Recovery Strategy for the Northern Madtom (Noturus stigmosus) in Canada (Proposed)-2012

January 2012

- Preface

- Responsible jurisdictions

- Authors

- Acknowledgements

- Strategic environmental assessment statement

- Executive summary

- 1. Background

- 2. Recovery

- 2.1 Recovery feasibility

- 2.2 Recovery goals

- 2.3 Population and distribution objective(s)

- 2.4 Recovery objectives

- 2.5 Approaches recommended to meet recovery objectives

- 2.6 Performance measures

- 2.7 Critical habitat

- 2.7.1 General identification of the Northern Madtom’s critical habitat

- 2.7.2 Information and methods used to identify critical habitat

- 2.7.3 Identification of critical habitat: biophysical function, features and their attributes

- 2.7.4 Identification of critical habitat: geospatial

- 2.7.5. Schedule of studies to identify critical habitat

- 2.7.6. Examples of activities likely to result in the destruction of critical habitat

- 2.8 Existing and recommended approaches to habitat protection

- 2.9 Effects on other species

- 2.10 Recommended approach for recovery implementation

- 2.11 Statement on action plans

- 3. References

- 4. Recovery team members

- Appendix 1. Record of cooperation and consultation

- Figure 1. The Northern Madtom (Noturus stigmosus)

- Figure 2. Global range of the Northern Madtom

- Figure 3. Canadian range of the Northern Madtom

- Figure 4. Critical habitat identified for the Northern Madtom within the Thames River

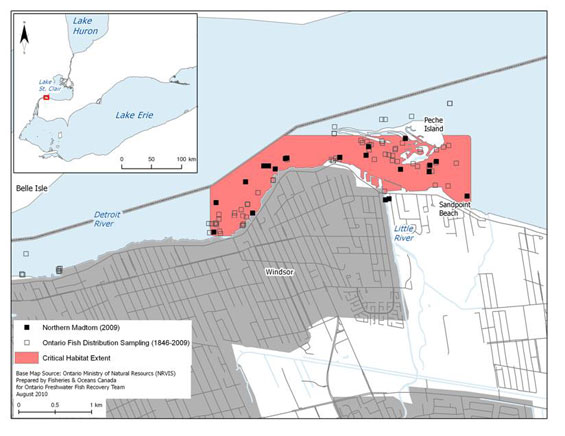

- Figure 5a. Critical habitat identified for the Northern Madtom within the Detroit River near Peche Island

- Figure 5b. Critical habitat identified for the Northern Madtom within the Detroit River near Fighting Island

- Table 1. Canadian and U.S. national and provincial/state heritage status ranks for the Northern Madtom (NatureServe 2009)

- Table 2. Threat classification table for Northern Madtom

- Table 3. Summary of recent fish surveys in areas of Northern Madtom occurrence (adapted from EERT 2008)

- Table 4.Recovery planning table – research and monitoring

- Table 5. Recovery planning table – management and coordination

- Table 6. Recovery planning table – stewardship, outreach and awareness

- Table 7. Performance measures for evaluating the achievement of recovery objectives

- Table 8. Essential functions, features and attributes of critical habitat for each life-stage of the Northern Madtom*

- Table 9. Comparison of the area of critical habitat identified (km2) for each Northern Madtom population, relative to the estimated minimum area for population viability (MAPV)*

- Table 10. Schedule of studies to identify critical habitat

- Table 11. Human activities likely to result in the destruction of critical habitat for Northern Madtom

Northern Madtom

SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003 and one of its purposes is “to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity.”

In the context of species at risk conservation, recovery is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of the species’ persistence in the wild. A species will be considered recovered when its long-term persistence in the wild has been secured.

A recovery strategy is a planning document that identifies what needs to be done to arrest or reverse the decline of a species. It sets goals and objectives and identifies the main areas of activities to be undertaken. Detailed planning is done at the action plan stage.

Recovery strategy development is a commitment of all provinces and territories and of three federal agencies -- Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada -- under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk. Sections 37–46 of SARA outline both the required content and the process for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Depending on the status of the species and when it was assessed, a recovery strategy has to be developed within one to two years after the species is added to the List of Wildlife Species at Risk. Three to four years is allowed for those species that were automatically listed when SARA came into force.

In most cases, one or more action plans will be developed to define and guide implementation of the recovery strategy. Nevertheless, directions set in the recovery strategy are sufficient to begin involving communities, land users, and conservationists in recovery implementation. Cost-effective measures to prevent the reduction or loss of the species should not be postponed for lack of full scientific certainty.

This series presents the recovery strategies prepared or adopted by the federal government under SARA. New documents will be added regularly as species get listed and as strategies are updated.

To learn more about the Species at Risk Act and recovery initiatives, please consult the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry.

Edwards, A.L., A.Y. Laurin, and S.K. Staton. 2011. Recovery Strategy for the Northern Madtom (Noturus stigmosus) in Canada [Proposed]. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ottawa. viii +42 pp.

Additional copies can be downloaded from the SAR Public Registry.

Cover illustration: Northern Madtom – © Joseph R. Tomelleri

Également disponible en français sous le titre

« Programme de rétablissement du chat-fou du nord (Noturus stigmosus) au Canada (proposition) »

©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, 2011. All rights reserved.

ISBN

Catalogue Number

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

The Northern Madtom is a freshwater fish and is under the responsibility of the federal government. The Species at Risk Act (SARA, Section 37) requires the competent minister to prepare recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered and Threatened species. The Northern Madtom was listed as Endangered under SARA in June 2003. The development of this recovery strategy was led by Fisheries and Oceans Canada – Central and Arctic Region in cooperation and consultation with many individuals, organizations and government agencies, as indicated below. The strategy meets SARA requirements in terms of content and process (Sections 39-41).

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy and will not be achieved by Fisheries and Oceans Canada or any other party alone. This strategy provides advice to jurisdictions and organizations that may be involved or wish to become involved in the recovery of the species. In the spirit of the National Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans invites all responsible jurisdictions and Canadians to join Fisheries and Oceans Canada in supporting and implementing this strategy for the benefit of the Northern Madtom and Canadian society as a whole. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will support implementation of this strategy to the extent possible, given available resources and its overall responsibility for species at risk conservation.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best existing knowledge and are subject to modifications resulting from new information. The Minister of Fisheries and Oceans will report on progress within five years.

This strategy will be complemented by one or more action plans that will provide details on specific recovery measures to be taken to support conservation of the species. The Minister of Fisheries and Oceans will take steps to ensure that, to the extent possible, Canadians interested in or affected by these measures will be consulted.

Under the Species at Risk Act, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) is the responsible jurisdiction for the Northern Madtom. The province of Ontario also cooperated in the production of this recovery strategy.

This document was prepared by Amy L. Edwards (DFO), André Y. Laurin (DFO Contractor) and Shawn K. Staton (DFO) on behalf of Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada would like to thank the following organizations for their support of the Ontario Freshwater Fish Recovery Team in the development of the Northern Madtom recovery strategy: Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Essex Region Conservation Authority, Trent University and Upper Thames River Conservation Authority. Mapping was produced by Carolyn Bakelaar (GIS Analyst - DFO).

In accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals, the purpose of a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is to incorporate environmental considerations into the development of public policies, plans, and program proposals to support environmentally-sound decision making.

Recovery planning is intended to benefit species at risk and biodiversity in general. However, it is recognized that strategies may also inadvertently lead to environmental effects beyond the intended benefits. The planning process based on national guidelines directly incorporates consideration of all environmental effects, with a particular focus on possible impacts on non-target species or habitats.

This recovery strategy will clearly benefit the environment by promoting the recovery of the Northern Madtom. The potential for the strategy to inadvertently lead to adverse effects on other species was considered. The SEA concluded that this strategy will clearly benefit the environment and will not entail any significant adverse effects. Refer to the following sections of the document, in particular: Description of the Species’ Habitat and Biological Needs, Ecological Role, and Limiting Factors; Effects on Other Species; and the Recommended Approaches for Recovery.

SARA defines residence as: “a dwelling-place, such as a den, nest or other similar area or place, that is occupied or habitually occupied by one or more individuals during all or part of their life cycles, including breeding, rearing, staging, wintering, feeding orhibernating”

[SARA S2(1)].

Residence descriptions, or the rationale for why the residence concept does not apply to a given species, are posted on the SARA public registry.

The Northern Madtom is a small (132 mm, maximum total length) freshwater catfish recognized by an overall mottled colour pattern with three distinct saddle-shaped markings on the back, located at the front of the dorsal fin, behind the dorsal fin and at the adipose fin. Evidence suggests that the Northern Madtom tolerates a wide range of habitat conditions and can be found in small creeks to large rivers, with clear to turbid water and moderate to swift current over substrates consisting of sand, gravel and rocks, occasionally with silt, detritus and accumulated debris. It is also occasionally associated with macrophytes such as stonewort. The Northern Madtom is native to North America and has a disjunct distribution throughout parts of the Mississippi and western Lake Erie and Lake St. Clair drainages. This species is considered to be rare to extremely rare throughout its range and has a global status rank of G3 (vulnerable); a national status rank of N3 (vulnerable) in the United States; and, a Canadian national status of N1N2 (critically imperilled/imperilled). There are two, possibly three, extant, reproducing populations in Canada: 1. lower Lake St. Clair – Detroit River; 2. Thames River of southwestern Ontario; and, 3. potentially the St. Clair River (a juvenile was caught in 2003, suggesting that reproduction may be occurring). A single specimen was collected from the Sydenham River in 1975; however, this remains the only record of Northern Madtom for this location.

The potential threats identified for the Northern Madtom include: siltation, turbidity, nutrient loading, physical habitat loss, toxic compounds, exotic species and climate change. Further investigation on the impacts and effects of these threats on the Northern Madtom is required to inform successful recovery efforts.

This recovery strategy was prepared by members of the Ontario Freshwater Fish Recovery Team and is based, in part, on content from existing ecosystem-based recovery strategies.

The long-term recovery goal (greater than 20 years) is to sustain and enhance the viability of existing populations of Northern Madtom in the Erie-Huron corridor, the Thames River (from Littlejohn Rd. upstream to vicinity of Tate Corners), and the Sydenham River if the species is still present in the system.

The following short-term objectives (5-10 years) have been established to assist with meeting the long-term recovery goal:

- Refine population and distribution objectives;

- Ensure the protection of critical habitat;

- Determine long-term population and habitat trends;

- Evaluate and mitigate threats to the species and its habitat;

- Determine the feasibility of relocations and captive rearing;

- Ensure efficient use of resources (human and fiscal) during recovery planning efforts; and,

- Improve awareness of the Northern Madtom and engage the public in the conservation of the species.

The recovery team has identified several approaches necessary to ensure that recovery objectives for the Northern Madtom are met. These approaches have been organized into three categories: 1. Research and Monitoring; 2. Management and Coordination; and, 3. Stewardship, Outreach and Awareness. Implementation of these approaches will be accomplished in coordination with relevant ecosystem-based recovery teams and associated implementation groups.

Using available data, critical habitat has been identified at this time for Northern Madtom populations in the Detroit River and the lower Thames River; additional areas of potential critical habitat within Lake St. Clair will be considered in collaboration with Walpole Island First Nation. Currently, there is insufficient information to identify critical habitat in the St. Clair River. A schedule of studies has been developed that outlines necessary steps to obtain the information to identify critical habitat in the St. Clair River, and to further refine current critical habitat descriptions in the Detroit River and the Thames River. Until critical habitat has been fully identified, the recovery team recommends that currently occupied habitats are habitats in need of conservation.

The recovery team recommends a dual approach to recovery implementation which combines an multi-species, ecosystem-based approach complemented by a single-species approach. The team will accomplish this by working closely with existing ecosystem recovery teams and other relevant organizations to combine efficiencies and share knowledge on recovery initiatives. The recovery strategy will be supported by one or more action plans that will be developed within five years of the final recovery strategy being posted to the public registry. The success of recovery actions will be evaluated through the performance measures provided. The entire recovery strategy will be reported on every five years to evaluate progress and incorporate new information.

Common Name: Northern Madtom

Scientific Name: Noturus stigmosus

Current COSEWIC Status & Year of Designation: Endangered (2002)

Reason for Designation: This species has a very restricted Canadian range (two extant locations), which is impacted by deterioration in water quality and potential negative interactions with an exotic species, the Round Goby (Neogobius melanostomus). One population (Sydenham River) has been lost since 1975.

Canadian Occurrence: Ontario

COSEWIC Status History: Examined in April 1993 and placed in the Data Deficient category. Re-examined in April 1998 and designated Special Concern. Status re-examined and uplisted to Endangered in November 2002. Last assessment was based on an existing status report with an addendum.

The following description is adapted from Holm and Mandrak (1998). The Northern Madtom (Noturus stigmosus Taylor, 1969) is a small (132 mm, maximum total length) catfish (Ictaluridae) recognized by an overall mottled colour pattern with three distinct saddle-shaped markings on the back, located at the front of the dorsal fin, behind the dorsal fin and at the adipose fin (Figure 1). Two pale spots that are smaller than the diameter of the eye are usually present anterior to the dorsal fin. The dorsal and adipose fins possess pale edges while three to four irregular crescent-shaped bars are present on the caudal fin, with the middle bar typically extending across the upper and lower caudal rays and touching the caudal peduncle. Reproductive males will develop a flattened head, diffusion of dark pigments and conspicuous swellings behind the eyes, on the nape and on the lips and cheeks. The Northern Madtom is most often confused with the Brindled Madtom (N. miurus), which lacks pale edges on the dorsal and adipose fins, has a black tip on the dorsal fin, and has a shallower notch between the adipose fin and the tail (Holm et al. 2009).

No subspecies of Northern Madtom have been recognized (Holm and Mandrak 1998); however, Mayden et al. (1992; cited in Holm and Mandrak 1998) suggested that it might be polytypic which may warrant its separation into several species. The Northern Madtom underwent a taxonomic revision and a new species (N. gladiator) was described from populations of the Coastal Plain in Kentucky and Tennessee (Thomas and Burr 2004). In a study examining the phylogenetic relationships among Noturus spp., Hardman (2004) compared nucleotide sequences from Northern Madtom populations above and below (now considered to be N. gladiator [Thomas and Burr 2004]) the Fall Line (a low east-facing cliff that parallels the Atlantic coastline from New Jersey to the Carolinas) and found them to be genetically less than 1% different, despite being morphologically differentiable. It is important to note that Canadian specimens were not included in these taxonomic studies.

Figure 1. The Northern Madtom (Noturus stigmosus). © 1996 Joseph R. Tomelleri.

Long description of Figure 1

The Northern Madtom is native to North America and has a disjunct distribution throughout parts of the Mississippi and western Lake Erie and Lake St. Clair drainages (Figure 2). It is found in several tributaries of the Mississippi drainage system in Tennessee. It is also present throughout most of the Ohio River basin in Indiana, Kentucky and Ohio, as well as in restricted areas of Illinois, Pennsylvania and West Virginia. In the western basin of Lake Erie, the Northern Madtom is found in several tributaries in Indiana, Michigan and Ohio, as well as in Lake St. Clair and the Detroit and St. Clair rivers, which form the border between Michigan and Ontario (Holm and Mandrak 2001).

Figure 2. Global range of the Northern Madtom.

Long description of Figure 2

In Canada, the Northern Madtom is known only from Lake St. Clair and the Detroit, St. Clair, Sydenham and Thames rivers (Figure 3). The species is believed to be extirpated from the Sydenham River (Holm and Mandrak 1998).

It is likely that less than 5% of the species global range occurs in Canada.

The change in the distribution of the Northern Madtom is difficult to assess due to a lack of sampling data. It is unclear whether new records of the species (since it was first reported in Canada in 1963) are a result of a range expansion or more intensive sampling (Holm and Mandrak 1998).

Figure 3. Canadian range of the Northern Madtom.

Long description of Figure 3

The Northern Madtom is considered to be rare to extremely rare throughout its range (Table 1) and has a global status rank of vulnerable (NatureServe 2009). The species is considered critically imperilled in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio and West Virginia. In Pennsylvania and Kentucky the Northern Madtom is considered imperilled and imperilled/vulnerable, respectively. It has not been assigned a rank in Arkansas (NatureServe 2009). The global short-term trend of Northern Madtom populations is estimated as declining to stable (± 10% fluctuation to 30% decline) (NatureServe 2009).

| Canada and U.S. National Rank (NX) | Provincial/State Rank (SX) |

|---|---|

| Canada (N1N2) | Ontario (S1) |

| United States (N3) | Arkansas (SNR), Illinois (S1), Indiana (S1), Kentucky (S2S3), Michigan (S1), Ohio (S1), Pennsylvania (S2), West Virginia (S1) |

In Canada, the Northern Madtom occurs within an area less than 1600 km² and occupies an area less than 700 km² (COSEWIC 2002); however, this does not include the recently confirmed St. Clair River record.

Lake St. Clair, Detroit River, St. Clair River

The first recorded occurrence of the Northern Madtom in Canada was a single specimen that was trawled from Lake St. Clair, near the outlet into the Detroit River, in 1963 (Trautman 1981). Although it was not recorded from Canada until 1963, it is likely that Northern Madtom has always been present but went undetected because it is a cryptic species. Additionally, the species is found in areas that are difficult to sample as a result of accessibility issues and the nature of the habitat (e.g., swift-flowing, deep, waters). In 1996, three juveniles were seined at night along the south shore of Lake St. Clair at the mouth of the Belle River (Holm and Mandrak 2001) and a single individual was found dead near the mouth of Pike Creek (Royal Ontario Museum [ROM], unpubl. data). The most recent Canadian record for Northern Madtom in Lake St. Clair is from 1999 when one specimen was captured incidentally by a commercial fisherman off of Walpole Island.

In 1994, a single Northern Madtom was caught near the original capture site on the Canadian side of the Detroit River (Holm and Mandrak 1998) and in 1996 approximately 50 specimens were either observed or collected around Peche Island in the Detroit River. In 2008, a total of 214 Northern Madtom were captured in the Detroit River during a mark-recapture study conducted by a graduate student with the United States Geological Survey (USGS); 145 specimens were captured on the American side of the river adjacent to Belle Isle and 69 specimens, including four young-of-the-year (YOY), were captured on several occasions (from one site) on the Canadian side near Peche Island (B. Daley, USGS, unpubl.data). One individual originally captured and marked at Belle Isle was recaptured almost a mile upstream near Peche Island (B. Daley, unpubl. data).

Preliminary results of sampling conducted at Fighting Island in 2009 indicate that Northern Madtom is present at this location, which is approximately 20 kilometres downstream of Peche Island. Seven specimens (102-126 mm TL) were captured in minnow traps at artificial spawning shoals created for Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) (United States Fish and Wildlife Service [USFWS], unpubl. data). Holm and Mandrak (2001) suggested that the lack of Canadian records in the Detroit River and Lake St. Clair between 1963 and 1994 probably resulted from the limited amount of trawling and night sampling conducted, as well as errors in species identification.

Sampling (day and night trawls, and day and night seining) by the ROM in 1996 failed to capture or observe the Northern Madtom on the Canadian side of the St. Clair River; however, sampling conducted by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) in 2003 yielded a juvenile (suggesting successful reproduction) downstream of the Lambton Generating Station at the confluence of Clay Creek. Northern Madtom records exist for the American side of the St. Clair River; it was last recorded in 1995, when several larvae, YOY and adult specimens were captured (Carman 2001).

Thames River and Sydenham River

In July 1991, a specimen was captured by the ROM in the Thames River near Wardsville, and a juvenile Northern Madtom was captured at the same location in August 1997 (Holm and Mandrak 2001). From 2003 to 2008, juvenile and adult Northern Madtom were captured incidentally by graduate students conducting research on the Eastern Sand Darter (Ammocrypta pellucida). The majority of specimens were captured in the vicinity of Big Bend Conservation Area, located upstream of Wardsville. Targeted sampling for the Northern Madtom conducted in 2008 by DFO failed to capture any specimens; however, the species was captured incidentally in 2008 near Big Bend (A. Dextrase, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR), pers. comm. 2009).

A specimen originally identified as a Brindled Madtom caught in 1975 in the Sydenham River near Florence, was re-examined by the ROM in 1999 and identified as a Northern Madtom. Although it is possible that this specimen was the result of an introduction (e.g., bait-bucket release), it is more likely representative of an established population in the Sydenham River due to the proximity of other confirmed records within the Lake St. Clair watershed (i.e., Thames River and Lake St. Clair). No specimens have been recorded from the Sydenham River since 1975, despite repeated sampling in the same locale (Holm and Mandrak 1998); thus, it is likely that if there was an established population in the river, it is now extirpated.

The percentage of the species’ global abundance in Canada is unknown; however, it is likely to be less than 5%.

The presence of juveniles in Lake St. Clair, the Detroit River, the St. Clair River and the Thames River, indicates that reproduction is presently occurring; however, the lack of short- and long-term population abundance and demographic data in Canada greatly limits our ability to properly assess population trends and stability.

Spawn to Hatch

Northern Madtom are cavity nesters, building nests in depressions under large rocks and in debris such as bottles, cans and boxes (Etnier and Starnes 1993, Goodchild 1993, Holm and Mandrak 1998, MacInnis 1998). Taylor (1969) observed that, in Michigan, the Northern Madtom reproduced earlier than the Brindled Madtom, and that clutch sizes were larger, ranging from 61 to 141 eggs. In Michigan, spawning occurs in mid- to late-July, similar to a population in the Canadian portion of Lake St. Clair (MacInnis 1998). Northern Madtom were observed and video recorded by MacInnis (1998) at one site (near Sandpoint Beach, close to the outflow into the Detroit River) in Lake St. Clair between 17 July and 13 August 1996, while conducting a study on Round Goby (Neogobius melanostomus) reproduction using artificial nest cavities. During this time, gravid Northern Madtom and recently spawned eggs were observed in the artificial cavities, and male Northern Madtom were observed guarding both eggs and newly hatched larvae. MacInnis (1998) concluded that reproduction in the Northern Madtom likely occurred over a one-month period and that males provided sole parental care of eggs, larvae and juveniles. Nests consisted of a small depression dug into the substrate under the artificial cavity and eggs were laid as a single mass. Fecundity was conservatively estimated as 32, 85 and 140 eggs for three separate egg masses (MacInnis 1998), a relatively low number; as a group, madtoms are one of the least fecund oviparous fishes in North America (Burr and Stoeckel 1999). MacInnis (1998) also proposed that the larger egg masses represented the spawning efforts of more than one female; however, this was not directly observed. Incubation time was estimated at five to ten days and YOY were measured at approximately 30 mm TL before their first winter (MacInnis 1998). The spawning sites in Lake St. Clair had substrates of sand and/or cobble and were surrounded by dense aquatic vegetation. Water depths ranged from 1.5 to 1.8 m, water temperature was approximately 23°C and there was a noticeable current flowing west into the Detroit River (MacInnis 1998). There is no information regarding the spawning habitat characteristics for the Northern Madtom in the Thames River.

Young-of-the-Year (YOY)

There is almost no published information on the habitat requirements of YOY Northern Madtom. In Lake St. Clair, larvae were observed in nests being guarded by the male in August and were observed taking cover in surrounding vegetation when the nests were removed (MacInnis 1998); therefore, it is likely that they require some sort of structure to provide cover. In the Thames River, YOY have been captured from shallow (< 2 m) sandbars that had little flow (M. Finch, University of Waterloo, unpubl. data) as well as areas containing substrates of fine gravel (mean size 2-8 mm) and moderate flow (0.3 m/s) (A. Dextrase, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources [OMNR], unpubl. data). The YOY of two related species, the Brindled Madtom and Tadpole Madtom (N. gyrinus), are typically found in shallow waters (0-2 m) over substrates of sand, mud and silt, with aquatic vegetation (Goodyear et al. 1982, Lane et al. 1996b).

Juvenile (age 1 until sexual maturity [2 yrs])

The habitat requirements of juvenile Northern Madtom are unknown; however, a juvenile specimen was collected from the same site as an adult specimen in the Thames River (Holm and Mandrak 1998), suggesting that adult and juvenile habitat requirements are the same or similar.

Adult

Goodchild (1993) noted that small and sporadic populations suggest that the Northern Madtom has very specific ecological requirements and thus is probably intolerant of habitat degradation. However, more recent evidence suggests that the species tolerates a wide range of habitat conditions (Dextrase et al. 2003). It can be found in small creeks to large rivers, with clear to turbid water and moderate to swift current over substrates consisting of sand, gravel and rocks, occasionally with silt, detritus and accumulated debris. Although the species is somewhat tolerant of turbidity, it is believed to avoid extremely silty situations (Goodchild 1993). It is also occasionally associated with macrophytes, such as stonewort (Chara spp.) (Holm and Mandrak 2001). The Northern Madtom has been sampled at depths ranging from less than 1 m to 7 m, where it was either seined or trawled during the day and/or night. For example, two specimens were collected in the Thames River, which is very turbid (Secchi depth < 0.2 m), over a substrate consisting of sand, gravel and rubble, and devoid of silt or clay (Holm and Mandrak 2001). Other abiotic characteristics of the site also included a moderate current, maximum depth of 1.2 m, water temperature of 23-26°C, conductivity of 666 μS and a pH of 7.9 (Holm and Mandrak 2001). Sexual maturity in the Northern Madtom is believed to be reached at approximately two years of age (Taylor 1969).

The Northern Madtom is likely an opportunistic feeder with a diet consisting mainly of chironomids, mayflies, caddisflies, small fishes and crustaceans (Holm and Mandrak 2001). A gut analysis study by French and Jude (2001) found the gut contents of juvenile Northern Madtom to consist mostly of Diptera and Ephemeroptera. The Northern Madtom is very secretive and likely to be a nocturnal feeder (Goodchild 1993) and spawner (Coad 1995).

The Northern Madtom is a nocturnal, benthic feeder, and gut contents demonstrate its reliance on small benthic invertebrates, such as chironomids, mayflies and caddisflies, as well as small fishes and crustaceans. Other benthic fishes, such as other madtoms (Noturus spp.), gobies (Round Goby, Tubenose Goby [Proterorhinus marmoratus]) and sculpins (Cottus spp.), may directly compete with the Northern Madtom for these food sources.

The Northern Madtom may be limited by several life-history traits which include: minimal temperature for spawning; spawning habitat requirements; and, fecundity and maximum age. Populations of Northern Madtom in Canada appear to be at the northern edge of the species’ distribution, which is limited by an estimated minimal spawning temperature of 23°C (Taylor 1969, MacInnis 1998). The Northern Madtom is a cavity spawner, thus the availability of suitable spawning habitat (silt-free cavities in substrate or under debris/rocks/logs) may also pose a limitation to the species. Competition for suitable spawning sites is likely to occur with the Brindled Madtom and potentially with the Round Goby; however, direct competition has yet to be documented (MacInnis 1998, Holm and Mandrak 2001). Although strong parental care (via nest-guarding) is provided by the male Northern Madtom, there is limited knowledge of the species’ ability to compete for nest sites. Additional research is needed to clarify the role of interspecific competition on reproductive success. The Northern Madtom is a relatively short-lived species, with a maximum reported age of approximately two to three years (Taylor 1969) and likely spawns only once or twice in its lifetime (inferred from Burr and Stoeckel 1999). However, it should be noted that populations of many fishes at the northern limit of their range typically have longer life spans – this may also be the case for the Northern Madtom in Canada. As suggested by Simonson and Neves (1992), relying on only one or two cohorts for reproduction each year could jeopardize the long-term stability of some small madtom populations. This, combined with the low fecundity of the Northern Madtom, may limit the population potential of the species.

The threats identified for the Northern Madtom are considered to be potential threats as they have not been demonstrated empirically. Thus, the following discussion is based primarily on assumption and/or plausible cause.

Threats believed to be affecting the Northern Madtom are listed by waterbody in Table 2. Seven potential threats were ranked by the recovery team based on their expected relative impacts, spatial extent and expected severity. The threat classification parameters are defined as follows:

| Population | Specific threat | Extent (widespread/localized) | Frequency (seasonal/continuous) | Causal certainty (high, medium, low) |

Severity (high, medium, low) |

Overall level of concern (high, medium, low) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thames River | Siltation | Widespread | Continuous | Medium | High | High |

| Thames River | Turbidity | Widespread | Continuous | Low | High | High |

| Thames River | Nutrient loadings | Widespread | Continuous | Medium | High/Medium | High |

| Thames River | Exotic species | Localized | Unknown | Medium | Low (increasing) | High |

| Thames River | Toxic compounds (pesticides/herbicides) | Localized | Seasonal | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Thames River | Physical habitat loss | Localized | Continuous | Medium | Extremely Low | Extremely Low |

| Detroit River/Lake St. Clair | Siltation | Localized | Continuous | Medium | Low/Medium | Medium |

| Detroit River/Lake St. Clair | Turbidity | Widespread | Continuous | Low | Low | Low |

| Detroit River/Lake St. Clair | Nutrient loadings | Widespread | Continuous | Medium | Medium/High | Medium? |

| Detroit River/Lake St. Clair | Exotic species | Widespread | Continuous | Medium | High | High |

| Detroit River/Lake St. Clair | Toxic compounds | Detroit River - Widespread; Lake St. Clair – Localized | Continuous | Medium | High | High |

| Detroit River/Lake St. Clair | Physical habitat loss | Localized | Continuous | Medium | High | High |

| St. Clair River | Siltation | Localized | Continuous | Medium | Low/Medium | Medium |

| St. Clair River | Turbidity | Widespread | Continuous | Low | Low | Low |

| St. Clair River | Nutrient loadings | Widespread | Continuous | Medium | Medium/High | Medium? |

| St. Clair River | Exotic species | Widespread | Continuous | Medium | High | High |

| St. Clair River | Toxic compounds | Widespread | Continuous | Medium | High | High |

| St. Clair River | Physical habitat loss | Localized | Continuous | Medium | High | High |

| All populations | Climate change | Widespread | Continuous | High | Low | Low |

Siltation and turbidity

An increase in suspended sediments leads to increased turbidity, decreased light penetration and lower primary productivity. High rates of sediment deposition can alter the composition of gravel and cobble habitats, thus impacting the quality and availability of fish habitat (Bailey and Yates 2003). The impacts of high sediment loading on the Northern Madtom are not fully understood. The species has been collected from highly turbid waters, such as the Thames River, suggesting that the species has some level of tolerance to turbidity. However, the Northern Madtom is no longer found in the turbid Sydenham River, which is located in an intensive agricultural landscape (Holm and Mandrak 1998) (assuming there was a population in the Sydenham River). It is unclear whether the Northern Madtom is primarily impacted by suspended sediments in the water column or excessive sediment deposition on the substrate; however, it seems likely that high rates of silt deposition could affect the species ability to nest in cavities (Dextrase et al. 2003, The Thames River Recovery Team [TRRT] 2005). Silt deposition may also indirectly impact the Northern Madtom through a potential reduction in their invertebrate food supply.

Direct soil deposits through agricultural tile drainage systems and overland runoff have the greatest influence on siltation rates (Bailey and Yates 2003). Furthermore, channelization and loss of riparian zones along lakes and watercourses increases the level of sediment input, as well as the rate of streambank and shoreline erosion. Livestock grazing and ploughing to the edge of a watercourse destroys riparian vegetation, thus impacting rates of silt deposition into adjacent watercourse (Bailey and Yates 2003). In the United States, channelization is the most serious threat facing the Northern Madtom, followed closely by increased siltation and turbidity (NatureServe 2009).

Nutrient loading

Increased nutrient loading can have an impact on water quality and may have direct and indirect effects on the Northern Madtom. Nutrient loading, especially of phosphorus and nitrogen, from agricultural fertilization and manure use practices, as well as effluents from sewage treatment plants and faulty septic systems, can adversely affect habitat quality. Such negative impacts may include increased turbidity, increased occurrence of harmful algal blooms, disruption of food webs and increased macrophyte growth (Bailey and Yates 2003). In the Thames River, phosphorous levels at most sites in the watershed have shown a gradual downward trend since the 1970s; however, levels remain above provincial guidelines of 30 µg/L for the protection of aquatic life (The Thames River Ecosystem Recovery Team [TRERT] 2004). From the period covering 2001-2006, the median total phosphorous concentration in the Thames River was 113 µg/L, second only to the Don River in Ontario for total phosphorous levels (Ontario Ministry of the Environment 2009). Additionally, mean nitrite/nitrate values in the Thames River watershed were over the recommended limits from 1991-2000, and nitrate levels have shown an increasing trend in the watershed over the past 30 years (TRERT2004).

Physical habitat loss

Physical habitat loss is one of the leading threats to aquatic species at risk (Dextrase and Mandrak 2006), and this is likely the case for the Northern Madtom. Habitat loss from dredging, as well as lake and river shoreline modifications (e.g., shoreline hardening projects, piers, docks, marinas) along the Detroit River and Lake St. Clair, is a significant and ongoing concern.

Toxic compounds

The effects of toxic compounds on the Northern Madtom are currently unknown. The species is found in the Detroit and St. Clair Rivers which have both been designated as an Area of Concern (AOC). An AOC is a severely degraded geographic area within the Great Lakes Basin with known impairments of beneficial water use that can impact the area’s ability to support aquatic life (Great Lakes Information Network 2009). Beneficial use impairments have been identified in the St. Clair River (10 impairments) and the Detroit River (11) as a result of urban and industrial development, bacteria, PCBs, PAHs, metals, oils and greases (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 2009). In the Thames River, pollutants may include pesticides from agricultural and urban areas, chloride (e.g., from road salt, wastewater treatment and water softeners) and metals (TRERT 2004). Over the past 30 years, chloride levels in the Thames River have increased continually at sites across the watershed, but in most cases remain below the Environment Canada guidelines for sensitive aquatic species (TRERT 2004). In the United States, chemical run-off from agricultural and urban sources is one of the major threats facing Northern Madtom (NatureServe 2009). A related species, the Neosho Madtom (N. placidus), appears to be limited by the presence of heavy metals such as cadmium, lead and zinc (Wildhaber et al. 2000).

Further investigation is required to identify the impacts of pollutants and to fully understand the type and extent of stress exerted upon Northern Madtom populations in Canada.

Exotic species

The negative impacts of exotic species on native fishes in the Great Lakes basin have been well documented (e.g., French and Jude 2001, Thomas and Haas 2004). Exotic species may affect the Northern Madtom through direct competition for space and habitat, food, spawning sites and through the restructuring of aquatic food webs. The occurrence of the Round Goby has been implicated in the decline of the Mottled Sculpin (Cottus bairdii) and the Logperch (Percina caprodes) in the St. Clair River (French and Jude 2001). Given the ecology of the Round Goby, it could, potentially, directly compete with the Northern Madtom for food and habitat (MacInnis 1998, Jansen and Jude 2001). The Round Goby could also directly compete with Northern Madtom for spawning sites; however, the Northern Madtom would likely not be as vulnerable to competition for spawning sites as the spawning seasons of the two species barely overlap (MacInnis and Corkum 2000). Although the Round Goby has been found in the lower reaches of the Sydenham and Thames rivers, recent sampling on both rivers has documented considerable upstream movement in 2007 to areas where it had not previously been found (A. Dextrase, pers. comm., 2007, M. Poos, University of Toronto, pers. comm., 2007). In the Sydenham River, the Round Goby has been confirmed in the mid-reaches, just 3 km downstream from the town of Florence. The impacts of the exotic Zebra Mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) and Quagga Mussel (D. bugensis) on the Northern Madtom are unknown but may negatively impact the species by colonizing potential nesting cavities as well as altering food web dynamics and surrounding water quality.

Further research on the impacts of exotic species including Zebra and Quagga mussels, on the Northern Madtom in the Detroit River – St. Clair River corridor, as well as in the Sydenham and Thames rivers is required to provide recovery planners with better tools to manage and understand the Northern Madtom within these systems.

Climate change

Climate change is expected to impact the Northern Madtom and other fishes at risk in southwestern Ontario (Essex-Erie Recovery Team [EERT] 2008). Several impacts related to climate change are expected to impact aquatic communities of the Great Lakes basin, including: increases in water and air temperatures; changes in water levels; shortening of the duration of ice cover; increases in the frequency of extreme weather events; emergence of diseases; and, shifts in predator-prey dynamics (Lemmen and Warren 2004). The effects of climate change will be widespread and should be considered a contributing impact to species at risk and all habitats. While it is possible that some species, including the Northern Madtom, may benefit initially from the effects of climate change through possible northern range expansions, a suite of reactions related to expected changes in evaporation patterns, vegetation communities, decreased lake levels, increased intensity and frequency of storms, and decreases in summer stream water levels may offset the direct benefits of increased water temperatures (EERT 2008).

Ecosystem recovery strategies: The following aquatic ecosystem-based recovery strategies include the Northern Madtom and are currently being implemented by their respective recovery teams. Each recovery team is co-chaired by DFO and a Conservation Authority and receives support from a diverse partnership of agencies and individuals. Recovery activities implemented by these teams include active stewardship and outreach/awareness programs to reduce identified threats; for further details on specific actions currently underway, please refer to the approaches identified in Table 6. Funding for these actions is supported by Ontario’s Species at Risk Stewardship Fund and the government of Canada’s Habitat Stewardship Program for Species at Risk. Additionally, research requirements for species at risk identified in recovery strategies are funded, in part, by the federal Interdepartmental Recovery Fund.

Essex-Erie Region Fishes - The Essex-Erie region is located on the north shore of Lake Erie and is bordered to the east by the Grand River watershed, to the west by the Detroit River and to the north by the Lake St. Clair and Thames River watershed. The long-term goal of this strategy is “to maintain and restore ecosystem quality and function in the Essex-Erie region to support viable populations of fish species at risk, across their current and former range” (EERT 2008).

SydenhamRiver Ecosystem - The long-term goal of this strategy is “to sustain and enhance the native aquatic communities of the Sydenham River through an ecosystem approach that focuses on species at risk” (Dextrase et al.2003).

ThamesRiver Ecosystem - The goal of this strategy is to develop “a recovery plan that improves the status of all aquatic species at risk in the Thames River through an ecosystem approach that sustains and enhances all native aquatic communities” (TRRT 2005).

WalpoleIsland Ecosystem Recovery Strategy: The Walpole Island ecosystem recovery team was established in 2001 to develop an ecosystem-based recovery strategy for the area containing the St. Clair delta, the largest freshwater delta in the world, with the goal of outlining steps to be taken to maintain or rehabilitate the ecosystem and species at risk (Bowles 2005). This recovery strategy includes several fishes at risk, including the Northern Madtom. The recovery goal of the Walpole Island ecosystem recovery strategy is “to conserve and recover the ecosystems of the Walpole Island Territory in a way that is compliant with the Walpole Island First Nation Environmental Philosophy Statement, provides opportunities for cultural and economic development and provides protection and recovery for Canada’s species at risk” (Bowles 2005).

Remedial action plans (RAPs): RAPs have been developed for the Detroit River AOC and the St. Clair River AOC to guide restoration and protection efforts. RAPs proceed through three stages: 1) Determination of severity and causes of environmental degradation; 2) Identification of goals, recommendation of actions that will lead to protection and restoration of ecosystem health; and, 3) Implementation of recommended actions and progress towards restoration and protection efforts measured (Environment Canada 2008a). There are 45 and 104 recommended remedial actions for the St. Clair River AOC and Detroit River AOC, respectively, and many of these have already been implemented (Environment Canada 2008b,c).

Recent surveys: Table 3 summarizes recent fish surveys conducted by various agencies within areas of known occurrence of the Northern Madtom.

| Waterbody / general area | Survey description (years of survey) | Gear type | Northern Madtom captured (Yes/No) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lake St. Clair | OMNR nearshore fish community survey (2005 and 2007-2010; south shore) | seine |

No

|

| Lake St. Clair | OMNR nearshore fish community survey (2007; south shore) | boat electrofishing |

No

|

| Lake St. Clair | Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR) fish community survey (1996-2001; south shore) | trawl |

No

|

| Lake St. Clair | DFO sampling (2003, 2004; St. Clair NWA) | boat electrofishing |

No

|

| Lake St. Clair | ROM (2001-2002; Walpole Island) |

No

|

|

| Lake St. Clair | DFO/University of Guelph sampling (2003-2004; Mitchell’s Bay) | boat electrofishing, additional gear (fyke nets, trap nets, minnow traps etc) |

No

|

| Detroit River | DFO/University of Windsor fish-habitat association study (2003-2004) | seine, boat electrofishing |

No

|

| Detroit River | DFO/University of Guelph coastal wetlands study (2004-2005) |

No

|

|

| Detroit River | DFO Area of Concern sampling (2003-2004) |

No

|

|

| Detroit River | Michigan DNR/USFWS/OMNR nearshore fish community sampling (2008) | seine, boat electrofishing,additional gear (fyke nets, trap nets, minnow traps etc) |

No

|

| Detroit River | USGS Northern Madtom sampling (2008) | additional gear (fyke nets, trap nets, minnow traps etc) |

Yes

|

| Detroit River | USFWS sampling (2009) | additional gear (fyke nets, trap nets, minnow traps etc) |

Yes

|

| St. Clair River | DFO fish community sampling (2003, 2004) |

Yes

|

|

| St. Clair River | DFO/University of Guelph fish community sampling (2007) | boat electrofishing |

No

|

| Thames River | UTRCA fish SAR survey and gear comparison study 2003 and 2004, upper Thames River | seine, trawl, backpack electrofishing, boat electrofishing, additional gear (fyke nets, trap nets, minnow traps etc) |

No

|

| Thames River | DFO/UTRCA fish SAR survey and gear comparison study 2003 and 2004, lower Thames River and lower Thames tributaries | seine, trawl, backpack electrofishing, boat electrofishing, additional gear (fyke nets, trap nets, minnow traps etc) |

Yes

|

| Thames River | DFO/University of Waterloo lower Thames River Eastern Sand Darter sampling (2006, 2007) | seine |

Yes

|

| Thames River | DFO/OMNR/Trent University lower Thames River Eastern Sand Darter sampling (2006-2008) | seine |

Yes

|

| Thames River | DFO targeted Northern Madtom gear comparison survey (2008) | seine, trawl, additional gear (fyke nets, trap nets, minnow traps etc) |

No

|

| Sydenham River | ROM non-targeted species at risk sampling (1997) | seine |

No

|

| Sydenham River | DFO/University of Guelph (2002-2003) (including night seining at Florence [historic site]) | seine, backpack electrofishing |

No

|

In Canada, the Northern Madtom has not been thoroughly studied, and, given its rarity and secretive, nocturnal habits, there are numerous aspects regarding its biology, population structure, ecology and life-history traits that remain unknown. This information is required to refine recovery approaches. It is unclear whether a population ever existed in the Sydenham River or whether the single specimen collected was the result of an accidental (bait-bucket or other) introduction. Threat clarification is required, particularly concerning siltation and the impacts of the Round Goby and Zebra Mussel.

The following goals, objectives and recovery approaches were adapted from the Essex-Erie Recovery Strategy (EERT 2008) which covers a portion of the Canadian range of the Northern Madtom. Additional considerations were included from the Sydenham River Recovery Strategy (Dextrase et al. 2003) and Thames River Recovery Strategy (TRRT 2005).

The recovery of the Northern Madtom is believed to be biologically and technically feasible. The following feasibility criteriaFootnote1 have been met for the species:

- Are individuals capable of reproduction currently available to improve the population growth or population abundance?

Yes. Reproducing populations are believed to exist within the Canadian range of the Northern Madtom (i.e., lower Lake St. Clair, the Detroit River, the Thames River and potentially the St. Clair River).

- Is sufficient habitat available to support the species or could it be made available through habitat management or restoration?

Yes. Sufficient habitat is present at locations with extant populations. At locations with extirpated populations, suitable habitat may be made available through recovery actions.

- Can specific threats to the species or its habitats be avoided or mitigated through recovery actions?

Yes. The impacts/effects of suspected threats, such as sediment and nutrient loading, can be mitigated through established restoration methods.

- Do the necessary recovery techniques exist and are they demonstrated to be effective?

Yes. Recovery techniques to reduce sediment and nutrient loading (e.g., stewardship, Best Management Practices [BMPs]) are well established and proven to be effective.

Captive rearing and translocations have been used in the western and southeastern United States towards recovery of endangered fishes, including non-game benthic species (e.g., Andreasen and Springer 2000, Shute et al. 2005). Although there are no published studies on the husbandry of Northern Madtom, captive rearing and translocations of the closely related Smoky Madtom (N. baileyi) and Yellowfin Madtom (N. flavipinnis) have been successfully accomplished in Abrams Creek, Tennessee (Shute et al. 2005).

The Northern Madtom is a naturally rare component of the fish community throughout its range in Canada. The level of effort required for recovery of this species would likely be moderate for the Detroit River, Lake St. Clair, St. Clair River and Thames River given that these populations are currently believed to be reproducing. The level of effort required for recovery is unknown for the Sydenham River population given the uncertainty surrounding the population status.

The long-term recovery goal (greater than 20 years) is to sustain and enhance the viability of existing populations of Northern Madtom in the Erie-Huron corridor, the Thames River (the reach of river from Littlejohn Rd. upstream to an area near Tate Corners) and the Sydenham River, if the species is still present in the system.

Population and distribution objectives for the Northern Madtom over the next five years are to maintain distributions of extant populations in Lake St. Clair, the Detroit River, the St. Clair River and the Thames River. Quantifiable objectives relating to individual populations are not currently possible; these will be developed once necessary surveys and studies have been completed. Knowledge gaps will be addressed by recovery actions given ‘urgent’ priority included in the recovery planning approaches.

In support of the long-term goal, the following short-term recovery objectives will be addressed over the next five to ten years:

- Refine population and distribution objectives;

- Ensure the protection of critical habitat;

- Determine long-term population and habitat trends;

- Evaluate and mitigate threats to the species and its habitat;

- Determine the feasibility of relocations and captive rearing;

- Ensure efficient use of resources (human and fiscal) during recovery planning efforts; and,

- Improve awareness of the Northern Madtom and engage the public in the conservation of the species.

The overall approaches recommended to meet the recovery objectives have been organized into three categories: 1. Research and Monitoring; 2. Management and Coordination; and, 3. Stewardship, Outreach and Awareness. Each category is summarized in a table detailing specific steps with a priority ranking (urgent, necessary, beneficial), a link to the recovery objectives, the broad approach, a description of the threat addressed, and suggested outcomes or deliverables to measure progress. A more detailed narrative is included after each table when further explanation of specific approaches is required. Implementation of the following approaches will be accomplished in coordination with relevant ecosystem-based recovery teams and other relevant organizations. Within the recovery planning approaches, higher priority will be given to urgent priorities for Research and Monitoring (Table 4), as these data will be used to inform the approaches in Tables 5 and 6. Refer to Tables 7 and 9 for suggested timelines on when urgent priorities may be completed. Note that these timelines are dependent on available resources over the next five years.

| Priority | Objective addressed | Broad approach to address threats | Threats addressed | Specific steps | Outcomes or deliverables (identify measurable targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urgent | i | 1. Background surveys – extant/historical occurrences | All | Conduct targeted sampling in areas of occupied habitat as well as historically occupied habitat (e.g., Sydenham River). Use sampling techniques proven to detect Northern Madtom (e.g., night/day seining and trawling) | Will determine presence/absence, health, range, abundance, and population demographics and contribute to the identification of critical habitat. |

| Urgent | i | 2. Background surveys – new occurrences | All | Conduct targeted sampling in areas lacking Northern Madtom records but possessing potentially suitable habitat. Sampling should be done during both the day and night using sampling techniques proven to detect Northern Madtom. | May detect new occurrences of Northern Madtom. |

| Urgent | i, iii | 3. Monitoring – populations and habitat | All | Establish sampling protocol for Northern Madtom, which will be informed by the results of background surveys. Establish and implement a standardized index population and habitat monitoring program using the sampling protocol for Northern Madtom. | Will enable an assessment of changes in range, abundance, key demographic characters and changes in habitat features, extent and health. |

| Urgent | ii | 4. Research - habitat requirements (currently occupied habitat) | All | Determine the seasonal habitat needs, including home range and species movement, of all life-stages of the Northern Madtom. | Will allow for the full identification of critical habitat for Northern Madtom. Will assist with the development of a habitat model. |

| Urgent | iv | 5. Threat evaluation- exotic species | Exotic species | Investigate the impacts of Round Goby and Zebra Mussel on Northern Madtom. Studies to include impacts on Northern Madtom spawning success. | Will identify the degree to which Round Goby and Zebra Mussel may impact Northern Madtom. |

| Urgent | iv | 6. Threat evaluation – habitat loss; siltation | Physical habitat loss; siltation | Investigate the impacts of physical habitat changes on the Northern Madtom. | Will identify the degree to which the Northern Madtom is affected by physical habitat alterations (e.g., dredging, sedimentation and shoreline hardening). |

| Necessary | iv | 7. Monitoring – Zebra Mussel | Exotic species | Monitor the spread of Zebra Mussel in watersheds occupied by the Northern Madtom. | Will enable an assessment of the risk posed to Northern Madtom should Zebra Mussel spread and/or increase in number in occupied areas. |

| Necessary | v | 8. Genetic comparisons | All | Examine genetic relationships between populations as well as the amount of genetic variation within populations. Compare genetics of Canadian populations of Northern Madtom to populations in the U.S. | Will help to distinguish populations. Will contribute necessary information should population enhancement through relocations or captive rearing be required. |

| Necessary | iv | 9. Threat evaluation- contaminants | Contaminants | Investigate the impacts (lethal/sub-lethal) of pollutants in the Huron-Erie corridor, and nutrient loading in the Sydenham and Thames rivers, on Northern Madtom. | Will enable an assessment of risks and the identification of contaminants of concern for Northern Madtom. |

| Necessary | v | 10. Research – captive rearing and relocations | All | If the need for population supplementation is determined, develop relocation and captive rearing techniques and incorporate into population-specific action plans as required. Conduct population genetics research prior to captive rearing and relocation (See Approach #8). | Will help to determine the feasibility of relocations and/or captive rearing. |

1 – 2. Background surveys: The Northern Madtom is known from only five general locations in watersheds throughout its Canadian range and fewer than 100 specimens have ever been captured in Canada. If a population was actually present in the Sydenham River (this is not clear given that only one specimen was ever detected) it is believed to be extirpated as it has not been detected in the river since 1975. The Northern Madtom may be somewhat more widely distributed than currently known, as a result of its secretive behaviour, the relative lack of appropriate sampling (e.g., night seining, trawling and possibly minnow traps [Northern Madtom were caught in minnow traps by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) (2006) while monitoring a Lake Sturgeon spawning habitat rehabilitation project]) within its Canadian range, as well as possible errors in field identification (Holm and Mandrak 1998). Surveys are required in areas of current and historical occurrence to: confirm the spatial distribution of extant populations; confirm the loss of historical populations; identify potentially suitable habitat; and, to detect the presence of Round Goby and Zebra Mussel. It is recommended that the Sydenham and Thames rivers be sampled during periods of low flow (i.e., during the summer or early fall).

3. Monitoring – populations and habitat: A monitoring program is required to provide an index of abundance and trend over time data, as well as to analyze habitat use and availability and changes in these parameters over time. Sampling methods will be informed through successful protocols developed during background surveys.

10. Research – captive rearing and relocations: If the need for population supplementations is determined, source populations need to be identified. Ideally, source populations possess a high level of genetic diversity and genetic composition developed under similar historic conditions as the repatriation site. Any relocations that are considered will follow the Repatriation Approach outlined in the Essex-Erie Recovery Strategy (EERT 2008), should they be deemed necessary.

| Priority | Objective number | Broad approach | Threat addressed | Specific steps | Outcomes or deliverables (identify measurable targets) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urgent | vi | 1. Coordination with other recovery teams and relevant organizations | All | Work with relevant organizations (e.g., United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), Conservation Authorities, First Nations) and ecosystem- and single species recovery teams to share knowledge, implement recovery actions and to obtain incidental sightings. | Will combine resources, ensure information dissemination, help to prioritize most urgent actions across the species’ range and allow for a coordinated approach to recovery. |

| Urgent | vi, vii | 2. Municipal planning – involvement | Physical habitat loss | Encourage municipalities to protect habitats that are important to the Northern Madtom in their Official Plans. | Will assist with the recovery of the Northern Madtom and prevent further impairment of water quality of watersheds it inhabits. |

| Urgent | ii | 3. Habitat management | Physical habitat loss | Ensure planning and management agencies are aware of habitats that are important to Northern Madtom. | Will result in the protection of important Northern Madtom habitat from industrial and development activities (e.g., dredging, marinas). |

| Necessary | vi, vii | 4. Evaluation of watershed-scale stressors | All | In cooperation with relevant ecosystem-based recovery teams and organizations, evaluate watershed-scale stressors to populations and their habitats. | Will identify multiple stressors that may affect Northern Madtom populations. |

| beneficial | iv | 5. Exotic species management plan | Exotic species | Develop a management plan addressing potential risks and proposed actions in response to existing exotic species and to the arrival or establishment of new exotic species. | Will ensure a quick response should this threat more fully materialize. |

1. Coordination with other recovery teams and relevant organizations: Many of the threats facing the Northern Madtom are a result of habitat degradation that affects numerous aquatic species. Ecosystem-based recovery strategies, such as those for the Essex-Erie region and the Sydenham and Thames rivers, have incorporated the biological and ecological requirements of the Northern Madtom into relevant watershed-based recovery approaches as well as species specific approaches. A coordinated, cohesive approach between these teams and other relevant agencies (e.g., USGS/USFWS and First Nations) that maximizes opportunities to share resources, information and combine efficiencies is recommended.

| Priority | Objective number | Broad approach | Threat addressed | Specific steps | Outcomes or deliverables (identify measurable targets) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urgent | vi, vii | 1. Collaboration and information sharingTable notea | All | Collaborate with relevant groups, including Aboriginal groups, and recovery teams to address recovery actions of benefit to the Northern Madtom. | Will combine efficiencies in addressing common recovery actions, and ensure information is disseminated in a timely cooperative fashion. |

| urgent | vi, vii | 2. Stewardship and habitat initiativesTable notea | All | Promote stewardship among landowners abutting aquatic habitats of Northern Madtom, as well as other local residents and First Nations. | Will raise community support and awareness of recovery initiatives. Will raise profile of Northern Madtom and improve awareness of opportunities to improve water quality and species habitat. |

| urgent | iv, vi, vii | 3. Stewardship – implementation of BMPsTable notea | Physical habitat loss; Siltation; Nutrient loading; Toxic compounds |

Work with landowners and other interest groups to implement BMPs in areas where they will provide the most benefit. Encourage the completion and implementation of Environmental Farm Management Plans (EFPs) and Nutrient Management Plans (NMPs). | Will minimize threats from soil erosion, stream sedimentation, and nutrient and chemical contamination. |

| necessary | vii | 4.Communications strategy | All | Develop and implement strategy for communicating with target land users/stakeholders with respect to recovery activities as required. | Will provide a strategic basis for improving public awareness of species at risk and promote ways in which community and public involvement can be most effectively solicited for the recovery of the species. |

| necessary | vii | 5. Stewardship – financial assistance/ incentivesTable notea | Physical habitat loss; Siltation; Nutrient loading; Toxic compounds | Facilitate access to funding sources for land owner and local community groups and First Nations engaged in stewardship activities. | Will facilitate the implementation of recovery efforts, BMPs associated with water quality improvements, sediment load reduction, etc. |

| necessary | vii | 6. Awareness – addressing landowner concerns | All | Provide clear communications addressing funding opportunities and landowner concerns and responsibilities under the federal Species at Risk Act(SARA) and the provincial Endangered Species Act, 2007(ESA). | Will address landowner concerns surrounding the Northern Madtom and facilitate public interest and involvement in stewardship initiatives. |

| beneficial | iv, vii | 7. Exotic species/baitfish introductions | Exotic species | Increase public awareness of the impacts of exotic species on the natural ecosystem and encourage the use of existing exotic species reporting systems. Anglers should be discouraged from emptying the contents of their bait-buckets in waterbodies where the bait was not captured. | Will reduce the transport and release of exotics (including baitfish) and prevent their establishment in areas inhabited by the Northern Madtom that do not already have exotic species. |

2. Stewardship and habitat initiatives:Basin-wide efforts are required to improve habitat quality at locations currently and historically occupied by Northern Madtom. This represents an important opportunity to engage land owners, local communities, Aboriginal groups and stewardship councils on the issues of Northern Madtom recovery, ecosystem and environmental health, clean water protection, nutrient management, BMPs, stewardship projects and associated financial incentive programs. Towards this end, the recovery team will work closely with relevant organizations as well as the three ecosystem-based recovery teams, all of which have established on-going stewardship programs that will benefit the species.

3. Stewardship – implementation of BMPs:Implementation will be informed through proposed research on evaluating threat factors for the Northern Madtom. The implementation of BMPs will be largely facilitated through established stewardship programs. Additional stewardship programs will be directed as necessary to areas outside the boundaries of ecosystem-based programs. To be effective, BMPs should be targeted to address the primary threats affecting critical habitat. BMPs implemented will include those relating to: the establishment of riparian zones; soil conservation; herd management; septic improvements to prevent nutrient run-off; nutrient and manure management; and, tile drainage. Establishing riparian zones reduces nutrient (nitrogen and phosphorous) and sediment inputs to receiving waters and overland run-off. Restriction of livestock from watercourses leads to reductions in erosion and sediment and nutrient loadings. Nutrient and manure management will reduce nitrogen and phosphorous inputs into adjacent waterbodies, thereby improving water quality. Low-till practices can reduce soil erosion and improve soil structure while reducing the sediment loads of adjacent watercourses. Environmental Farm Plans prioritize BMP implementation at the level of individual farms and are often a pre-requisite for funding programs.

The overall success of implementing the recommended recovery approaches will be evaluated primarily through routine population (distribution and abundance) and habitat (quality and quantity) surveys and monitoring. During the next five years, the recovery team will focus on completing recovery actions identified as “urgent” for the Northern Madtom. The recovery strategy will be reported on in five years to evaluate the progress made toward short-term and long-term targets, and the current goals and objectives will be reviewed within an adaptive management planning framework with input from ecosystem recovery teams. Performance measures to evaluate the recovery process in meeting recovery objectives over the next five years are outlined in Table 7.

| Recovery objective | Performance measures |

|---|---|

| 1. Refine population and distribution objectives. | Completion of background surveys required to fully describe all extant populations by 2014. |

| 2. Ensure the protection of critical habitat. | Completion of activities outlined in the Schedule of Studies for the complete determination of critical habitat within the proposed timelines. |

| 3. Determine long-term population and habitat trends. | Population and habitat monitoring program established by 2013 (within regions currently identified as critical habitat). |

| 4. Evaluate and mitigate threats to the species and its habitat. | Report results of research on the impacts/effects of competition by the Round Goby by 2014. Report results of additional research that assists with the evaluation of impacts/effects of threats to the Northern Madtom by 2016. Quantification of BMPs (e.g., number of NMPs or EFPs established) implemented to address threats by 2013. |

| 5. Examine the feasibility of relocations and captive rearing. | Report on the feasibility (and need) for relocations and captive rearing of the Northern Madtom. |

| 6. Ensure efficient use of resources (human and fiscal) during recovery planning efforts. | Collaboration with all ecosystem recovery teams and other stakeholders. |

| 7. Improve awareness of the Northern Madtom and engage the public in the conservation of the species. | Document any changes in public perceptions and support for identified recovery actions through guidance identified in the communications strategy (by 2014). |

The identification of critical habitat for Threatened and Endangered species (on Schedule 1) is a requirement of the SARA. Once identified, SARA includes provisions to prevent the destruction of critical habitat. Critical habitat is defined under section 2(1) of SARA as:

SARA defines habitat for aquatic species at risk as:

For the Northern Madtom, critical habitat has been identified to the extent possible, using the best information currently available. The critical habitat identified in this recovery strategy describes the geospatial areas that contain the habitat necessary for the survival or recovery of the species. The current areas identified may be insufficient to achieve the population and distribution objectives for the species. As such, a schedule of studies has been included to further refine the description of critical habitat (in terms of its biophysical functions/features/attributes as well as its spatial extent) to support its protection.

Using the best available information, critical habitat has been identified using a ‘bounding box’ approach for populations in the Detroit River and the lower Thames River where the Northern Madtom presently occurs; additional areas of potential critical habitat within Lake St. Clair will be considered in collaboration with Walpole Island First Nation.

This approach requires the use of essential functions, features and attributes for each life-stage of the Northern Madtom to identify patches of critical habitat within the ‘bounding box’ which is defined by occupancy data for the species. Life stage habitat information was summarized in chart form using available data and studies referred to in Section 1.4.1 (Habitat and biological needs). The bounding box approach was the most appropriate, given the limited information available for the species and the lack of detailed habitat mapping for these areas. Where habitat information was available (e.g., Aquatic Landscape Inventory System (ALIS)), it was used to identify critical habitat. Specific methods and data used (such as the use of ALIS) are summarized below.

Thames River: Recent sampling datasets used in the identification of critical habitat for the Northern Madtom for the Thames River are summarized in Table 3; although the species was not detected during targeted sampling by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) in 2008, the species was captured incidentally during surveys conducted from 2003-2008. The most recent records for Northern Madtom in the Thames River resulted from sampling conducted by two graduate students studying the Eastern Sand Darter (See Table 3).

Within the Thames River, critical habitat was informed through the use of an ecological classification system (i.e., ALIS). The ALIS classification was developed by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) to define stream segments based on a number of unique characteristics found only within those valley segments. Each valley segment is defined by a collection of landscape variables that are believed to have a controlling effect on the biotic and physical processes within the catchment.

Therefore, if a population has been found in one part of the ecological classification, there is no reason to believe that it would not be found in other spatially contiguous areas of the same valley segment. Critical habitat for the Northern Madtom within the Thames River was therefore identified as the reach of river that includes all contiguous ALIS segments from the uppermost stream segment with the species present to the lowermost stream segment with the species present.

Detroit River : Recent sampling datasets (2003-2009) used in the identification of critical habitat for the Northern Madtom for the Detroit River are summarized in Table 3. To define the ‘bounding box’ for occupied locations at Peche Island and Fighting Island, a ‘population range envelope’ was used. The population range envelope is a projected rectangle around the occurrence points based on the minimum and maximum latitude and longitude values. In order to account for normal movements within a home range, the envelope was buffered by a distance of approximately 51.55 m. This buffer was determined using the radius of the home range of the Northern Madtom, which was calculated using a body size – waterbody size dependent method (Woolnough et al. 2009).