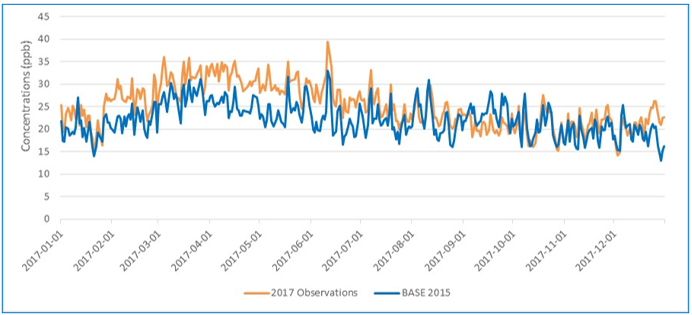

3.2 Modelled contributions from TRAP to ambient air pollution

Average ambient concentrations estimated using the GEM-MACH air quality model are presented in this section for each pollutant, by province and territory. Results for individual CDs are also listed. The terms reference, net and relative concentrations are used for interpreting the results. Reference concentrations are the modelled results obtained from the reference simulation that included the entire emissions inventory. It is important to note that these reference concentrations are direct output from the GEM-MACH model simulations. They have not been adjusted to ambient air monitoring data. The reference concentrations should be interpreted within the context of this analysis. A performance analysis was performed for the specific combinations of the APEI, spatial surrogates and the GEM-MACH version used in the current analysis, and is presented in section 4.3.2.5 and in Appendix D. Performance of the GEM-MACH model was also reported previously in the peer-reviewed literature (Makar et al. 2014a, 2014b; Whaley et al. 2018). Air pollution maps for the reference scenario are shown in Appendix C and are the estimated ambient concentrations for 2015. The net and relative contributions are the modelled ambient air pollution concentration increments associated with Canadian on-road vehicle emissions, in absolute mass (µg/m3 or ppbv) and relative terms (%), respectively.

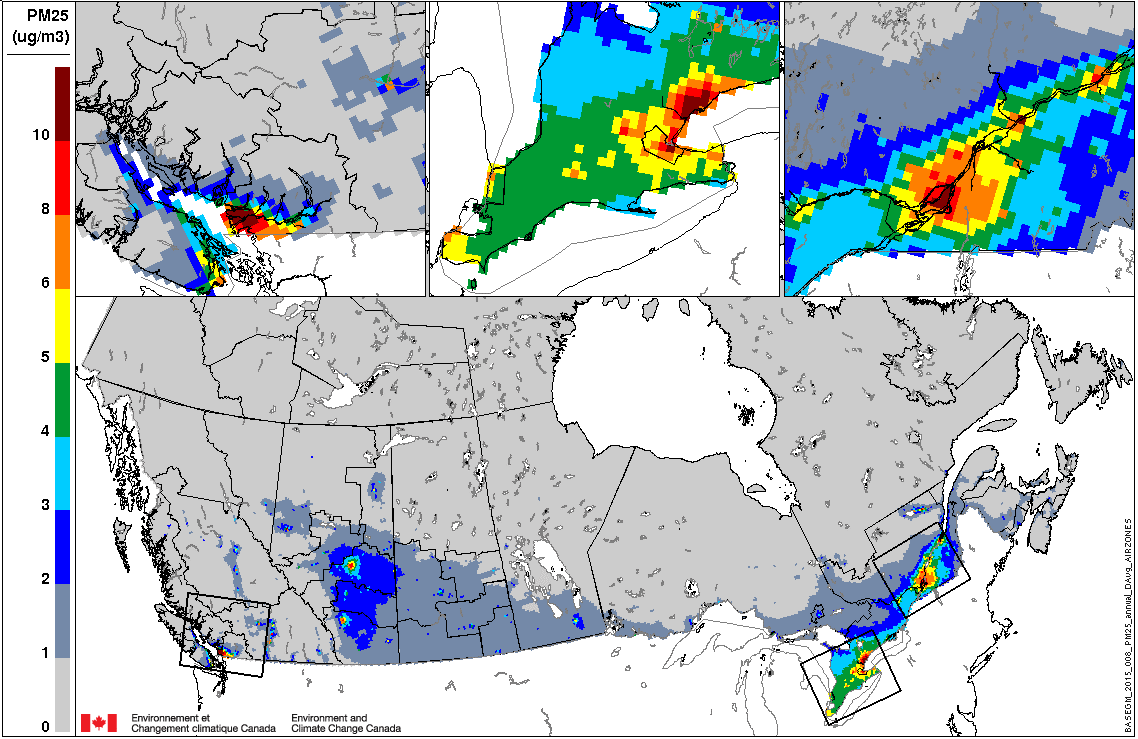

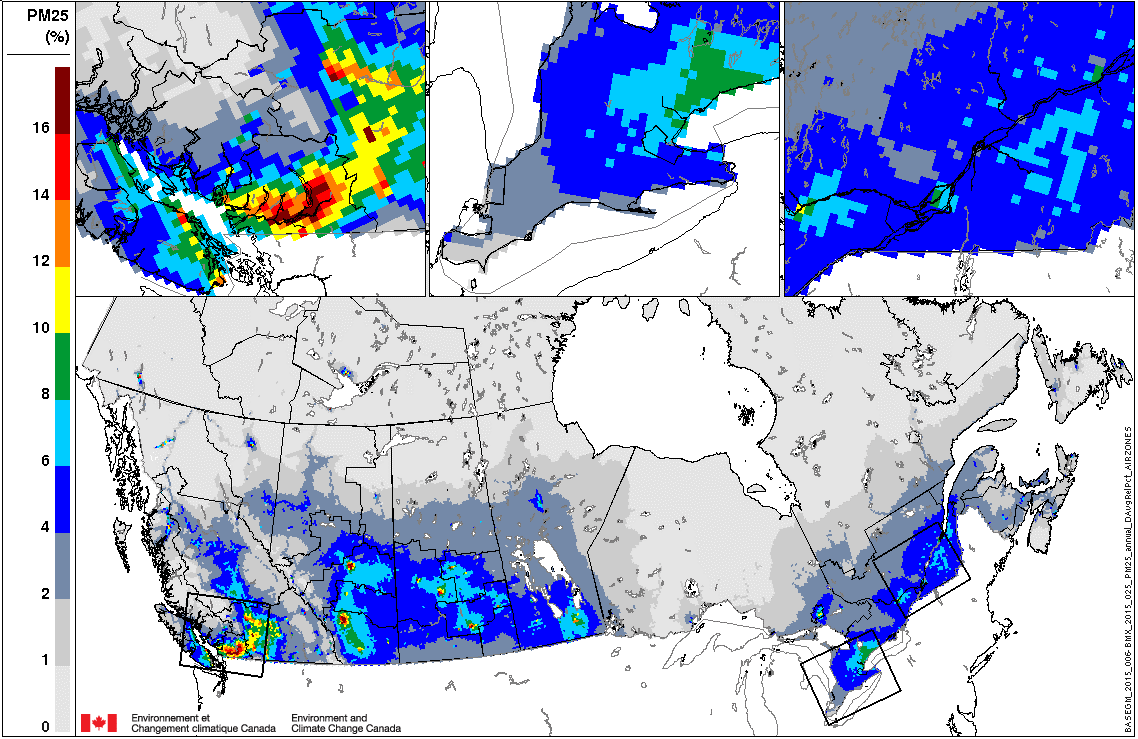

3.2.1 Fine particulate matter

Table 3 shows the national and provincial PM2.5 reference concentrations (modelled) as well as contributions from TRAP alone (in descending order of absolute net contribution). The Canadian average population-weighted reference PM2.5 concentration is estimated to be 5.3 µg/m3. Provincially, higher reference levels are estimated in Quebec (7.8 µg/m3), Ontario (6.4 µg/m3) and British Columbia (4.2 µg/m3). Figure C1 in Appendix C shows that grid cells associated with higher area-weighted PM2.5 concentrations (i.e., 8 µg/m3 or more) correspond with urban centres including Vancouver, Edmonton, Toronto and Montreal. As noted previously for the geographical distribution of emissions, higher concentrations are modelled in densely populated areas and those with intensive industrial activity. Concentrations of 2 µg/m3 or less are projected in remote and rural areas of Canada.

Population-weighted annual average estimates indicate that nationally, 0.4 µg/m3 or 7.0% of ambient PM2.5 concentration is attributable to Canadian on-road vehicle emissions. The relative contribution from TRAP to ambient PM2.5 levels is highest in Manitoba (10%), followed by British Columbia (9.6%), Alberta (8.0%) and Ontario (7.1%).

| Region | Populationa | Reference concentration – µg/mFootnote a | Contribution from on-road | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net – µg/m3 | Relative – % | |||

| Ontario | 13,792,052 | 6.4 | 0.5 | 7.1 |

| Quebec | 8,263,600 | 7.8 | 0.5 | 5.9 |

| British Columbia | 4,683,139 | 4.2 | 0.4 | 9.6 |

| Manitoba | 1,293,378 | 2.6 | 0.3 | 10 |

| Alberta | 4,196,457 | 2.7 | 0.2 | 8.0 |

| Saskatchewan | 1,133,637 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 6.2 |

| Prince Edward Island | 146,447 | 1.3 | < 0.1 | 3.6 |

| New Brunswick | 753,871 | 1.2 | < 0.1 | 2.7 |

| Nova Scotia | 943,002 | 1.1 | < 0.1 | 2.3 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 527,756 | 0.5 | < 0.1 | 1.2 |

| Northwest Territories | 44,088 | 0.2 | < 0.1 | 2.0 |

| Nunavut | 36,919 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Yukon | 37,428 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada | 35,851,774 | 5.3 | 0.4 | 7.0 |

| Net values rounded to one decimal. Relative values limited to two significant figures. Values may not correspond due to rounding. For example, the reference concentration for Ontario is 6.38 µg/m3 and the net contribution from on-road is 0.45 µg/m3 when using two decimals, giving a relative contribution of 7.1%. By contrast, values rounded to one decimal, as shown in the table, equate to 7.8%. | ||||

|

||||

Area-weighted concentrations at the individual CD level (Table 4) show that the highest net contributions to PM2.5 from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions (0.9 µg/m3) are modelled in Toronto and Laval, followed by Montreal (0.8 µg/m3), while the highest relative contributions are modelled in Greater Vancouver (9.9%), Toronto (8.4%) and York (8.4%). A combination of primary PM2.5 emissions and secondary aerosol formation likely contribute to higher contributions in these CDs. The higher relative value in Vancouver reflects the high population density in the Vancouver area, where 50% of the British Columbia population resides, which involves a high level of personal and commercial traffic. It is also dependent on the low reference concentrations estimated for the Greater Vancouver CD. Additional factors that can influence the contribution from TRAP to ambient levels in all CDs include geographical features (e.g., valleys, mountain ranges, open land) and meteorological conditions (e.g., thermal inversions) that may favour elevated air pollution in a region. Except for the Les Moulins CD in Quebec, most CDs listed in Table 4 correspond to relatively dense urban areas that include high-volume roadways. The Les Moulins CD is located north-northeast and generally downwind of Greater Montreal, and is crossed by two primary highways and several high-volume roadways; this may partly explain the higher estimated contributions in this CD. The results from this analysis are available for all CDs and can be obtained upon request from Health Canada by sending an email to air@hc-sc.gc.ca.

| Region | PopulationFootnote a | Reference concentration – µg/m3 | Contribution from on-road | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net – µg/m3 | Relative – % | |||

| ON- Toronto (CD3520) | 2,826,498 | 10.7 | 0.9 | 8.4 |

| QC- Laval (CD2465) | 425,225 | 11.9 | 0.9 | 7.2 |

| QC- Montréal (CD2466) | 1,999,795 | 11.9 | 0.8 | 6.5 |

| BC- Greater Vancouver (CD5915) | 2,504,363 | 6.5 | 0.6 | 9.9 |

| QC- Longueuil (CD2458) | 421,342 | 10.8 | 0.6 | 5.8 |

| ON- Peel (CD3521) | 1,438,770 | 7.2 | 0.6 | 7.8 |

| QC- Les Moulins (CD2464) | 159,098 | 11.0 | 0.5 | 4.9 |

| QC- Québec (CD2423) | 580,639 | 7.9 | 0.5 | 6.7 |

| ON- York (CD3519) | 1,140,024 | 6.3 | 0.5 | 8.4 |

| ON- Halton (CD3524) | 559,213 | 7.2 | 0.5 | 7.3 |

| Canada | 35,851,774 | 5.3 | 0.4 | 7.0 |

BC: British Columbia; ON: Ontario; QC: Quebec Net values rounded to one decimal. Relative values limited to two significant figures. Values may not correspond due to rounding. |

||||

|

||||

Figure 4 shows the net contributions from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to ambient PM2.5 concentrations across Canada in 2015. Relative contributions are shown in Figure C2, Appendix C. The maps use the gridded results from the GEM-MACH model and have a resolution of 10 km by 10 km. They do not include any population or area weighting and consequently may differ slightly from the CD-based results presented above. The scale in Figure 4 varies from 0 to approximately 2 µg/m3. Higher contributions are observed in the southwestern part of British Columbia, around Edmonton and Calgary, and along the Windsor–Québec Corridor, which correspond to areas of higher population. In and around the most populated urban centres (Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Regina, Winnipeg, Toronto, and Montreal), contributions from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions are between 0.4 and 1.4 µg/m3. Higher values are estimated in Calgary and Edmonton. The individual maps for LDVs and HDVs (not shown) suggest that within urban centres, both vehicle classes contribute fairly equally to ambient PM2.5 concentrations, combining for greater impacts in these grid cells. However, the contribution from HDVs is visible beyond the urban core, covering metropolitan and adjoining areas more broadly than contributions from LDVs.

Notes: Insets for southern British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec

Figure 4 - Text description

Map of Canada showing the net contribution (µg/m3) from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to annual average PM2.5 concentrations in 2015. The map is based on a model simulation with a 10-km grid resolution. Insets showing enlarged regions for southern British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec are included. Net contributions vary from 0 to 1.6 µg/m3. Contributions less than 0.2 µg/m3 are generally modelled outside the larger urban and suburban areas. Areas along the Windsor-Quebec City corridor are associated with contributions of 0.2 to 0.8 µg/m3, reaching 0.8–1.2 µg/m3 in the Toronto, Montreal and Quebec City urban centres. Regions in southwestern British Columbia including the Lower Fraser Valley show contributions of 0.2 to 1.4 µg/m3, with contributions highest in Vancouver. The highest modelled contributions overall, 1.4–1.6 µg/m3, are in Edmonton and Calgary, Alberta.

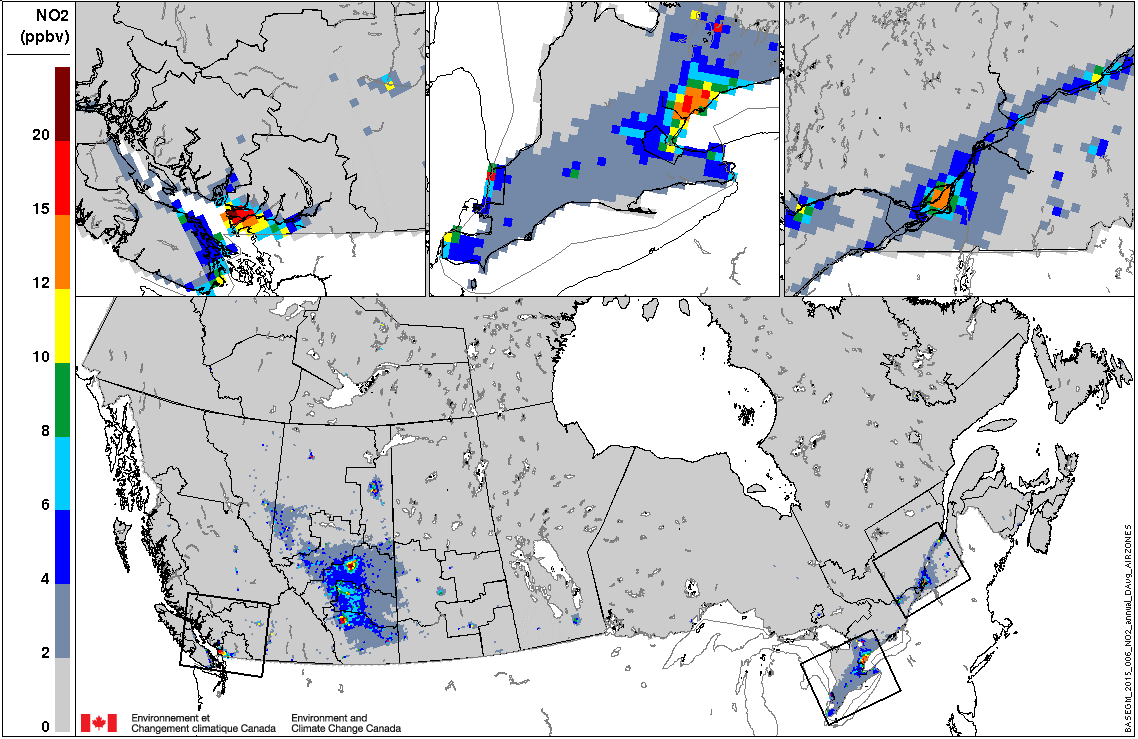

3.2.2 Nitrogen dioxide

Table 5 shows the national and provincial NO2 reference concentrations (modelled) as well as contributions from TRAP alone (in descending order of absolute net contribution). The modelled Canadian average reference population-weighted NO2 concentration is 5.1 ppbv.Footnote 17 Higher reference levels than the national average are estimated in Ontario (6.2 ppbv), Quebec (5.6 ppbv), and Alberta (5.1 ppbv). Figure C3 in Appendix C shows that grid cells with the highest NO2 concentrations (i.e., 10 to 20 ppbv) include the major urban centres of Vancouver, Edmonton, Calgary, Toronto and Montreal. Higher concentrations (approximately 2 to 10 ppbv) are generally associated with populated areas and those with intensive oil and gas industrial activity. Concentrations of 2 ppbv or less are estimated for remote and rural areas of Canada.

Table 5 also indicates that, across Canada, 2.0 ppbv or 38% of the annual population-weighted NO2 concentration is attributable to Canadian on-road vehicle emissions. The highest net contribution is reported in Quebec (2.5 ppbv), followed by British Columbia (2.2 ppbv) and Ontario (2.2 ppbv). The relative contribution from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to ambient NO2 exceeds the national relative contribution of 38% in three provinces: Manitoba (51%), British Columbia (47%) and Quebec (45%). This demonstrates the preponderance of on-road vehicle emissions as a source of NO2 in those regions. Lower relative contributions can reflect the presence of important NOx sources other than on-road vehicles in a province, including upstream petroleum industry activities, electric power generation and off-road vehicles (e.g., mining and oil sands in the case of Alberta). Further, relative contributions are dependent on provincial reference concentrations.

| Region | PopulationFootnote a | Reference concentration – ppbv | Contribution from on-road | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net – ppbv | Relative – % | |||

| Quebec | 8,263,600 | 5.6 | 2.5 | 45 |

| British Columbia | 4,683,139 | 4.8 | 2.2 | 47 |

| Ontario | 13,792,052 | 6.2 | 2.2 | 35 |

| Manitoba | 1,293,378 | 3.7 | 1.9 | 51 |

| Alberta | 4,196,457 | 5.1 | 1.3 | 25 |

| Saskatchewan | 1,133,637 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 24 |

| Prince Edward Island | 146,447 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 36 |

| Nova Scotia | 943,002 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 30 |

| New Brunswick | 753,871 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 27 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 527,756 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 23 |

| Northwest Territories | 44,088 | 0.1 | < 0.1 | 7.3 |

| Yukon | 37,428 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | 25 |

| Nunavut | 36,919 | < 0.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada | 35,851,774 | 5.1 | 2.0 | 38 |

| Net values rounded to one decimal. Relative values limited to two significant figures. Values may not correspond due to rounding. | ||||

|

||||

| Region | PopulationFootnote a | Reference concentration – ppbv | Contribution from on-road | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net – ppbv | Relative (%) | |||

| QC- Laval (CD2465) | 425,225 | 10.5 | 5.6 | 53 |

| ON- Toronto (CD3520) | 2,826,498 | 14.0 | 4.9 | 35 |

| QC- Montréal (CD2466) | 1,999,795 | 11.1 | 4.7 | 42 |

| QC- Longueuil (CD2458) | 421,342 | 7.6 | 3.9 | 51 |

| BC- Greater Vancouver (CD5915) | 2,504,363 | 7.8 | 3.7 | 47 |

| QC- Québec (CD2423) | 580,639 | 6.9 | 3.4 | 50 |

| MB- Division No. 11 (CD4611) | 721,819 | 5.9 | 3.2 | 55 |

| QC- Les Moulins (CD2464) | 159,098 | 6.1 | 3.0 | 50 |

| ON- Peel (CD3521) | 1,438,770 | 7.5 | 2.9 | 39 |

| ON- Halton (CD3524) | 559,213 | 6.7 | 2.9 | 43 |

| Canada | 35,851,774 | 5.1 | 2.0 | 38 |

BC: British Columbia; MB: Manitoba; ON: Ontario; QC: Quebec Net values rounded to one decimal. Relative values limited to two significant figures. Values may not correspond due to rounding. |

||||

|

||||

The CD results (Table 6) indicate that the highest net contribution to ambient NO2 from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions is observed in Laval (5.6 ppbv) and the highest relative contribution is observed in Division No. 11,Footnote 18 Manitoba (55%). High relative values are associated with urban areas as well as with suburban regions, indicating an influence of local emissions and regional sources through dispersion of traffic NOx emissions released in larger urban centres, such as Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver.

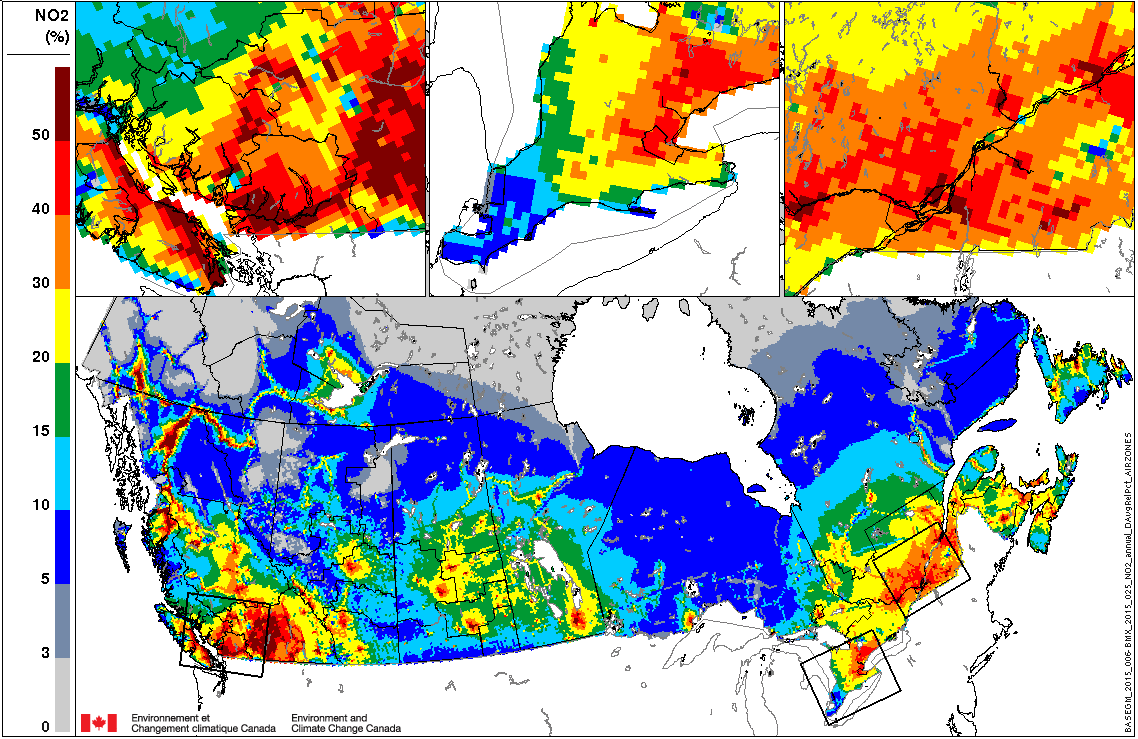

Figure 5 shows the contribution from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to ambient NO2 concentrations at the grid cell level. The scale in Figure 5 goes up to 10 ppbv. In addition to the grid cells corresponding to CDs listed in Table 6, relatively high contributions to NO2 concentrations are modelled in Edmonton and Calgary. The general distribution of TRAP contributions to ambient NO2 concentrations is comparable to that of PM2.5. Relative contributions to ambient NO2 concentrations are shown in Figure C4 (Appendix C). Relative contributions modelled in remote regions (up to 15%), where local NOx on-road vehicle emissions are minimal, can be associated with very low ambient concentrations (Figure C3), the absence of significant local sources, and atmospheric transport. The modelled absolute contribution from on-road vehicles is generally less than 0.25 ppbv in those regions.

Notes: Insets for southern British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec

Figure 5 - Text description

Map of Canada showing the net contribution (ppbv) from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to annual average NO2 concentrations in 2015. The map is based on a model simulation with a 10-km grid resolution. Insets showing enlarged regions for southern British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec are included. Net contributions vary from 0 to more than 10 ppbv. Contributions less than 0.25 ppbv are generally modelled outside the larger urban and suburban areas, as well as outside the more important transportation corridors. Areas along the Windsor-Quebec City corridor are associated with contributions of 0.25 to 3 ppbv, increasing to 3–10 ppbv nearer to and within the larger urban centres of Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal and Quebec City. Regions in southwestern British Columbia including Victoria and the Lower Fraser Valley show contributions of 0.25 to 3 ppbv, with higher contributions of 3–10 ppbv in Victoria and the Metro Vancouver areas. Areas along the Calgary-Edmonton corridor are also associated with contributions of 0.25 to 3 ppbv, increasing and surpassing 10 ppbv in Edmonton and Calgary. Contributions up to 10 ppbv are also noted near other large urban centres in Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

3.2.3 Ozone – summer

O3 concentrations were estimated for the summer period (May 1 to September 30), when O3 production is generally higher owing to warmer temperatures, increased biogenic VOC emissions and longer daylight hours. Table 7 shows the national and provincial summer O3 reference concentrations (modelled) as well as contributions from TRAP alone (in descending order of absolute net contribution). The modelled Canadian average reference summer O3 concentration was 40.0 ppbv. This represents the average daily maximum of hourly data for O3 for the summer period. Higher reference levels were modelled in Ontario (43.8 ppbv), Alberta (41.4 ppbv) and British Columbia (39.5 ppbv). Figure C5 in Appendix C generally shows higher summer O3 concentrations (37 ppbv or more) in the more densely populated and developed regions of Canada, compared to concentrations of 30 ppbv or less in remote and rural areas. Particularly high summer O3 concentrations (greater than 40 ppbv) were estimated between Sarnia and Hamilton and along the northern shore of Lake Erie, as well as in areas directly downwind of major urban centres, including Vancouver, Calgary and Montreal. Areas with sources of elevated NOx emissions, such as high-traffic roadways and urban centres, often have lower O3 levels compared to areas further downwind (e.g., suburban areas) owing to the scavenging (titration) effect of NO. This is linked to the photochemical reactions involving NOx, O3 and VOCs in ambient air that can increase or decrease O3 concentrations. Environmental (e.g., large water bodies, valleys) and meteorological conditions can also influence ambient O3 levels.

Modelled contributions from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to ambient summer O3 concentrations at the national and provincial levels were limited to less than 4%. On average across Canada, on-road vehicle emissions were responsible for 0.9 ppbv or 2.3% of ambient summer O3. The highest net and relative provincial contributions from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to ambient summer O3 were reported in Alberta (1.6 ppbv, 3.7%), Quebec (1.4 ppbv, 3.8%) and Saskatchewan (1.0 ppbv, 2.8%).

| Region | PopulationFootnote a | Reference concentration – ppbv | Contribution from on-road | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net – ppbv | Relative – % | |||

| Alberta | 4,196,457 | 41.4 | 1.6 | 3.7 |

| Quebec | 8,263,600 | 36.5 | 1.4 | 3.8 |

| Saskatchewan | 1,133,637 | 36.2 | 1.0 | 2.8 |

| Prince Edward Island | 146,447 | 34.2 | 0.8 | 2.4 |

| New Brunswick | 753,871 | 33.5 | 0.8 | 2.3 |

| Manitoba | 1,293,378 | 32.7 | 0.8 | 2.3 |

| Ontario | 13,792,052 | 43.8 | 0.7 | 1.5 |

| Nova Scotia | 943,002 | 36.2 | 0.7 | 1.8 |

| British Columbia | 4,683,139 | 39.5 | 0.6 | 1.5 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 527,756 | 34.8 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| Northwest Territories | 44,088 | 29.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Yukon | 37,428 | 28.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Nunavut | 36,919 | 30.5 | < 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Canada | 35,851,774 | 40.0 | 0.9 | 2.3 |

| Net and relative values rounded to one decimal. Values may not correspond due to rounding. | ||||

|

||||

As shown in Table 8, the highest net and relative contributions from on-road vehicle emissions to summer O3 were estimated in Central Okanagan (5.2 ppbv; 14%) and Fraser Valley (3.3 ppbv; 8.7%), British Columbia, followed mostly by suburban CDs downwind of Montreal, Quebec. These CDs do not correspond to urban core areas, or those linked to the highest NO2 contributions (see Table 6), but they still correspond to areas of higher NO2 levels (see Figure 5). This likely relates to the influence of NOx emissions transported from urban centres towards areas with relatively high VOC concentrations and limited local sources of NOx emissions (i.e., NOx-limited conditions).

The contribution from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to summer O3 concentrations was negative in the CDs of Toronto (-1.3 ppbv or -2.8%) and Greater Vancouver (-0.6 ppbv or -1.3%). On-road vehicles do not emit O3 directly; they emit pollutants that react to increase or decrease ambient O3 concentrations. Shifting the balance among O3 precursors, especially NOx, can lead to changes in ambient O3 in both directions. Under some conditions, elevated local traffic-related NOx emissions may titrate O3 molecules and cause a decrease in ambient O3 levels in urban areas (i.e., VOC-limited/NOx-inhibited conditions). The apparent air quality benefit in Toronto and Greater Vancouver is associated with removing on-road emissions (a large source of NOx emissions) in those urban areas. Higher contributions to summer O3 from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions were modelled in areas adjacent to these CDs and that may be impacted by urban emissions, such as Fraser Valley, Central Okanagan, and Cowichan Valley near Greater Vancouver (Table 8). Decreases in ambient O3 concentrations in urban areas associated with elevated NOx emissions, and increases in suburban or rural areas downwind from urban areas, have been widely observed and discussed in previous analyses (Environment Canada and Health Canada 2011; Jhun et al. 2015).

| Region | PopulationFootnote a | Reference concentration – ppbv | Contribution from on-road | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net – ppbv | Relative – % | |||

| BC- Central Okanagan (CD5935) | 197,287 | 37.6 | 5.2 | 14 |

| BC- Fraser Valley (CD5909) | 301,097 | 38.1 | 3.3 | 8.7 |

| QC- Nicolet-Yamaska (CD2450) | 22,889 | 38.8 | 3.1 | 7.9 |

| QC- Francheville (CD2437) | 153,691 | 37.5 | 2.9 | 7.6 |

| QC- Pierre-de-Saurel (CD2453) | 51,088 | 40.2 | 2.8 | 7.1 |

| QC- Drummond (CD2449) | 102,797 | 38.4 | 2.8 | 7.4 |

| QC- Les Maskoutains (CD2454) | 86,201 | 39.6 | 2.8 | 7.1 |

| QC- Bécancour (CD2438) | 20,346 | 37.0 | 2.8 | 7.5 |

| BC- Cowichan Valley (CD5919) | 82,605 | 35.8 | 2.6 | 7.1 |

| QC- Acton (CD2448) | 15,443 | 37.6 | 2.6 | 6.8 |

| Canada | 35,851,774 | 40.1 | 0.9 | 2.3 |

BC: British Columbia; QC: Quebec Net values rounded to one decimal. Relative values limited to two significant figures. Total may not correspond due to rounding. |

||||

|

||||

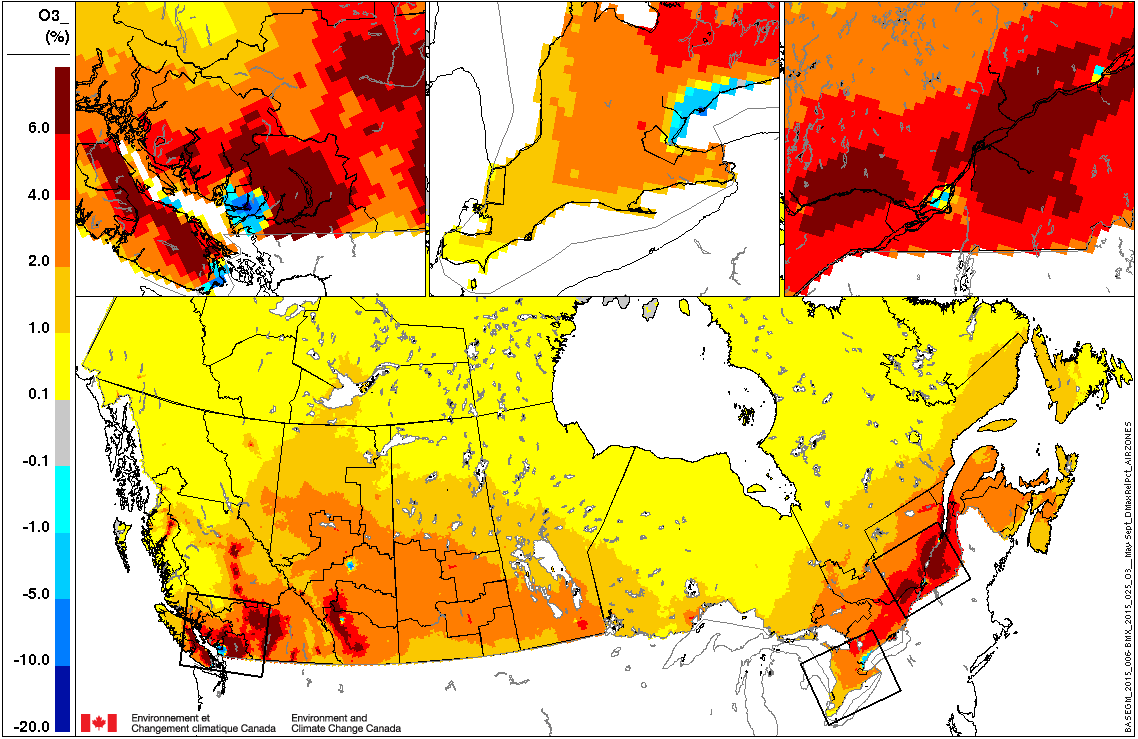

Figure 6 shows the contribution from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to ambient summer O3 concentrations (average daily 1-hour maximum concentrations). Contributions between 2 and 3 ppbv are modelled in western provinces and along the southern parts of Ontario and Quebec. The insets show decreases in summer O3 levels in grid cells corresponding to densely populated areas, including Metro Vancouver, the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA) and downtown Montreal. The relative contribution map (Figure C6, Appendix C) provides comparable information about the impacts of TRAP on summer O3 levels. Relative contributions across individual grid cells vary between decreases of 10% to 20% and increases of 6%.

Notes: Insets for southern British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec

Figure 6 - Text description

Map of Canada showing the net contribution (ppbv) from Canadian on-road vehicle emissions to summer average daily maximum O3 concentrations in 2015. The map is based on a model simulation with a 10-km grid resolution. Insets showing enlarged regions for southern British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec are included. Net contributions vary from -5 ppbv to more than 3 ppbv. Negative contributions are modelled in some of the larger urban centres, reaching -1 to -5 ppbv in Victoria, Vancouver, Edmonton and Toronto, and -0.5 to -1 ppbv in Montreal. Beyond urban cores, contributions to summer average daily maximum O3 concentrations are positive. Contributions of 0.5 to 1.5 ppbv are modelled over the southern part of Western Canada as well as the southern parts of Ontario and Quebec, and regions south of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Areas in southwestern British Columbia and the corridor between Prince George and the Okanagan Valley, the corridor between Calgary and Lethbridge in Alberta, and the Windsor-Quebec City corridor are associated with contributions of 1.5 to 3 ppbv. Locations downwind of large urban centres, notably in British Columbia, Alberta and Quebec, are associated with contributions greater than 3 ppbv.

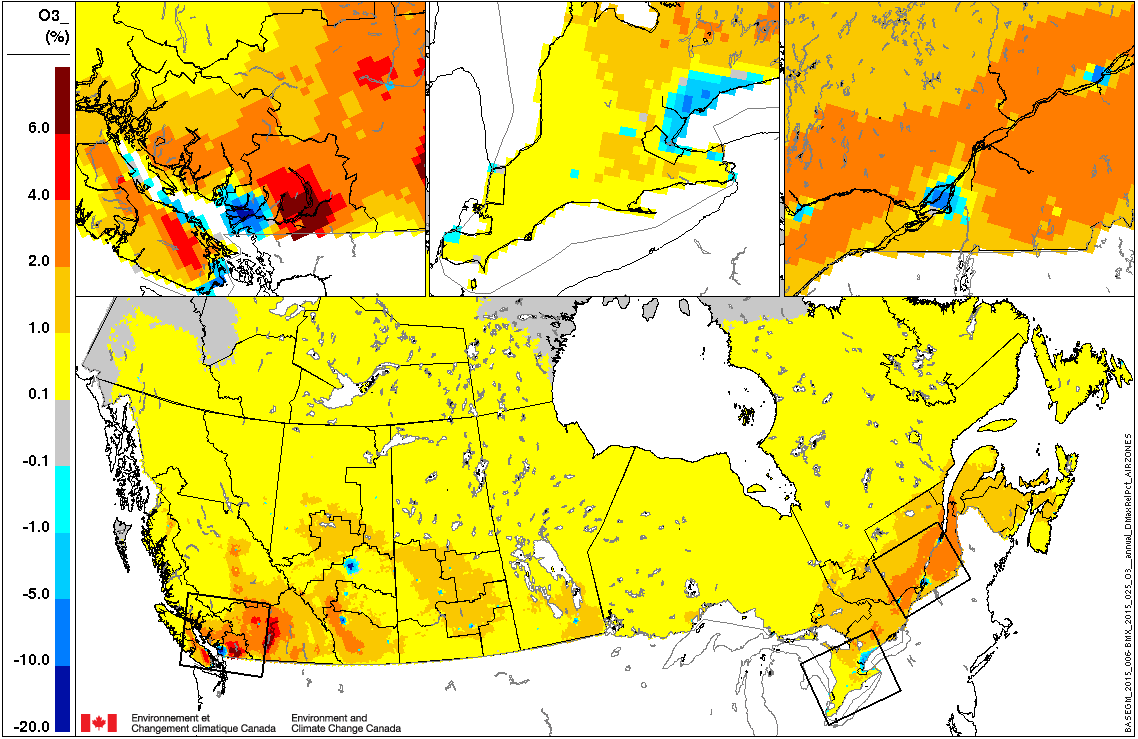

3.2.4 Ozone – annual

Table 9 shows the national and provincial annual O3 reference concentrations (modelled) as well as contributions from TRAP alone (in descending order of absolute net contribution). The modelled Canadian average annual O3 reference concentrationFootnote 19 was 36.4 ppbv. This represents the average daily maximum of hourly data for O3 for the entire year. Provincial reference concentrations were higher in Ontario (38.6 ppbv), Alberta (37.3 ppbv), Nova Scotia (36.5 ppbv) and Newfoundland and Labrador (36.4 ppbv). Figure C7 in Appendix C indicates that the highest annual O3 concentrations (40 ppbv or more) at the grid cell level were modelled in areas around urban centres and along the region between Sarnia and Hamilton, as well as on the northern shore of Lake Erie. In remote and rural areas of Canada, annual O3 concentrations were 30 ppbv or less. In general, the geographic distributions of annual and summer O3 concentrations are comparable (see figures C5 and C7). However, annual O3 concentrations are generally lower than summer O3, such that high annual O3 concentration grid cells are fewer and less geographically dispersed.

National population-weighted annual average estimates indicate that Canadian on-road vehicle emissions decrease annual O3 concentrations by 0.1 ppbv or 0.3%. As noted previously, sources of elevated NOx emissions such as on-road vehicle traffic can lower O3 levels owing to the scavenging effect of NO. The decrease O3 concentrations reflects complex photochemical reactions involving NOx, O3 and VOCs in ambient air and the influence of meteorological conditions. The modelled small decrease in annual O3 concentrations does not indicate that on-road vehicle emissions are beneficial to air quality. Traffic emissions were also modelled to decrease annual O3 concentrations by 0.3 ppbv in British Columbia, 0.2 ppbv in Ontario, 0.2 ppbv in Manitoba and 0.1 ppbv in Quebec (less than 1% of the reference concentration in each province). By contrast, the highest net and relative contributions from on-road vehicle emissions to annual O3 are modelled in New Brunswick (0.4 ppbv, 1.1%), Prince Edward Island (0.4 ppbv, 1.1%) and Saskatchewan (0.4 ppbv, 1.1%).

| Region | PopulationFootnote a | Reference concentration – ppbv | Contribution from on-road | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net – ppbv | Relative – % | |||

| Prince Edward Island | 146,447 | 35.4 | 0.4 | 1.1 |

| Saskatchewan | 1,133,637 | 34.5 | 0.4 | 1.1 |

| New Brunswick | 753,871 | 34.4 | 0.4 | 1.1 |

| Nova Scotia | 943,002 | 36.5 | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| Alberta | 4,196,457 | 37.3 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 527,756 | 36.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 |