Regulatory modernization of foods for special dietary use and infant foods: Divisions 24 and 25 of the Food and Drug Regulations

Consultation closed

This document is part of the consultation on the Regulatory modernization of foods for special dietary use and infant foods. The consultation ran from November 28, 2023 to February 26, 2024.

Table of contents

- List of abbreviations

- Executive summary

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Background

- 3.0 Description of proposed modernized framework

- 4.0 A division for foods for a special dietary purpose

- 5.0 A division for foods that are not foods for a special dietary purpose

- 6.0 Conclusion

- Appendix 1: Lexicon

- Appendix 2: Consultation questions

List of abbreviations

- AI

- Adequate Intakes

- CDRR

- Chronic Disease Risk Reduction Intake

- Codex

- Codex Alimentarius Commission

- CFIA

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency

- DRI

- Dietary Reference Intakes

- DV

- Daily value

- EU

- European Union

- FLD

- Formulated liquid diets

- FDR

- Food and Drug Regulations

- FNF

- Formulated nutritional foods

- FOP

- Front-of-package

- FMR

- Formulated meal replacements

- FSANZ

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand

- FSMP

- Food for special medical purposes

- FSDU

- Foods for special dietary use

- FSDP

- Food for a special dietary purpose

- FVLED

- Foods for a very low energy diet

- HMF

- Human milk fortifiers

- MR

- Meal replacements

- NASEM

- National Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine

- NFt

- Nutrition Facts table

- NIFI

- New infant formula ingredient

- NS

- Nutritional supplements

- PPHM

- Prepackaged human milk

- RDA

- Recommended Dietary Allowance

- TMAL

- Temporary Marketing Authorization Letter

- TDR

- Total diet replacement

- UL

- Tolerable Upper Intake Level

- WHO Code

- World Health Organization International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes

Executive summary

This pre-consultation paper presents the modernization proposal for Divisions 24 and 25 of the Food and Drug Regulations (FDR), which govern foods for special dietary use (FSDU) and foods for infants in Canada. The current regulations, developed decades ago, are outdated and inflexible, hindering the integration of scientific advancements and updates to recommended intakes. This rigidity poses challenges for industry innovation, limits availability of products approved in other countries and leaves Canada more vulnerable to shortages.

Regulatory modernization would continue to support the safety and nutritional adequacy of these foods, while also fostering increased innovation and alignment with international jurisdictions, when possible and within the Canadian regulatory context. It would create a more competitive marketplace and improve access to critical nutrition products for Canadians. This modernization aligns with the 2019 amendment to the Food and Drugs Act, introducing the term "food for a special dietary purpose" (FSDP) and supports the ongoing development of a regulatory framework for human clinical trials on these products.

The modernization initiative proposes a comprehensive restructuring of the regulatory requirements. One crucial aspect is the introduction of a clear differentiation between products that meet the definition of FSDP and those that do not. FSDP would be subject to enhanced regulatory oversight, including premarket authorization for most infant FSDP, and stop-sale provisions to protect public health. Moreover, compositional requirements both for products that are FSDP and those that are not would be updated to reflect the latest Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI) and be incorporated by reference, when feasible. The proposal also aims to improve product labelling by requiring detailed information on FSDP labels for safe use and differentiation from products that are not FSDP.

In conclusion, the proposed regulatory modernization for Divisions 24 and 25 aims to address current limitations and challenges in the regulation of FSDU and infant foods. By promoting flexibility, aligning with scientific advancements, and encouraging innovation, regulatory modernization will continue to ensure product safety while enhancing accessibility and diversity of products for the Canadian market. This diversity will help mitigate the risk of shortages to better support the health and well-being of all Canadians, particularly vulnerable groups relying on specialized nutrition products. Health Canada's commitment to modernization underscores its dedication to public health, ensuring that Canadians have access to high-quality, safe, and nutritious foods for their unique dietary needs.

1.0 Introduction

Divisions 24 and 25 of the Food and Drug Regulations (FDR) prescribe the requirements for foods for special dietary useReference 1 (FSDU) and foods for infants (individuals less than one year old). Division 24 sets out the requirements for foods for individuals over 1 year through a prescribed list of product categories that are permitted to be represented asReference 2 FSDU, including formulated liquid diets (FLD), meal replacements (MR), and nutritional supplements (NS). Division 25 regulates foods for infants such as infant formula, human milk fortifiers (HMF), and conventional infant foods like cereals and strained fruit.

While the regulations for FSDU and infant foods aim to ensure safety and nutritional adequacy, they are prescriptive and outdated. To comply with the regulations, FSDU must adhere to compositional requirements that have remained unchanged for decades, despite scientific advancements and updates to recommended intakes that have occurredReference 3.

The limitations of the current framework pose challenges for industry in introducing innovative products to the Canadian market. As a result, many products available in other countries are not permitted for sale in Canada, leaving the country with a less diversified supply that may be more affected by a shortage. This vulnerability was evident in 2022 when Canada experienced the impact of global shortages, particularly with infant formula and HMF, and dietary products for individuals with inherited metabolic disorders (commonly known as metabolic products).

To help address these shortages, Health Canada published an interim policy recommending that the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) exercise enforcement discretion on certain provisions of the FDR. This facilitated the importation of products manufactured to standards comparable to those in Canada. Whereas the interim policy helped provide short-term access to these products for vulnerable groups, lasting regulatory solutions are needed to reduce the likelihood of future shortages and mitigate the impact when they occur.

In 2019, the Food and Drugs Act was amended to introduce the term, "food for a special dietary purpose"Reference 4 (FSDP), supporting the development of a regulatory framework that would enable human clinical trials on these products. The term FSDP was specifically crafted to accurately scope comprehensive regulations for certain foods, such as infant formula, human milk fortifiers, and other medical foods, where stringent regulations are essential to prevent harm to health. Currently, FSDP that are non-compliant as well as FSDP with premarket requirements, such as new or majorly changed infant formula, that have not yet undergone premarket review by Health Canada are not permitted to be used in clinical trials. This modernization initiative aims to restructure the regulatory requirements in a manner that would complement the ongoing development of the FSDP clinical trial framework by differentiating FSDP from foods that do not meet the definition of an FSDP.

Since the current regulatory framework was developed, more flexible modern regulatory instruments have become available, including the incorporation by reference authority. This allows regulatory amendments, such as updates to compositional requirements, to be adopted administratively as soon as the scientific assessment and related consultations have been completed. Within the proposed modernized framework, compositional requirements, where prescribed, would reflect the latest Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI)Reference 5 and be published in an incorporated by reference document, when possible, to enable administrative amendments to the compositional requirements to align with new scientific evidence.

Recognizing the importance of clear and complete labelling to support the safe use of FSDP, revised labelling requirements are proposed for these products to provide more information on the product label, helping to ensure safe use and distinguishing them from lower-risk food products, like gluten-free foods. The labelling requirements for lower-risk food products, such as MR and NS would also be revised to better align with the general requirements for prepackaged foods, including the use of a Nutrition Facts table (NFt).

Overall, this regulatory modernization proposal aims to support increased innovation, improve alignment with international jurisdictions, and reduce barriers to importing these foods into Canada. The new regulatory framework would improve access to these critical nutrition products for Canadians as well as promote a diverse market to reduce the risk of shortages.

1.1 Purpose

The purpose of this pre-consultation document is to present Health Canada's proposal for modernizing the regulatory framework for FSDU and foods for infants in order to gather input from interested parties. Stakeholder comments in response to this proposal will inform the drafting of regulations, which will be pre-published in Canada Gazette Part I for public comment. Section 2.0 outlines the current Canadian regulatory landscape and its limitations, while also offering an international perspective on similar frameworks. Sections 3.0 to 5.0 provide details on the proposed modernized framework for stakeholder consideration, complemented by a set of guiding questions in Appendix 2: Consultation questions.

2.0 Background

2.1 Canadian context

2.1.1 A brief history of Division 24, Food and Drug Regulations

In 1974, Division 24 was added to the FDR, establishing the closed list of permitted FSDU products in B.24.003 that currently remains in effect. Initially, this list only included "dietetic" foods, such as carbohydrate-reduced, sugar-free, calorie-reduced, or low-sodium foods. However, in 1978, the closed list of FSDU categories was expanded to include FLD, foods represented for gluten-free diets, protein-restricted diets, and diets low in specific amino acids. This amendment also included the addition of the FSDU definition and the establishment of specific labelling and compositional requirements for each category of FSDU.

The latest major regulatory amendments to Division 24 occurred in 1995, when MR, NS, and foods for use in weight-reduction diets were added to the list of categories that can represent as FSDU. This amendment also repealed some of the older categories of FSDU that were introduced in 1974 and that no longer fit the scope of the FSDU framework (for example, carbohydrate-reduced foods, fat-modified foods, low fat foods, calorie-reduced foods, etc.).

Although the market has since evolved due to advances in science and innovation, the list of products that are permitted to be represented as FSDU and their requirements have remained unchanged since 1995. In 2005, regulatory amendments were proposed for MR, NS, and prepackaged meals for weight-reduction diets to amend the compositional requirements; however, this regulatory package did not proceed, and these regulatory amendments were never promulgated.

2.1.2 Issues with the current regulatory framework: Division 24, Food and Drug Regulations

Issues with the Canadian FSDU framework include its narrow scope, inflexible and outdated compositional and labelling requirements, and misalignment with regulatory frameworks internationally. These issues are outlined in more detail in this section.

a) Restricted access due to closed list of foods for special dietary use categories

Division 24 is characterized by a closed list of product categories that can be represented as FSDUReference 6. This list excludes several products that are available in other jurisdictions, including pre-and postoperative beverages to enhance recovery after surgery, metabolic products for inherited metabolic disorders unrelated to protein metabolism (for example, galactosemia), and other specially formulated foods that address the unique nutrient requirements of individuals with medical conditions. The narrow scope of the list hinders access to new and innovative products in Canada, making it difficult to meet consumer needs.

b) Outdated compositional requirements

The outdated and prescriptive compositional requirements mean that products with nutrient amounts that align with the latest recommendations of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), as well as those specifically formulated for individuals with unique nutrient needs due to medical conditions, do not comply with the FDR and cannot be sold in Canada without a Temporary Marketing Authorization Letter (TMAL). These outdated requirements do not align with standards in other jurisdictions, forcing manufacturers to develop separate formulations exclusively for the Canadian market or apply for a TMAL. Industry stakeholders have expressed difficulties in manufacturing products that comply with the narrow nutrient ranges stipulated in the FDR. Meeting the minimum requirements at the end of shelf-life without exceeding the regulatory maximum poses burdensome technical challenges.

c) Insufficient labelling requirements

Existing labelling requirements for some FSDU do not meet the needs of consumers and do not support informed decisions. For example, the nutrition labelling requirements for products intended for use by the general population lack consistency not only among product categories but also with other prepackaged foods. While most conventional prepackaged foods are required to carry an NFt and, in some cases a front-of-package (FOP) nutrition symbol, MR and NS are prohibited from carrying this information. Not having access to information provided in an NFt makes it difficult for consumers to make healthier and more informed food choices, including for people that require certain information to manage their health conditions. For example, MR and NS are not required to declare sugars content on the label, and manufacturers often choose not to disclose this information. This makes it challenging for diabetic individuals to make appropriate decisions. Consequently, concerned consumers have contacted Health Canada, expressing their desire to know the sugars content of these foods.

Furthermore, labelling requirements for FSDU are very different from those in other jurisdictions. This adds unnecessary burden and may discourage companies from distributing their products in Canada, potentially limiting access to essential products for vulnerable Canadians.

d) Outdated advertising restrictions

Parts B and D of the FDR prescribe advertising restrictions for certain FSDU namely FLD, foods for a very low energy diet (FVLED), fortified foods for protein-restricted and low amino acid diets, and fortified foods for gluten-free diets. According to Section 2 of the Food and Drugs Act, any communication aimed at promoting the sale of a food is considered an advertisement. This means that any means of promotion falls under advertising and would thus be restricted for these categories of FSDU.

The purpose of these advertising restrictions was to help ensure that consumers consult their health care providers before using these products. However, these restrictions are no longer suitable in today's era, where many individuals actively participate in their health care decisions. Additionally, advertising restrictions have become impractical in the current context of online advertising and distribution. With these restrictions, manufacturers and distributors are unable to advertise these products using social media; including providing links to online marketplaces or information on how to purchase these products. As such, consumers searching online for products appropriate for their needs are not aware that these types of FSDU are available for purchase. This, in turn, makes it difficult to access a wide range of products, particularly for individuals living in remote communities with limited access to retail locations.

e) Outdated requirements for foods represented for use in weight reduction diets

Division 24 restricts the representation of foods intended for use in weight reduction diets to FVLED, MR, prepackaged meals, and foods sold by a weight reduction clinic. The intent of this restriction was to help ensure that only those products that control food intake while maintaining nutrient adequacy can be represented as suitable options for weight reduction diets. Consequently, these foods are subject to additional regulatory requirements, which are out of date.

FVLED are intended for use under medical supervision and have detailed compositional requirements that are based on outdated recommended intakes. Premarket notification is required prior to the sale of these foods, yet to date, Health Canada has not received any notifications, suggesting that the requirements for this category are not aligned with what is available on the market.

Similarly, MR for use in weight reduction diets, as well as prepackaged meals and food sold in a weight reduction clinic are required to include a sample seven-day menu that meets certain requirements based on the 1992 version of Canada's Food Guide to Healthy Eating. These foods and the accompanying sample menu must adhere to compositional requirements that are based on outdated recommended intakes.

2.1.3 A brief history of Division 25, Food and Drug Regulations

In 1976, Division 25 was added to the FDR, establishing requirements for infant foods, including infant formula. It introduced sodium restrictions to infant foods and set compositional requirements for infant formula, both of which have remained unchanged since their promulgation.

Significant amendments were made to Division 25 in 1983, including the addition of provisions enabling the Department to order the stop-sale of a potentially inadequate or unsafe infant formula. Additionally, the term human milk substitute was introduced to harmonize with international terminology, reserving the term infant formula for use as the common name for human milk substitutes. Division 25 was also expanded to include any product sold or represented as a substitute for human milk, any product represented for use as an ingredient of a human milk substitute and foods containing a human milk substitute.

The most recent major amendments to the infant formula regulations occurred in 1990 when premarket notification requirements were introduced for new and majorly changed human milk substitutes. Fast forward to 2021, Division 25 underwent further significant amendments to include the addition of provisions for HMF. Prior to this regulatory amendment, HMF were not permitted to be sold in Canada; however some HMF were temporarily made available following a thorough safety assessment by Health Canada.

2.1.4 Issues with the current regulatory framework: Division 25, Food and Drug Regulations

a) Infant food nomenclature and definition issues

The FDR broadly defines infant food as food that is labelled or advertised for consumption by infantsReference 7. The definition is inclusive of all infant foods, including infant formula, HMF, and conventional foods for infants aged 6 months or more such as infant cereals and strained fruit.

In the case of infant formula, the regulatory term prescribed is "human milk substitute". However, the regulations also require the use of the common name "infant formula" on product labels and in advertising. This dual naming is overly complicated and unnecessary. Additionally, the definition for "human milk substitute" includes foods represented for use as ingredients in human milk substitutes, but such ingredients do not seem to be marketed in Canada. The only ingredients permitted to be required for addition in the directions for use of infant formula are water and/or a source of carbohydrate.

Overall, the regulations concerning infant foods would benefit from clearer and more consistent terminology and definitions to avoid misunderstandings and ensure that the regulatory framework aligns with the intended purpose and categorization of infant foods.

b) Regulatory gap for certain infant foods

Due to the outdated nature of the existing regulatory framework for infant foods, there are a number of globally available infant foods that are not addressed in Division 25 of the FDR.

- Specialized infant formula

Infant formula must be formulated to meet specific compositional requirements. While some exemptions to these compositional requirements exist, they are limited to specific cases, such as infant formula represented for diets that are fat-modified, low amino acid, low mineral, low vitamin D, or any combination of these. These exemptions are narrow in scope and could pose barriers to accessing specialized infant formula that may be beneficial or even necessary to infants with specific medical needs. For example, the current regulations do not allow for modifications to preterm formulas needed in specific circumstances (for example, low birth weight, extremely low birth weight, etc.). Removing the unnecessary barriers would make approving new and innovative products less complicated and more streamlined.

- Prepackaged human milk

Prepackaged human milk (PPHM) from Canadian milk banks is carefully screened, processed, and packaged to ensure safety, and is currently used in hospital settings. It serves as a supplement when a mother's milk is insufficient or unavailable. Currently, most PPHM in Canada is sourced from four not-for-profit human milk banks operating in Calgary, Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver. Health Canada is also aware of commercial human milk processing companies selling their products in other countries.

There are no specific provisions for PPHM in Division 25. Instead, PPHM is subject to the general requirements for conventional prepackaged foods outlined in the Food and Drugs Act and Regulations. The absence of specific regulatory requirements, including provisions related to safety and quality, as well as tailored labelling information for the safe use of these products, is concerning for this category of food intended for a vulnerable subpopulation.

- Other infant foods

The existing regulations do not account for some other types of infant foods, including infant medical foods that are not intended to replace infant formula and supplemental components that do not meet the definition of an HMF, such as single macronutrient 'modular' type products that may be mixed with other products before use (for example, protein, carbohydrate, or fat modulars). The lack of regulatory provisions for these products further limits the options available to infants with unique dietary requirements.

c) Misalignment with the World Health Organization International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes

The World Health Organization established the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk SubstitutesReference 8 (WHO Code) in response to the global decline in breastfeeding, influenced by sociocultural factors and the promotion of infant formula. Adopted by the World Health Assembly in 1981, and updated in 2017, the WHO Code aims to ensure the provision of safe and adequate nutrition for infants by protecting and promoting breastfeeding, while regulating the appropriate use of human milk substitutesReference 9, when necessary, through responsible marketing and distribution practices.

As a signatory of the WHO Code, Canada has an obligation to support and promote breastfeeding, facilitate breastfeeding by mothers through legislative and social action, and prevent inappropriate sales promotion of infant foods that can be used to replace human milk. However, the FDR does not reflect the recommendations outlined in the WHO Code, particularly regarding the restriction of advertising or other forms of promotion, as well as the requirement to label human milk substitutes to provide the necessary information on the appropriate use of the product to not discourage breastfeeding.

d) Outdated compositional requirements

The existing compositional requirements for infant formula have not been amended since their introduction into the regulations in 1976, despite advances in nutrition science and updates to recommended intakes. Similarly, the fortification provisionsReference 10 for infant cereal products, a conventional infant food, have not been amended since their introduction in the FDR in the 1960s. These provisions are not based on current nutrient recommendations for infants and do not include maximum levels for mineral nutrients despite the vulnerability of this subpopulation.

Additionally, the regulations for conventional infant foods establish sodium limits for a closed list of product categories and the amounts vary by product type. The rationale for differentiating sodium limits according to product type is unclear and the closed list fails to encompass all categories of conventional infant food available on the market.

e) Problematic premarket notification

Based on the current regulations, regulated parties must notify Health Canada at least 90 days before selling or advertising a new infant formula. However, the review of a premarket notification submission for a new infant formula or major changes to an existing infant formula generally takes longer than 90 days. This extended duration includes pauses in the review process to accommodate the submission of additional information by manufacturers. While regulated parties usually wait until Health Canada completes its review, there is no stipulation in the current regulations that prevents the sale of an infant formula before the review is completed, thus introducing a potential risk to the health and safety of infants. While the existing stop-sales provisions enable the Minister to halt the sale of products currently on the market, it is a reactionary measure.

f) Voluntary separate review of new infant formula ingredients

New ingredients that have not been previously used in an infant formula need to undergo a novelty determination. If the ingredient is determined to be novel, then information to support a novel food review is required. If the ingredient is determined not to be novel, a voluntary new infant formula ingredient (NIFI) assessment is conducted by Health Canada to determine its safe use for infants. However, the absence of regulatory requirements related to NIFI submissions means that there is no legal obligation to obtain a separate authorization for a NIFI before incorporating it into an infant formula premarket notification submission. Evaluating the NIFI during the assessment of an infant formula introduces complexity that could have been resolved before the infant formula submission and extends the review timeline. Therefore, clarifying the requirements and process for NIFI would help streamline the review. This would include clarifying questions related to data ownership and proprietary information between the infant formula manufacturer and the NIFI manufacturer.

2.1.5 Temporary measures to address an outdated regulatory framework

Throughout the years, Health Canada has implemented temporary measures to address challenges related to the outdated regulatory framework. One such measure was interim marketing authorizations, which were used as a mechanism to bridge the time between the completion of the scientific evaluation of certain enabling amendments and publication of the approved amendments in the Canada Gazette, Part II. Although this regulatory tool is no longer available under the FDR and interim marketing authorizations have expired, the changes that were enabled continue to be needed to address important public health needs. For instance, interim marketing authorizations were issued to increase the maximum levels of micronutrients in term and preterm infant formula as well as FLD, and to exempt FLD from the compositional requirements when formulated specifically for patients with renal failure.

TMALs are another regulatory tool under the FDR that have been used by Health Canada to authorize the sale of certain FSDU. A TMAL authorizes the temporary sale of a non-compliant product in Canada so that real world marketing research can be conducted in order to inform a regulatory amendment. Over the past decade, hundreds of TMALs for FSDU have been issued by the Department in order to inform this regulatory modernization initiative for FSDU. This includes TMALs issued for MR and NS to facilitate the safe transition of these products from the natural health products framework to the food regulatory framework. TMALs have also been issued for FSDU intended for children, whose revised nutrient needs are not reflected in the current compositional requirements.

Health Canada also periodically issues interim policy statements as a temporary measure to signal its intention that certain products that do not comply with the FDR remain available until regulatory amendments can be made. Health Canada has recently published two interim policy statements to address outdated regulatory requirements for prepackaged human milk (PPHM) and metabolic products. These policy statements signaled the Department's commitment to modernize the regulations for these types of products. Accordingly, proposals for PPHM and metabolic products have been included as part of this modernization initiative. Once final regulatory amendments are implemented, the interim policies for these types of products will no longer be in effect.

Temporary measures such as TMALs are inefficient, time-consuming and impose substantial administrative burden on both industry and Health Canada. Industry stakeholders have expressed that the often lengthy process required to obtain approvals can cause delays in getting products to market. Moreover, interim policy statements that rely on enforcement discretion lack regulatory certainty and transparency for industry and can create the appearance of an unequal playing field for industry.

2.1.6 Shortages of foods for a special dietary purpose

A shortage can arise from a range of circumstances, including manufacturing disruptions, difficulties in accessing raw materials, stockpiling, surges in demand, and unforeseen events affecting the global supply chain. In recent years, shortages of FSDP have become a significant concern due to global supply chain issues and product recalls.

Canada is particularly susceptible to shortages of FSDP due to its small market size and its reliance on a limited number of suppliers. Compounding this vulnerability is the outdated regulatory framework which poses unnecessary restrictions on the importation of FSDP available in other countries with similar safety standards.

Since early 2022, Canada has experienced shortages of FSDP, including infant formula, HMF, and metabolic products. These shortages were attributed to the recall of several powdered infant formula and the subsequent temporary closure of a major manufacturing facility in the United States (US), which globally supplies a significant portion of these products. This recall and production halt further exacerbated the strain on a supply chain challenged by the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

To help mitigate these shortages, Health Canada published an interim policy recommending that the CFIA temporarily exercise enforcement discretion for the importation of certain non-compliant products from other countries that adhere to high-quality manufacturing standards comparable to those upheld in Canada.

Shortages of FSDP can have serious consequences. These products serve as a critical source of energy and essential nutrients for vulnerable Canadians. Shortages can also lead to inflated prices for the limited supply available. Furthermore, these shortages place a heavy burden on the healthcare system, requiring health care providers to invest valuable resources and time in finding suitable alternative products. This can result in delayed or restricted access to FSDP, which can lead to adverse health outcomes.

The recent shortages of infant formulas and other FSDP have underscored the need for a more diverse and resilient supply for these products, and that updated regulations could contribute to this outcome. While interim measures were helpful in the short-term, lasting regulatory solutions are needed. Introducing regulatory amendments solely related to shortages would provide mechanisms to better address shortages when they occur, but these would not effectively minimize the risk of future occurrences. Modernizing the existing regulatory framework therefore requires a comprehensive approach that also addresses some of the underlying regulatory barriers that contribute to the risk of shortages. For example, this would include updating the outdated compositional requirements for certain FSDP.

2.2 Stakeholder engagement & market data

Over the years, consumers, health professionals, and industry stakeholders have consistently urged Health Canada to address the challenges associated with the outdated regulatory framework for FSDU and foods for infants. Feedback provided in response to multi-stakeholder consultations, a call for FSDU data as well as input obtained from external scientific articles and publications has been used to develop the proposed modernized regulatory framework described herein.

2.2.1 Foods for special dietary use

In 2017, the University of Toronto Program in Food Safety, Nutrition and Regulatory Affairs and the Canadian Nutrition Society co-hosted a multi-stakeholder workshop of experts, including health professionals, researchers, officials from Health Canada and industry stakeholders, to discuss issues with the Division 24 framework. This workshop, entitled "How to Optimize Foods for Special Dietary Use in Canada – Nutritional Requirements, Innovation, and Regulation"Reference 11, considered the context of global regulations, the importance of FSDU to nutrition and health, as well as next steps for addressing challenges and opportunities for regulating and using FSDU. There was consensus among workshop participants that the current Division 24 regulations do not best utilize current nutrition recommendations and food science/technology research, allow for innovation, meet the needs of users in clinical and nonclinical settings, nor support access to preferred products. The workshop resulted in the recommendation to develop a regulatory framework for FSDU in Canada that is modern, safe, flexible, innovative, and health driven.

In 2019, Health Canada requested data from manufacturers and distributors about FSDU that were sold in Canada, products that were planned for sale in Canada in the foreseeable future, as well as products that were sold in other jurisdictions but could not be sold in Canada under the current regulations. Information on about 100 products was provided by five respondents, including details on the intended use of the product, information on sales to date as well as projected, and product labels.

Respondents were also invited to communicate the challenges they encountered with the current FSDU regulations. A number of regulatory irritants were identified, including the closed list of product categories permitted to be represented as FSDU, outdated compositional requirements, issues with the current labelling requirements and lack of harmonization with respect to compositional requirements between Canada and main trading partners. These issues create barriers to the distribution of FSDU in Canada by preventing the use of global formulations and labels and therefore prevents access to innovative FSDU by Canadians.

In addition, an article published in 2019Reference 12 by the Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society highlights opportunities for the Canadian government to modernize its regulations for medical nutrition products and harmonize with international jurisdictions. The article underlines the challenges faced by patients in accessing these products due to the gaps in the current regulatory framework. The author suggests that, based on precedents from international regulatory systems for these products, the key to modernizing the Canadian framework will be to address the regulations' inherent limitations in flexibility, adaptability, and capacity to interface congruently with other regulatory systems.

2.2.2 Infant formula

In March 2017, an industry association submitted a discussion document to Health Canada regarding various aspects of the Department's guidance documents for infant formula. Their feedback included recommendations on topics such as the information required for establishing a new manufacturing facility, infant formula premarket notification, and the guide to industry on the scientific evidence needed to establish nutritional adequacy of infant formula. The association also expressed concerns about the current timeframes for premarket notification requirements, emphasizing the importance of sufficient scheduling and planning to effectively bring products to market.

In May 2018, Health Canada met with the industry association and committed to reviewing the feasibility of collaborating with international jurisdictions that share similar manufacturing standards to alleviate unnecessary burdens on the industry.

In June 2022, the industry association brought their ongoing concerns to the Treasury Board of Canada, as part of the Government of Canada's Let's Talk Federal Regulations initiative, specifically within the Breaking Down Inter-jurisdictional Barriers online consultation project. The association's primary concern revolved around Canada's regulatory misalignment with major international trading partners. They strongly urged the Department to implement risk-based processes for infant formula that undergo simple, low-risk changes. This would enable a faster review through an expedited process, ultimately facilitating smoother market entry for such products.

2.2.3 Shortages of foods for a special dietary purpose

In February 2023, Health Canada conducted a survey of key stakeholders involved in the Department's response to the shortages of certain FSDP for infants and children. The objective was to gather comprehensive feedback regarding the Department's management of the shortages and the effectiveness of the interim policy implemented to mitigate them. Stakeholders emphasized the importance of developing a comprehensive action plan to effectively manage potential future FSDP shortages. They highlighted the necessity of establishing regulations to ensure a consistent and reliable supply of infant formula and other FSDP in Canada. Furthermore, stakeholders proposed the development of a regulatory framework, similar to the one used for managing drug shortages, to help address and mitigate potential issues related to FSDP shortages in the future.

The survey and subsequent feedback provided valuable insights for Health Canada in assessing the effectiveness of their management of the FSDP shortages. The recommendations and concerns raised by stakeholders will inform ongoing efforts to enhance policies, regulations, and communication strategies to better address and mitigate such shortages in the future.

2.3 International context

Health Canada conducted a comprehensive review of comparable existing regulatory frameworks internationally. Similar to the Department's proposed approach, other frameworks make a clear distinction between "special dietary products" intended for more vulnerable populations (specifically FSDP) and those intended for self-selection by the general population. While the range of products recognized as "special dietary" varies, many jurisdictions have established separate and specific requirements for these products, in order to reflect their intended purpose and use by vulnerable populations.

Over the past decade, several jurisdictions, including the European Union (EU), and Australia and New Zealand, have embarked on regulatory modernization initiatives for FSDP. Health Canada has an opportunity to address deficiencies in the existing regulatory framework by leveraging similar updates and flexibilities already being implemented in those regions.

The proposed approach for modernization of Divisions 24 and 25 draws upon the principles and best practices established by these other frameworks while ensuring that it considers specific Canadian needs and regulatory context.

2.3.1 Codex Alimentarius Commission

The Codex Alimentarius Commission (Codex) is an international organization established by the Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization. Its purpose is to develop international food standards, guidelines, and codes of practice. These standards and guidelines are intended to help ensure that food meets specific nutrient composition, labelling and claims requirements, thereby facilitating international trade and maintaining consistent quality and safety across borders.

To ensure alignment, where possible, with international regulations and promote consistent quality and safety of special dietary foods, Health Canada considered various relevant Codex standards and guidelinesReference 13. These texts provide recommendations for the labelling and composition of food including infant formula, infant food, food for special medical purposes (FSMP) (which encompasses some categories of products considered FSDU in Canada as well as other types of medical foods not covered under Canada's current framework), and food for persons intolerant to gluten.

2.3.2 European Union

In 2013, the EU replaced their framework for foods for particular nutritional uses, with the introduction of foods for specific groups in order to strengthen provisions on foods for vulnerable populations that require protection and to ensure clear categorization, harmonization, and free movement of these foods across the EUReference 14. This change was driven by the need to enhance consumer protection concerning the content and marketing of these products, streamlining a complex and fragmented system that had evolved over three decades. This framework establishes requirements for the labelling and composition of infant formula, processed cereal-based food and other baby food, FSMP, and total diet replacement (TDR) for weight control.

Some foods are excluded from this framework as they were deemed sufficiently covered under horizontal legislation (for example, general food legislation on nutrition and health claimsReference 15 and the addition of vitamins and minerals and of certain other substances to foodsReference 16). Foods excluded from the framework include toddler milks and similar products intended for young children, foods intended for sportspeople, other fortified foods formulated for nutritionally vulnerable individuals such as those intended to replace a meal or to supplement the diet, and gluten-free/very low gluten foods and lactose-free foods.

2.3.3 Australia and New Zealand

Part 2.9 of the Food Standards CodeReference 17 of Australia and New Zealand establishes compositional and labelling requirements for special purpose foods, which are food products intended for physiologically vulnerable individuals and population subgroups. This includes infants, young children, pregnant and lactating women, and people with certain medical conditions or special dietary requirements. Special purpose foods include various products such as infant formula, food for infants, FSMP, formulated meal replacements, formulated supplementary foods, and formulated supplementary sports foods. While formulated meal replacements, supplementary foods and sports foods are intended for the general population, they are included in the framework because individuals who consume these products have unique dietary needs which may vary from dietary recommendations for the general population.

The regulatory modernization efforts in Australia and New Zealand are still ongoing, with a particular focus on infant formula products, including those intended for medical purposes. Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) has been actively consulting on proposals to amend these regulations since 2011. The objective of these proposals is to bring clarity to the regulatory landscape, incorporate the latest scientific evidence, and align the regulations with international standards wherever possible.

2.3.4 United States

Unlike Canada and many other international jurisdictions, the United States does not have a distinct regulatory framework for special dietary foods. Although there is a framework for FSDUReference 18, it is rarely used, as most products shifted to being classified as medical foods in the 1990sReference 19. The definition of medical foods in the United States is limited to products intended to meet the distinct nutritional requirements of a specific disease or condition, used under medical supervision, and designed for the specific dietary management of that disease or condition.

There is a separate regulatory framework for infant formula in the United States, in which compositional and labelling requirements are prescribed. In early 2023, the United States Food and Drug Administration announced that a study will be conducted by NASEM to examine the challenges in regulating infant formula effectively. The study will contribute to the development of a long-term national strategy for better oversight and consumer protection.

3.0 Description of proposed modernized framework

3.1 Objectives

The objective of regulatory modernization is to establish a comprehensive framework encompassing products currently regulated under Divisions 24 and 25 of the FDR. To address the limitations of the current regulatory framework, Health Canada is proposing a modernized risk-based approach that is better aligned with international jurisdictions. The proposal stems from an extensive evaluation of Divisions 24 and 25 to identify outdated provisions and barriers to access critical nutrition products.

3.2 Restructuring Divisions 24 and 25 of the Food and Drug Regulations

The proposed modernization initiative would restructure Divisions 24 and 25 of the FDR, which currently differentiate products based on the age of intended consumers. The aim of restructuring is to redefine product categories and establish requirements based on the risk profile of the product and the vulnerability of the intended subpopulation. The proposed approach of one division for FSDP and another for products that are not FSDP would simplify the regulatory framework and establish clearer compositional and labelling requirements for all products commensurate with risk.

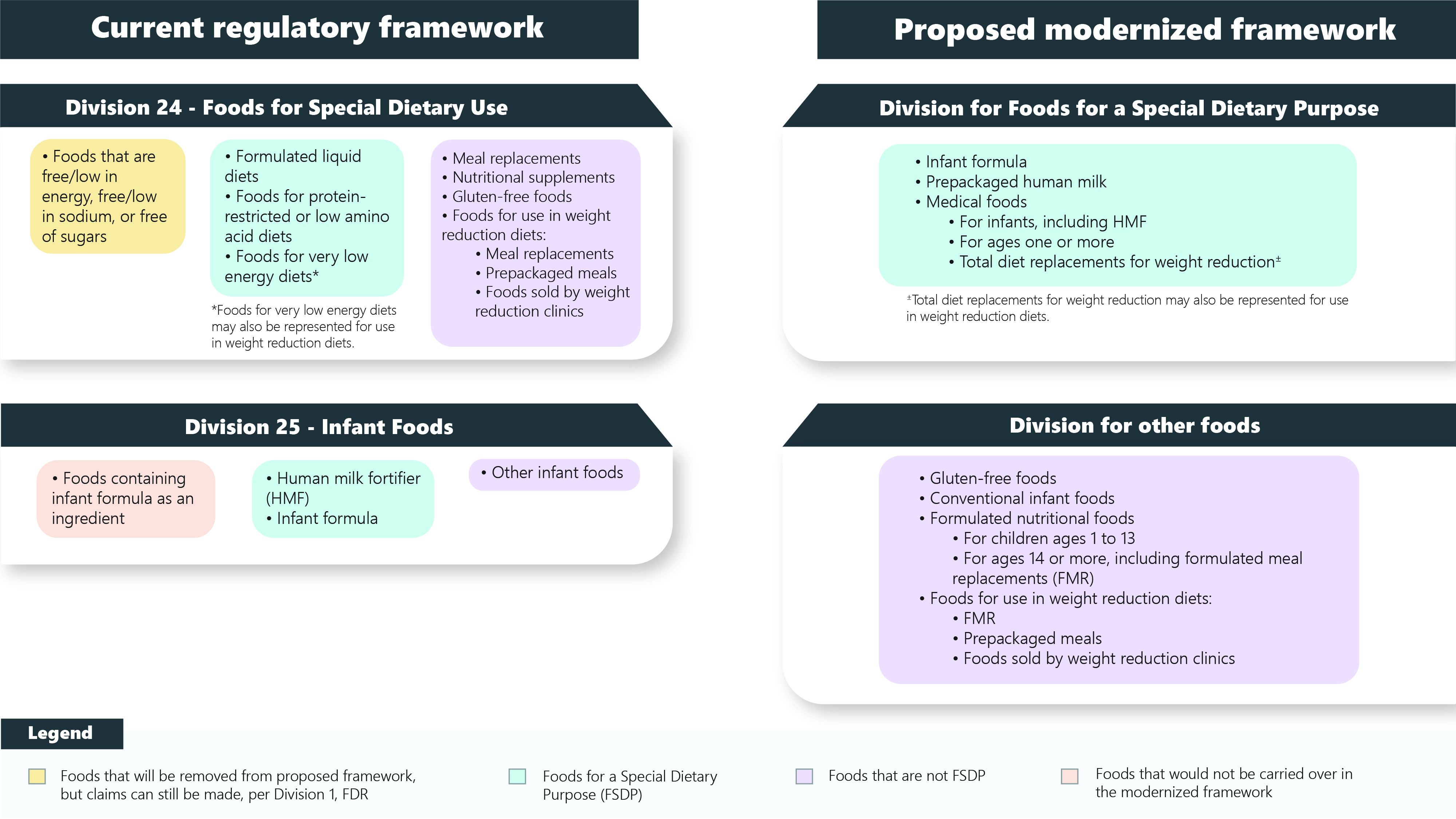

Figure 1 - Text description

Shown here is a figure that represents the current regulatory framework of Divisions 24 and 25 of the Food and Drug Regulations (FDR), and the proposed modernized framework.

The current regulatory framework for Division 24 of the FDR, foods for special dietary use (FSDU), includes three food categories. The first category includes foods that are free/low in energy, free/low in sodium, or free of sugars. These foods would be removed from the proposed framework, but claims would still be able to be made, per Division 1 of the FDR. The second category includes formulated liquid diets, foods for protein-restricted or low amino acid diets and foods for very low energy diets*. These foods would be captured in the proposed framework for foods for a special dietary purpose (FSDP). The third category includes meal replacements, nutritional supplements, gluten-free foods, and foods for use in weight reduction diets such as meal replacements, prepackaged meals and foods sold by weight reduction clinics. These foods would be moved to a division of the FDR that is separate from FSDP.

The current regulatory framework for Division 25 of the FDR, infant foods, includes three categories. The first category includes foods containing infant formula as an ingredient. and these foods would not be carried over into the modernized framework. The second category includes human milk fortifier and infant formula.

These foods would be captured in the proposed framework for FSDP. The third category includes all other infant foods. These foods would be moved to a division of the FDR that is separate from FSDP.

The proposed modernized framework includes a division for FSDP and a division for other foods. The food categories included in the proposed FSDP division are: infant formula, prepackaged human milk, medical foods for infants (including HMF), medical foods for ages one or more, and total diet replacements for weight reduction±.

The food categories in the proposed division for other foods are: gluten-free foods, conventional infant foods, formulated nutritional foods (for children ages 1 to 13 and for ages 14 or more, including formulated meal replacements), and foods for use in weight reduction diets (formulated meal replacements, prepackaged meals and foods sold by weight reduction clinics).

*Foods for very low energy diets may also be represented for use in weight reduction diets.

±Total diet replacements for weight reduction may also be represented for use in weight reduction diets.

To support access to safe products and provide a new pathway to manage future shortages, the regulations would provide a mechanism for exceptional importation in the case of shortages. As part of these provisions, companies would be required to report shortages of FSDP. The obsolete term ""FSDU" would be eliminated due to its redundancy and overlap with the term "FSDP". In addition, the term "medical foods" currently used in the United States would be adopted to refer to products intended for the dietary management of medical conditions and used under medical supervision.

The proposed division for FSDP would encompass higher-risk products intended for vulnerable subpopulations and require enhanced regulatory oversight. This includes infant formula, PPHM, and medical foods. This division would prescribe labelling requirements that differ from those of prepackaged foods for the general population. In most cases, premarket authorization would be required for FSDP intended for infants.

Products currently regulated under Divisions 24 and 25 that do not fall under the FSDP category would be placed in a separate division. This includes conventional infant foods, gluten-free foods, formulated nutritional foods, prepackaged meals and foods sold by a weight reduction clinic. These products are intended for self-selection by consumers and are not intended for use as a sole or primary source of nutrition under medical supervision. The regulatory requirements for these products would be updated to align with current nutrient recommendations and address consumer demand for nutrition information that is consistent with that on other prepackaged foods for the general population. Most of the nutrition labelling requirements unique to these foods would be removed, and these products would be required to carry an NFt and be subject to applicable FOP nutrition labelling requirements.

While the approach to modernizing the regulatory framework for products regulated under Divisions 24 and 25 is outlined in the following sections, some details, such as specific compositional requirements, will be available for stakeholder feedback during prepublication in Canada Gazette I.

To facilitate amendments in the future, the Department aims to incorporate by reference the compositional requirements for these foods, where appropriate. This approach would contribute to the creation of an agile regulatory framework, whereby compositional requirements can be amended administratively to align with the most up to date DRI and advancements in the field of nutrition science, ensuring that the framework remains responsive and in line with the evolving understanding of nutritional needs.

3.2.1 Product category exclusions from the revised framework

It is proposed to remove certain categories of foods from the regulatory framework. First, the framework would exclude foods on the sole basis of that they carry any of the following statements and claims set out in column 1 of the Table of Permitted Nutrient Content Statements and Claims: "free of energy", "low in energy", "free of sodium or salt", "low in sodium or salt" or "free of sugars". Although these foods are currently permitted to be represented as FSDUReference 20, Division 24 does not establish specific requirements for them.

Second, the framework would exclude foods containing infant formula. As these foods do not appear to be, nor are they expected to be on the market, they do not need to be retained in the modernized regulatory framework.

3.2.2 Transitioning from foods for special dietary use to foods for a special dietary purpose

The definitions for FSDU and FSDP both refer to foods that have been specially processed or formulated to meet the particular requirements of a person in whom a physical or physiological condition exists as a result of a disease or disorder (for example, medical foods such as FLDs, metabolic products, etc.). However, there are unique elements to both definitions as well, and are presented in Figure 2. FSDU includes foods for whom a particular effect, including but not limited to weight loss, is to be obtained by their controlled intake (such as MR for weight loss) while FSDP includes foods to be consumed as the sole or primary source of nutrition for an individual (such as infant formula).

Figure 2 - Text description

Shown here is a Venn diagram (two overlapping circles) that indicates the differences and similarities between the definitions of Foods for Special Dietary Use (FSDU) in B.24.001 for the Food and Drug Regulations and Foods for a Special Dietary Purpose (FSDP) in section 2 of the Food and Drugs Act. As indicated in the overlapping part of the circles, the definition of FSDU and the definition of FSDP both refer to foods that meet the requirements of a person in whom a physical or physiological condition exists due to an abnormal state for example, foods for protein-restricted diets).

There are unique elements to both the FSDU and FSDP definitions. FSDU include foods that impart a particular effect through controlled intake (for example, meal replacements for weight reduction), while FSDP includes foods to be consumed as the only or main source of nutrition (for example, infant formula for healthy term infants).

The modernized framework proposes removing the term FSDU and including a framework to regulate FSDP. This proposal would align with the addition, in 2019, of the term FSDP to the Food and Drugs Act and would eliminate confusion regarding these overlapping terms. By transitioning from FSDU to FSDP, the scope of products within this framework would be redefined, in particular, the framework would include products that are intended for use as a sole or primary source of nutrition for healthy individuals (for example, infant formula).

3.2.3 Clarifying current regulatory terms

Clarity on the term "infant foods" is required as the current nomenclature and definition create confusion. It is therefore proposed to revise the regulatory definition for infant foodReference 21 to address the issues with the current definition which has two uses in the regulations, by capturing all products intended for infants, including infant formula and other infant FSDP while also capturing conventional foods intended for infants. The proposed definition follows. Note that a new definition would be added to the regulations for conventional infant foods, which is proposed in subsection 5.1 Conventional infant foods.

a) Revised definition

The proposed revised definition for infant food would be:

infant food means a food that is labelled or advertised for consumption by infants including conventional infant foods and foods for a special dietary purpose

Note that certain regulatory requirements for infant foods would remain applicable to both conventional foods and infant FSDP. This includes the food additive provisionsReference 22 that are currently included in Division 25 of the FDR.

4.0 A division for foods for a special dietary purpose

The proposed modernization initiative includes establishing a division that would encompass products currently regulated under Divisions 24 and 25 of the FDR that meet the definition of an FSDP. Additionally, this division would cover FSDP that do not currently have specific provisions within the FDR.

This division for FSDP would include products that are currently regulated as FSDU, such as FLD, FVLED, and foods represented for protein-restricted and low amino acid diets (protein-related metabolic products). It would also encompass products that are not covered by the existing FSDU framework such as foods for dysphagia, fortified beverages for pre- and postoperative recovery, and metabolic products for disorders unrelated to protein metabolism, such as galactosemia and dyslipidemia.

With respect to foods for infants, the division for FSDP would include all infant formula, such as those intended for healthy infants and those for infants with diseases, disorders, or abnormal physical states (medical conditions), as well as PPHM, and medical foods for infants. Medical foods for infants are not intended to replace infant formula or human milk and are strictly intended for partial feeding. Examples include HMF, for which provisions were added to the FDR in 2021 and do not require any significant amendments to fit within the proposed framework. Additionally, single macronutrient type products that may be mixed with other products before use (such as protein, carbohydrate, or fat modulars) and other supplemental products (for example, feed thickeners) that can be added to infant formulas would be included within the division for FSDP.

The following categories of FSDP are proposed for this division, with details on each category outlined in the sections that follow:

- Infant formula

- Prepackaged human milk

- Medical food:

- Medical food for infants, including HMF

- Medical food for ages one or more

- Total diet replacement for weight reduction

4.1 Infant formula

This proposed category would include infant formula meeting the standard compositional requirements (such as infant formula intended for healthy term infants) as well as infant formula deviating from the standard compositional requirements (for example, infant formula intended for use under medical supervision such as metabolic infant formula for inherited metabolic disorders).

4.1.1 Definition

The following definition is proposed for infant formula:

infant formula means any food that is labelled or advertised for use as a partial or total replacement for human milk and is intended for consumption by infants

The proposed definition replaces the term "human milk substitute" in the existing definitionReference 23 with "infant formula" to match the common name. In addition, the proposed definition no longer refers to foods that are for use as an ingredient in a human milk substitute.

Water and/or a source of carbohydrate are the only substances that are currently permitted to be required for addition to infant formula in the directions for use. However, as it is no longer recommended to add a source of carbohydrate to infant formula other than under medical supervision, it is proposed to only allow the mention of water in the directions for use.

4.1.2 Compositional requirements

This proposed category of infant formula would include the following subcategories:

- Infant formula that meet the standard compositional requirements, such as infant formula for healthy term infants, lactose-free infant formula, and extensively and partially hydrolyzed infant formula

- Infant formula that deviate from the standard compositional requirements to meet the needs of infants with medical conditions. This could include preterm infant formula, metabolic infant formula for inherited metabolic disorders, and infant formula for catch-up growth

To ensure the nutritional requirements of infants with particular conditions are met, the proposed framework allows flexibility for the composition of infant formula to deviate from the standard requirements when medically justified. During the premarket authorization process, Health Canada would carefully evaluate the rationale and proposed deviations from the compositional requirements to assess their suitability for the target population.

The compositional requirements for infant formula will be updated to integrate the latest scientific evidence and align with international jurisdictions. To ensure transparency and gather valuable feedback, the draft compositional requirements for infant formula will be presented in a future consultation process.

a) New infant formula ingredients (NIFI)

To address the challenges associated with NIFI, a clear regulatory framework would be established, in which premarket authorization of a NIFI would be required prior to the submission of an infant formula containing the NIFI. By separating the NIFI review from the infant formula submission process, the timeline for reviewing an infant formula submission can be improved since the NIFI would have already received approval from Health Canada.

The premarket authorization requirements for NIFI would establish that the responsibility for preparing and submitting the necessary documentation lies with the NIFI manufacturer, rather than the infant formula manufacturer. If the ingredient in question was found to be safe for use in infant formula, then the infant formula manufacturer would be able to proceed with an infant formula submission for a product that contains the approved ingredient. This approach recognizes that the infant formula manufacturer may not have access to the proprietary information from the NIFI manufacturer, ensuring a more efficient and effective review process.

The following definition is proposed for NIFI:

new infant formula ingredient (NIFI) means a substance:

- that is intended for use as a food ingredient in infant formula, and

- that is not added to meet the compositional requirements for infant formula, and

- that is not a food additive or a novel food, and

- for which a history of safe use in infant formula has not been demonstrated in Canada

Furthermore, it is proposed to create a list of infant formula ingredients that have been authorized by Health Canada, which would be publicly accessible on the Government of Canada website. This list would also serve as a valuable resource to petitioners seeking to add an ingredient to an infant formula product, as they could easily identify which ingredients have already been accepted by Health Canada for addition to infant formula. Additionally, the guidance document would be updated to address current gaps, including providing a clear distinction between NIFIs and novel food for infants.

These improvements aim to enhance clarity and efficiency for adding NIFI to infant formula that are intended for sale in Canada. By establishing a robust regulatory framework, providing clear guidance, separating NIFI evaluations from infant formula submissions, and maintaining a public list of accepted new infant formula ingredients, Health Canada could effectively facilitate the introduction of safe NIFI while streamlining the regulatory process for manufacturers. These measures would help ensure transparency, support informed decision-making, and foster innovation in the development of infant formula.

4.1.3 Labelling requirements

The proposed labelling requirements for infant formula would aim to ensure that sufficient information is provided to caregivers to enable the safe use and preparation of these products while aligning with the Codex Standard for Infant Formula and Formulas for Special Medical Purposes Intended for Infants (Codex Standard 72-1981)Reference 24 and the WHO Code, where appropriate, to reduce the burden on manufacturers. To streamline the review process and minimize ambiguity, it is essential to establish comprehensive and transparent labelling requirements for these products. This will help ensure a more efficient review process by reducing unnecessary back-and-forth communications to clarify label information.

a) Nutrition information

The current nutrition labelling requirements and prohibitions for infant formula would continue to apply, including the prohibition on the use of an NFt and FOP nutrition symbol on the label. However, minor changes are proposed related to outdated requirements. This would include removing the requirement to declare the content of ash in the productReference 25, which may be confusing to caregivers as ash is not considered a nutrient, and its declaration is not required in several other jurisdictions.

In addition, to enhance clarity and to facilitate compliance and enforcement activities, it is proposed to align the units of measure for vitamins and mineral nutrients in the nutrition information on the label with the units specified in the compositional requirements.

b) Mandatory label statements

- Principal display panel requirements

Mandatory statements on the principal display panel help caregivers make informed decisions about the most appropriate infant formula to select, such as differentiating between formula intended for infants 0-6 months of age (often called starter formula) and for infants 6-12 months of age (often called follow-up formula), standard or specialized formulas, liquid concentrated or ready-to-feed formulas, and more. As such, the following information would be required on the principal display panel of an infant formula product:

- Age range of the intended user of the product (for example 0 to 12 months, 6 months and more)

- For products that deviate from the standard compositional requirements: indication of how the composition deviates from the standard requirements and the purpose for which the product is intended (such as phenylalanine free for the dietary management of phenylketonuria in infants)

- Statement and/or symbol related to the addition of water:

- For liquid concentrated infant formula: "Add water", as well as a symbol demonstrating the addition of water

- For ready-to-feed infant formula: "Do not add water"

- Indication of the product format (for example powder, liquid concentrated, liquid ready-to-feed, etc.)

- Indication of the protein source (for example cow milk-based infant formula, goat milk-based infant formula, soy-based infant formula etc.)

Requiring on the label the source of protein, the age range of the intended user of the product and an indication of how the composition deviates from the standard compositional requirements aligns with recommendations in Codex Standard 72-1981 that states that the source of protein in the product shall be clearly shown on the label and the product should be labelled in such a way to avoid any risk of confusion between infant formula, follow-up formula, and formula for special medical purposes.

- Directions for use, including the preparation, storage and disposal

Mandatory statements related to the preparation, storage and disposal of the product would also be required on the product label. Prescribing these statements in regulation would provide consistency for the caregiver. Specifically, it is proposed that the label include the following directions for use or similar statements (in words and pictures):

- Clean countertops, top of infant formula container and hands with soap and warm water before preparing formula.

- Boil bottles, nipples, utensils and preparation equipment in safe water to sterilize before use. Each bottle must be prepared individually.

- To prepare powdered and liquid concentrated formula:

- For healthy, full-term infants: Boil safe water for two minutes. Cool to between body and room temperature (37 - 25 degrees Celsius).

- For premature and low birth weight infants under two months of age and infants with a weakened immune system: Boil safe water for two minutes. Cool to 70 degrees Celsius (30 minutes).

- The formula must be shaken well just prior to feeding, and served at body temperature (37 degrees Celsius).

- If a bottle of prepared formula is to be stored prior to use, it must be refrigerated and used within 24 hours of preparation.

- Throw away any formula that has not been consumed within two hours after a feed has begun.

- Do not store infant formula containers at excessive temperatures. Opened powdered formula containers must be used within one month. Opened liquid concentrated formula containers and ready to feed formula containers must be used within 24 hours.

Note: Item 3b in this list is not applicable to infant formula that carry a contraindication statement on the label against the use of these formulas in premature and low birth weight infants under two months of age and infants with a weakened immune system.

It is proposed that the following statement be required on the label immediately before the directions for use:

- For all infant formula: "Your baby's health depends on carefully following preparation instructions"

It is also proposed that the following statements be required on the label in close proximity to the directions for use:

- For powdered or liquid concentrated infant formula: "Do not change proportions of powder or concentrate or add other food except on medical advice"

- For ready-to-feed infant formula: "Do not dilute or add any other food except on medical advice"

These mandatory statements help reinforce to the caregiver that infant formula must be prepared according to the directions for use on the label.

This proposal aligns with recommendations in the WHO Code and Codex Standard 72-1981 which states that the label should include adequate directions for the appropriate preparations and use of the product, including its storage and disposal, as well as a warning about the health risks of inappropriate preparation.

- Lot numbers

It is proposed to require the lot number on the label of all infant formula. This information is important in case of a product recall, so that affected products can be easily identified by retailers and caregivers and removed from the market.

- Protecting and promoting breastfeeding

It is proposed that infant formula meeting the standard compositional requirements be required to carry a statement of the superiority of breastfeeding on the label under the heading "Important Notice". This statement would not be required for infant formula that deviate from the standard compositional requirement, because those products are intended for infants with distinct nutrient requirements that may impact their ability to safely consume human milk. This mandatory statement aligns with the WHO Code, as well as Codex Standard 72-1981.

Prohibiting certain images and text from the label would help Canada adhere to the WHO Code, as well as Codex Standard 72-1981. These recommend prohibiting the use of pictures or text that may idealize the use of infant formula (for example, pictures of infants or parents holding infants) as they can undermine the message that breastfeeding is best for babies. These also recommend prohibiting statements identifying an ingredient in infant formula as a key component of human milk which are considered misleading given that there are many components in human milk that are equally important. It is proposed to prohibit the following on the label of all infant formula:

- Pictures of infants, or other pictures or text, which may idealize the use of infant formula

- The terms "humanized", "maternalized", "human milk oligosaccharide", "human milk identical oligosaccharide" or similar terms, words, or abbreviations

- Statements comparing infant formula or its ingredient(s) to human milk, including comparison of the levels of a nutrient in infant formula to the level of the same nutrient in human milk

- Cautionary statements

It is proposed that cautionary statements currently recommended in Health Canada guidance, and those recommended during the premarket review, be added to the FDR to ensure consistent wording across all infant formula regarding their safe use. It is proposed that all cautionary statements be grouped on the product label under the heading "Caution".

Burn injuries related to heating infant formula can lead to emergency room visits and be life threateningReference 26. It is therefore proposed that the following be included on the label:

- A statement about the risks associated with heating and reheating infant formula in the microwave, such as "Never heat formula in a microwave oven. Serious burns can result"

- A statement about testing the temperature of prepared infant formula prior to feeding to prevent scalding the infant's mouth, such as "Place a drop of formula onto the inside of your wrist. If you do not feel a temperature difference, the formula temperature is just right"

It is proposed that infant formula meeting the standard compositional requirements be required to include a statement to the effect that the infant formula is to be used only on the advice of a health care professional. Similar statements already appear on infant formula on the Canadian market, and this aligns with recommendations in Codex Standard 72-1981 and the WHO Code.

It is proposed that infant formula deviating from the standard compositional requirements be required to include a statement on the label indicating that the infant formula is to be used only under medical supervision. These infant formulas are formulated to meet the needs of infants with medical conditions. As such, they may not be safe for consumption by healthy term infants.

It is proposed that all milk-based lactose-free infant formula be required to include a contraindication statement on the label against the use of these formulas in infants with galactosemia. Lactose-free, milk-based infant formula still contains a small amount of residual lactose. For this reason, these formulas are contraindicated for infants with galactosemia.

It is proposed that all powdered infant formula with heat sensitive ingredients (such as probiotics) include a contraindication statement on the label against the use of these formulas in premature and low birth weight infants under two months of age and infants with a weakened immune system. For these infants, the use of previously boiled water, cooled to 70 degrees Celsius is required for the preparation of the formula to kill bacteria that could be harmful to immunocompromised infants. However, infant formula with heat sensitive ingredients often have directions for use to prepare the product using previously boiled water, cooled to lower temperatures.

- Prohibition on cross branding

A study by Richter et al., showed that parents frequently mentioned the similarities between the labelling of infant formula and toddler milk (currently regulated as nutritional supplements for children)Reference 27. This may be due to cross branding (for example, when labels on nutritional supplements for children have a color scheme or design similar to labels on infant formula). This marketing strategy makes it challenging for caregivers to differentiate between infant formula and nutritional supplements for children, which may result in infants being fed nutritional supplements for children, which could pose a risk to health.

Nutritional supplements for children are proposed to be regulated as formulated nutritional foods (FNF) for children (refer to subsection 5.3.1 Formulated nutritional foods for children). As such, it is proposed that cross branding infant formula and FNF for children be prohibited.

- Labelling exemptions

Infant formulas that deviate from the standard compositional requirements are specially formulated to address the specific needs of infants with certain medical conditions. Considering the unique nature and purpose of these formula variations, some of the mandatory labelling requirements may not be applicable or necessary. Therefore, it is proposed that a provision be added to the regulations for infant formula deviating from the standard compositional requirements that would provide an exemption to certain labelling requirements specific to infant formula, where there is a valid rationale.

- Changes to label text or images

It is proposed that changes to the text or images on infant formula labels require advance notification to Health Canada, a minimum of 60 days prior to their implementation. This proactive measure would ensure that Health Canada possesses the most current version of product labels available on the market. Furthermore, this timeline allows Health Canada to identify any potential concerns related to claims and indications of use.

4.1.4 Additional regulatory requirements for infant formula

a) Claims

It is proposed that existing prohibitions for disease risk reduction claims and therapeutic claimsReference 28 as well as restrictions for nutrient content claimsReference 29 for foods intended solely for children under 4 years of age be maintained for all infant formula.