Justifications and policy rationales for radon action

Table of contents

- Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Radon is a unique issue

- 3. Avoiding personal risks

- 4. Consumer protection

- 5. Public health interventions save lives

- 6. Public health across the whole of society and built environment

- 7. Radon action can be cost effective

- 8. Health equity

- 9. Environment and sustainability

- 10. Climate action and health

- 11. Avoiding legal liabilities

- 12. Conclusion

Summary

Radon is a naturally occurring radioactive gas, emanating from the ground, entering and accumulating in buildings. Radon gas is found in every building in Canada at some level. Radon exposure is the leading cause of lung cancer after smoking, and accounts for an estimated 16 percent of lung cancer deaths in Canada. Radon mitigation methods are available and relatively inexpensive to reduce radon exposure in buildings and therefore reduce the number of radon attributable deaths. Despite these statistics, public awareness remains low and a vast majority of Canadian households (>90%) have not tested for radon. The Government of Canada has established the National Radon Program through Health Canada, but jurisdiction over buildings, public health, and air quality largely fall to provincial and territorial governments. Municipalities and regional districts also have powers to protect health and the environment and can jumpstart action on radon before, or in parallel, with higher levels of government. To encourage action on radon, Health Canada has created a Radon Action Guide for Provinces and Territorial, and for Municipal governments.

This document provides the justifications for municipal radon action, drawing on principles from law, policy, and bioethics, and marshalling evidence to show why radon action is important.

Radon action fits with widely accepted goals and objectives of public health, consumer protection, and environmental governance. Canadians look to their governments to ensure health needs are being met, and action on radon is a way to help people avoid unnecessary risks and save lives. Canadians feel strongly that consumers should be protected against damaged, faulty, and dangerous goods and services. These values can extend to homes and workplaces to ensure Canadians do not buy or rent homes that have high radon. Canadians feel strongly about environmental protection, and radon action is a way to ensure everyone lives in a healthy environment. Radon reduction action is a cost-effective intervention-in many cases investing in radon testing and mitigation will cost less as a way to save lives or improve quality of life than what the Canadian medical system routinely spends on many surgeries and drugs.

Radon can and should be included as part of climate and energy efficiency strategies-not only to protect against the risk that energy retrofits increase radon exposure, but to ensure that climate and human health goals are aligned. There are also existing legal obligations governments may already have-as landlords and employers-and which point to high radon creating potential liabilities.

Several existing municipal strategies and frameworks could be extended to include radon. These include chronic disease and cancer prevention strategies, sustainability planning and Healthy Built Environment frameworks. Including radon in these larger initiatives can be an important way to gain awareness of the issue and take initial steps to addressing the problem.

1. Introduction

Radon gas is a naturally occurring radioactive gas that emanates from the ground and can enter and accumulate in buildings. In Canada, radon exposure is the second leading cause of lung cancer after smoking, and accounts for an estimated 16 percent of lung cancer deaths.Footnote 1 Radon mitigation methods are available and relatively inexpensive to reduce long-term radon exposure in buildings and therefore reduce the number of radon attributable deaths.Footnote 2 Despite these statistics, public awareness remains low and a vast majority of Canadian households (>90%) have not tested for radon.Footnote 3 The Government of Canada, through Health Canada, has a National Radon Program, but jurisdiction over buildings, public health, and air quality largely fall to provincial and territorial governments. Municipalities and regional districts also have powers to protect health and the environment and can jumpstart action on radon before, or in parallel, with higher orders of government. Provinces and territories have made some positive steps such as changes to Building Codes, but there has been very little in the way of focused radon strategies or new legislation. This stands in contrast to many states in the United States of America (U.S.A) which have specific radon legislation, and the European Union where the Basic Safety Standards Directive requires member states to engage in radon planning.Footnote 4 In response, Health Canada has prepared a Radon Action Guides for provincial-territorial governments, and a Radon Action Guide for municipalities, and other local governments.

In this document, Health Canada outlines the policy rationales and ethical principles that support taking action on radon. This document will show how action on radon fits with widely accepted goals and objectives of public health, consumer protection, and environmental governance. Canadians look to the public health systems to intervene when lives can be saved. An estimated 29,300 Canadians contract lung cancer each year, and approximately 21,000 Canadians will die from lung cancer (about 1 in 15 people). Footnote 5 Radon is linked to approximately 3,360 deaths per year, more than 1 in 100 deaths in Canada.Footnote 6 An estimated 7% of homes in Canada have radon levels above Health Canada's Guideline of 200 Bq/m3. Reducing the number of homes with high radon, and in doing so the incidence of radon-induced lung cancer, fits with broad public health principles. Recognizing the important work that provinces, territories, and municipalities are already taking, the goal of this document is to present policy principles that can support radon reduction action and how a principled approach could lead to new interventions. Also included are broader environmental and health strategies, and frameworks that could easily be extended to incorporate radon action.

2. Radon is a unique issue

In 2007, the Canadian Radon Guideline was reduced from 800 Bq/m3 to 200 Bq/m3 and the National Radon Program was established to educate and encourage action to reduce indoor radon exposure. Health Canada's National Radon Program (NRP) has made significant strides in educating the public and key stakeholders about radon, conducting research to better understand the radon situation in Canada, and establishing the Canadian infrastructure and required resources to take action, test and mitigate, to reduce indoor radon. Significant challenges remain with respect to convincing Canadians to use the existing resources, adopt radon reduction behaviour change, and take action.

Decades of attention towards reducing tobacco use has reaped considerable success, now more focus can be placed on radon- the leading cause of lung cancer for non-smokers. Canadians now, more than ever, expect to have knowledge required to improve their health outcomes.

The risk from indoor radon exposure occurs largely in homesFootnote 7, making it a more challenging issue. For owner occupied homes, there are long standing beliefs of privacy and freedom from government interference. For rentals, many Canadian cities have very low vacancy rates, and high rental costs. The result is that standards of maintenance and health concerns in rental housing can be sidelined.Footnote 8 Privacy and access to affordable housing are important values, but should not negatively impact actions to reduce the health risk that radon poses.

Radon is 'naturally occurring', with the added assumption that it is therefore no one's responsibility. This is often accepted implicitly, but there are examples where it becomes a justification for inaction. For instance, the Construction Performance Guide for New Home Warranty in Alberta, explicitly mentions radon. However, it states that it is naturally occurring, and that radon entering the home does not amount to a defect, and that no warranty coverage is provided.Footnote 9 Radon ingress and accumulation is the result of how homes are built, and can be significantly reduced during the construction of a new home or through radon mitigation in existing homes. No one would take seriously the argument that a leaky roof was justified because rain was a naturally occurring phenomena. Just as Building Codes and landlord tenant laws ensure roofs keep out rain, doing nothing about radon is not a neutral position. Government policy can help ensure that health needs are being met.Footnote 10

3. Avoiding personal risks

Members of the public generally identify lung cancer as the result of smoking, and so see it as something that people bring on themselves. This means that people often put it aside as a worry, not seeing themselves as fitting a stereotype of a person at high risk.Footnote 11 However, radon-induced lung cancer in non-smokers is a real threat, and many Canadians are taking on significant risk unknowingly.

Health Canada research estimates that with lifetime exposure at a 200 Bq/m3 the radon-induced lung cancer risk is approximately 2% for non-smokers and 17% for smokers. At a high radon level of 800 Bq/m3, the lung cancer risk is estimated to be 5% (1 in 20) for non-smokers and 30% (3 in 10) for smokers, significantly higher than the baseline lung cancer rate of 1% (1 in 100).Footnote 12

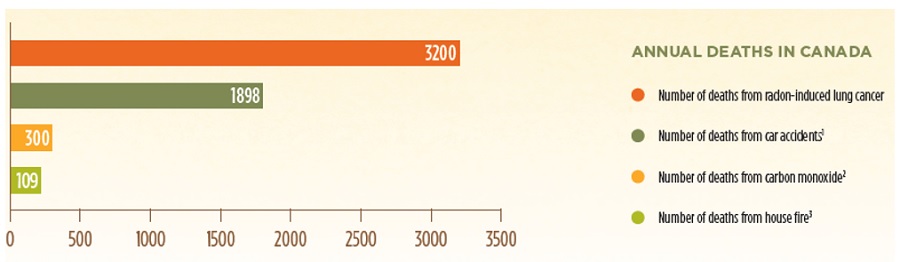

Canadians look to the government to help manage risk. The risk from exposure to radon can be much higher than Canadians accept from other better known hazards such car accidents, house fires or carbon monoxide poisoning (CO). Radon-induced lung cancer is linked to over 3,000 deaths annually, more than car accidentsFootnote 13, CO poisoningFootnote 14, and house firesFootnote 15 combined.

Annual Deaths in Canada

Description Figure:

The bar chart illustrates how radon-induced lung cancer compares to other health concerns. The annual death rate in Canada from exposure to radon-induced lung cancer is 3,200 deaths, higher than car accidents 1,898 deaths, carbon monoxide 300 deaths and house fires 109 deaths combined.

Provincial, Territorial, and municipal regulations, policies, and outreach programs on these issues have led to important behavior change such as, wearing seatbelts, and installing smoke and CO detectors in homes, which have resulted in a significant decrease in deaths.

4. Consumer protection

Canadians feel strongly that consumers should be protected against damaged, faulty, and dangerous goods and services. These values can extend to homes and workplaces. There exist requirements that spaces must be safe or in good repair, such as in landlord-tenant law, employment standards, or occupier's liability (the area of law that covers 'slip and falls'). Consumer protection principles also underlie the duties of professionals, who generally are under duties to operate with care and skill, and to serve the interests of the clients. Many existing laws and professional duties that very generally cover indoor safety can also apply to radon. Governments, administrative agencies, and professional bodies can provide guidance and clarification on how existing laws apply to radon reduction in homes.

One area where consumer protection principles have proven to be effective in radon policy is in the area of real estate. A long-standing principle of property law is that a seller needs to disclose to buyers any significant defects in the property that cannot be detected in a normal property inspection. Real estate licensees are under a duty to report known latent defects to buyers, as well make investigations relevant to the interests of their clients. In 2011, a legal decision in Quebec stated that high radon could be a latent defect.Footnote 16 Since that time, real estate councils, commissions, and associations across Canada have started to issue bulletins and education to members around radon.Footnote 17 In Ontario, elevated radon in new homes can be covered under new home warranty legislation.Footnote 18

5. Public health interventions save lives

Radon action is a key way to prevent disease before it arises, and so fits into the established mandate of public health systems. Many of the most substantial advances in improving health have come through non-medical developments such as improving housing and sanitation, ensuring clean water and sewer systems in cities, health and safety regulations, and vaccination programs.Footnote 19 A preventive approach is enshrined in international documents such as the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (1986), which calls on governments to take measures to reduce the risk of disease and prevent new cases of chronic disease from occurring. All Canadian provinces have public health administrations and many have overall guiding frameworks and strategies.Footnote 20 For instance, Ontario's Chronic Disease Prevention Guideline, 2018 provides guidance to local health boards on programs to reduce the occurrence of key diseases through addressing risks and promoting protective factors.Footnote 21 These could easily be amended to highlight radon as an important cause of lung cancer.

Some public health agencies have begun to look at radon. In Alberta, Health Services has ordered radon mitigation in rental accommodation, drawing on general clauses in the Public Health Act to address dangers to public health.Footnote 22 In one case in Calgary, inspectors responded to a renter's complaint, worked with the renter to complete tests and ordered the landlord to mitigate. In British Columbia, the Interior Health Authority has had an ongoing program of working with childcare providers. In 2014, health officials began a program of mailing free test kits to 800 childcare providers. In 2017, they went further, taking the novel step of ordering childcare facilities to test for radon.Footnote 23 The Ontario Public Health Standards sets out requirements for public health programs and services to be delivered by Ontario's 36 boards of health. Revisions in 2018 called for boards to prioritize radon.Footnote 24 As a result, many boards have begun community radon testing initiatives and public outreach.Footnote 25 Health units in Grey Bruce, ONT, Kingston, ONT, Thunder Bay, ONT, and others have adopted radon policies. Actions have included conducting community testing, expanded outreach, strengthening tobacco cessation programs, subsidizing test kits, and working with municipalities to implement radon provisions in the Building Code and permitting process.Footnote 26

In the 1990s, there was a widespread movement to restrict and ultimately ban smoking in public spaces. Many cities and local governments have public health bylaws that restrict smoking. These have been expanded to other areas, such as recently restricting the use of pesticides.Footnote 27 It is a natural step to extend the protection of clean air and public health to include radon. Indoor public spaces can be can regulated to ensure they are free from high radon concentrations.

6. Public health across the whole of society and built environment

Public health practitioners recognize that for many health problems broad organizational and social change are needed. In what is called a "socio-ecological model of health" attention is directed not only at individual behaviour, but broader social and work networks, wider communities, and longer term and entrenched social positions. Health improvements come not only from educating people, but can also include financial incentives, and legal change, such as requirements for seatbelts, or forms of community building and empowerment, such as supporting patient groups and including them in public consultations.Footnote 28 "Whole of Society" approaches are oriented towards coordinating activities throughout the whole of government to ensure policy does not become siloed-and often use long-range visions and plans.Footnote 29 "Health in All Policies" seek to understand how systems work together, to make use of synergies and avoid harmful health impacts.Footnote 30 These point to radon action extending beyond the confines of public health agencies to involve intergovernmental cooperation and strategic planning to bring change to the many institutions and organizations that govern and manage indoor spaces.

Many of these trends have coalesced in 'Healthy Built Environment' frameworks. These recognize that the human made environment can have significant health outcomes. Decades of city building have created cities that are suboptimal for health-for instance with automobile dependence and decreased physical activity. Alternatively, a health lens can help drive better planning and design that can overcome silos and use systems thinking across many areas-planning for communities that facilitate walking and physical activity, planning for recreational green space to protect mental health, separating housing from polluting truck routes, or ensuring all residents can access healthy food. Many Canadian cities have adopted "Healthy City" and "Healthy Community" strategies, which applies a health lens across diverse city functions and programs, coordinate diverse departments, and develop a longer-range strategic plan.Footnote 31 These can also involve memoranda of understanding or other forms of coordination between local health authorities and municipal planners.Footnote 32

Some healthy community strategies and guides already give attention to radon, or include broader themes, which can include radon. Often they shine the light on unhealthy indoor air,Footnote 33 promote green building initiatives that include attention to indoor airFootnote 34 or more generally link the quality of housing to health.Footnote 35 British Columbia's Healthy Built Environment Linkages Toolkit directs cities to promote ventilation and building design to address radon and to consider radon when siting, zoning, and permitting housing developments.Footnote 36 Radon can and should be a part of built environment strategies.

7. Radon action can be cost effective

For many homeowners, radon testing is an inexpensive investment. There are many testing devices and services available across Canada, simple home test kits are available for purchase for approximately 50 dollars. Radon mitigation professionals typically charge between $ 2,500-3,000 for retrofitting radon reduction systems in existing houses, and the costs are much less when worked into initial building design and construction for new buildings.Footnote 37 A 2015 study by Health Canada demonstrated that radon mitigation methods are very effective and commonly reduce radon levels by 80-90%, even where pre-mitigation radon levels exceeded 1,000 Bq/m3.Footnote 38 Canadian researchers have also shown that it makes good economic sense for governments to support broader programs of testing and mitigating homes in higher radon regions.

Public health is oriented towards maximizing well-being, and over time, a series of techniques have been developed to estimate the costs and expected results, in order to prioritize potential interventions.Footnote 39 Cost effectiveness analysis seeks to estimate the cost of a drug, technology, program or intervention in terms of expected results. Typically, a Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY) is used as the expected benefit so that the cost effectiveness represents not only how long lives are extended, but also the health, or quality of experience, of the persons whose lives are extended by the intervention. Health systems will typically use threshold figures of $50,000 Canadian dollars (for the United Kingdom) and $65,000 Canadian dollars (for the United States) per QALY.Footnote 40 The World Health Organization has recommended similar figures to assess the value for money. If the cost effectiveness of an intervention is less than the threshold, it becomes an economic argument for the health system to adopt it.Footnote 41 Radon testing and mitigation has been found to be a cost effective intervention for many countries.Footnote 42 This suggests that governments-especially in countries with publicly financed medical systems- could fund radon programs in the same way they might fund new equipment in hospitals.

Canadian researchers have also found radon interventions can be effective in many cities in Canada.Footnote 43 Installing radon preventive measures including "radon rough-ins" at the time of construction is cost effective across the country. Testing and retrofit mitigation of older homes with concentration above 200 Bq/m3 can be cost effective in some places.

In some cities, such as Vancouver, current evidence suggests that very few buildings have high radon. This means that most tests reveal negative results and so it becomes relatively expensive to find high radon homes and fix them. However, in cities where a higher percentage of homes have high radon, the costs of testing to find each high radon home falls. Programs for testing and retrofitting existing housing with radon over 200 Bq/m3 were found to be cost-effective in some cities including Halifax, St. Johns (NB), Quebec City, Sherbrooke, Montreal, Ottawa-Gatineau, Kingston, Windsor, Winnipeg, Saskatoon, Regina, and Kelowna. Provincial level data pointed to retrofitting being cost effective throughout Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, the Northwest Territories, and the Yukon.

8. Health equity

Canadians care deeply about equality of access to health care. This is a special case of the broader principle of health equity, which is also central to public health and population health. Health equity means that all people can reach their full health potential and should not be disadvantaged from attaining it due to social position or other socially determined circumstances (such as gender or race).Footnote 44 Health equity involves the fair distribution of resources needed for health, fair access to the opportunities available, and fairness in the support offered to people when ill.Footnote 45 Improving the health outcomes of the whole population often requires focusing on the needs of less advantaged populations.Footnote 46

Ideally, health equity will be part of radon promotion and policy development. Renters, low-income persons, social housing, and new immigrants need to be included in community radon programs. Many people are not in a position to make important decisions about the spaces they inhabit; with this in mind, relevant law and policy frameworks might be considered when addressing radon to support outcomes that protect everyone. For instance, local geology plays an important role in determining the likelihood of elevated radon. Smaller towns and rural areas can have radon problems just like urban centres, but they may not have radon mitigators, residents may earn lower wages, and communities may have less access to centralized decision-making.Footnote 47 Extra effort may be required on the part of governments to make sure that resources are available to those who need them.

Health equity supports targeted interventions that aim to improve health outcomes for particular groups. Many Canadians will have limited economic means and be forced to put off investing in radon mitigation in order to meet immediate needs for food or utilities. One solution could be a program that provides reduced cost or free test kits and mitigation subsidies or rebates.

9. Environment and sustainability

Since industrialization in the nineteenth century and the resulting urban pollution, the connection between health and environment have been well known. Our societies now depend on frameworks of environmental laws that seek to limit airborne pollutants and toxic chemicals to safeguard human health. In some cases, this takes the form of more comprehensive strategies and action plans to protect humans through improving air quality, and reducing pollutants.Footnote 48 Traditional environmental law targeted polluting industries but over time have come to encompass broader aspects of the environment. For instance, there are many laws, regulations and standards to protect the air inside people's homes from pollutants that might arise from consumer products such as glues and paints.Footnote 49 In pursuing clean air, environmental health policies often do come with broad objectives such as 'reducing rates of lung cancer'Footnote 50, which can be further drivers of radon action. Ontario's Health Standards thus target natural and built environments, including indoor pollutants, and particularly mention radon.Footnote 51 Ontario also gives specific direction to health boards to work with municipalities to promote healthy built and natural environments to enhance population health and mitigate environmental health risks. It directs health boards to consider local bylaws covering areas such as property standards, housing conditions, temperature, pests and vermin, and fire smoke.Footnote 52

As environmental issues have become more complex and intertwined with economic and social issues, many governments have brought in broad sustainability policies. Especially at the city level, these often feature a very diverse range of initiatives meant to drive environmental improvement, ranging from improving public transit and drawing containment boundaries to stop sprawl, to increasing home water and energy efficiency. Some cities have included radon in such plans. In Thunder Bay, Ontario, early testing by the health authority led to radon action being incorporated in the City's EarthCare Sustainability Plan 2014-2020. The plan draws on extensive citizen and stakeholder engagement through 11 working groups in thematic areas of energy, green building, land use planning, climate adaptation, education, food, mobility (active transportation, transit, walkability), waste, air, community greening, and water. Radon mitigation is stated as an important action item. The City has followed the plan and conducted a radon monitoring study within the city and made radon testing a condition of obtaining occupancy permits in new homes.Footnote 53

Many governments in Canada have also declared a right to a healthy environment. This principle holds that every Canadian - no matter who they are, or where they live -should enjoy a minimum standard of environmental quality. To date, 174 municipalities have passed declarations supporting the right to a healthy environment, including major cities such as Victoria, Vancouver, Montreal, Yellowknife, Hamilton, St. Johns Newfoundland, Windsor and Halifax, Toronto, and Ottawa.Footnote 54 When we think of healthy environments as a right, we do not draw firm boundaries at the edge of people's homes, but take the steps to ensure that everyone is living in an environment that promotes good health.

Recognizing a right to a healthy environment also implies taking steps to ensure that the provision of environmental programs be equitable. We know, however, that the environmental burden of disease is not equitably distributed among Canadians. Vulnerable individuals and communities bear a disproportionate share of the burden of pollution and other environmental hazards and receive an inadequate share of access to environmental amenities, benefits, and resources.Footnote 55 Some populations, such as renters, may also be disproportionately exposed to other contaminants that effect lung health. For instance, smoking, more prevalent in low-income groups, has an additive effect with radon, and a majority of lung cancer deaths from radon will be among smokers.Footnote 56 Community consultation and attention to the needs of specific groups, helps ensure programs are accessible for members of many communities. In the United States, where for many years the main emphasis was on homeowner education,Footnote 57 many organizations have sought to bring environmental justice perspectives to bear on radon policy, using it, for example, as a basis to move beyond consumer choice to require Building Code changes,Footnote 58 or to emphasize local decision-making.Footnote 59

10. Climate action and health

There is a growing recognition by international organizations and governments that climate change is a significant health issue, such as with extreme heat related stress, increased incidence of diseases, or forest fire and smoke events.Footnote 60 A health lens can also be shone on climate change mitigation and adaptation planning and this is a common feature of healthy built environment initiatives. Climate change mitigation efforts aimed at greenhouse gas emissions reduction can also achieve health outcomes. For instance, compact, walkable communities can reduce automobile use and greenhouse gas emissions; switching from internal combustion to electric engines can decrease traffic related air pollution; and ensuring access to local food can ensure nutrition while also reducing energy intensive 'food miles'.Footnote 61

Radon reduction should be a part of climate action. There are many ways that changing building design can have unexpected outcomes. Building retrofits that make houses 'tight' in the name of energy efficiency can also increase radon levels, and as a result, there is a trend towards higher radon levels in new homes.Footnote 62 As well, outdoor events, such as fire smoke, can lead people to keep windows closed, and so forego natural ventilation. Alternatively, some energy efficiency initiatives include radon mitigation and radon mitigation can be designed in ways that are more energy efficient.Footnote 63 Homes can also be designed with ventilation systems that can address multiple indoor air problems and so overall improve health.Footnote 64 Governments can consider incorporating radon reduction into efficiency and retrofit programs and rebate programs.

11. Avoiding legal liabilities

There are many areas of law in Canada that impose general duties to ensure spaces are safe and these will apply to governments in their own operations. As well as being employers, many governments are direct providers of housing, and as such are subject to landlord-tenant laws and occupier liability laws.

Employers have broad duties to ensure the health and safety of their workplaces.Footnote 65 These general duties can be interpreted in light of the federal Natural Occurring Radioactive Materials (NORM) Guidelines, which translate to ensuring work spaces are under 200 Bq/m3.Footnote 66 Many provinces incorporate threshold limits for toxic chemicals set by the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists, which includes radon.Footnote 67 Some provincial workers compensation agencies do highlight radon. Footnote 68

Under occupier liability law, if a building owner or landlord does not take adequate steps to ensure the building is safe, a tenant or a visitor to a building who is harmed can sue in court for compensation.Footnote 69 Occupiers have been found liable for damages caused by omissions such as failing to install smoke alarms,Footnote 70 failing to install handrails on stairs,Footnote 71 poor lighting,Footnote 72 and unsecured planters.Footnote 73 It is possible that in the future renters and employees who suffer from lung cancer will be able to prove this was caused by high radon environments they have lived and worked in.

Landlords are also responsible under residential tenancies (or landlord-tenant) laws to ensure the spaces they rent are in good repair and offer quiet enjoyment to tenants. In Ontario and Quebec, tribunals have found renters should be protected from high radon levels.Footnote 74

Since 2007, the federal government has been testing its buildings for radon.Footnote 75 Many provinces also have policies to test for radon in their buildings, including social housing. For instance, approximately 2,000 public buildings have been tested in Nova Scotia, including all public schools. Footnote 76

Local governments also have duties related to inspection and enforcement of building codes. Once a local government makes the policy decision to inspect building plans and construction, it owes a duty of care to person who might be impacted. Courts have thus found cities liable when inspectors failed to find design and construction flaws.Footnote 77 Some provinces and local governments have put limits on municipal liability and there should be investigation into local rules.Footnote 78

12. Conclusion

As the Radon Action Guides will discuss, there are many ways that provinces and local governments can take action on radon. This document provides the reasons why governments can and should take action and includes a variety of individual policy rationales that can be considered on their own or combined where appropriate. For instance, most people do not only seek to save lives, but also care that programs are just and inclusive. When developing Provincial/Territorial or Municipal radon programs incorporate diverse values, have overlapping rationales, and use existing health strategies and frameworks within which radon action fits. In many cases, radon action will be more successful if grouped with other concerns as part of broader public health and environmental agendas. The principles that justify radon action are also principles that Canadian governments already adopt and which motivates considerable existing health and environmental legislation.

Footnotes

- Footnote 1

-

Chen, J., Moir, D. and Whyte, J., 2012. Canadian population risk of radon induced lung cancer: a re-assessment based on the recent cross-Canada radon survey. Radiation protection dosimetry, 152(1-3), pp.9-13.

- Footnote 2

-

Health Canada, 2012 Cross Canada Survey of Radon Concentrations in Homes, Final Report. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/environmental-workplace-health/reports-publications/radiation/cross-canada-survey-radon-concentrations-homes-final-report-health-canada-2012.html

- Footnote 3

-

See Statistics Canada, 2017. Knowledge of radon and testing. Table: 38-10-0086-01.

- Footnote 4

-

For US laws, see Environmental Law Institute, 2019. Database of State Indoor Air Quality Laws. Database Excerpt: Radon Laws. Available at https://www.eli.org/sites/default/files/docs/2019_radon_with_cover_bolded.pdf

European Union Basic Safety Standards Directive.96/29/Euratom. Available at http://www.ensreg.eu/nuclear-safety-regulation/eu-instruments/Basic-Safety-Standards-Directive - Footnote 5

-

Canadian Cancer Society, 2020. Lung Cancer. available at https://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-type/lung/statistics/?region=pe

- Footnote 6

-

Based on Statistics Canada measures of 283,706 deaths in 2018. See Deaths by Month https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310070801

- Footnote 7

-

Chen, J. 2019. Risk Assessment for Radon Exposure in Various Indoor Environments. Radiation Protection Dosimetry, 185,2, 143–150.

- Footnote 8

-

Phipps, E. 2018. Towards Healthy Homes for All: RentSafe Summary and Recommendations. Rentsafe Canada. Available at https://rentsafecanada.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/rentsafe-summary-report_final.pdf

- Footnote 9

-

Construction Performance Guide for New Home Warranty in Alberta. Available at http://www.municipalaffairs.alberta.ca/documents/2015_09_01_Performance_Guide.pdf at p. 327

- Footnote 10

-

Nuffield Council on Bioethics (2007) Public health: ethical issues. Available at https://www.nuffieldbioethics.org/assets/pdfs/Public-health-ethical-issues.pdf p. vxi

- Footnote 11

-

Renner, B., Gamp, M., Schamlze, R, and Schupp, H. 2015. Health Risk Perception. International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences. Elsevier.

- Footnote 12

-

Chen, J., 2016. Lifetime lung cancer risks associated with indoor radon exposure based on various radon risk models for Canadian population. Radiation protection dosimetry, 173(1-3), pp.252-258.

- Footnote 13

-

Canadian Motor Vehicle Traffic Collision Statistics: 2016. Available at https://tc.canada.ca/en/road-transportation/statistics-data/canadian-motor-vehicle-traffic-collision-statistics-2016

- Footnote 14

-

Carbon Monoxide Poisoning Hospitalizations and Deaths in Canada. Available at https://cjr.ufv.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Carbon-Monoxide-2017-Final-.pdf

- Footnote 15

-

Fire-related deaths and persons injured, by type of structure. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3510019501

- Footnote 16

-

Pouliot c. Leblanc 2011 QCCQ 7882 citng Quebec Civil Code, art. 1726

- Footnote 17

-

Real Estate Council of Alberta, 2019. Radon Information Bulletin. Available at https://www.reca.ca/wp-content/uploads/PDF/Radon.pdf; van Ert, A. 2019. REALTORS®and Radon: Protecting Buyers and Sellers. British Columbia Real Estate Association. September 23, 2019. Available at https://www.bcrea.bc.ca/practice-tips/realtors-and-radon-protecting-buyers-and-sellers/; RECBC, 2019. Radon and Your Professional Responsibilities. Report from Council: A Newsletter for Licensees in BC. Available at https://www.bcfsa.ca/industry-resources/real-estate-professional-resources/knowledge-base/report-council/report-council-newsletter-october-2019 see also CAA Quebec, "Radon in the House: Legal Questions", https://www.caaquebec.com/en/at-home/advice/tools-and-references/radon-in-the-house/legal-questions

- Footnote 18

-

Tarion, 2020. Radon and Your Warranty. https://www.tarion.com/media/how-your-new-home-warranty-protects-you-against-dangers-radon-gas

- Footnote 19

-

Nuffield Bioethics Council, 2007. ibid. at p. xv; Nixon, S., Upshur, R., Robertson, a., Benatar, S., Thompson, A., and Daar, A. 2008. Public Health Ethics, in Bailey, T, Caulfield, T, Ries, N. (eds). Public Health Law & Policy in Canada, Second Edition. LexisNexis. at p. 42

- Footnote 20

-

BC's Guiding Framework on Public Health https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/about-bc-s-health-care-system/health-priorities/bc-s-guiding-framework-for-public-health; Alberta's Strategic Approach to Wellness https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/2638ad48-04b5-4bd6-b347-2a2a63a1cf03/resource/937b3839-be43-49d8-a2ce-4e1566b62534/download/6880410-2014-albertas-strategic-approach-wellness-2013-2014-03.pdf; Preventing and Managing Chronic Disease: Ontario's Framework. available at https://sustainontario.com/custom/uploads/2011/06/Preventing-and-managing-chronic-disease.pdf

- Footnote 21

-

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, 2018. Chronic Disease Prevention Guideline, 2018. Available at https://files.ontario.ca/moh-guidelines-chronic-disease-prevention-guideline-en-2018.pdf;

- Footnote 22

-

See Public Health Act, RSA 2000, c. P-37 s. 59 to 61, and the Nuisance and General Sanitation Regulation, Alta Reg 243/2003, using "Nuisance" defined as "a condition that is or that might become injurious or dangerous to the public health, or that might hinder in any manner the prevention or suppression of disease" (Public Health Act, s. 1(ee)). Further discussion in Quastel et al ibid. at p. 86.

- Footnote 23

-

Using the Community Care and Assisted Living Act, S.B.C. 2002, c. 75 which empowers medical health officers to attach terms and conditions to a license (s. 11) and to revoke licenses if there is a risk to persons in the care of such facilities (s. 14). Further discussion in Quastel, et. al. ibid. at p. 93

- Footnote 24

-

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care, 2018. Ontario Public Health Standards: Requirements for Programs, Services, and Accountability. Available at https://www.ontario.ca/page/ontario-public-health-standards-requirements-programs-services-and-accountability

- Footnote 25

-

See Take Action on Radon, 2020. Ontario. at https://takeactiononradon.ca/ontario/

- Footnote 26

-

Every Home in Grey-Bruce Should Test for Radon Available at https://www.publichealthgreybruce.on.ca/Your-Environment/Healthy-Housing/Radon; KFL&A Health Unit, Radon. https://www.kflaph.ca/en/health-topics/health-hazards.aspx#Radon; City of Kingston, 2020. Radon Gas Mitigation. at https://www.cityofkingston.ca/resident/building-renovating/radon-gas-mitigation; Thunder Bay District Health Unit, 2019. Radon. Available at https://www.tbdhu.com/radon

- Footnote 27

-

City of Vancouver Health Bylaw No. 9535

- Footnote 28

-

Burris, S.C., Berman, M.L., Penn, M.S. and Holiday, T.R., 2018. The new public health law: a transdisciplinary approach to practice and advocacy. Oxford University Press. pp. 76-84

- Footnote 29

-

BC Healthy Living Alliance, 2014, On The Path To Better Health, available at https://www.bchealthyliving.ca/wp-content/uploads/bchla-path-final-mar14-screen.pdf, at p. 14

- Footnote 30

-

Meili, R. 2012 A Healthy Society: How a Focus on Health can Revive Canadian Democracy. Purich at p. 33

- Footnote 31

-

City of Vancouver, Healthy City Strategy. Available at https://vancouver.ca/people-programs/healthy-city-strategy.aspx; City of Kelowna. Healthy City Strategy. Available at https://www.kelowna.ca/our-community/planning-projects/current-planning-initiatives/healthy-city-strategy; Healthy Toronto by Design, 2011. https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/9621-TPH-healthy-toronto-by-design-report-Oct04-2011.pdf. Also see Alberta Healthy Communities Initiative. Available at https://albertahealthycommunities.healthiertogether.ca/about/alberta-healthy-communities-initiative/; Ontario Ministry of Health. 2009 Planning by Design: a healthy communities handbook. https://ontarioplanners.ca/OPPIAssets/Documents/Calls-to-Action/Healthy_Communities_Handbook.pdf Canadian Institute of Planners, Healthy Community Practice Guide https://www.cip-icu.ca/healthy-communities/

- Footnote 32

-

See for example, British Columbia's PlanH, implemented by BC Healthy Communities Society, which facilitates local government learning, and partnership development between health authorities and municipalities. https://planh.ca

- Footnote 33

-

Duhl, L.J., Sanchez, A.K. and World Health Organization, 1999. Healthy cities and the city planning process: a background document on links between health and urban planning (No. EUR/ICP/CHDV 03 04 03). Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/EUR-ICP-CHDV-03-04-03 p. 11

- Footnote 34

-

See Miro, A. and Siu, J. 2009. Creating Healthy Communities: Tools and Actions to Foster Environments for Healthy Living. Smart Growth BC. Available at https://planh.ca/resources/publications/creating-healthy-communities-tools-and-actions-foster-environments-healthy at p. 47; Canadian Institute of Planners, Healthy Communities Practice Guide. Available at https://bchealthycommunities.ca/resource/healthy-communities-practice-guide-0/ page 43 and p. 47; New York City Department of Design and Construction, 2016. Design and Construction Excellence 2.0: Guiding Principles https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/ddc/downloads/DDC-Guiding-Principles-2016.pdf at p. 11

- Footnote 35

-

City of Vancouver, 2014. A Healthy City for All. Vancouver's Healthy City Strategy. 2014-2025 Phase 1. https://council.vancouver.ca/20141029/documents/ptec1_appendix_a_final.pdf

- Footnote 36

-

BC Centre for Disease Control. 2018. Healthy built environment linkages toolkit: Making the links between design, planning and health, Version 2.0. Vancouver, BC: BC Provincial Health Services Authority http://www.bccdc.ca/health-professionals/professional-resources/healthy-built-environment-linkages-toolkit at p. 34, 52, and 71

- Footnote 37

-

Take Action on Radon, 2019. Reducing Radon. Available at https://takeactiononradon.ca/protect/reducing-radon/

- Footnote 38

-

Health Canada, 2018. Residential Radon Mitigation Actions Follow-Up Study, page 5. available at https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/publications/health-risks-safety/residential-radon-mitigation-actions-follow-up-study/27-1968-Public-Summary-Radon-EN2.pdf

- Footnote 39

-

Nixon, S., Upshur, R., Robertson, a., Benatar, S., Thompson, A., and Daar, A. 2008. Public Health Ethics, in Bailey, T, Caulfield, T,, Ries, N. (eds). Public Health Law & Policy in Canada, Second Edition. LexisNexis. at p. 47

- Footnote 40

-

Converting to Canadian dollars from Neumann, P.J., Cohen, J.T. and Weinstein, M.C., 2014. Updating cost-effectiveness—the curious resilience of the $50,000-per QALY threshold. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(9), pp.796-797 and Woods, B., Revill, P., Sculpher, M. and Claxton, K., 2016. Country-level cost-effectiveness thresholds: initial estimates and the need for further research. Value in Health, 19(8), pp.929-935.

- Footnote 41

-

WHO's Choosing Interventions that are Cost-Effective project (WHO-CHOICE) suggested that "interventions that avert one DALY [disability-adjusted life-year] for less than average per capita income for a given country or region are considered very cost-effective (see Bertram, M. et al. 2016. Cost-effectiveness thresholds: pros and cons Bulletin of the World Health Organization 94:925-930 available at https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272010 Canada's GDP in 2018 was $59,879 Global Affairs Canada, Annual Economic Indicators. https://www.international.gc.ca/economist-economiste/statistics-statistiques/annual_ec_indicators.aspx?lang=eng

- Footnote 42

-

World Health Organization, 2009. WHO handbook on indoor radon: a public health perspective. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547673

- Footnote 43

-

Gaskin, J., Coyle, D., Whyte, J., Birkett, N. and Krewksi, D., 2019. A cost effectiveness analysis of interventions to reduce residential radon exposure in Canada. Journal of Environmental Management, 247, pp.449-461.

- Footnote 44

-

c.f. Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, 2018. Ontario Public Health Standards: Requirements for Programs, Services, and Accountability available at https://www.ontario.ca/page/ontario-public-health-standards-requirements-programs-services-and-accountability at p. 20

- Footnote 45

-

National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health. (2013). Let's Talk: Health equity. Antigonish, NS: National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, St. Francis Xavier University. http://nccdh.ca/images/uploads/Lets_Talk_Health_Equity_English.pdf

- Footnote 46

-

Powers, M., Faden, R.R. and Faden, R.R., 2006. Social justice: the moral foundations of public health and health policy. Oxford University Press, USA.at p. 82)

- Footnote 47

-

For instance, in British Columbia radon levels are generally low in Metro Vancouver, and Vancouver, but some in some towns such as Castlegar, close to half of homes have been found to have radon levels above Health Canada Guidelines. See Donna Schmidt Lung Cancer Prevention Society, 2017. Lessons From Castlegar. Presentation 25 April 2017, CARST National Radon Conference Banff, Alberta. Available at https://carst.ca/resources/Conference%202017/Presentations%202017/Radon%20Presentation%20CARST%202017%20-%20castlegar.pdf

- Footnote 48

-

Boyd, D. 2015. Cleaner, Greener, Healthier: A Prescription for Stronger Canadian Environmental Laws and Policies. UBC Press, at p. 107; United States Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/environmental-health; European Union, 7th Environment Action Programme. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/environment/action-programme/

- Footnote 49

-

Hazardous Products Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. H-3

- Footnote 50

-

See, for instance, United States Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Objective C-2 at https://wayback.archive-it.org/5774/20220414131934/https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/cancer/objectives

- Footnote 51

-

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long term Care, 2021. Ontario Public Health Standards: Requirements for Programs, Services, and Accountability available at https://files.ontario.ca/moh-ontario-public-health-standards-en-2021.pdfSee Healthy Environments, pp. 34-36

- Footnote 52

-

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long term Care, 2018. Healthy Environments and Climate Change Guideline, 2018 available at https://files.ontario.ca/moh-guidelines-healthy-environments-climate-change-en-2018.pdf

- Footnote 53

-

Thunder Bay, 2014 - 2020. Earthcare Sustainability Plan available at https://www.thunderbay.ca/en/city-hall/resources/Documents/EarthCare-SustainabilityPlan_WEB_SECURE.pdf; For radon testing see Thunder Bay Health Unit at https://www.tbdhu.com/radon.

- Footnote 54

-

This was backed by the Blue Dot Movement, a project of the David Suzuki Foundation. A complete list of municipalities is available at https://davidsuzuki.org/project/blue-dot-movement/

- Footnote 55

-

Boyd, ibid. at p. 66

- Footnote 56

-

Lantz, P.M., Mendez, D. and Philbert, M.A., 2013. Radon, smoking, and lung cancer: the need to refocus radon control policy. American journal of public health, 103(3), pp. 443-447.

- Footnote 57

-

For environmental justice based criticisms of US policy see Edelstein, M.R. and Makofske, W.J., 1998. Radon's deadly daughters: science, environmental policy, and the politics of risk. Rowman & Littlefield. at p 217

- Footnote 58

-

Oregon Health Authority, 2011. Impact of environmental exposures in Oregon: Radon health risks available at https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/HEALTHYENVIRONMENTS/HEALTHYNEIGHBORHOODS/RADONGAS/ Documents/RadonInOregon.pdf; United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2020. Environmental Justice: Indoor Air Quality and Community-Based Action. For a longer discussion of environmental justice and radon in the United States see Edelstein, M.R. and Makofske, W.J., 1998. Radon's deadly daughters: science, environmental policy, and the politics of risk. Rowman & Littlefield. at p. 217

- Footnote 59

-

United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2020. Environmental Justice: Indoor Air Quality and Community-Based Action available at https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-08/documents/Environmental-Justice-Indoor-Air-Quality-and-Community-Based-Action.pdf

- Footnote 60

-

World Health Organization, 2019. WHO Health and Climate Change Survey Report: Tracking Global Progress. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/who-health-and-climate-change-survey-report-tracking-global-progress; Health Canada, 2008. Human Health in a Changing Climate: A Canadian Assessment of Vulnerabilities and Adaptive Capacity available at https://cdn.dal.ca/content/dam/dalhousie/pdf/faculty/science/emaychair/Reports%20Section/Emay_HumanHealthChangClim.pdf

- Footnote 61

-

PlanH, 2020. Healthy Built Environment. https://bchealthycommunities.ca/take-action/healthy-built-environment/

- Footnote 62

-

Shrubsole, C., Macmillan, A., Davies, M. and May, N., 2014. Unintended consequences of policies to improve the energy efficiency of the UK housing stock. Indoor and Built Environment, 23(3), pp.340-352 Arvela, H., Holmgren, O., Reisbacka, H. and Vinha, J., 2013.Review of low-energy construction, air tightness, ventilation strategies and indoor radon: results from Finnish houses and apartments. Radiation protection dosimetry, 162(3), pp.351-363.

- Footnote 63

-

Milner, J., Hamilton, I., Shrubsole, C.,Das, P., Chalabi, Z., Davies, M. and Wilkinson, P., 2015. What should the ventilation objectives be for retrofit energy efficiency interventions of dwellings?. Building Services Engineering Research and Technology, 36(2), pp.221-229.

- Footnote 64

-

Levasseur, M.E., Poulin, P., Campagna, C. and Leclerc, J.M., 2017. Integrated management of residential indoor air quality: A call for stakeholders in a changing climate. International journal of environmental research and public health, 14(12), p.1455.

- Footnote 65

-

For example see BC: Occupational Health and Safety Regulation, BC Reg 296/97, Part 4 - General Conditions - 296/97 at s. 4.1 Nova Scotia: Occupational Health and Safety Act, SNS 1996, c 7 s. 13(1)

- Footnote 66

-

Ontario has issued guidelines to this effect, see Ontario Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development, 2016. Radon in the workplace available at https://www.labour.gov.on.ca/english/hs/pubs/gl_radon.php

- Footnote 67

-

for instance for Nova Scotia see Workplace Health and Safety Regulations, made under Section 82 of the Occupational Health and Safety Act, S.N.S. 1996, c. 7 O.I.C. 2013-65 (March 12, 2013, effective June 12, 2013), N.S. Reg. 52/2013. At section 2.3.

- Footnote 68

-

Worksafe BC, 2020. Radon at https://www.worksafebc.com/en/health-safety/hazards-exposures/radon; Worksafe Alberta, 2015. Radon in the Workplace: Occupational Health and Safety Bulletin. Available at https://ohs-pubstore.labour.alberta.ca/rad007; Worksafe Saskatchewan, 2017. Radon Gas. Available at http://www.worksafesask.ca/prevention/environmental-risks/radon-gas/

- Footnote 69

-

Occupiers Liability Act R.C.B.C 1996, c. 337 s. 6 (1)

- Footnote 70

-

Bueckert v. Mattison (1996), 1996 CanLII 6701 (SK QB) Daniels v. McKelvery, 2010 MBQB 18, Leslie v. S & B Apartment Holding Ltd., 2011 NSSC 48

- Footnote 71

-

McLeod v. Yong, 1999 BCCA 249

- Footnote 72

-

Zavaglia v. MAQ Holdings Ltd. (1986), 1986 CanLII 919 (BCCA), 6 B.C.L.R. (2d) 286 (C.A.)

- Footnote 73

-

Klajch v. Jongeneel et al., 2001 BCSC 259, affirmed (on this point) Klajch (Guardian ad litem of) v. Jongeneel, 2002 BCCA 14 (CanLII)

- Footnote 74

-

CET-67599-17 (Re), 2017 CanLII 60362 (ON LTB); Duff Conacher c. National Capital Commission, file 22-051117-006G; 22-060118-001T-060227 decision of 28 September 2006, Barak c. Osterrath, 2012 CanLII 150609;; Bonin c. National Capital Commission, 2013 CanLII 122747 (QC RDL); Pickard c. Arnold, 2015 CanLII 129833; Bramley c. Vanwynsberghe, 2017 QCRDL 11313 For broader rulings on indoor air quality see Y.A., Y.E., S.A. & B.A. v Regina Housing Authority, 2017 SKORT 75, upheld Regina Housing Authority v Y.A., 2018 SKQB 70

- Footnote 75

-

Radon Testing in Federal Buildings – Highlights. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/environmental-workplace-health/radiation/radon/radon-testing-federal-buildings-highlights.html

- Footnote 76

-

See Radon Results For Public Buildings Available available at https://novascotia.ca/coms/noteworthy/Radon.html; CAREX Canada, 2017. Radon in schools: A summary of testing efforts across Canada. Available at https://www.carexcanada.ca/en/announcements/radon_in_schools/

- Footnote 77

-

Rothfield v. Manolakos [1989] 2 S.C.R. 1259; Just v. British Columbia, 1989 CanLII 16 (SCC), [1989] 2 SCR 1228; Ingles v. Tutkaluk Construction Ltd., 2000 SCC 12 (CanLII), [2000] 1 S.C.R. 298

- Footnote 78

-

For instance, In British Columbia, the Local Government Act allows municipalities to have bylaws allowing for the inspection plans, and not structures, so long as the plans have been approved by certified engineers or architects. Local Government Act, RSBC 2015, c 1 s. 742 and 743; In Ontario, the Building Act creates a system of "registered code authorities" which allows municipalities to avoid liability; however municipalities have not, generally made use of such authorities to avoid liability. See Building Code Act, 1992, SO 1992, c 23 s. 31 for discussion see Stoddard, D. 2017. Building Liability: Covering All the Bases. Paper presented to The Canadian Institute's 23rd Annual Provincial/Municipal Government Liability, February 7, 2017 available at http://www.canadianinstitute.com/provincialmunicipal-government-liability/wp-content/uploads/sites/1828/2017/02/Stoddard_930AM_day1.pdf

Page details

- Date modified: