Taking stock of progress: Cannabis legalization and regulation in Canada

Table of content

- Introduction

- We want to hear from you

- Scope of this engagement paper

- Background and context

- Discussion areas

- Final word

Introduction

With the coming into force of the Cannabis Act (the Act) on October 17, 2018, the Government of Canada legalized and strictly regulated the production, distribution, sale, import and export, and possession of cannabis for adults of legal age. Canada is the first major industrialized country to provide legal and regulated access to cannabis for non-medical purposes, signalling a shift away from the reliance on prohibitive measures to deter cannabis use, and the adoption of an evidence-informed public health and public safety approach.

During the Act's development, it was widely recognized that effective implementation of the new legislative framework would require ongoing monitoring to assess early impacts, and flexibility to adapt and respond to emerging policy needs. For this reason, section 151.1 of the Cannabis Act mandates a review of the Act to start three years following its coming into force, and that a report outlining findings or recommendations be tabled in both Houses of Parliament no later than 18 months after the launch of the review.

A review of the Cannabis Act

The Minister of Health and the Minister of Mental Health and Addictions have launched a review of the Cannabis Act. Pursuant to the Act, the objective of this review will be to assess its impacts on public health, including:

- the health and consumption habits of youth

- Indigenous persons and communities, and

- the cultivation of cannabis plants in a dwelling-house

In addition, the review will assess progress made towards achieving the purposes of the Act. Specifically, the review will focus on assessing the seven key objectives set out in section 7 of the Act:

- protect the health of youth by restricting their access to cannabis

- protect youth and others from inducements to use cannabis

- provide for the licit production of cannabis to reduce illegal activities in relation to cannabis

- deter illegal activities through appropriate sanctions and enforcement measures

- reduce the burden on the criminal justice system in relation to cannabis

- provide access to a quality-controlled supply of cannabis

- enhance public awareness of the health risks associated with cannabis use

The legislative review will also include an evaluation of patients' reasonable access to cannabis for medical purposes in light of cannabis legalization for non-medical purposes, including the role of personal and designated cannabis production.

We want to hear from you

The Government of Canada has engaged extensively with the public and stakeholders on various aspects of the cannabis regime, both in the development and implementation of the legal framework. As an extension of ongoing engagement efforts, public, partner and stakeholder views are being sought to inform the review of the Cannabis Act. This includes perspectives and evidence related to the Act's impacts to date.

This document presents an overview of key features of the legislative framework, outlines national trends and offers evidence related to the implementation of the framework. It also asks a series of key questions to solicit feedback from the public, partners, and stakeholders. Where possible, respondents are encouraged to provide evidence to support their responses. Stakeholders are invited to provide responses via the online questionnaire by November 21, 2022.

Scope of this engagement paper

Data presented in this paper was collected from a number of sources, including population surveys, data sets, and surveillance tools administered by Health Canada, other federal departments and agencies, as well as peer reviewed academic research. Priority has been placed on data that is national in scope.

Existing surveys

There are a number of public health surveys used by the Government of Canada to monitor and evaluate the impact of legalization and regulation of cannabis.

- Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTADS): A biennial survey, conducted by Statistics Canada from 2013-2017. The survey included Canadians aged 15 and older

- Canadian Alcohol and Drugs Survey: A continuation of CTADS, conducted by Statistics Canada, beginning in 2019 and containing many of the same questions as the CTADS. The survey includes Canadians aged 15 and older

- Canadian Community Health Survey: An annual survey addressing a wide range of health-related topics, conducted by Statistics Canada with Canadians aged 12 and older

- Canadian Cannabis Survey: An annual survey, conducted on behalf of Health Canada, which started in 2017. The survey includes Canadians aged 16 and older

- National Cannabis Survey: A survey initiated in 2018 to gather information on cannabis use and to monitor changes in behaviour following legalization of cannabis for non-medical use. The survey includes Canadians aged 15 and older

- First Nations Regional Health Survey: The first and only, national First Nations health survey which collects information to develop a detailed picture of the health and well-being of First Nations people living on reserve and in northern communities. The survey is conducted every 5 years and has included all age groups

- Indigenous Community Cannabis Survey: A survey developed to better understand the community strengths and knowledge of cannabis use and its impacts from the perspectives of Indigenous adults (age 18+) and youth (ages 12-17)

Provincial and territorial governments have flexibility to establish frameworks within their own jurisdiction to determine how cannabis can be sold, where stores can be located, and how stores must be operated. While the regulation of cannabis is a shared responsibility of the federal, provincial or territorial governments, the focus of the legislative review is on aspects of the framework within areas of federal jurisdiction and within the remit of the Minister of Health, who is responsible for the Cannabis Act, and the Minister of Mental Health and Addictions. In this regard, some policy issues related to the cannabis framework, including provincial frameworks governing distribution and retail sale, as well as drug-impaired drivingFootnote 1 and the excise tax framework, are not addressed within the scope of the legislative review and this document.

It is acknowledged that some stakeholders may wish to provide feedback related to the government's key priorities of strengthening economic growth, inclusiveness and fighting climate change. Relevant feedback will be shared with the appropriate departments as necessary.

A separate document, entitled Summary from Engagement with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples: The Cannabis Act and its impacts, has also been prepared to support engagement with, and gather feedback from, First Nations, Inuit and Métis in assessing the impacts of the Cannabis Act on Indigenous peoples and communities.

Background and context

From prohibition to a public health approach

Despite decades of prohibition and the use of criminal sanctions to deter cannabis use, prohibition failed to prevent a number of negative public health and safety outcomes. Cannabis use increased steadily year over year, becoming one of the most commonly used controlled substances in Canada. Canadian youth and young adults consumed cannabis at rates among the highest in the world. Individuals who came into contact with the criminal justice system faced negative and lasting consequences, which disproportionately affected marginalized and racialized people. People with criminal records often have difficulty in finding employment and housing, and may be prevented from travelling outside of Canada. Furthermore, organized crime profited immensely from the illegal sale of cannabis. The cumulative effect of these trends reinforced the need to adopt a new public health approach to minimizing the harms posed by cannabis.

Against this backdrop, in June 2016, the Government of Canada created the Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation to provide expert advice on key attributes of a new regime. Informed by the advice of the Task Force, in April 2017 the Government of Canada introduced Bill C-45, the Cannabis Act, in Parliament with the objective of keeping cannabis out of the hands of children and youth, and profits out of the hands of criminals and organized crime. Following extensive study and debate in both Houses of Parliament, the Cannabis Act received Royal Assent in June 2018.

The Cannabis Act and its regulations came into force on October 17, 2018, marking a new era in the Government of Canada's approach to cannabis control. During the first year that the Act was in force, legal sales were limited to dried cannabis, fresh cannabis, cannabis oil, cannabis plants, and cannabis seeds. On October 17, 2019, the sale of edible cannabis, cannabis extracts, and cannabis topicals was permitted, and the regulations were amended to include a suite of new controls to address the public health and safety risks associated with these products.

Discussion areas

Minimizing harms to protect Canadians

Minimizing harms associated with cannabis use is at the centre of the Government's objectives in pursuing a system of legal, regulated access to cannabis. The Cannabis Act introduces a suite of public health and public safety controls aimed at providing Canadians with evidence-based information to support informed decision-making, restricting youth from accessing cannabis and protecting children and youth from the harms associated with cannabis use.

The Act authorizes the production of a range of products, thereby enabling the legal industry to innovate and compete with the illegal market, and affording adult consumers comprehensive product choice. To reduce the risks associated with overconsumption and accidental consumption, limits have been placed on the quantity of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) that is permitted in certain cannabis products, by class of cannabis. Specifically, edible cannabis has a limit of 10 milligrams of THC per container, and cannabis extracts have a limit of 1000 milligrams of THC per container. However, to facilitate the legal industry's ability to compete with and displace the illegal market, there is no regulated limit to the amount of THC that may be contained in dried cannabis products.

Effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) & cannabidiol (CBD)

The cannabis plant contains hundreds of substances. Over 100 of these substances are known as phytocannabinoids. Phytocannabinoids are sometimes referred to by the more general term cannabinoids. All phytocannabinoids are regulated under the Cannabis Act and its regulations. The two most common are THC and CBD.

THC is responsible for the intoxicating effects of cannabis. THC has some therapeutic effects but it also has harmful effects, which may be greater when the potency of THC is higher, and can be affected by frequency of use and consumption method.

The potency (concentration or strength) of THC in cannabis is often shown as a percentage of THC by weight. THC potency in dried cannabis has increased from an average of 3% in the 1980s to around 15% today. Some products can have up to 90% THC.

Unlike THC, CBD does not cause people who use it to feel intoxicated or "high." However, there is evidence that CBD may have its own set of effects on the body and brain.

Recognizing that consumer choice and consumption are influenced by promotion and advertising strategies, the Act generally prohibits promotion of cannabis, cannabis accessories, or related services, except in specific circumstances to inform adult consumer choice. Limited promotion can be permitted in specific circumstances, subject to all applicable prohibitions. For example, the Act provides for informational promotion and brand-preference promotion, provided the promotion is addressed and sent to a named adult individual or in a place where youth are not permitted. Plain packaging and labelling requirements for cannabis products include limits on the use of logos, colours, and branding, as well as mandatory information that must be included (such as standardized cannabis symbol, health warning messages, THC and CBD content), and specific display formats about how product information must appear on the label. These measures aim to reduce the appeal of cannabis products to youth and others, while providing consumers with the information they need to make informed decisions before using cannabis.

Advertising and promotion restrictions have garnered significant attention and reactions from stakeholders over the course of implementation. While some stakeholders have advocated for less stringent promotion and packaging and labelling measures in order to permit better communication of information to consumers about product attributes, effects and composition, and to aid in competing against the illegal cannabis market, others have argued for maintaining existing measures in the interest of protecting public health and public safety, especially for youth. Evidence demonstrates that youth are particularly susceptible to brand imagery, and that the impacts of such imagery are especially pronounced. Footnote 2 There are significant health risks with cannabis that substantially increase for young persons under the age of 25 and people that use it frequently. Footnote 3,Footnote 4

Protective measures targeting children and youth

Targeted controls, such as child-resistant packaging and the required display of the standardized cannabis symbol on packaging, are in place to protect children and youth, who are especially vulnerable to experiencing adverse health effects from cannabis use. For youth who use cannabis frequently and over prolonged periods, it can be addictive, can affect brain development, may increase the risk of cannabis dependence, and could bring on or worsen disorders related to anxiety and depression. Footnote 5 For this reason, the Cannabis Act restricts access to cannabis for persons under 18 years of age. Provinces and territories have the flexibility to increase minimum age requirements in their jurisdictions. Most provinces and territories have set their minimum age at 18 or 19 to align with existing alcohol and tobacco access laws. The federal government's decision to set 18 years as the minimum age for the possession of cannabis took into consideration a number of factors including minimizing public health risks, the approach for other regulated substances such as alcohol and tobacco, and reducing the incentives for youth to access cannabis through the illegal market.

Promotion prohibitions in the Act

The Cannabis Act includes rules regarding the promotion of cannabis, cannabis accessories, and services related to cannabis, which are intended to completely prohibit:

- promotion that is appealing to youth

- promotion through any testimonials or endorsements

- promotion that presents a lifestyle (such as one that includes glamour, recreation, risk, excitement or danger)

There is substantial evidence indicating that promotional activities, particularly those targeting youth, can have a significant impact on the appeal, social acceptance, and "normalization" of a particular product, and, in turn, its level of use. Footnote 6 Informed by the experience in regulating other substances, in particular alcohol and tobacco, the Act imposes a range of measures to restrict youth from inducements to use cannabis. General restrictions on the promotion of cannabis, cannabis accessories, and services related to cannabis as noted above, include a complete prohibition on promotion that is appealing to youth. In addition, controls are in place to respond to harms that are a particular risk to children and youth.

Accidental ingestion of cannabis poses significant health and safety risks, especially for children. To mitigate this risk, the Act prohibits the sale of cannabis or cannabis accessories that have an appearance, shape, or another sensory attribute or function that appeal to youth. Cannabis products must be in plain packaging and must, other than for cannabis plants or plant seeds, be in a child-resistant container.

Evidence and trends: Attitudes and understanding of risk of cannabis consumption

The controls set out in the Cannabis Act aim to strike a balance in protecting public health and public safety while prioritizing consumer choice and providing adult consumers with the information they need to make informed choices about cannabis use. The 2021 Canadian Cannabis Survey (CCS) reports that 78% of respondents agreed (somewhat or strongly) that they have access to enough trustworthy information about the health risks of cannabis use to make informed decisions. There are several promising early signals that the framework's public health measures are supporting these efforts.

Promotion restrictions, plain packaging, and health warning messages help to reduce the appeal of cannabis for youth. Data collected through the International Cannabis Policy Study, which includes Canadian and American respondents aged 16 to 65, showed that brand imagery increased cannabis product appeal, whereas both plain packaging and health warnings reduced product appeal, particularly among youth. Data from this study has further shown that the level of awareness and knowledge of harms associated with cannabis use is greater among consumers living in jurisdictions where warning labels are mandated. Further, the ability of consumers to recall health warnings significantly increased in Canada between 2018 and 2020.Footnote 7

Although the proportion of respondents that report cannabis use as completely or somewhat socially acceptable is relatively unchanged since 2018, survey data is showing that attitudes amongst Canadians regarding the perceived risks of cannabis use have begun to shift, pointing to improved understanding of the potential health risks of cannabis use. Among past-year cannabis consumers, the proportion of those who believe regular cannabis use poses moderate or great risk rose from 40% to 50% for consumption by smoking, 34% to 40% for eating cannabis products, and from 38% to 55% for vapourizing cannabis. Footnote 8

Evidence and trends: Cannabis consumption patterns

Despite emerging evidence that perceptions of risk towards cannabis are starting to shift, this change in knowledge has not yet translated into a measurable change in Canadians' cannabis consumption patterns. Overall, usage rates continue to follow the upward trend that existed prior to legalization. The findings of both the 2019 Canadian Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CADS) and the 2020 Canadian Community Health Survey indicate that approximately one in five Canadians used cannabis at least once in the past year. There are differences in the prevalence of cannabis use according to sex, with males having higher rates of use than females. Footnote 9 Males are more likely than females to use cannabis on a daily or almost daily basis. Although a higher proportion of males are cannabis consumers and are more likely to become dependent, females typically progress more quickly to dependence or addiction. Footnote 10, Footnote 11, Footnote 12, Footnote 13,Footnote 14

While cannabis use remains higher among youth and young adults (those aged 15 to 24 years) than in older age groups, youth rates of use have not followed the uptrend observed in the general population and have remained relatively stable since the coming into force of the Cannabis Act. For example, the CADS found that 22% of 15-19 year olds reported past-year cannabis use, unchanged from the previous cycle.Footnote 15 It is encouraging to note that both the CCS and the CADS suggest that the average age of initiating cannabis use has slightly increased over time. According to the 2021 CCS, there is some promising data on the knowledge or beliefs regarding cannabis-associated harms by age groups; youth respondents (those aged 16 to 19 years) were found to be more knowledgeable on certain harms (such as risks of cannabis smoke, risks of developing mental health problems, and risks of using cannabis at a younger age) compared to older age groups (those aged 25 years and older).

Beyond the estimated number of Canadians that report using cannabis in the past year, the frequency of cannabis use is a key indicator to monitor when assessing the impacts of cannabis use on public health. Daily or near daily (five or more days per week) use of cannabis is strongly associated with adverse health outcomes, particularly related to mental health. Footnote 16, Footnote 17 The proportion of consumers of cannabis for non-medical purposes who report high frequency of use has remained stable over time. In line with survey results prior to 2018, about one quarter of past-year cannabis consumers report consuming five or more days per week. Among the general population, frequent use remains unchanged for youth populations; however, the prevalence of daily or almost daily use continues to be highest among young adults, with 1 in 10 of those between ages 20 to 24 using cannabis frequently. Footnote 18,Footnote 19

Smoking remains the most common method of consumption. The 2021 CCS found that 74% of consumers of cannabis for non-medical purposes reported smoking in the past year. However, results across a number of surveys point to a decline in smoking over time, as adult consumers shift away from traditional dried flower and hashish towards other products, such as edible and vaping products. Smoking remains highly prevalent among youth; for example, 86% of past-year users for non-medical purposes aged 16-19 in the 2021 CCS reported smoking. Beyond product choice, it is important to consider the factors that consumers take into account when choosing how and where to purchase their cannabis. The top three reasons influencing the source and type of cannabis purchased are: price (28%), safe supply (26%), and quality (14%). Footnote 20 Factors influencing cannabis purchasing patterns will be discussed later in this document.

Although the Cannabis Act has now been in force for over three years, caution is required when drawing definitive conclusions, either positive or negative, from the early trends presented above. The decades of investments and public education required to lower rates of tobacco smoking in Canada serve as a reminder that efforts to shift public attitudes and consumption patterns will take time. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted Canadians in numerous ways, which may have an effect on patterns of substance use in Canada. For example, the 2021 CCS asked specific questions about cannabis use changes due to COVID-19, and found that the majority of respondents (52%) used cannabis at the same frequency, while 27% reported using more frequently, and 21% reported using less frequently. The 2021 CCS also found increased rates of frequent use among younger age groups (aged 16-24) compared to individuals over age 25. Footnote 21 The most common reasons for increased cannabis use were boredom (62%), stress (60%), anxiety (55%), lack of a regular schedule (41%), and loneliness (37%). The most common reasons for decreased cannabis use were a lack of social gatherings or opportunities to socialize (34%), no specific reason (25%), and being too busy (14%). Cannabis use patterns are attributable to a range of factors, including social and economic determinants. This should be considered when attempting to draw cause-and-effect relationships between policy measures adopted, and trends observed since the coming into force of the Cannabis Act. The overview presented above is intended to help support and inform Canadians' feedback on the Cannabis Act. It represents only a small portion of the data that Health Canada is collecting and monitoring through various surveys and through partners, all of which is publicly available. For more information about cannabis use trends in Canada, refer to Cannabis research and data for more information.

Discussion questions

- What is your view of the current legislative and regulatory restrictions in place to safeguard public health?

- What controls, if any, would you like to see changed and why?

- Are the current safeguards, outlined above, adequately restricting access and helping to protect the health of youth?

- Under the current framework, what presents the greatest risk to youth in accessing and consuming cannabis?

- Are there additional sources of information or data that you believe should be considered to support the legislative review?

Education and awareness to support informed choices

Cannabis education and awareness is fundamental in achieving the public health and public safety objectives of the Cannabis Act. Federal public education and awareness activities have focused on providing youth and young adults, marginalized populations, Indigenous peoples and communities, and other populations at increased risk of experiencing harms related to cannabis use (for example, effects on pregnancy and breastfeeding), with factual information regarding the legislative framework, along with other clear and consistent evidence-based information about the health and safety risks of cannabis use. The goals of federal actions are to support informed choices, to build knowledge and influence risk perceptions, and ultimately to encourage lower-risk behaviours in relation to cannabis.

The Government of Canada's approach to cannabis education and awareness has been informed by its experience regulating tobacco as well as lessons learned from states in the U.S. that have legalized and regulated cannabis. These sources demonstrate that comprehensive and sustained public education and awareness efforts can be impactful in influencing risk perceptions and behaviours.

Public opinion research conducted on attitudes and perceptions prior to the legalization of cannabis highlighted that the Canadian public, including youth, lacked awareness of key public health and safety risks posed by cannabis use. For example, pre-legalization survey results show that of the respondents who used cannabis in the past 12 months, only 61% believed that cannabis use affects driving.Footnote 22, Footnote 23 In the development of the Act, stakeholders and Parliamentarians consistently expressed strong support for the intensification of public education and awareness efforts ahead of implementation, and the need to ensure that education and awareness activities were comprehensive, sustained and sufficiently resourced over time.

Education and awareness initiatives implemented to date include various evidence-based information tools, advertising and marketing campaigns, partnerships with non-governmental entities, and collaboration with the provinces and territories as well as Indigenous partners. Specific emphasis has been placed on reaching children and youth, as well as segments of the population at increased risk of cannabis use harms.

Cannabis education and awareness has focused on providing clear and consistent information regarding health and safety risks of cannabis use, travel prohibitions, and strict penalties for impaired driving. Investments of $108.5 million over six years (2017-2023) have supported national advertising and social media campaigns, extensive use of partnerships to complement and extend the reach of federal education and awareness efforts, and targeted educational resources for priority audiences, as discussed above, as well as travelers and visitors to Canada and Canadians in general.

Substance use and addictions program

Investments of $62.5 million over five years (2018-2023), directed through Health Canada's Substance Use and Addictions Program have supported the involvement of community-based organizations in the delivery of a national public education campaign to priority segments of the population, including:

- youth and young adults

- Indigenous populations

- pregnant and breastfeeding people

- older adults

- healthcare professionals

- Canadians in general

Program projects have supported delivering messages on the health risks of cannabis, including:

- harm reduction

- mental health impacts

- understanding the risks of driving while under the influence

- encouraging informed decision-making and health promotion

Evidence and trends

There are early signals suggesting that public education initiatives have been impactful in building awareness about the legislative framework, as well as health and safety information about cannabis. The Canadian Cannabis Survey (CCS) has shown incremental increases over the past three years in the percentage of respondents that felt they had enough trustworthy and credible information about cannabis. The survey also demonstrates improving trends when comparing general knowledge regarding cannabis-related risks before and after education and awareness campaigns. For example, among those who used cannabis within the past 12 months, 64% believed cannabis use could be habit forming in 2017, compared to 93% in 2021.

Among youth, data indicates that only a small minority (one in ten) of student respondents between grades 7 and 12 perceive there to be "no risk" associated with regular cannabis use. Risk perception of regular cannabis smoking in 2018-19 was similar to levels in the data collected in the 2014-15 school year. A substantially larger proportion of male versus female students endorse the view that there is no risk associated with regular cannabis use. Footnote 24

Despite a number of positive early signals in cannabis education and awareness efforts, recent evidence reinforces the need for sustained and ongoing investments in the areas of public education and awareness. Recently there has been a trend toward reduced exposure to cannabis health information. The percentage of respondents who reported seeing health warning messages on cannabis packages or products, or on the Health Canada website, declined from 38% in 2020 to 30% in 2021. The percentage of respondents who did not notice any education campaigns or public health messages increased from 24% in 2019 to 39% in 2021. Footnote 25

Declines in these trends could be partially attributed to the fact that a great deal of public education funding was used at the outset of legalization to ensure the Canadians were well-prepared and well-educated in advance of, and through the process of legalization, while the past two years have been focused on sustaining messaging about cannabis and its health impacts. However, efforts over the past two years were also overshadowed by recent unexpected public health events, most notably COVID-19, which has significantly dominated the public education space from a health perspective.

Discussion questions

- To what extent have public education efforts delivered the appropriate messages and reached the appropriate audiences, including youth and young adults?

- What additional measures or areas of focus could be considered to continue to close the gap between perception of risks and harms and scientific evidence?

- Are there additional sources of information or data related to education and awareness that you believe should be considered throughout this review?

Progress toward establishing a responsible supply chain

State of the legal cannabis market

Canada's approach to the legalization of cannabis was predicated on the establishment of a legal cannabis marketplace capable of providing adult Canadians with access to a quality-controlled supply of a diverse range of products. Oversight of the cannabis supply chain is a shared responsibility across federal and provincial and territorial governments, with involvement from industry, municipalities and other stakeholders. The federal government regulates the production of cannabis, while provinces and territories have oversight over wholesale cannabis distribution and retail sale within their jurisdiction. Health Canada has enacted a competitive private-sector production model, whereby a person is required to obtain a licence in order to conduct various activities with cannabis.

The licensing system is designed to enable a diverse, competitive legal industry comprised of both large and small players. The system allows for a range of different activities and aims to reduce the risk that organized crime will infiltrate the legal industry while facilitating the transition of illegal producers into the legal market.

Health Canada licensing categories

There are four broad categories of licences, permits, and authorizations, including:

- cultivation licences (standard, micro and nursery subclasses)

- processing licences (standard and micro subclasses)

- sales licences (federal medical sales licences)

- other licences and permits (industrial hemp licences, analytical testing, research, cannabis drug licences, and import or export permits)

Each licence authorizes a different suite of activities related to cannabis and stipulates to whom a licence holder may sell or distribute cannabis. Health Canada's policy does not limit the number of cannabis licences, with the expectation that the size and number of market participants would be determined by market forces.

A key feature of the licensing framework is distinct subclasses for micro-production to support the participation of small-scale growers and processors in the legal supply chain. Micro-licences have a maximum limit of 200 square metres of growing surface and a calendar-year possession limit of 600 kilograms of dried cannabis or its equivalent that has been sold or distributed to them, other than cannabis plants or seeds. They are also subject to lower fees and fewer physical security requirements than standard licence holders, proportionate to the decreased risk presented by smaller-scale activities.

There are many provisions within the Act to regulate the quality of cannabis produced by federal licence holders. These include Good Production Practices and cannabis product standards, such as testing requirements for microbial and chemical contaminants and adherence to Standard Operating Procedures. Adherence to such requirements is validated in a number of ways, including reporting and onsite inspections by Health Canada.

A national Cannabis Tracking System enables the tracking of the movement of cannabis across the country, with reporting on the activities of licence holders and provincially and territorially authorized distributors and retailers. The data collected through the System works with other regulatory measures to help prevent inversion of illegal cannabis into, and diversion of cannabis out of, the legal market. Health Canada publishes quarterly reports summarizing cannabis market data collected through the System.

Engaging a diverse cannabis industry

Health Canada launched the Licensing Micro Engagement Strategy to increase the number of micro-class licence holders and better support the transition of illegal producers into the regulated industry. The number of micro-licence holders has grown from around 20 at the start of 2020 to 340 as of July 31, 2022, comprising 38% of all federal licence holders.

Data from the Centre on Drug Policy Evaluation demonstrates that White males are over-represented in leadership positions in the Canadian cannabis industry, while racialized, Indigenous, and female individuals are greatly under-represented.

Health Canada has met with industry stakeholders to better understand how to support racialized and under-represented communities in the cannabis licensing program. This engagement has opened a dialogue on how the licensing program can evolve to better support existing and potential industry stakeholders representing racialized communities.

Home cultivation

Apart from the commercially-produced products available to adults in provincially and territorially authorized retailers, home cultivation provides an alternative means for adults to legally access cannabis. The Cannabis Act permits home cultivation, propagation and harvesting of no more than four plants per dwelling-house. There is no federal limit to how much cannabis (obtained from the plant or other legal source) an adult can store at home, and adults are permitted to share limited quantities of cannabis, including cannabis seeds and seedlings, with other adults; however, unless authorized, it is prohibited to sell cannabis.

Home cultivation was the subject of substantial debate during both the Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation's consultations and Parliamentary consideration of Bill C-45. Notably, concerns were raised regarding public health and safety (for example, electrical problems, fire, mould, break-ins, and theft), increased exposure of children to cannabis, challenges associated with oversight, and the potential for diversion to the illegal market. Proponents of home cultivation argued that once a legal, regulated supply of cannabis was available, there would be a decrease in the demand to produce illegal cannabis, and that those who chose to grow up to four plants could do so safely. Additionally, home cultivation would enable access to cannabis at a lower cost and to consumers living in rural and remote areas.

Evidence and trends

Collectively, the legal cannabis industry has been successful in providing adult consumers with consistent and reliable access to cannabis products. The expansion of available product classes, as well as ongoing growth in the number of licence holders and retail access points across Canada has provided adult consumers with access to a broad range of legal cannabis products.

As of July 31, 2022, there were 886 active federal commercial licence holders (for example, cultivation, processing and medical sales licences) located across all ten provinces, the Yukon, and Northwest Territories. From October 2019 to December 2021, licence holders reported $5.6 billion in total revenues, including sales to distributors, retailers, medical clients and other licence holders. Across Canada, approximately 3,200 retail stores have been authorized by the provinces and territories to sell cannabis. Additionally, online sales are available in each of the 13 provinces and territories, providing access to adults in regions that are geographically distant or lacking in brick-and-mortar retail stores.

At the outset of cannabis legalization in 2018, Canadians were generally paying a higher price for products in the legal market than for similar products obtained from illegal sources. However, the gap between legal and illegal prices is narrowing. The average price per gram of legal dried cannabis for non-medical purposes has fallen steadily since October 2019, reaching $5.66 in December 2021.Footnote 26

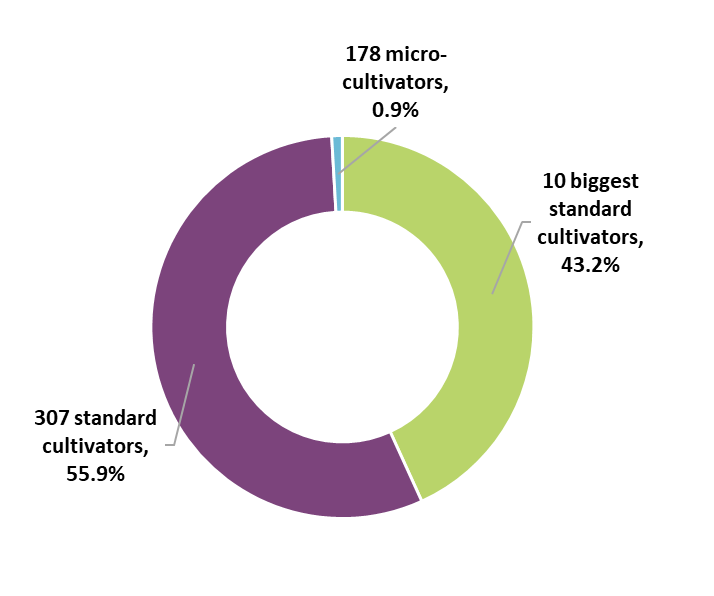

Cannabis production is not evenly distributed among licence holders. Between October 2019 and December 2021, 43.2% of dried cannabis production came from 10 standard licence holders, 55.9% came from another 307 standard licence holders, and the remaining 0.9% came from 178 micro-licence holders. Revenues reported to Health Canada reflect a similar trend, with ten parent companies accounting for 66% of all revenues, 33% accounted for by 200 additional parent companies representing other standard licence holders, and 0.3% attributed to 53 parent companies controlling micro-licence holders.

Figure 1 - Text description

| Cultivator type | Number of cultivators | Share of unpackaged dried cannabis production |

|---|---|---|

| Biggest largest standard cultivators | 10 | 43.2% |

| Remaining standard cultivators | 307 | 55.9% |

| Micro-cultivators | 178 | 0.9% |

The cannabis market is still in its infancy and is subject to ongoing market corrections. In response to downward pressure on wholesale prices, licence holders are seeking new investors and are restructuring in order to help them compete in an increasingly competitive market. Some licence holders are exiting the industry altogether or are reducing the number of sites they operate. A total of 95 cannabis licence holders exited the market between October 2018 and July 31, 2022. Footnote 27 This represents 9.7% of licences issued during that period. Of these, 15 were micro licence holders, 13 were sale for medical purposes only, and 67 were standard licence holders.

Evidence and trends: Home cultivation

Results from the 2021 Canadian Cannabis Survey (CCS) suggest that 57% of respondents who use cannabis purchase most or all of their cannabis from the legal market, with a relatively small proportion of consumers of cannabis for non-medical purposes sourcing their cannabis through home cultivation. According to the survey, less than 10% of past-year consumers of cannabis for non-medical purposes reported home cultivation as their "usual" source. Among those who reported plants grown in or around their residence, the average number of plants grown was 3.6.

There is little evidence to suggest that home cultivation of cannabis for non-medical purposes has resulted in an increase of illegal activity or diversion to the illegal market. Law enforcement, provinces and territories, and municipalities have expressed concern about production of cannabis for medical purposes, which, under the medical access program, is not subject to the four-plant limit per dwelling-house. Specifically, there is concern that some within the medical access program could be using their licence as a cover for the production and diversion of cannabis to the illegal market. More information regarding access to cannabis for medical purposes can be found in the section Access to cannabis for medical purposes.

Discussion questions

- Do adult Canadians have sufficient access to a quality-controlled supply of legal cannabis?

- What alternative measures, if any, could the government consider to further strengthen and diversify the legal market?

- What alternative measures, if any, could the government consider to better meet the needs of racialized, under-represented or Indigenous communities within the cannabis licensing program?

- To what extent have the current restrictions on home cultivation of four plants or less supported the safe and responsible production of cannabis?

- Are there additional sources of information or data related to the legal market or home cultivation for non-medical purposes that you believe should be considered throughout the legislative review?

Protecting public safety

Canada's approach to legalization includes a broad range of measures designed to protect public safety and to penalize those who operate outside the legal market, while at the same time reducing the burden on the criminal justice system. While the Cannabis Act provides strict penalties for serious cannabis offences, provisions are in place to divert minor offences outside of the criminal justice system.

Combating the illegal market

While the primary focus of the government's approach to combating the illegal market is to provide consumers with the ability to purchase cannabis from legal, regulated sources, it was understood that there would continue to be activity outside of the legal framework. The Cannabis Act provides law enforcement with the authority to take action against illegal cannabis activity.

Beyond criminal penalties for serious offences such as illegal production and sale, the Act and its regulations contain a number of provisions specifically designed to address the risk of inversion and diversion of cannabis to or from the illegal market. For example, the Cannabis Regulations require licence holders, key site personnel, and directors and officers of a corporation holding a licence for the cultivation, processing, or sale of cannabis to undergo a detailed background check by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to ensure that they have no affiliations with organized crime. This requirement helps to ensure that licence holders and other associated individuals do not pose an unacceptable risk to public health or public safety, including the risk of cannabis being diverted to an illegal market or activity.

Criminal Penalties in the Cannabis Act

In the Cannabis Act, penalties are set in proportion to the seriousness of the offence. Criminal offences related to unauthorized activities with cannabis include, but are not limited to:

- public possession of more than 30 grams of legal dried cannabis or its equivalent

- unauthorized distribution or sale of cannabis

- producing cannabis beyond personal cultivation limits

- producing cannabis with organic solvents

- taking cannabis across Canada's borders

- giving or selling cannabis to a person under the age of 18

- using a youth to commit a cannabis-related offence

Depending on the offence, penalties can range from fines, to jail time, or both, with the most serious offences, including giving or selling cannabis to a youth, subject to a maximum penalty of up to 14 years in jail. The Act does provide for the diversion of certain offences (for example, possession of five or six plants). Diversion proceedings or mechanisms for young persons under other laws may also be applicable, including under the Youth Criminal Justice Act.

Public possession limits

Consistent with the approach taken in other jurisdictions, the Act imposes a public possession limit of a maximum of 30 grams of dried cannabis or its equivalent for individuals over age 18. Equivalencies have been set out in the Act for the purposes of determining the personal possession limit for different classes of cannabis. For example, one gram of dried cannabis is equivalent to five grams of fresh cannabis, or 0.25 grams of cannabis concentrates (for example, high THC vaping cartridge).

Notwithstanding the objective to protect the health of young persons by restricting their access to cannabis, the Government of Canada recognized the significant harm that a criminal record for simple possession could have on youth. For this reason, the Cannabis Act contains no prohibition on youth possession or distribution of very small amounts of dried cannabis (up to five grams or its equivalent). Instead, provincial laws set penalties by way of tickets, similar to how jurisdictions address the possession of alcohol by minors.

Different views have been expressed in relation to whether there should be a limit on the amount of cannabis an individual can legally possess in public. During the development of the Act, many law enforcement officials argued in favour of possession limits, suggesting that such limits could be used as a tool to identify, investigate and prosecute individuals who may be engaging in illegal activity. Conversely, there was also strong opposition to the proposal, highlighting that there are no public possession limits on either alcohol or tobacco.

Evidence and trends: Progress toward reducing burden to criminal justice system

Early evidence points to a measurable impact in reducing Canadians' interactions with the criminal justice system in relation to cannabis. In 2017, when the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act was the mechanism for controlling cannabis, police reported approximately 47,000 incidents involving cannabis. In 2019, with the Cannabis Act in place, police reported approximately 16,000 incidents involving cannabis related to federal statutes (not including provincial non-criminal incidents).Footnote 28 Footnote 29

A recent study completed by the Canadian Centre for Substance Use and Addiction points to a dramatic reduction in the number of youth cannabis possession offences following legalization. Additionally, the percentage of youth possession cases involving a formal diversion out of the Court system has increased from 7.9% in 2015 to 21.2% in 2019.Footnote 30 Despite these positive trends, the authors point to the need for more study and analysis to better understand youth contact with the criminal justice system. In particular, they highlight further analysis is needed to better understand why, despite the overall reduction, youth cases were more likely to result in a criminal charge. For example, the percentage of possession incidents involving a young offender resulting in a criminal charge rose from 32.5% in 2015 (accounting for 3,819 incidents from a total of 11,754) to 45.5% in 2019 (accounting for 337 incidents out of 740).Footnote 31

While there has been a year over year decline in cannabis possession charges, law enforcement personnel continue to investigate cannabis-related incidents, whether under the Cannabis Act or under provincial laws governing access to, and distribution of, cannabis. A total of 28,794 incidents were reported in 2019 and 2020 under the Cannabis Act. Footnote 32 These incidents do not capture the additional resources that law enforcement personnel expend to enforce provincial non-criminal cannabis-related offenses, including fines and tickets.

It is important to recognize that there are significant disparities and systemic over-representation of both Indigenous peoples and vulnerable and marginalized people in the criminal justice system. Footnote 33 Academic studies have shown that Black and Indigenous people are largely found to be over-represented amongst those arrested for cannabis possession. Footnote 34 Work is underway by Statistics Canada to address the lack of systematic data available regarding racial disparity for cannabis-related offences.

First Nations leaders have also expressed growing concerns with illegal cannabis operations within their communities. In contrast to the observed decline in illegal cannabis storefronts in many municipalities, several reserves situated close to large urban centres report a growth in illegal storefront operations. Illegal activities have placed increased pressure on local leadership and policing resources. First Nations have indicated that space for recognition of community-based cannabis laws will help them meet the public health and safety goals they share with the federal government.

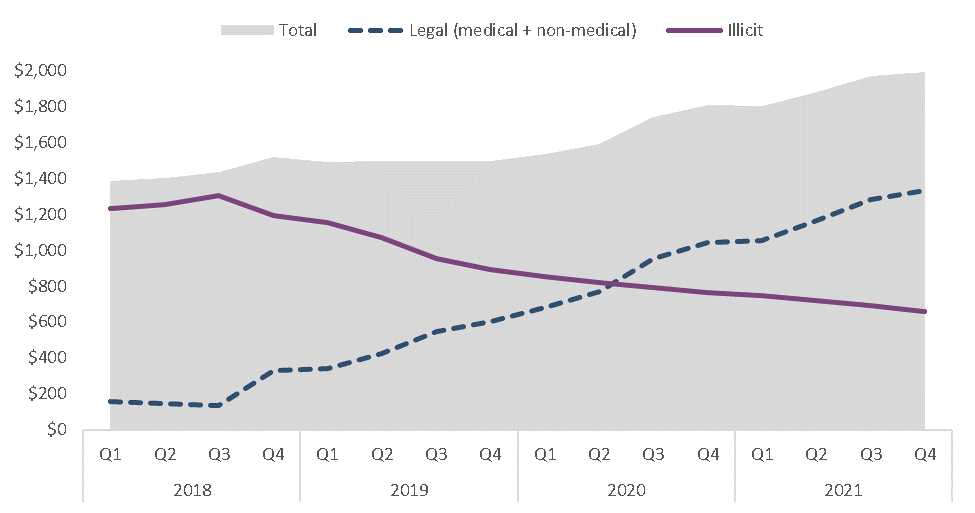

Evidence and trends: Disrupting the illegal cannabis market

Various surveys and estimates suggest that the growth of the domestic legal market has displaced illegal purchases of cannabis. Both the Canadian Cannabis Survey (CCS) and the National Cannabis Survey show an increase in the number of consumers who report accessing cannabis from legal sources and decreasing numbers who report access from illegal sources. Additionally, Statistics Canada's Household Consumption Expenditure table suggests that, at the national level, the legal share of the value of cannabis consumed has steadily increased, rising to 66% in the fourth quarter of 2021, compared to 9% prior to legalization. Footnote 35, Footnote 36 Estimates at the provincial level show a consistent trend. In 2021, following a review of its provincial cannabis legislation, Quebec's Ministry of Health and Social Services estimated that as much as 70% of people who consumed cannabis in the past 12 months purchased it from a legal source. Footnote 37 Similarly, a recent Ontario Cannabis Store Quarterly Report (October-December 2021) highlights that the legal share of the non-medical cannabis market in Ontario increased from 54.2% in the previous quarter to 58.5%.Footnote 38

Source: Statistics Canada Household Consumption Expenditure

Figure 2 - Text description

| Total Legal (medical + non-medical) | Illicit | Total (Legal + Illicit) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Q1 | 154 | 1232 | 1386 |

| Q2 | 147 | 1254 | 1401 | |

| Q3 | 133 | 1304 | 1437 | |

| Q4 | 328 | 1190 | 1518 | |

| 2019 | Q1 | 339 | 1152 | 1491 |

| Q2 | 426 | 1072 | 1498 | |

| Q3 | 544 | 954 | 1498 | |

| Q4 | 603 | 894 | 1497 | |

| 2020 | Q1 | 679 | 855 | 1534 |

| Q2 | 771 | 820 | 1591 | |

| Q3 | 951 | 789 | 1740 | |

| Q4 | 1043 | 763 | 1806 | |

| 2021 | Q1 | 1054 | 747 | 1801 |

| Q2 | 1163 | 720 | 1883 | |

| Q3 | 1281 | 690 | 1971 | |

| Q4 | 1333 | 660 | 1993 | |

Oversight and controls, such as record-keeping and reporting requirements, compliance promotion, and inspections of licensed sites, have proven successful in protecting the integrity of the commercial supply chain. Although there have been a small number of documented cases of diversion of cannabis out of the regulated market, these incidents were identified and promptly addressed. As of January 2022, six cannabis licences have been suspended, and three have been revoked for critical violations of the Cannabis Act, including diversion of cannabis out of the regulated market.

Despite the meaningful and sustained progress towards the displacement of the illegal market, there are particular areas of concern regarding illegal cannabis activity. The illegal drug market remains a source of profit for many organized crime groups. Statistics Canada's Household Consumption Expenditure table estimates consumption of cannabis from illegal sources was estimated to be $2.8 billion in 2021. Footnote 39 A recent research study indicates individuals who continued to purchase cannabis through illegal channels were more likely to be male, less likely to be college or university graduates, consumed cannabis more frequently, and agreed more strongly that illegal cannabis is cheaper and of higher quality and should not be regulated by the government.Footnote 40

In contrast to the notable decline of unlicensed brick and mortar stores operating in Canada, disrupting illegal online cannabis sales is an ongoing challenge. Policing online activity is complicated – a website can be created in one country, hosted in another, on a domain name registered in yet a third, while selling a product in multiple jurisdictions. Additionally, websites can be set up with ease, and can replace those that have been seized or shut down by law enforcement.

Illegal websites are particularly concerning from a public health perspective as they provide an easy pathway for youth to access cannabis. The products purchased illegally online do not abide by the requirements of the Act, including contaminant testing and requirements to accurately present the amount of THC in a product on the label. Many illegal websites directly market themselves using images and products that appeal to youth, including cannabis packaged to resemble candy of various brand names. These illegal operations offer one explanation for why youth do not perceive cannabis as difficult to access. Recent student surveys report that six out of 10 students in grades 10 to 12 report easy access to cannabis.Footnote 41

Finally, it is important to recognize that cannabis remains the most widely consumed drug, with an estimated 200 million people consuming globally in 2019. Footnote 42 Cannabis is produced in almost all countries worldwide. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime reports that the cultivation of the cannabis plant was reported by 151 countries, covering 97% of the global population. Footnote 43 Globalization and new technologies, such as mobile payments and digital currencies, have magnified the threat of transnational organized crime and drug trafficking.

Canada Border Services Agency's efforts

The Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) website was updated to specifically mention mail and courier environments in relation to online ordering of cannabis products.

CBSA is leveraging social media, for example, with tweets like this:

"Online shopping for #cannabis? Your shipment won't cross the border. Stick to Canadian retailers. Don't bring it in. Don't take it out."

International travelers, mail, courier, and commercial shipments continue to be subject to customs requirements and are examined for prohibited goods, including illegal cannabis. Data from the Canada Border Services Agency shows an increase in both the number and quantity of cannabis interdictions (importation and exportation). Between calendar years 2018 and 2021, there was a 114% increase in cannabis interdictions (10,728 in 2018 to 22,921 in 2021), and a 416% increase in the total quantity of cannabis interdicted (3,198 kilograms to 16,495 kilograms). Footnote 44 It is important to highlight that approximately 90% of all interdictions occurred on importation and have been largely attributed to unintentional violations of relevant legislation. While a small percentage (10%) of total border interdictions involving cannabis have been attributed to export, the majority are for larger quantities (over one kilogram) where there is intent to contravene legislation.

Discussion questions

- What are your general impressions of legal retailers’ progress to date in capturing the legal market? Please explain.

- What additional steps or measures should the government consider to combat the illegal cannabis market?

- Are there additional sources of information or data related to the criminal justice system that you believe should be considered throughout the legislative review?

Access to cannabis for medical purposes

Prior to the coming into force of the Cannabis Act, activities such as the possession, production and distribution of cannabis were generally prohibited in Canada. However, successive court rulings dating back to the late 1990s have recognized that the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms affords individuals the right to reasonable access to cannabis for medical purposes. Today, individuals who have an authorization from their health care practitioner can access cannabis for medical purposes by:

- registering with a federally licensed seller of cannabis for medical purposes, allowing individuals to purchase regulated cannabis products directly and have those products securely shipped to them

- registering with Health Canada to cultivate cannabis for their own medical purposes or designating someone to produce it on their behalf

- purchasing products directly, in store or online, from provincially or territorially authorized retailers

The Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation considered different perspectives regarding the need for a separate system to provide access to cannabis for medical purposes, in light of the legalization of cannabis for non-medical purposes. The emergence of a legal framework for access to cannabis for non-medical purposes was seen by many as a risk to medical access, products, and clinical research. Patients feared that absent a dedicated medical program, their ability to access cannabis for medical purposes could be compromised. Their concerns included potential supply shortages, risks that certain products would no longer be available due to producers shifting to supply other products for the larger non-medical market, and concern that there would be less incentive for industry to invest in clinical research.

Conversely, members of the medical community questioned the need to maintain a parallel system as the coming into force of the cannabis legislative framework would allow patients to access cannabis for medical purposes legally. Law enforcement and municipal representatives cautioned against continuing to permit personal and designated production given the risks that relatively large-scale grow operations could be permitted, and that production would be diverted to the illegal market.

Ultimately, the Task Force recognized that the legalization of cannabis for non-medical purposes would fundamentally change adults' access to cannabis – but acknowledged that the impact was too uncertain and unpredictable to support wide scale reforms, at the time, to the established medical access programs. Instead, the Task Force recommended that the Government review the medical access framework, following the coming into force of the Cannabis Act, to determine whether a separate regime is necessary to continue to maintain reasonable access to cannabis for medical purposes.

Evidence and trends

As of December 2021, there were approximately 299,000 registrations to access cannabis for medical purposes with either Health Canada or a federal medical sales licence holder. Of these, the majority of registrations (approximately 85%) are with federal medical sales licence holders. Patients registered with federally-licensed sellers have seen a marked increase in the number of suppliers and the diversity of cannabis products available to them. As of July 31, 2022, there are 135 licensed medical sellers who are permitted to sell a wide range of cannabis products to registered medical patients. These products range from dried cannabis to additional products that were not available prior to legalization, such as edible cannabis (for example, teas or chocolates), topicals (such as skin creams), and extracts (for example, vaping products or hash).

Since the Act came into force, the number of registrations with federally licensed sellers briefly increased, but is now lower than pre-legalization levels, going from 346,000 in October 2018 to 257,000 by the end of 2021. In line with published evidence and guidance about the use of cannabis for medical purposes, the average daily amount authorized by health care practitioners for individuals purchasing cannabis for medical purposes has remained relatively constant at 2 grams of dried cannabis per day since legalization.

Information for healthcare professionals

Health Canada has developed a peer-reviewed document, Information for healthcare professionals, which is intended to be used by healthcare professionals to support their decision-making with respect to cannabis for medical purposes. The document contains information on the pharmacology, dosing, potential therapeutic uses, precautions, warning, and adverse effects associated with cannabis and the cannabinoids.

Health Canada proactively shares data on the number of health care practitioners who authorize cannabis for medical purposes and publishes data on daily authorized amounts by jurisdiction, including amounts over 25 grams and 100 grams per day, thereby encouraging transparency and increased scrutiny of health care practitioners who regularly authorize high amounts.

As of July 31, 2022, Health Canada has refused or revoked 839 registrations, including refusing or revoking 270 registrations for reasons of public health and safety. Additional refusals and revocations may result as the department continues to review applications and registrations to ensure compliance with the Cannabis Regulations.

In contrast, the number of individuals who are registered with Health Canada to produce cannabis for their own purposes (or who designate another individual to do so on their behalf) has increased from approximately 26,000 individuals in October 2018 to 42,000 individuals as of December 2021. Health Canada has seen a progressive increase in the average daily amount being authorized for these individuals from an average of 25 grams per day in October 2018 to 44 grams per day as of December 2021 (which would allow a person to grow approximately 215 indoor plants).Footnote 45

As noted above, there is long-standing concern from law enforcement and local municipalities that some personal and designated production sites are being used to support organized crime and diversion to the illegal market. Footnote 46, Footnote 47 Health Canada works closely with law enforcement agencies to provide information on active cannabis investigations, on a 24/7 basis, through a dedicated police services line and collaboration on special projects. In 2020 and 2021, Health Canada responded to more than 2,800 requests for address searches to support investigations in Ontario and Quebec alone.

At the same time, patient advocacy groups, and long-standing community programs and compassion clubs cite that the separate medical system legitimizes cannabis use for medical purposes, prevents stigma, and maintains certain rights (for example, the ability to possess more cannabis in public based on authorization amount, up to a maximum of 150 grams of dried cannabis or its equivalent). They also point to the personal and designated production program as the sole viable option for accessing the quantity, quality, or variety of cannabis that individuals require for their medical purposes. The most common factor cited by patients and patient advocacy groups in support of the personal and designated production program as a route of access is the affordability of cannabis for medical purposes, compared to purchasing from a federally licensed seller.

Many Canadians report using cannabis for medical purposes outside of the medical access program. The most recent estimate from the 2019 Canadian Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CADS) suggests that among people who have used cannabis in the past year, 36% (an estimated 2.3 million) reported having used cannabis and attributed at least some of their cannabis use to treat or manage medical conditions (either with or without physician oversight). The top medical conditions for which people reported using cannabis include anxiety (28%), arthritis (18%), depression (7%), and other medical conditions (27%).

In addition, the production and sale of prescription drugs containing cannabis is authorized under the Food and Drugs Act and the Cannabis Act. Health Canada is currently exploring establishing a legal pathway for health products containing cannabis that would not require health care practitioner oversight. Consistent with other health products regulated by the Food and Drugs Act, the authorization to bring these products to market would be based on meeting manufacturing requirements, including safety, efficacy and quality standards.

Discussion questions

- What are your views on the current medical access program for cannabis?

- Is a distinct medical access program necessary to provide individuals with reasonable access to cannabis for medical purposes, or can access needs be met through the non-medical framework?

- Are there specific reforms that you would recommend?

- Are there additional sources of information or data related to the medical access program that you believe should be considered in the legislative review?

Engaging Indigenous partners to assess impacts of legalization

As highlighted in the Final report of the Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation, successful implementation of the government's approach to the legalization of cannabis requires a commitment to work in an ongoing partnership with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis governments and communities. Provincial and territorial officials who met with the Task Force saw close coordination on the development and implementation of the Cannabis Act as essential.

Engagement with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis governments and communities on the legalization of cannabis for non-medical purposes has continued throughout the development and implementation of the Act. As of August 2022, Health Canada officials have participated in over 280 engagement sessions with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis governments, communities and organizations across Canada to better understand their perspectives and concerns regarding cannabis legalization, share public health information related to cannabis, and to provide details about the Act.

Through engagement with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis representatives, Health Canada has heard specific interests and needs in the following areas:

- establish governance processes and supports to ensure that First Nations, Inuit, and Métis partners have voices in shaping the future direction of federal policies to meet shared objectives of the Cannabis Act

- culturally appropriate public education and mental health and substance use services

- First Nations, Inuit, and Métis jurisdiction over various aspects of cannabis activities

- increased participation in economic opportunities created by the cannabis market

- address challenges with ensuring public safety through appropriate enforcement tools and resources

For First Nations, Inuit, and Métis leaders, organizations and individuals, discussions about cannabis legalization are critically linked to broader issues such as self-determination, reconciliation, and economic and community development. Building on the results of prior federal engagement, the legislative review of the Cannabis Act will include a dedicated Indigenous engagement process with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.

A companion document, Summary from engagement with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples: The Cannabis Act and its impacts, has been prepared to facilitate targeted, distinctions-based engagement and to validate priority areas of focus specific to Indigenous governments and communities. Early engagement will help shape the lines of inquiry and priority areas for engagement with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis governments and communities over the course of the review.

Evidence and trends

As highlighted by Indigenous Services Canada's 2021 Annual Report to Parliament, it is important to acknowledge the gaps in data that mask inequalities and reduce the potential to develop effective policies that address existing socio-economic and health inequities.Footnote 48

Health Canada is taking steps to improve the quality and availability of data regarding the impacts of the Cannabis Act on Indigenous peoples and communities. Research conducted since cannabis legalization has focused on risks and potential benefits of cannabis use, including for mental health and wellness, as well as a focus on the perceptions of cannabis use and how those perceptions influence patterns of use amongst Indigenous populations. The growing Indigenous-led body of research and data collection is essential in helping to broaden the understanding of the impacts of the Cannabis Act on Indigenous peoples and communities.

The First Nations Regional Health Survey, Footnote 49 led by the First Nations Information Governance Centre, represents the first national survey implemented explicitly in keeping with the First Nations principles of ownership, control, access, and possession – more commonly known as OCAP®. Phase 3 of the study, conducted in 2015 and 2016, found cannabis to be one of the most frequently reported non-prescription substances used amongst First Nations adults (ages 18 years or older). Approximately 30% of First Nations adults indicated past-year use of cannabis, and 12% indicated daily or almost daily use.Footnote 50

There are gaps in the data available regarding cannabis use by First Nations, Inuit, and Métis in the period after cannabis legalization. The Thunderbird Partnership Foundation has collected information on cannabis use among Indigenous peoples in Canada through the regional dialogue sessions and the Indigenous Community Cannabis Survey, conducted from May to November 2018. Footnote 51 Two hundred and twenty-nine adults (ages 26 and older), and 27 youth (ages 18 to 25) completed the survey. Among adults, three-quarters of respondents indicated they had not used cannabis in the past year.

Data collected from national population surveys provide some insights into rates of cannabis use among people self-identifying as Indigenous. However, these surveys have limitations and exclusions that are of particular relevance to Indigenous peoples living in Canada. For example, national results may obscure important differences in patterns of cannabis use across regions and communities, and some survey designs exclude people living in northern territories or First Nations populations living on reserve. Notwithstanding these limitations, the overall results from the Canadian Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CADS) are generally consistent with the finding of the Regional Health Survey with regard to the extent of cannabis use. The CADS found that 30% of respondents self-identifying as a First Nations, Métis or Inuk (Inuit) person reported using cannabis in the past 12 months in 2019, which was unchanged from 27% in 2017. In this survey, past-year cannabis use was higher among First Nations, Inuk (Inuit), or Métis in both 2017 and 2019 than it was among people not self-identifying as Indigenous.

Results from the Canadian Cannabis Survey (CCS) also suggest that the prevalence of past-year use of cannabis for non-medical purposes was higher among those self-identifying as First Nations, Inuk (Inuit), or Métis than it was among the general population (39% and 25%, respectively, in 2021). The prevalence of past-year daily or almost daily non-medical use of cannabis was higher among those self-identifying as First Nations, Inuk (Inuit), or Métis, with 15% of self-identified Indigenous respondents reporting daily or almost daily use in 2021, as compared to 6% among those not identifying as Indigenous. The results of the 2021 CCS suggest the average age of cannabis use initiation among respondents self-identifying as Indigenous was 17.0 years, which was lower than the average age of 20.5 years among non-Indigenous respondents.

Recent research and data collection efforts have focused on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, as well as substance use patterns and perceptions among Indigenous peoples and communities. For example, a study conducted by Statistics Canada found that six in ten Indigenous participants reported that their mental health has worsened since the onset of the pandemic. Footnote 52, Footnote 53 The Canadian Mental Health Association conducted a study on the ongoing mental health impacts of the second wave of the pandemic and found reports of worsening mental health since the first wave, as well as higher rates of cannabis use as a coping strategy among Indigenous respondents (24%) than the rate amongst all survey participants (9%). Footnote 54, Footnote 55 These findings are consistent with the finding of the Thunderbird Partnership Foundation which has highlighted that First Nations peoples have cited stress, anxiety, the need to get high, and dealing with trauma as reasons for increased use of cannabis since the beginning of the pandemic.Footnote 56

While the findings outlined above do not provide a complete picture of how Indigenous individuals and communities have been affected by cannabis legalization, they do offer valuable insights on the broader trends of cannabis use among Indigenous peoples. Taken together, the studies suggest a greater risk of use of cannabis for non-medical purposes among Indigenous people in Canada and support First Nations, Inuit, and Métis emphasis for ongoing prevention and treatment initiatives, with community-engagement to inform their development.

As noted above, Health Canada has developed a companion document, Summary from engagement with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples: The Cannabis Act and its impacts, to support early engagement with Indigenous peoples as part of the Cannabis Act legislative review.

Final word

This document is intended to collect stakeholder perspectives and gather additional evidence to inform the legislative review of the Cannabis Act. However, Health Canada recognizes that the legalization of cannabis has had wide-ranging impacts on Canadian society that reach beyond the core public health and public safety objectives of the Act. This includes impacts on the Government of Canada's key priorities of strengthening economic growth, inclusiveness and fighting climate change. Pursuant to the Cabinet Directive on Regulation, it is important that Health Canada consider the impact its regulations have on the environment and small businesses, as well as the potential differential impact the regulations may have, based on sex, gender, or other identifiable grounds.

Discussion question

- What are your views on the impacts of legalization of cannabis on the environment, small businesses and social and economic impacts on diverse groups of Canadians, in accordance with the Government of Canada's commitment to implementing Sex- and Gender-Based Analysis Plus (SGBA+)?

As an outcome of this engagement process, Health Canada will make available a summary report providing highlights of input received. In addition, feedback provided will be considered in the assessment of the early impacts of cannabis legalization and will help to shape any findings or recommendations resulting from the legislative review.

We encourage respondents to visit Cannabis Act legislative review for updated information on the legislative review.

References

- Footnote 1

-

On April 13, 2018, the Government of Canada introduced Bill C-46 in order to strengthen legislative provisions relating to driving while impaired by drugs, including cannabis. In March 2022, the Department of Justice released its study outlining early successes and ongoing challenges relating to the implementation of former Bill C-46, An Act to amend the Criminal Code (offences relating to conveyances) and to make consequential amendments to other Acts. For more information on this study, visit: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/csj-sjc/c46/index.html.

- Footnote 2

-

Rup. J., Goodman, S., & Hammond, D. (2020). Cannabis advertising, promotion and branding: Differences in consumer exposure between 'legal' and 'illegal' markets in Canada and the US. Preventive Medicine, 133.

- Footnote 3

-

Factsheet: Health Effects of Cannabis. (2017). Health Canada. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/campaigns/27-16-1808-Factsheet-Health-Effects-eng-web.pdf

- Footnote 4

-

Cannabis: What Parents/Guardians and Caregivers Need to Know. (September 2020). Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/cannabis-parent-infosheet-pdf.pdf

- Footnote 5

-

Cannabis: What Parents/Guardians and Caregivers Need to Know. (September 2020). Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/cannabis-parent-infosheet-pdf.pdf

- Footnote 6

-

Rup. J., Goodman, S., & Hammond, D. (2020). Cannabis advertising, promotion and branding: Differences in consumer exposure between 'legal' and 'illegal' markets in Canada and the US. Preventive Medicine,133.

- Footnote 7

-

Goodman, S., Leos-Toro, C., & Hammond, D. (2022). Do Mandatory Health Warning Labels on Consumer Products Increase Recall of the Health Risks of Cannabis? Substance Use & Misuse, 37(4), 569-580.

- Footnote 8

-

Canadian Cannabis Survey (CCS) cycles from 2018 to 2021.

- Footnote 9

-