Progress Update: Joint Union/Management Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion in the Public Service

ISBN: 978-0-660-08986-7

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada,

represented by the President of the Treasury Board, 2017

Table of contents

- Foreword

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- The Task Force’s progress to date

- Consultation and engagement strategy: have your say

- Looking forward

- Appendix A: members of the Task Force

- Appendix B: overview of existing initiatives on diversity and inclusion, best practices, and legislative changes in the federal public service and other jurisdictions

- Appendix C: engagement activities with interest groups and regional employees

Foreword

The members of the Joint Union/Management Task force on Diversity and Inclusion in the Public Service acknowledge the privilege and importance of their work. We are committed to delivering an impactful final report at the end of our mandate, one that will be relevant today and in the future and help lead the way for a real culture shift in Canada’s public service.

It takes leadership to recognize the need for change, and courage to take the steps required to make that change happen. The Task Force would like to thank the Honourable Scott Brison, President of the Treasury Board, for his leadership and courage in this important endeavour.

The work of the Task Force marks the first time the Government of Canada has examined diversity and inclusion across the federal public service. The Task Force acknowledges the collaboration between the employer and unions, and the support of the Task Force secretariat, in undertaking its work. It recognizes the importance of establishing a case for diversity and inclusion that goes beyond simple adherence to legislative obligations, and that stronger diversity and inclusion in the public service will lead to better decisions, the ability to attract and retain the best talent from all generations, and ultimately better results for Canadians.

This progress update is the first step in achieving the Task Force’s mandate, outlining its work accomplished so far and its early findings.

For the purposes of this update, diversity and inclusion are understood as follows:

- A diverse workforce in the public service consists of individuals who have a wide variety of identities, abilities, backgrounds, skills and perspectives that are representative of the Canadian population.

- An inclusive workplace is based on a foundation of fairness, equity and compassion, and welcomes, respects and leverages differences in identities, abilities, backgrounds, skills and perspectives.

The Task Force’s vision for diversity and inclusion in Canada’s public service is as follows:

- A world-class, representative public service that is defined by its diverse workforce and its welcoming and inclusive workplace that aligns with Canada’s evolving human rights context, and that is committed to innovation to achieve results

Executive summary

As Canada is poised to celebrate its 150th birthday, the Government of Canada is engaging its employees in conversations about strengthening diversity and inclusion in the federal public service.

Since it was launched on November 30, 2016, the Joint Union/Management Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion in the Public Service has met with the following to learn about opportunities, challenges and best practices:

- over 20 stakeholder groups representing 16 departments and agencies across the federal public service

- representatives from 15 private sector companies

- representatives from two provincial jurisdictions

The Task Force has also directly engaged employees through the following:

- an online survey distributed to 30 departments and agencies

- discussion forums planned with 19 employee networks and communities of practice across the country

The Task Force’s mandate is to:

- define diversity and inclusion in the public service

- establish a case for diversity and inclusion

- develop a framework and action plan to strengthen diversity and inclusion in the public service

This progress update outlines the Task Force’s key observations that will shape a framework and action plan to address the Task Force’s work before it issues its final report in fall 2017.

The Task Force is optimistic and energized by the opportunity to work collaboratively. The strength of the public service as an employer comes from having many levers at its disposal to support diversity and inclusion. These levers include:

- a broad legislative and policy framework to support the various elements of diversity and inclusion

- the commitment of the Clerk of the Privy Council and other senior leaders in the public service to make change happen

- the Prime Minister’s leadership in championing diversity and inclusion in Canadian society and around the world

Although more evidence and data are needed to gauge the public service’s performance in areas beyond employment equity (EE), there are some positive signs. As a whole, Canada’s public service continues to exceed workforce availability levels for representation among all four groups designated under the Employment Equity Act:

- women

- Aboriginal peoples See Footnote 1

- persons with disabilities

- members of visible minorities

However, there is strong evidence of chronic and systemic challenges that hinder diversity and inclusion in the public service. Many gaps in representation persist in the executive category; as a group, the very leaders who shape and influence the culture of federal organizations are not sufficiently diverse. Furthermore, in the most recent Public Service Employee Survey, Indigenous employees reported harassment and discrimination at twice the rate of other employees, with racism cited as the most frequent ground for discrimination.

Addressing these and other challenges described in this update becomes even more important in light of Canada’s changing demographics:

- immigration accounts for over two thirds of Canada’s population growth, with the majority being visible minorities

- an estimated 5% of Canadians identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender

- one in five Canadians will experience mental health challenges in their lifetime

- the millennial generation is forecast to make up 75% of the labour force in Canada in just over 10 years (2028)

- Canada’s Indigenous youth are the fastest-growing segment of the population

Key early observations

The Task Force is working to complete its analysis of issues raised in consultations that ended May 31, 2017. Based on its observations so far, the Task Force will examine potential action in four principal areas:

- Accountability: Departments and agencies are required to report publicly on elements of diversity such as EE, and some federal organizations report on their activities related to diversity and inclusion. However, there is no government-wide accountability framework that sets out principles and established measures of progress for diversity and inclusion. Although there has been headway on EE, poor results persist in key areas, such as in the executive category. Such gaps do not attract public attention or sufficient consequence to have remedied the challenges that are impeding progress. In fact, even the limited oversight on accountability has waned over the years; as an example, the Canadian Human Rights Commission, which monitors departmental compliance on EE, now conducts a review approximately every three years instead of annually.

- People management: There is evidence and a perception among equity-seeking groups that recruitment and people management policies and practices inhibit progress on diversity and inclusion. Hiring rates for people with disabilities are lower than for other employees, and there are higher drop-off rates as candidates move from applicant pool to job offer. Nearly a quarter of public servants believe that selection processes in their unit are not fair, and there are perceptions that members of equity groups languish in partially qualified pools of talent. The Task Force welcomes the important work of the Public Service Commission of Canada to study the impact of name-blind recruitment to address potential unconscious bias in recruitment decisions.

- Education and awareness: Frank and respectful conversations about diversity and inclusion must address the perceptions and concerns of all employees. Education and training is required to enhance the ability of the public service to leverage differences as a source of strength and innovation by effectively tapping into the talents of diverse groups. The Task Force believes that a fundamental shift in mindset must occur, from viewing diversity and inclusion as a legal, moral and social obligation to recognizing its potential to achieve results through creative solutions to problems. The most successful organizations in the world know that diversity and inclusion spur innovation, increase productivity and create a healthy, respectful workplace. In government, we must define what diversity and inclusion mean for a world-class public service, to help all employees understand, embrace and champion both aspects, especially as we confront challenges that demand a diversity of perspectives and collaborative approaches.

- An integrated approach: To change culture, an organization-wide approach is needed to:

- address concerns regarding recruitment and people management

- embed diversity and inclusion considerations in all aspects of public policy, from developing and implementing new policies and programs to their evaluation

The Ontario Public Service, for example, has developed practical tools to help employees create policies and programs that reflect the diverse needs of their clients.

Finally, the Task Force recognizes that diversity and inclusion must not be viewed in isolation. A diversity of people brings fresh ideas and perspectives to the workplace that can produce better results. But to realize such benefits, we must also change how we work, in other words, create an environment where all employees feel involved and respected, and where their ideas are welcomed and valued.

The Task Force looks forward to completing its work over the coming months, as it recognizes the potential to tap into the current momentum to strengthen diversity and inclusion throughout Canada’s public service.

“Canada has learned how to be strong not in spite of our differences, but because of them, and going forward, that capacity will be at the heart of both our success, and of what we offer the world.”

Introduction

Canada’s immense diversity is evident in the broad racial and ethnocultural makeup of its population. One fifth of Canadians were born outside of Canada, and its residents speak more than 200 languages. Immigration accounts for almost two thirds of population growth, with a significant majority being members of visible minorities. Statistics Canada projects that by 2031 close to one in three Canadians (31%) will be members of a visible minority and that almost one in two (45%) will be either an immigrant or a child of an immigrant.

“The diversity of our people and the ideas they generate are the source of our innovation.”

In addition:

- an estimated 5% of Canadians identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender See Footnote 2

- the millennial generation is forecast to make up 75% of the labour force in Canada in just over 10 years (2028) See Footnote 3

- one in five Canadians will experience mental health challenges in their lifetime

- Canada’s Indigenous youth are the fastest-growing segment of the population

Many countries have great diversity in their populations, so what sets Canada apart? There is a perception that Canada is a mosaic rather than a melting pot, where individuals can maintain their identities and still be part of the whole. This perception is partly reflected by:

- Canada’s robust legislative framework to protect individuals against discrimination and promote inclusion

- Canada’s willingness to open its doors to refugees

- national public awareness campaigns to eliminate the stigma of mental illness

- reconciliation efforts with Indigenous peoples

The federal government is Canada’s largest employer, with over 250,000 employees across the country and elsewhere. Although jobs in the public service are often associated with administration and policy work, Canada’s public servants are also trade negotiators, border security officers, scientists, engineers, marine biologists, doctors, nurses, veterinarians, park wardens, plumbers, electricians, and other skilled and unskilled tradespeople. They work on mountaintops, in the boreal forest, on ships and in helicopters, and in locations around the world.

As a public institution, the federal public service has an obligation to ensure that its employees are representative of the people it serves:

- The Public Service Employment Act recognizes that Canada will “gain from a public service…that is representative of Canada’s diversity” See Footnote 4

- There are legal obligations to meet representation levels for groups designated under the Employment Equity Act (women, Aboriginal peoples, persons with disabilities, members of visible minorities)

Without such representation and diversity of employees, decisions taken at the federal level cannot be said to reflect the perspectives of all Canadians.

Furthermore, research shows that diversity and inclusion allow organizations to increase the productivity of their human capital and better serve multiple client groups though recruiting, utilizing and retaining a diverse workforce, which spurs innovation through diverse experiences. See Footnote 5

“New thinking, innovative approaches, and keeping up with the evolving expectations of our citizens are fundamental…above all, diversity and inclusion can lead to better decision-making and better results for Canadians.”

One study See Footnote 6 considered an in-depth analysis of data from Statistics Canada’s Workplace Employee Survey. It revealed a significant positive relationship between ethnocultural diversity and increased productivity, with the strongest performance in sectors that depend on creativity and innovation.

This study also undertook roundtable discussions with more than 100 leading employers in Canada. These discussions showed a strong sense that governments and industry are focused more on numbers and not enough on inclusion. As one executive said, “For the last 20 years, we have been doing the same kinds of things: muscling through to get numbers on diversity, but we haven’t changed the infrastructure or environment that we are operating in.” The challenge, concluded the study, is to change the way we think and the way we work if we want to see the true benefits of diversity.

Diversity and inclusion have been firmly established as a priority of the Government of Canada by the Prime Minister and the Clerk of the Privy Council. In spring 2016, the President of the Treasury Board proposed to bargaining agents a joint union/management task force, modelled on the recent Joint Union/Management Task Force on Mental Health, to examine the issue of diversity and inclusion. On November 30, 2016, the Joint Union/Management Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion in the Public Service was established with a one-year mandate to:

- define diversity and inclusion in the public service

- establish a case for diversity and inclusion

- develop a framework and action plan to strengthen diversity and inclusion in the public service

The Task Force includes a Technical Committee, whose work is led by a Steering Committee See Footnote 7 that has equal representation from the employer and from bargaining agents. The Task Force members bring with them an extensive body of experience and knowledge.

The Task Force’s progress to date

To deliver on its mandate, Task Force members will draw from the following:

- a recently completed environmental scan

- engagement of public servants directly through an online survey of 30 departments and agencies

- discussion forums with networks and communities of practice

Environmental scan

As the first step toward understanding and defining diversity and inclusion in the public service, Task Force members conducted an environmental scan that included meetings with the following:

- over 20 stakeholder groups representing 16 departments and agencies across the public service

- representatives from 15 private sector institutions

- representatives from two provincial jurisdictions

Discussion involved the following:

- diversity and inclusion initiatives

- challenges

- data and monitoring tools

- barriers to inclusion

- best practices

- trends in the public and private sectors

Insights gained through this scan were complemented by research by the Task Force secretariat, which included an examination of two national jurisdictions that have population profiles that are similar to Canada’s (Australia and the UK).

What the Task Force has learned

Defining diversity and inclusion

The first part of the Task Force’s mandate is to define diversity and inclusion, as developing a common understanding of the concepts of diversity and inclusion is critical.

Diversity and inclusion are broadly understood as two distinct concepts:

- diversity, focusing on individuals who have differing talents and perspectives

- inclusion, focusing on the culture of the organization

Several organizations that the Task Force examined have developed definitions that are specific to their own contexts, but there was no single definition that captures the breadth of the concept of diversity in the context of the public service. Regarding inclusion, the challenge is to define how the workplace satisfies employees’ desire for “belongingness” and “uniqueness” simultaneously. See Footnote 8 Given these challenges, the Task Force believes it may be more useful to develop principles for diversity and inclusion rather than to arrive at definitions for them. The Task Force will continue to reflect on this issue in its ongoing work.

Legislative and policy foundations in Canada

Over the years, legislation and policies See Footnote 9 have been developed to support diversity and inclusion in Canada as a whole and in the public service in particular. For example, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, embedded in the Constitution Act, 1982, guarantees a right to equality for all Canadians.

“Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.”

The Canadian Human Rights Act prohibits discrimination on 11 grounds:

- race

- national or ethnic origin

- colour

- religion

- age

- sex (including pregnancy and childbearing)

- sexual orientation

- marital status

- family status

- mental or physical disability (including dependence on alcohol or drugs)

- pardoned criminal conviction

The application of the Canadian Human Rights Act is not limited to employment.

The Employment Equity Act requires every employer in its purview to implement EE. The act states that every employer must implement EE by:

- identifying and eliminating employment barriers against persons in designated groups that result from the employer’s employment systems, policies and practices that are not authorized by law

- instituting such positive policies and practices and making such reasonable accommodations as will ensure that persons in designated groups achieve a degree of representation in each occupational group in the employer’s workforce that reflects their representation in

- the Canadian workforce, or

- those segments of the Canadian workforce that are identifiable by qualification, eligibility or geography and from which the employer may reasonably be expected to draw employees

The Canadian Multiculturalism Act aims to preserve and enhance multiculturalism in Canada, requiring federal institutions to report annually on their activities to promote multiculturalism in federal workplaces.

The Official Languages Act stipulates that English and French are the official languages of Canada and that each has equality of status and equal rights and privileges as to their use in all institutions of Parliament and the Government of Canada.

The Public Service Employment Act recognizes the importance of a public service that is representative of Canada’s diversity, and that the public service can be used to support EE objectives in recruitment strategies. Examples are:

- limiting or expanding an area of selection to one or more EE-designated groups

- establishing and applying organizational need for diversity

- using a non-advertised process to achieve EE objectives

Following are the principal policies and other instruments that support diversity and inclusion in Canada’s public service:

- The Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector outlines the values and expected behaviours that guide public servants in all their professional duties. By committing to these values and adhering to the expected behaviours, public servants strengthen the ethical culture of the public sector and contribute to public confidence in all public institutions. Adherence to this Code is a condition of employment.

- The Employment Equity Policy supports equality in the federal public service so that no person is denied employment opportunities or benefits for reasons unrelated to ability.

- The Policy on Harassment Prevention and Resolution provides organizations with direction to foster a respectful workplace and address potential situations of harassment.

- The Policy on the Duty to Accommodate Persons with Disabilities in the Federal Public Service applies to all employees and to candidates in hiring processes.

International, provincial and other jurisdictions

A review of other jurisdictions shows that Canada has a strong legislative and policy foundation that supports diversity and inclusion. For example, although Australia and the UK monitor representation of specific groups, neither country has benchmarks such as workforce availability mandated in legislation. See Footnote 10 In both countries, the focus in legislation is on creating an inclusive and barrier-free workplace.

In Australia, groups mentioned in legislation are as follows:

- Aboriginal peoples

- women

- people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds

- mature workers

- young people

- caregivers See Footnote 11

In the UK, the Equality Act 2010 includes gender reassignment as one of the grounds on which discrimination is prohibited.

Canada’s provinces and territories are not covered by the Employment Equity Act. Each has varying levels of structures, programs and initiatives for persons with disabilities, often in response to specific legislation where accessibility is a consideration. The Ontario Public Service (OPS) has for many years been recognized as one of “Canada’s Best Diversity Employers.” It has established a Diversity Office that is responsible for transforming the OPS into a more diverse, accessible and inclusive organization that supports all employees in reaching their full potential. Among the OPS’s key initiatives is its use of an “inclusion lens” for reviewing policies, tools and programs when they are being developed.

Canada’s banking sector is also considered a leader in diversity and inclusion, having gone beyond the four EE groups set out in the Employment Equity Act to develop specific initiatives for the following:

- newcomers and immigrants

- lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning and two-spirit (LGBTQ2+) groups

- in the case of one organization, veterans

Positive Space: In 2016, a group of federal public servants received a Public Service Award of Excellence for their work on the Positive Space initiative, which is a grassroots movement striving for the well-being, safety and inclusion of people who identify as gender-diverse or sexually diverse. Over 1,000 volunteers have been trained as champions and ambassadors of workplace inclusion.

In assessing the approaches of other jurisdictions, the Task Force has determined that the following are critical to making progress on diversity and inclusion:

- commitment, accountability and support of senior leadership

- organization-wide education and awareness

- strategies that are integrated across the organization, including tools to support considerations for diversity and inclusion in all decision making

- measurement of progress

- investment of resources

- recognition and effective harnessing of the talents of new Canadians

- culture change

Federal departments and agencies

The Task Force recognizes the momentum and growing engagement of leaders and employees in Canada’s federal public service in supporting diversity and inclusion in the workplace. However, in the absence of a government-wide framework and approach, these efforts remain disjointed, and engagement is inconsistent.

There are many initiatives in the public service to promote diversity and inclusion. But in the absence of established goals, data and performance measures, it is difficult to determine progress. There is concern over whether current initiatives, by themselves, will reduce or eliminate systemic barriers.

Name-blind recruitment: The Public Service Commission of Canada is undertaking a pilot on the sustainability and effectiveness of applying name-blind recruitment techniques in the federal public service. The pilot project will conceal names and other information (email addresses, education institution, country of origin of job applicant, and EE information). It will compare outcomes associated with traditional screening with screening in which managers are blinded to this applicant information. External selection processes from a range of departments will be part of the pilot, and the results will be used to inform further discussions in this area.

Indigenous Summer Youth Employment Opportunity: The Government of Canada partnered with the Assembly of First Nations in 2016 to place 30 Indigenous post-secondary students from across the country in meaningful summer jobs in the National Capital Region. The initiative was given an 88% approval rating by participants, with two thirds of the students receiving an offer of some form of continuing employment after the pilot ended. The program was expanded to include over 100 summer students in 2017, with the potential to include the regions in the future to help bring job opportunities closer to Indigenous communities.

Departments and agencies are measuring progress using various tools, including the following:

- the Canadian Human Rights Commission’s Human Rights Maturity Model and other diversity continuums, as a base to assess annual progress

- quarterly reports to executive committees on hiring, representation, promotions, acting opportunities and separation data for EE-designated groups

- performance management agreements that reflect goals for diversity and inclusion

- departmental surveys of employees’ experiences and perceptions

- analysis of mobility trends for EE groups

A few departments and agencies share such information with bargaining agents.

Examples of recent initiatives in the federal public services are as follows:

- Indigenous Youth Summer Employment Opportunity

- Interdepartmental Collaboration Circle on Indigenous Representation in the Federal Public Service

- Name-Blind Recruitment Pilot Project

- Positive Space initiatives

- Youth with Disabilities Summer Employment Opportunity

Details on these and other initiatives, best practices and legislative changes underway are in Appendix B.

Progress and challenges

Progress on employment equity

Since the adoption of the Employment Equity Act and the institution of the Treasury Board’s Employment Equity Policy, the public service has made significant progress in addressing equity issues over the past 10 years, particularly in representation levels for members of visible minorities (a 75% increase) and Indigenous peoples (a 25% increase). The federal public service continues to be a leader in EE, comparing favourably with the private sector.

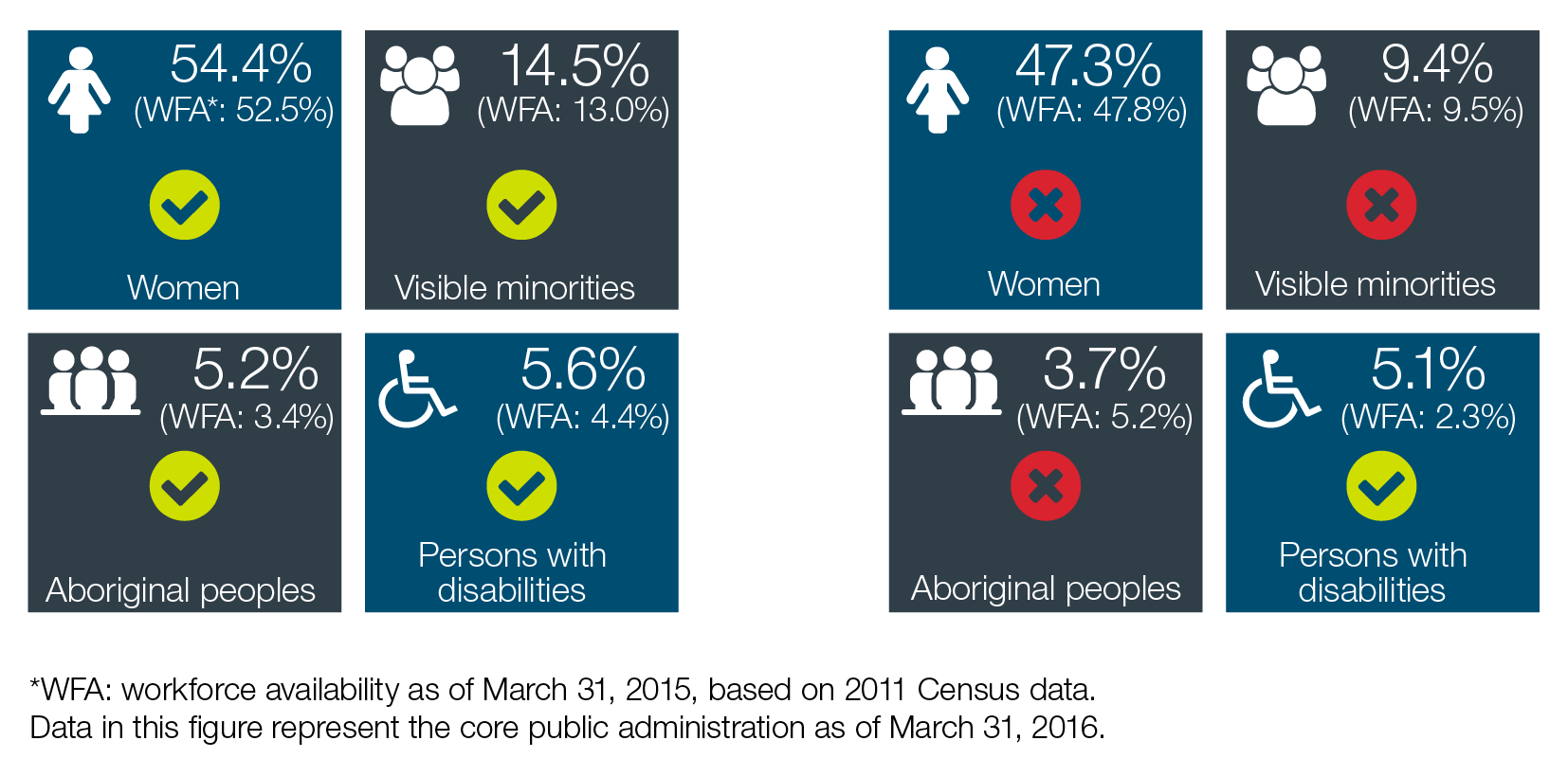

For the fourth consecutive year, See Footnote 12 all four EE groups in the federal public service exceeded their workforce availability. However, gaps persist in key areas, particularly in the executive category, where representation levels do not meet workforce availability for women, Indigenous peoples and members of visible minorities.

Figure 1 - Text version

The portrait of the public service in the 2015 to 2016 fiscal year is summarized as follows:

- Representation of women increased slightly from 54.3% to 54.4%, surpassing their workforce availability of 52.5%.

- Representation of members of visible minorities increased from 13.8% to 14.5%, surpassing their workforce availability of 13.0%.

- Representation of Aboriginal peoples increased slightly from 5.1% to 5.2%, surpassing their workforce availability of 3.4%.

- Representation of persons with disabilities continued to maintain their representation at 5.6%, surpassing their workforce availability of 4.4%.

Within the Executive Group, progress was made, but representation rates still did not meet workforce availability for three of the four designated groups:

- Women increased their representation from 46.4% to 47.3%, slightly below their workforce availability of 47.8%.

- Members of visible minorities increased their representation from 8.8% to 9.4%, almost matching their workforce availability of 9.5%.

- Representation of Aboriginal peoples increased their representation from 3.4% to 3.7% but remains below their workforce availability of 5.2%.

- Representation of persons with disabilities decreased from 5.3% to 5.1%, which continued to surpass their workforce availability of 2.3%.

There are also gaps in EE representation in the following:

- specific operational categories (technical, scientific and professional occupations for some EE groups)

- certain regions

- some departments and agencies

In addition, EE groups are overrepresented in lower ranks and in lower salary ranges.

For persons with disabilities, recruitment rates are low and separation rates are high. See Footnote 13 Although representation levels are being met, this may be due to disabilities that are developed after hiring, which does not respect the spirit of legislation in removing barriers to hiring. For Indigenous peoples, retention rates continue to be low.

Key challenges

The latest results of the Public Service Employee Survey See Footnote 14 show that there continue to be high levels of perceived discrimination and harassment among EE groups, with employees fearing retaliation if their concerns are raised.

Challenges continue to occur in the workplace for employees who are affected by mental health problems, and for hiring managers who require more and better tools to understand and support the needs of such employees.

The requirement of citizenship or permanent residency for public sector jobs, and the lack of recognition or difficulty in having foreign credentials recognized, precludes hiring of many qualified visible minorities in the public service. Furthermore, minority groups who are interested in and qualified to work in the federal public service face many obstacles, among them:

- self-censoring in applying for government jobs based on early rejection experience

- being “trapped” in low-paying jobs that require long hours, which can make candidates unable to respond quickly to public service job postings, which often have very tight application deadlines

Foreign-born Canadians can also face serious challenges in articulating their qualifications and experience in one of Canada’s official languages, and in their knowledge of terminology and expressions that are specific to the federal public service. Such challenges put them at a significant disadvantage to native English- or French-speaking applicants.

Other EE issues include insufficient workplace childcare and the lack of a federal policy on domestic violence, both of which affect women disproportionately.

Frequently cited barriers to diversity and inclusion raised during the environmental scan were:

- perceived unfairness of the staffing process

- insufficient education and training in the public service about cultural awareness and sensitivity

- conscious and unconscious bias on the part of hiring managers

In addition, intersectionality, which is membership in more than one equity-seeking group, together with limited understanding of the multi-generational impacts of the residential school system, exacerbates barriers and requires further exploration.

Clustering of EE-designated group members at certain departments (for example, Indigenous peoples at Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada) presents a challenge, as these departments contribute to raising overall representation rates, masking poor performance in departments that have chronic under-representation. An inconsistent and insufficient level of accommodation provided to persons with disabilities was frequently cited as a barrier that prevented full participation of persons with disabilities in the workplace. Limited access to second-language training was identified as a barrier to employment and career progression by members of visible minorities and Indigenous peoples.

“20% of Canadians will personally experience a mental health issue in their lifetime.”

The need for stronger leadership and accountability (including insufficient oversight for compliance with existing legislation), application of existing policies, and data-gathering procedures were viewed as significant issues. EE data collected and publicly released has been insufficient to determine whether initiatives have been successful, and some departments often do not fully follow the consultation and collaboration requirements under section 15(3) of the Employment Equity Act. Under the Public Service Commission of Canada’s New Direction in Staffing appointment framework and oversight model, departments have more flexibility and discretion in staffing without additional oversight. Over the past decade, the Canadian Human Rights Commission (CHRC) has committed fewer resources and undertaken fewer streamlined audits, resulting in a dilution of oversight to monitor compliance with the act. There is also a perception that the CHRC’s maturity model, which is a self-auditing tool recommended for use by departments to measure performance, does not allow sufficient input from employees at the grassroots level.

Finally, although the purpose of EE overlaps with diversity and inclusion, as both work to achieve equality in the workplace, a significant challenge arises from concerns that broader diversity and inclusion may reduce the focus on EE.

Workforce availability

The Task Force is particularly interested in how workforce availability (WFA) benchmarks are used to measure representation among EE groups. The Task Force has two main concerns:

- WFA benchmarks lag significantly behind changes in Canada’s population. Current benchmarks are based on 2011 Census data, as it will take as long as three years to calculate new WFA benchmarks from 2016 Census data. Meanwhile, the Canadian population grew by 5% between 2011 and 2016, and growth in major metropolitan centres, where public sector jobs are concentrated, grew even faster. The composition of the population has also changed. Visible minorities represented 16.2% of the population in 2006, grew to 19.1% in 2011 and to 22.0% in 2016, and are projected to reach 31.0% by 2031. Over 51% of visible minorities are women.

- WFA estimates are based on populations of Canadian citizens who are available to work in a particular industry or job. Qualified permanent residents are excluded from WFA estimates to better reflect the actual pool of talent from which the government tends to hire. In other words, preference is given to Canadian citizens, although permanent residents can apply.

The Task Force notes that benchmarks do not accurately depict the diversity of the total population. The benchmarks exclude qualified individuals in EE groups such as visible minorities, many of whom are permanent residents, who represent an increasingly large segment of Canadian society. Furthermore, visible minorities are more likely than the general population to have post-secondary education (38.2% of visible minorities, compared with 25.9% of the general population), yet their employment prospects in the federal public service are much lower than for the general public.

Broader diversity

Although the Canadian Human Rights Act and other instruments such as the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector support broader diversity in the public service, the legislative framework under the Employment Equity Act and the Public Service Employment Act covers only the four EE-designated groups. As a result, other minority groups, such as those identifying as LGBTQ2+ and which tend to face barriers that are similar to those faced by EE groups, have not been at the core of efforts to promote and strengthen diversity in the public service (although there have been recent efforts to engage the LGBTQ2+ community, such as the Positive Space initiative). Age, culture, religion and other characteristics could be used to define other subsets of employees who perceive discrimination, harassment and other barriers in the workplace. Existing tools such as the Management Accountability Framework and performance management agreements are not perceived to be effective in addressing situations where diversity and inclusion or EE goals are not being met.

Barriers and areas for action

Based on its work to date, the Task Force has identified four overall areas that represent what needs action regarding diversity and inclusion:

- accountability

- effective people management (recruitment, representation, retention and staffing)

- education and awareness

- an integrated approach to diversity and inclusion

The Task Force is examining each of these areas for potential action.

Accountability

Being accountable is to demonstrate and take responsibility for results, and how they are achieved, in light of agreed-upon expectations. See Footnote 15

There appears to be inconsistent implementation and oversight of initiatives for diversity, inclusion and EE across the federal public service. Successful initiatives occur in organizations where:

- senior management indicates that action is a priority

- action is supported by dedicated resources (in time and money)

- there is ongoing monitoring of progress throughout the organization

The Task Force believes there are opportunities to strengthen leadership and oversight in departments and central agencies, Crown corporations, and other government institutions. For example, deputy heads could ensure that diversity and inclusion objectives are integrated into accountability frameworks as well as performance assessments of all managers. They could ensure that selection boards are composed of diverse members who are trained to promote diversity and inclusion at all stages of the staffing process. The Task Force notes that initiatives such as name-blind recruitment and Positive Space training occur because of committed leadership.

Clear accountability at all levels is critical in order for an organization-wide framework for diversity and inclusion to succeed. The Task Force will continue to consider ways to strengthen the government’s accountability framework for broader diversity and inclusion throughout the federal public service.

The Task Force will provide recommendations for enhanced accountability, monitoring and oversight to support diversity and inclusion in the federal public service.

Effective people management: recruitment, representation, retention and staffing

The environmental scan revealed that equity-seeking groups perceived gaps in recruitment, staffing and other people management practices that inhibit diversity and inclusion (for example, mechanisms for selection for training, for complaints and for recourse). There is also the perception that members of equity-seeking groups qualify for positions and then languish in partially qualified pools of talent at disproportionately higher rates. Finally, “right fit” assessments and the failure to use the flexibility provided in legislation that promotes diversity were frequently cited as barriers to establishing a more diverse and inclusive public service. These observations show that there are barriers caused by limiting discussion of difficult issues and through failing to resolve challenges that employees encounter at each stage of the employment process.

Managing people effectively is essential to achieving diversity and inclusion. The implementation of the Public Service Modernization Act and the Public Service Employment Act of 2005 changed the legal requirements for staffing in the public service, with a view to reducing regulatory requirements and increasing flexibility for hiring managers. However, there is a lack of confidence in the fairness of staffing processes. There is also a lack of trust that hiring managers are executing their people management responsibilities consistently in support of diversity and inclusion.

The Task Force will continue to examine people management and provide recommendations to:

- identify and take corrective action where individual biases can negatively affect people management processes

- increase transparency and accountability at each stage of the employment process

- identify measures for greater accountability, monitoring and oversight to support diversity and inclusion in the public service

Education and awareness

“It is imperative to appreciate that diversity and inclusion are not only moral and social imperatives but business imperatives as well.”

A more diverse workforce and a more inclusive workplace can be achieved only through fundamental culture change and employee engagement throughout the federal public service. To achieve such change, it is important to acknowledge how environments and personal life experiences can shape attitudes and beliefs, sometimes predisposing individuals to conscious and unconscious bias against particular groups. The public service must be dedicated to building workplaces that thrive on the contributions of all public servants, and the collective goal should be to foster an environment of dignity and respect in which everyone feels welcome, included and valued. It is imperative to appreciate that diversity and inclusion are not only moral and social imperatives but business imperatives as well.

Education is integral to any strategy for culture change in Canada’s public service. Education on diversity and inclusion should include training that addresses:

- the public service’s legal and policy framework for diversity and inclusion

- intersectional impacts of the existing culture on individuals who face multiple forms of discrimination

- systemic barriers in hiring, career development, promotion and other workplace practices

Training must also enhance the ability of the public service to leverage cultural and other differences as a source of strength and innovation by tapping into the talents of diverse groups.

The Task Force will provide recommendations to ensure that training fosters changes to culture and practice that promote diversity and inclusion in the public service.

An integrated approach to diversity and inclusion

Ultimately, to shift its culture, the government should develop a strategy that addresses gaps in all areas simultaneously. For the strategy to remain relevant, a sustainable approach is needed to ensure the evolution of public service culture with changes to Canada’s demographics and human rights context. Such an approach will reflect consideration for diversity and inclusion in all decisions about policies, programs and managing people, similar to how gender-based analysis promotes considerations for gender.

Successful organizations that have a well-evolved diversity and inclusion strategy, such as the Ontario Public Service, use an “inclusion lens” in their work with stakeholders, partners and the public. The lens encourages taking an inclusive approach when making policy decisions and in delivering programs. It is also a tool that will allow the federal public service to maximize its talented and diverse workforce.

The Task Force will design and propose a diversity and inclusion lens for the public service.

The areas identified above are interrelated. For example, giving hiring managers more flexibility in recruitment and staffing, without raising their awareness of the impacts of their decisions on individuals and on the culture of the public service, highlights the need for more education and training. The existing situation has persisted due to insufficient oversight to enforce principles intended to shape a public service culture that is representative, diverse and inclusive, which shows gaps in accountability and people management. Similarly, the success of using a diversity and inclusion lens is linked to actions on accountability, education, empowerment and engagement.

Consultation and engagement strategy: have your say

The Task Force has been consulting throughout the public service. Its objective is to listen and to learn about public servants’ perspectives on key issues and barriers, and to learn what contributes to a diverse and inclusive workplace. The Task Force has used two methods for its consultations:

- an online survey of employees in 30 departments and agencies

- a series of discussion forums with employee networks and communities of practice

Consultations are planned to be completed by May 31, 2017 (see Appendix C for further details).

Early findings from the consultations validate what the Task Force heard and learned from its environmental scan. Concerns tend to fall into the areas of leadership accountability, education and awareness, and people management. Additional themes are:

- the need to review the public service’s mechanism for self-identification and the accuracy of resulting data

- suggestions that EE committees play a greater role in staffing and recruitment

- making selection boards for hiring more diverse

- the need to invest more resources to support the public service’s initiatives on diversity and inclusion

Looking forward

The Task Force will review and reflect on the rich and robust discussions it has been having with various groups and individuals over the past six months, along with the research and information it has accumulated. The Task Force’s actions and recommendations will be informed by:

- decisions based on evidence

- a commitment to reflect views and perspectives gained though the Task Force’s consultations with employees and stakeholders

- the transparency of the Task Force’s processes

- the view that taking an integrated approach to diversity and inclusion is paramount to progress

The Task Force hopes that its work will start a long-term process of culture change in the public service, one that leads to a workforce that is fully representative of Canada’s diversity and a workspace that is inclusive of the rich differences that make up this diversity.

The Task Force is passionate and optimistic that the course outlined in this update will lead to the successful completion of its mandate. The Task Force’s final report will be delivered to the Honourable Scott Brison, President of the Treasury Board, in fall 2017.

Appendix A: members of the Task Force

| Name | Title | Organization |

|---|---|---|

| Steering Committee | ||

| Larry Rousseau, Steering Committee Co-chair |

Regional Executive Vice-President for the National Capital Region | Public Service Alliance of Canada |

| Margaret Van Amelsvoort-Thoms, Steering Committee Co-chair |

Executive Director, People Management and Community Engagement | Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer |

| Technical Committee | ||

| Bargaining Agent | ||

| Waheed Khan, Technical Committee Co-chair |

Employment Equity and Inclusiveness Champion | Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada |

| Melanie Bejzyk | Legal Officer | Professional Association of Foreign Service Officers |

| Karen Brook | Labour Relations Officer | Canadian Association of Professional Employees |

| Andrée Côté | Women’s and Human Rights Officer | Public Service Alliance of Canada |

| Michael Desautels | Human Rights and Aboriginal Rights Program Officer | Public Service Alliance of Canada |

| Seema Lamba | Human Rights Programs Officer | Public Service Alliance of Canada |

| Lionel Siniyunguruza | Research Officer | Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada |

| Employer | ||

| Louise Mignault, Technical Committee Co-chair |

Senior Director, Diversity and Inclusion | Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer |

| Sonja Crosby | Manager and Champion of the Diversity Network | Public Service and Procurement Canada |

| Cheryl Grant | Director General, Policy Coordination and Planning | Health Canada |

| Nadine Huggins | Director and Executive Secretary to the Interdepartmental Circles on Indigenous Representation | Public Safety Canada |

| Andrea Markowski | District Director and Positive Space Champion | Correctional Service Canada and Positive Space Network |

| Manjeet Sethi | Director General, Mental Health Branch | Correctional Service Canada |

| Executive Community | ||

| Debbie Winker | Visiting Executive | Association of Professional Executives of the Public Service of Canada |

Appendix B: overview of existing initiatives on diversity and inclusion, best practices, and legislative changes in the federal public service and other jurisdictions

While conducting its environmental scan, the Task Force was impressed by the breadth of action and concrete steps taken by many organizations to support diversity and inclusion, both within and outside the federal public service. Following are examples of existing initiatives and best practices.

1. Programs and initiatives

(The following are listed in no particular order)

- “Positive Space” initiative

-

Positive Space is grassroots movement striving for the well-being, safety and inclusion of people who identify as gender-diverse and sexually diverse. The Positive Space initiative provides training to volunteers who become champions or ambassadors of workplace inclusion by displaying identifiers, offering support to colleagues and raising awareness. Numerous federal departments and agencies have launched the Positive Space initiative. It is estimated that over 1,000 public servants have been trained in the initiative to date. There is a growing group of qualified trainers, and the Positive Space group on GCconnex has over 400 members. In 2016, a group of public servants received a Public Service Award of Excellence for their early work on the Positive Space initiative in the federal public service.

- Ontario Public Service

-

The Ontario Public Service (OPS) has positioned itself as leader in diversity and inclusion. The OPS has a solid governance structure, comprehensive training and tools, such as its inclusion lens, and a three-year inclusion strategy plan called “Inclusion Now!”that sets out clear priorities. It has established a Diversity Office within the Government of Ontario’s Cabinet Office (equivalent to the Privy Council Office), which has over 30 employees.

- Indigenous Youth Summer Employment Opportunity

-

The objective of this initiative is to strengthen representation, recruitment, talent development and retention of Indigenous youth through targeted recruitment and workplace measures to support onboarding and overall work experience. The pilot was launched in the 2017 fiscal year with 30 participants and will continue in 2018 fiscal year with over 100 participants.

- Name-Blind Recruitment

-

This pilot project was launched in April 2017 and involves a range of federal departments to review and test new tools and ways to strengthen inclusive recruitment. The project will compare outcomes of traditional screening and of screening in which managers are blinded to the applicant’s name and other information to determine whether unconscious bias occurs during the hiring process. Results of the project will inform further work in this area.

- LiveWorkPlay

-

This is a charitable organization for people with disabilities. Its mission is to help the community welcome people who have intellectual disabilities. This organization is partnering with federal departments for pilot projects on employment.

- Interdepartmental Collaboration Circle on Indigenous Representation in the Federal Public Service

-

This group has just released an interim report that examines the challenges and opportunities that are specific to Indigenous employees, together with proposed actions toward an end state where Indigenous peoples who seek and who have a public service career enjoy a feeling of well-being resulting from inclusion and respect.

- Pilimmaksaivik

-

This initiative seeks fair Inuit representation in Government of Canada positions in Nunavut (Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency).

- Canada’s Employment Equity Regulations

-

Employment and Social Development Canada is undertaking a review of these regulations, and is developing proposed new legislation on accessibility.

- Bill C-16

-

This Bill would amend the Canadian Human Rights Act to add gender identity and gender expression to the list of prohibited grounds of discrimination. It would also amend the Criminal Code to extend existing protection against hate propaganda to the same group.

- Gender-Based Analysis

-

This initiative is led by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and Status of Women Canada.

- Adaptive Technology Procurement

-

Led by Public Services and Procurement Canada, this initiative’s objective is to improve access to facilities, programs and services for people with disabilities.

- Public Service Employee Survey

-

Questions that are specific to diversity and inclusion have been added to the 2017 survey.

- Canada School of Public Service

-

The School is seeking to strengthen diversity and inclusion elements in its onboarding training for new public servants.

- Youth with Disabilities Summer Employment Opportunity

-

This pilot recruitment initiative will hire post-secondary students who self-identify as having a disability, for a period of up to 14 weeks, in the National Capital Region. Seven departments will participate in the pilot. This initiative is modelled on the Indigenous Youth Summer Employment Opportunity.

- Executive Leadership Development Program

-

This initiative is to accelerate the development of high-potential leaders from diverse talent pools. Diversity and inclusiveness are also elements of the program’s curriculum.

- Aboriginal Leadership Development Initiative

-

Led by Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, this initiative has been developed as a result of the Deputy Minister’s Aboriginal Workforce Initiative in 2008 to support developmental opportunities for Indigenous employees.

2. Initiatives undertaken by departments and other organizations

(The following are listed in no particular order.)

The Task Force has observed that the following are best practices:

- providing training material on diversity and inclusion for employees and managers, including:

- interactive tools

- informative brochures and other products

- hiring professional consultants to provide hands-on training

- offering courses on EE and diversity

- presenting themed events that highlight various cultural days, including:

- sharing of cultural calendars and diversity calendars

- “lunch and learn” sessions

- potluck events

- cultural days

- holding events and ceremonies planned for designated days, weeks and months (examples are International Women’s Day, Pride Week and Black History Month)

- distributing newsletters and pamphlets on EE, diversity and inclusion

- establishing new committees or tasking existing ones to examine issues related to EE, diversity and inclusion

- developing action plans for EE, diversity and inclusion

- developing measurement and accountability frameworks for diversity and inclusion, including:

- goals for EE, diversity and inclusion in performance management agreements

- objectives for EE, diversity and inclusion that are beyond legislative imperatives

- developing departmental surveys on diversity and inclusion (for example, LGBTQ2+)

- conducting mobility trends analyses

- engaging EE networks and other networks in internal policy work and design

- developing learning programs for combatting discrimination and harassment

- making it mandatory for selection board members to review the online interviewing guide developed by the Personnel Psychology Centre, which addresses potential for unconscious bias

- hiring an expert on the duty to accommodate on full-time basis

- requiring participants in talent development programs to contribute to or participate in existing EE and diversity networks or committees

Appendix C: engagement activities with interest groups and regional employees

| Date (2017) | Interest Group | Method | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| March 26, 27 | National Equity Conference, Public Service Alliance of Canada | Discussion forums | Toronto |

| March 29 | Human Resources Council | Discussion forum | Ottawa |

| April 10 | Champions and Chairs Circle for Indigenous People | Written recommendations from interim report: Interdepartmental Collaboration Circle on Indigenous Representation in the Federal Public Service | Ottawa |

| April 13 | Interdepartmental Network on Employment Equity | Discussion forum | Ottawa |

| April 18 | British Columbia Region | Discussion forum | Vancouver |

| April 20 | Community of Federal Visible Minorities | Discussion forum | Ottawa |

| April 28 | LGBTQ2+ community | Discussion forum | Ottawa |

| May 10 | Atlantic Region | Discussion forums | Halifax and Moncton |

| May 12 | Atlantic Federal Council | Presentation | Moncton |

| May 16 | National Women’s Network | Discussion forum | Ottawa |

| May 18 | Quebec Region | Discussion forums | Montréal |

| May 19 | Federal Youth Network | Discussion forum | Ottawa |

| May 24 | Prairies Region | Discussion forums | Winnipeg, Calgary, Saskatoon and Regina |

| May 25 | Ontario Region | Discussion forum | Toronto |

| May 30 | National Managers’ Community | Discussion forum | Ottawa |

| May 31 | Persons with Disabilities Chairs and Champions Committee | Discussion forum | Ottawa |

Page details

- Date modified: