Recovery Strategy for the Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) in Canada - 2016

- Part 1 - Federal Addition to the Recovery Strategy for the Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) in Ontario, prepared by Environment Canada.

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Additions and modifications to the adopted document

- 1. Species Status Information

- 2. Recovery Feasibility

- 3. Population and Distribution Objectives

- 4. Broad Strategies and General Approaches to Meet Objectives

- 5. Critical Habitat

- 6. Measuring Progress

- 7. Statement on Action Plans

- 8. Effects on the Environment and Other Species

- References

- Appendix A: Subnational Conservation Ranks of Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) in Canada and the United States

- Part 2 - Recovery Strategy for the Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) in Ontario, prepared by Jefferson Salamander Recovery Team for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources.

- Part 3 - Jefferson Salamander: Ontario Government Response Statement, prepared by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources.

Environment Canada. 2016. Recovery Strategy for the Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) in Canada. Species at Risk Act (SARA) Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. 26 pp. + Annexes.

For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry.

Cover illustration: ©Jennifer McCarter, The Nature Conservancy of Canada

Également disponible en français sous le titre

« Programme de rétablissement de la salamandre de Jefferson (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) au Canada - 2016 »

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996), the federal, provincial, and territorial governments agreed to work together on legislation, programs, and policies to protect wildlife species at risk throughout Canada.

In the spirit of cooperation of the Accord, the Government of Ontario has given permission to the Government of Canada to adopt the Recovery Strategy for the Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) in Ontario (Part 2) under Section 44 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA).Environment Canada has included an addition (Part 1) which completes the SARA requirements for this recovery strategy.

Environment Canada is adopting the provincial recovery strategy with the exception of section 2, Recovery. In place of section 2, Environment Canada is establishing a population and distribution objective and performance indicators, is adopting the government-led and government-supported actions of the Jefferson Salamander Ontario Government Response StatementFootnote1.1 (Part 3) as the population and distribution objective and the broad strategies and general approaches to meet the population and distribution objective; and is adopting the habitat regulated under Ontario's Endangered Species Act, 2007 as critical habitat for the Jefferson Salamander.

The federal recovery strategy for the Jefferson Salamander in Canada consists of three parts:

Part 1 – Federal Addition to the Recovery Strategy for the Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) in Ontario, prepared by Environment Canada.

Part 2 - Recovery Strategy for the Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) in Ontario, prepared by Jefferson Salamander Recovery Team for the Ontario Ministry of Natural ResourcesFootnote2.

Part 3 – Jefferson Salamander: Ontario Government Response Statement, prepared by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources.

The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996) agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species and are required to report on progress five years after the publication of the final document on the SAR Public Registry.

The Minister of the Environment is the competent minister for the recovery of the Jefferson Salamander and has prepared the federal component of this recovery strategy (Part 1), as per section 37 of SARA. SARA section 44 allows the Minister to adopt all or part of an existing plan for the species if it meets the requirements under SARA for content (sub-sections 41(1) or (2)). The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (now the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry) led the development of the attached recovery strategy for the Jefferson Salamander (Part 2) in cooperation with Environment Canada.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy and will not be achieved by Environment Canada, or any other jurisdiction alone. All Canadians are invited to join in supporting and implementing this strategy for the benefit of the Jefferson Salamander and Canadian society as a whole.

This recovery strategy will be followed by one or more action plans that will provide information on recovery measures to be taken by Environment Canada and other jurisdictions and/or organizations involved in the conservation of the species. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities, and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

The recovery strategy sets the strategic direction to arrest or reverse the decline of the species, including identification of critical habitat to the extent possible. It provides all Canadians with information to help take action on species conservation. When the recovery strategy identifies critical habitat, there may be future regulatory implications, depending on where the critical habitat is identified. SARA requires that critical habitat identified within federal protected areas be described in the Canada Gazette, after which prohibitions against its destruction will apply. For critical habitat located on federal lands outside of federal protected areas, the Minister of the Environment must either make a statement on existing legal protection or make an order so that the prohibition against destruction of critical habitat applies. For critical habitat located on non-federal lands, if the Minister of the Environment forms the opinion that any portion of critical habitat is not protected by provisions in or measures under SARA or other Acts of Parliament, and not effectively protected by the laws of the province or territory, SARA requires that the Minister recommend that the Governor in Council make an order to extend the prohibition against destruction of critical habitat to that portion. The discretion to protect critical habitat on non-federal lands that is not otherwise protected rests with the Governor in Council.

The federal addition was prepared by Jennie Pearce (Pearce & Associates Ecological Research). Additional preparation and review of the document was completed by Rachel deCatanzaro, Angela McConnell, and Allison Foran (Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario). This federal addition benefited from input, review, and suggestions from the following individuals and organizations: Krista Holmes, Madeline Austen, Lesley Dunn, and Elizabeth Rezek (Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario); Paul Johanson (Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service – National Capital Region) and Joe Crowley and Jay Fitzsimmons (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry). Information contributed by Talena Kraus (Artemis Eco-works), Kari Van Allen and Angela Darwin (Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario) and Barbara Slezak (formerly Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service-Ontario) is also gratefully acknowledged.

Acknowledgment and thanks is given to all other parties that provided advice and input used to help inform the development of this recovery strategy including various Aboriginal organizations and individuals, individual citizens, and stakeholders who provided input and/or participated in consultation meetings.

The following sections have been included to address specific requirements of the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA) that are not addressed in the Province of Ontario's Recovery Strategy for the Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) in Ontario (Part 2) and to provide updated or additional information.

Under SARA, there are specific requirements and processes set out regarding the protection of critical habitat. Therefore, statements in the provincial recovery strategy referring to protection of the species' habitat may not directly correspond to federal requirements, and are not being adopted by Environment Canada as part of the federal recovery strategy. Whether particular measures or actions will result in protection of critical habitat under SARA will be assessed following publication of the final federal recovery strategy.

The Jefferson Salamander is listed as EndangeredFootnote3 under the Ontario Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). and is currently listed as ThreatenedFootnote4 on Schedule 1 of the federal SARA.

Globally, the Jefferson Salamanderis ranked Apparently SecureFootnote5(G4) (NatureServe 2012a). At the national scale, it is ranked as ImperiledFootnote6 N2) in Canada and Apparently Secure (N4) in the United States. At the sub-national level, it is ranked as Imperiled (S2) in Ontario, and Imperiled to Apparently Secure across its range in the United States (Appendix A).

In Canada, the species only occurs in Ontario. The Ontario population of the Jefferson Salamander occurs at the northern limit of the species' range in North America. As of October 2008, there were an estimated 328 known breeding ponds representing approximately 27 geographically discrete populations within the province. The Canadian population of the Jefferson Salamander probably constitutes between one and three percent of the species' global distribution (Jefferson Salamander Recovery Team 2010). The area of occupancyFootnote7 of the Jefferson Salamander in Canada has been estimated to be around 196 km2 (COSEWIC 2010).

Based on the following four criteria outlined in the draft SARA Policies (Government of Canada 2009), there are unknowns regarding the feasibility of recovery of the Jefferson Salamander. In keeping with the precautionary principle, a full recovery strategy has been prepared as would be done when recovery is determined to be feasible

Individuals of the wildlife species that are capable of reproduction are available now or in the foreseeable future to sustain the population or improve its abundance.

Yes. As of October 2008, Jefferson Salamanders had been confirmed breeding (in at least one year since 1998) at approximately 328 breeding ponds in Ontario, representing approximately 27 geographically discrete populations (Jefferson Salamander Recovery Team 2010). The total number of Jefferson Salamanders in Ontario is unknown, but COSEWIC (2010) estimated that there may be fewer than 2,500 adults.

Sufficient suitable habitat is available to support the species or could be made available through habitat management or restoration.

Unknown. Within the species' current range, suitable habitat exists, but is highly fragmented and nearby development activities may be causing habitat degradation. The availability of suitable habitat (both terrestrial and breeding ponds) is recognized as a major limiting factor for the species (COSEWIC 2010; Jefferson Salamander Recovery Team 2010). Although little information on population trends is available, annual observations for several extant populations have documented a severe decline in the number of egg masses observed, possibly due to habitat degradation at these extant populations.

The primary threats to the species or its habitat (including threats outside Canada) can be avoided or mitigated.

Unknown. Activities associated with urbanization, aggregate extraction and other resource developments pose the most significant threat to the Jefferson Salamander. These activities can result in the direct loss, degradation or fragmentation of habitat (e.g., through loss of natural cover), as well as indirect degradation or loss of breeding habitat through alterations to the hydrologic regime (water table, groundwater and surface water flows, wetland hydroperiod, etc.). In addition, roads may threaten Jefferson Salamanders as some roads present a barrier to dispersal and may result in mortality of individuals from vehicles. The effects of these threats may be cumulative. Threats to each extant population have not been quantified or monitored, and the effectiveness of mitigation efforts is currently unknown (Jefferson Salamander Recovery Team 2010). While it may not be possible to reverse some of the effects of existing or past developments, it is expected that with further investigation into both direct and indirect threats to Jefferson Salamander habitat posed by development (including an examination of cause-effect relationships) and the relative severity of threats to populations, threats from development activities and roads can be reduced to some degree through land management and stewardship actions.

Recovery techniques exist to achieve the population and distribution objectives or can be expected to be developed within a reasonable timeframe.

Yes. The population and distribution objective consists of maintaining or increasing the species' area of occupancy within its existing Ontario range. Research is required to investigate the relative severity of direct and indirect threats to individual populations of Jefferson Salamander (Jefferson Salamander Recovery Team 2010) and identify actions to recover populations. While there may be challenges associated with their implementation, land management and stewardship techniques to achieve recovery of the species – such as land use planning, wetland creation/ restoration, and techniques to mitigate road mortality – do exist.

The provincial Recovery Strategy for the Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) in Ontario contains the following recovery goal:

- The recovery goal is to ensure that existing threats to populations and habitat of the Jefferson Salamander are sufficiently removed to allow for the long-term persistence and expansion of the species within its existing Canadian range.

The Government Response Statement for the Government of Ontario lists the following goal for the recovery of the Jefferson Salamander in Ontario:

- The government's goal for the recovery of the Jefferson Salamander is to ensure that threats to populations and habitat are addressed, in order to allow for the long-term persistence and expansion of the species within its existing Ontario range.

Environment Canada supports the provincial recovery goal to allow for the long-term persistence and expansion of the Jefferson Salamander in Ontario. To meet the requirements and processes set out in SARA, Environment Canada has refined this recovery goal into a population and distribution objective for the species. The population and distribution objective established by Environment Canada for the Jefferson Salamander is to:

Maintain, and to the extent that it is biologically and technically feasible, increase the species' area of occupancy within its existing Ontario range.

Estimates of population size for the Jefferson Salamander are difficult to obtain because of the presence of unisexual salamandersFootnote8 which are morphologically similar to the Jefferson Salamander, and comprise approximately 90% of local populations (Bogart 2003; Bogart and Klemens 1997, 2008; Bi and Bogart 2010). Adults are also difficult to observe or capture except at breeding ponds, where they may be present for only a few days. Furthermore, breeding may not occur at a pond every year (Weller 1980). For these reasons, the population and distribution objective is based on area of occupancy rather than on population abundance. Population abundance, though difficult to measure, will also likely increase along with increases to the area of occupancy.

In order to achieve the population and distribution objective, addressing threats to the Jefferson Salamander and its habitat will be important. Suitable habitat for the Jefferson Salamander is limited in Ontario, severely fragmented and occurs within an urban and rural landscape with increasing development pressures, ongoing aggregate extraction activities and/or other development activities. These development activities can directly or indirectly lead to habitat loss or degradation (i.e. through pollution, changes in the water regime, etc.). Many historical breeding sites may no longer support Jefferson Salamanders, and the number of Jefferson Salamanders in extant populations may be declining (COSEWIC 2010). Jefferson Salamanders appear to have strong site and pond fidelity, and are long-lived (up to 30 years) (Weller 1980; Thompson et al. 1980; Jefferson Salamander Recovery Team 2010). Provided other threats to Jefferson Salamander individuals (e.g., road mortality, unauthorized collection) are managed and mitigated, viable populations would be expected to persist over long time frames where sufficient suitable habitat exists, and expansion of populations may be encouraged through maintaining currently unoccupied adjacent suitable habitat.

The government-led and government-supported actions table from the Jefferson Salamander Ontario Government Response Statement (Part 3) are adopted as the broad strategies and general approaches to meet the population and distribution objective. Environment Canada is not adopting the approaches identified in section 2 of the Recovery Strategy for the Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) in Ontario (Part 2).

Section 41(1)(c) of SARA requires that recovery strategies include an identification of the species' critical habitat, to the extent possible, as well as examples of activities that are likely to result in its destruction. Under SARA, critical habitat is "the habitat that is necessary for the survival or recovery of a listed wildlife species and that is identified as the species' critical habitat in the recovery strategy or in an action plan for the species".

Identification of critical habitat is not a component of the provincial recovery strategy under the Province of Ontario's ESA. However, following the completion of the provincial recovery strategy for the Jefferson Salamander, a provincial habitat regulation was developed and came into force February 18, 2010. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protectedFootnote9 as the habitat of this species by the Province of Ontario. The habitat regulation identifies the geographic area within which the habitat for the species is prescribed and the regulation may apply and explains how the boundaries of regulated habitat are determined (based on biophysical and other attributes). The regulation is dynamic and automatically in effect whenever the description(s) of the regulation are met within a specified geographic area.

Environment Canada adopts the description of the Jefferson Salamander habitat under section 28 of Ontario Regulation 242/08Footnote10 made under the provincial ESA as the critical habitat in this federal recovery strategy. The area defined under Ontario's habitat regulation contains the biophysical attributes required by the Jefferson Salamander to carry out its life processes. To meet specific requirements of SARA, the biophysical attributes of critical habitat are provided below.

The areas prescribed under Ontario Regulation 242/08 – Jefferson Salamander habitat are described as follows:

- 28. For the purpose of clause (a) of the definition of "habitat" in subsection 2 (1) of the Act, the following areas are prescribed as the habitat of the Jefferson Salamander:

- 1. In the City of Hamilton, the counties of Brant, Dufferin, Elgin, Grey, Haldimand, Norfolk and Wellington and the regional municipalities of Halton, Niagara, Peel, Waterloo and York,

- i. a wetland, pond or vernal or other temporary pool that is being used by a Jefferson Salamander or Jefferson dominated polyploidFootnote11 or was used by a Jefferson Salamander or Jefferson dominated polyploid at any time during the previous five years,

- ii. an area that is within 300 metres of a wetland, pond or vernal or other temporary pool described in subparagraph i and that provides suitable foraging, dispersal, migration or hibernation conditions for Jefferson Salamanders or Jefferson dominated polyploids,

- iii. a wetland, pond or vernal or other temporary pool that,

- A. would provide suitable breeding conditions for Jefferson Salamanders or Jefferson dominated polyploids.

- B. is within one kilometre of an area described in subparagraph i, and

- C. is connected to the area described in subparagraph i by an area described in subparagraph iv, and

- iv. an area that provides suitable conditions for Jefferson Salamanders or Jefferson dominated polyploids to disperse and is within one kilometre of an area described in subparagraph i. O. Reg. 436/09, s. 1.

- 1. In the City of Hamilton, the counties of Brant, Dufferin, Elgin, Grey, Haldimand, Norfolk and Wellington and the regional municipalities of Halton, Niagara, Peel, Waterloo and York,

The habitat for the Jefferson Salamander is protected under the ESA until it has been demonstrated that Jefferson Salamander and jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids have been absent for a period of at least five years. Terrestrial habitat includes all of the areas and features described above that extend radially 300 m from the edge of the breeding pond. The 300 m distance is based on data from telemetry studies (OMNR 2008 unpublished data) as the habitat area required to support 95% of the adult population for each breeding location. The 1 km distance used to identify dispersal corridors is based on the maximum migratory distance of adults from the breeding pond into surrounding habitat (Faccio 2003; Semlitsch 1998; OMNR 2008 unpublished data).

While jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids will not be protected under the ESA or SARA, they are included in the regulation as surrogates for pure Jefferson Salamanders. The presence of jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids indicates that a pure breeding Jefferson Salamander is present to act as a sperm donor (Bogart and Klemens 1997, 2008). Furthermore, jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids use the same habitats as pure Jefferson Salamanders and, therefore, a jeffersonianum-dominated polyploid associated with a specific habitat (e.g., breeding pond) provides a good indication that pure Jefferson Salamanders (which are very rare and difficult to find) also use that habitat.

The biophysical attributes of critical habitat include the characteristics described below.

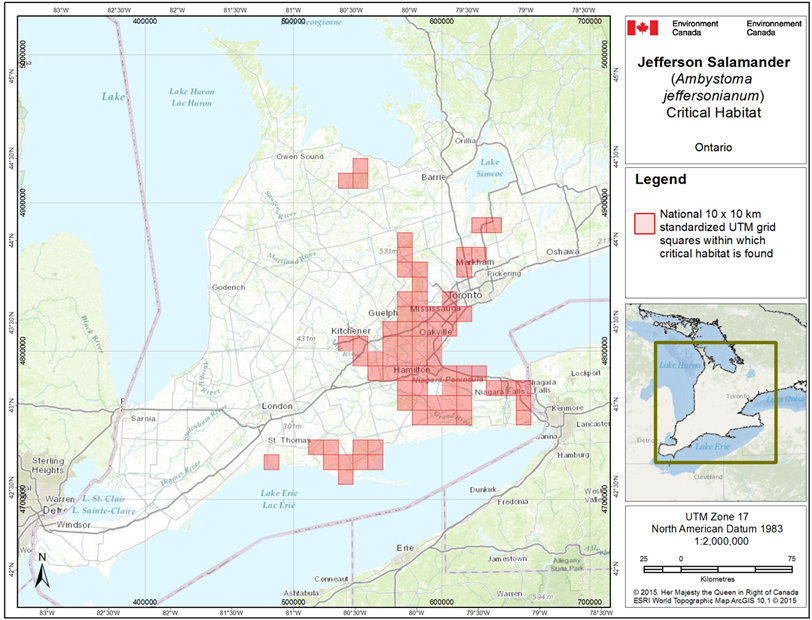

Through this recovery strategy, the areas prescribed as habitat for the Jefferson Salamander under section 28 of Ontario Regulation 242/08 become critical habitat identified under SARA. Since the regulation is dynamic and automatically in effect whenever the conditions described in the regulation are met, if any new locations of the Jefferson Salamander (or Ambystoma jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids) are confirmed within the geographic areas listed under subsection (1) of the regulation (see Figure 1), the habitat regulation under the ESA applies. Should new occurrences of Jefferson Salamander be identified that meet the criteria above, the additional crtical habitat will be identified in an updated recovery strategy or a subsequent action plan.

Because several or many breeding ponds within an area may support a discrete population, critical habitat for the Jefferson Salamander is made up of core areas and dispersal corridors. Critical habitat core areas are comprised of the breeding ponds (i.e., the areas described in 28(1)(i) and 28(1)(iii) of the Ontario Regulation 242/08), as well as the areas within 300 m of occupied breeding ponds that provide suitable conditions for foraging, dispersal, migration or hibernation (i.e., the areas described in 28(1)(ii) of the Ontario Regulation 242/08). Critical habitat dispersal corridors consist of the habitats that connect core areas and provide suitable conditions for dispersal (i.e., the areas described in 28(1)(iv) of the Ontario Regulation 242/08).

At this time, breeding ponds that provide the basis for delineating critical habitat are represented using available wetland habitat mapping. Where breeding ponds that support Jefferson Salamander are not known (or not available in existing wetland habitat mapping), a generalized area (represented by a radial distance around an observation record (300 m, and 1 km where appropriate; see habitat regulation)) is used to represent the habitat and direct recovery and protection activities until information allowing identification of more detailed critical habitat boundaries is obtained. Because small, temporal or ephemeral features are not well captured through existing land classification mapping, especially where field verification has not taken place, precaution should be taken when biophysical attributes of suitable habitat are represented by available thematic data.

Application of the critical habitat criteria above to the best available dataFootnote13, identifies critical habitat of Jefferson Salamander (or jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids) in Canada. The total area within which critical habitat for Jefferson Salamander is found is 56,540 haFootnote14 (Figure 2; see also Table 1). The critical habitat identified is considered a partial identification of critical habitat, and is insufficient to meet the population and distribution objective for the Jefferson Salamander. Additional surveys are required to confirm habitat occupancy at locations where Jefferson Salamader records are older than thirty years or are spatially imprecise. A schedule of studies has been developed to provide the information necessary to complete the identification of critical habitat (see section 5.2).

Human-created features (e.g., old farm ponds and dug ponds) are included in the identification of critical habitat unless there is evidence that Jefferson Salamander or jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids have been absent for a period of at least five years. Newly created artificial habitat (i.e., created breeding ponds) will not be included in the identification of critical habitat until there is evidence of use. In addition, the following features are not considered suitable (do not meet the biophysical attributes described above) and are not part of critical habitat: existing houses, buildings, structures, quarries, and other pre-existing industrial land uses; major roads; and open areas which do not directly separate breeding ponds from forested areas.

Critical habitat for the Jefferson Salamander is presented using 10 x 10 km UTM grid squares. The UTM grid squares presented in Figure 2 are part of a standardized grid system that indicates the general geographic areas containing critical habitat, which can be used for land use planning and/or environmental assessment purposes, and is a scale appropriate to reduce risks to the Jefferson Salamander and its habitat (e.g., to human disturbance). The areas of critical habitat within each grid square occur where the description of critical habitat is met. More detailed information on the regulated habitat may be requested on a need-to-know-basis from the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. More detailed information on critical habitat to support protection of the species and its habitat may be requested on a need-to-know basis by contacting Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service at ec.planificationduretablissement-recoveryplanning.ec@canada.ca.

Long description for Figure 1

Long description for Figure 2

| 10 x 10 km Standardized UTM Grid Square IDNoteaof Table 1 | UTM Grid Square CoordinatesNotebof Table 1a Easting |

UTM Grid Square CoordinatesNotebof Table 1b Northing |

Land TenureNotecof Table 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17TMH82 | 480000 | 4720000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH13 | 510000 | 4730000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH22 | 520000 | 4720000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH23 | 520000 | 4730000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH31 | 530000 | 4710000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH32 | 530000 | 4720000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH42 | 540000 | 4720000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH43 | 540000 | 4730000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH49 | 540000 | 4790000 | Other Federal Land and Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH52 | 550000 | 4720000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH53 | 550000 | 4730000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH58 | 550000 | 4780000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH59 | 550000 | 4790000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH68 | 560000 | 4780000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH69 | 560000 | 4790000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH76 | 570000 | 4760000 | Other Federal Land and Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH77 | 570000 | 4770000 | Other Federal Land and Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH78 | 570000 | 4780000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH79 | 570000 | 4790000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH85 | 580000 | 4750000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH86 | 580000 | 4760000 | Other Federal Land and Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH87 | 580000 | 4770000 | Other Federal Land and Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH88 | 580000 | 4780000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH89 | 580000 | 4790000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH95 | 590000 | 4750000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH96 | 590000 | 4760000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH98 | 590000 | 4780000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNH99 | 590000 | 4790000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ30 | 530000 | 4800000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ40 | 540000 | 4800000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ60 | 560000 | 4800000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ61 | 560000 | 4810000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ70 | 570000 | 4800000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ71 | 570000 | 4810000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ72 | 570000 | 4820000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ73 | 570000 | 4830000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ75 | 570000 | 4850000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ76 | 570000 | 4860000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ77 | 570000 | 4870000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ80 | 580000 | 4800000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ81 | 580000 | 4810000 | Other Federal Land and Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ82 | 580000 | 4820000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ83 | 580000 | 4830000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ84 | 580000 | 4840000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ85 | 580000 | 4850000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ90 | 590000 | 4800000 | Other Federal Land and Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ91 | 590000 | 4810000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNJ92 | 590000 | 4820000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNK31 | 530000 | 4910000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNK41 | 540000 | 4910000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TNK42 | 540000 | 4920000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPH05 | 600000 | 4750000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPH06 | 600000 | 4760000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPH07 | 600000 | 4770000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPH08 | 600000 | 4780000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPH15 | 610000 | 4750000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPH16 | 610000 | 4760000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPH17 | 610000 | 4770000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPH18 | 610000 | 4780000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPH28 | 620000 | 4780000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPH37 | 630000 | 4770000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPH55 | 650000 | 4750000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPH56 | 650000 | 4760000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPH57 | 650000 | 4770000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPJ01 | 600000 | 4810000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPJ02 | 600000 | 4820000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPJ03 | 600000 | 4830000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPJ12 | 610000 | 4820000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPJ15 | 610000 | 4850000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPJ16 | 610000 | 4860000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPJ26 | 620000 | 4860000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPJ28 | 620000 | 4880000 | Non-federal Land |

| 17TPJ38 | 630000 | 4880000 | Non-federal Land |

Long description for Table 1 - Part 1

| Description of Activity | Rationale | Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| Confirm habitat occupancy in locations where Jefferson Salamander records are older than thirty years, spatially imprecise, or cannot be associated to specific locations. | This activity is needed to complete critical habitat identification. | 2016 - 2026 |

Understanding what constitutes destruction of critical habitat is necessary for the protection and management of critical habitat. Destruction is determined on a case by case basis. Destruction would result if part of the critical habitat was degraded, either permanently or temporarily, such that it would not serve its function when needed by the species. Destruction may result from a single activity or multiple activities at one point in time or from the cumulative effects of one or more activities over time (Government of Canada 2009).

Destruction of critical habitat for the Jefferson Salamander can occur at a variety of scales and in both aquatic and terrestrial habitats. It may occur from an activity taking place either within or outside of the critical habitat boundary and it may occur in any season of the year. Within the critical habitat boundary, activities may affect core habitat areas which include breeding ponds and the areas within 300 m of occupied breeding ponds that provide suitable conditions for foraging, dispersal, migration or hibernation (i.e., the areas described in 28 (1) (i-iii) of the Ontario Regulation 242/08). Activities may also affect dispersal corridors that connect core areas (i.e., the areas described in 28 (1) (iv) of the Ontario Regulation 242/08). Within dispersal corridors it is most important to maintain habitat permeability (movement through connective habitat to access adjacent core areas) and, as a result, certain activities that are likely to cause destruction in core areas may not cause destruction in corridors so long as sufficient habitat permeability is maintained. Activities taking place outside of the critical habitat boundary are also less likely to cause destruction of critical habitat than those taking place within the critical habitat boundary.

Activities described in Table 3 are examples of those likely to cause destruction of critical habitat for the species; however, destructive activities are not necessarily limited to those listed.

| Description of Activity | Description of Effect in Relation to Function Loss | Where activity may cause destruction of critical habitat - Within critical habitat boundary - Core |

Where activity may cause destruction of critical habitat - Within critical habitat boundary - Dispersal corridor |

Where activity may cause destruction of critical habitat - Outside critical habitat boundary |

Details of effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development activities (e.g., tree harvesting, site clearing and grading, stormwater management, surface paving, etc.) or other activities that alter site cover and/or hydrology | Tree harvesting, site clearing (e.g., for urban development, aggregate extraction, or resource development) and other activities that result in the net removal, disturbance or destruction of cover objects (e.g., rocks, logs or debris) may result in the direct loss of suitable terrestrial microhabitat characteristics which the species relies on for foraging, for maintaining hydration, for protective cover, and for overwintering. Site clearing and grading may alter the topography and the hydrology (drainage patterns, water table, groundwater flow) of the site. Stormwater management and increases in impervious surfaces may also alter site hydrology. These hydrologic changes may destroy or degrade breeding and/or foraging habitat by modifying or disrupting water flow, water balance, wetland hydroperiodsFootnote1, wetland function or soil moisture. Large-scale developments (e.g., urbanization), may remove canopy, alter watercourses for snowmelt and runoff, and/or draw down the water table and therefore may result in the reduction of vernal pond "envelopes" and buffer zones or premature drying of ponds, and thereby destroy, damage or fragment habitat. |

X | X | X | Activities within critical habitat core areas that alter cover or the hydrologic regime are highly likely to result in direct destruction at any time of the year because they would degrade habitat required by all life stages for survival. If grading or other activities that alter water flows occur outside of critical habitat or in corridors, it could result in the indirect destruction of critical habitat by altering water regimes within critical habitat thereby reducing or eliminating breeding habitat. Large-scale developments within or adjacent to critical habitat may cause destruction of critical habitat at any time of year. If it occurs within critical habitat core areas, it is highly likely to cause destruction; if it occurs in corridors or adjacent to critical habitat, effects would most likely be cumulative and whether or not they result in destruction would likely depend on the extent and location of the development. |

| Erecting barriers (e.g. silt fences or drainage ditches) | Temporary and permanent structures including silt fences erected during construction, or drainage ditches, create physical barriers within the habitat that may hinder or prevent migration of salamanders, thereby preventing them from accessing habitats required to carry out life processes (e.g., breeding, foraging, overwintering) or to migrate among sites. | X | X | - | This activity must occur within the bounds of critical habitat to cause its destruction, and the likelihood of it causing destruction would depend in large part on the configuration of the barrier and the time of year that it is in place. If this activity occurs within critical habitat core areas, it could cause destruction if it prevents access to areas required by the Jefferson Salamander at one or more life stages. If this activity were to occur in early spring (typically late March to early April) it could prevent or impair breeding, or prevent or impair adults from returning to foraging habitat. If this activity were to occur in late summer/early fall (typically mid-July to mid-September), this activity could prevent or impede dispersal by juveniles from breeding habitat to foraging and overwintering habitat. If this activity occurs within critical habitat corridors, it may cause destruction if it eliminates the function of the corridor. |

| Building or upgrading roads | If it occurs within critical habitat, this activity could result in the loss or degradation of suitable habitat for all life stages through removal of vegetative cover and conversion to impermeable surfaces (see above). The construction or upgrading of roads can also lead to fragmentation of critical habitat by forming physical barriers that impede dispersal (e.g., steep roadside slopes, large roads with concrete lane dividers), thereby preventing Jefferson Salamander from accessing habitats required to carry out life processes or to migrate among sites, and by increasing mortality (e.g., greater risk of desiccation, vehicle collision and predation). In addition, if this activity occurs within or near critical habitat, chemicals and pollutants from roads (e.g., salt, metals, products of combustion) can enter breeding ponds, degrade habitat and cause toxic effects. |

X | X | X | The effects of this activity can be both direct (e.g., loss of cover, creation of a barrier that fragments habitat) and indirect or cumulative (e.g., pollution). If the effects of the activity are permanent (e.g., paving natural habitat), the activity is likely to cause destruction of habitat if undertaken at any time of the year. However, if activities do not have lasting effects (e.g., upgrading of a road that does not result in further reducing habitat permeability or increasing pollution), it may only cause destruction if conducted when the species is undertaking terrestrial movements (typically late March to early April; and mid-July to mid-September). This activity is highly likely to cause destruction if it occurs within critical habitat core areas, because it would reduce access to areas required by the Jefferson Salamander at one or more life stages. If this activity occurs within critical habitat corridors, it is also highly likely to cause destruction by eliminating the function of the corridor. If this activity occurs outside of critical habitat, it may result in the indirect destruction of critical habitat through the introduction of chemical pollution (e.g., salt) into wetlands within critical habitat. |

| Operation of heavy equipment (e.g., forestry equipment) or heavy use by ATVs | The operation of heavy equipment and heavy use of ATVs (e.g., repeated travel along a path) to the extent that the activity results in the loss of vegetation or microhabitat features, alteration of vernal pool hydrology, or filling, sedimentation or pollution of vernal pools, could destroy, damage or isolate/fragment breeding or terrestrial habitat. | X | - | - | If this activity occurs within critical habitat core areas at any time of the year, with the exception of winter months when the ground is snow covered and frozen, it is highly likely to have direct effects on critical habitat. |

| Addition of carnivorous fish to breeding ponds | Addition of carnivorous fish to ponds would destroy breeding habitat because fish prey upon all life stages of salamanders and would therefore reduce the survival and reproductive success of Jefferson Salamander individuals. | X | - | - | If this activity occurs within critical habitat core areas, at any time of the year, it is highly likely to result in its destruction because it would directly eliminate breeding habitat. |

Long description for Table 2 - Part 1

The performance indicator presented below provides a way to define and measure progress toward achieving the population and distribution objective. Every five years, success of recovery strategy implementation will be measured against the following performance indicator:

- The area of occupancy of the Jefferson Salamander in Ontario has been maintained or increased.

One or more action plans will be completed and posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry for the Jefferson Salamander by December 2022.

A strategic environmental assessment (SEA) is conducted on all SARA recovery planning documents, in accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals. The purpose of a SEA is to incorporate environmental considerations into the development of public policies, plans, and program proposals to support environmentally sound decision-making and to evaluate whether the outcomes of a recovery planning document could affect any component of the environment or any of the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy's (FSDS) goals and targets.

Recovery planning is intended to benefit species at risk and biodiversity in general. However, it is recognized that strategies may also inadvertently lead to environmental effects beyond the intended benefits. The planning process based on national guidelines directly incorporates consideration of all environmental effects, with a particular focus on possible impacts upon non-target species or habitats. The results of the SEA are incorporated directly into the strategy itself, but are also summarized below in this statement.

This federal recovery strategy will clearly benefit the environment by promoting the recovery of the Jefferson Salamander and by protecting and enhancing breeding habitat for other co-occurring amphibian species. Government-supported strategies presented in the Government Response Statement will have a positive impact on other wildlife species occupying Carolinian forest, as well as protecting the remnant forest itself. Efforts to protect habitat, to identify potential approaches to mitigate environmental and cultural stressors, and to understand the sensitivity of ponds and vernal pools to changes in the quantity and quality of water will inevitably benefit species found in association with the Jefferson Salamander. The potential for the strategy to inadvertently lead to adverse effects on other species was considered and no adverse effects from potential mitigation activities were identified.

The SEA concluded that this strategy will clearly benefit the environment and will not entail any significant adverse effects.

Bi, K. and J. P. Bogart. 2010. Time and time again: unisexual salamanders (genus Ambystoma) are the oldest unisexual vertebrates. BMC Evolutionary Biology 10(1): 238.

Bogart, J. P. 2003. Genetics and systematics of hybrid species. In: Sever, D.M. (ed). Reproductive biology and phylogeny of Urodela, Vol. 1. M/s Science, Enfield, New Hampshire, pp 109-134.

Bogart, J. P. and M. W. Klemens. 1997. Hybrids and genetic interactions of mole salamanders (Ambystoma jeffersonianum and A. laterale) (Amphibia, Caudata) in New York and New England. American Museum Novitates 3218: 78.

Bogart, J. P. and M. W. Klemens. 2008. Additional distributional records of Ambystoma laterale, A. jeffersonianum (Amphibia: Caudata) and their unisexual kleptogens in northeastern North America. American Museum Novitates 3627: 1-58

COSEWIC. 2010. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Jefferson Salamander Ambystoma jeffersonianum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. xi + 38pp.

Faccio, S.D. 2003. Post breeding emigration and habitat use by Jefferson and Spotted Salamanders in Vermont. Journal of Herpetology 37:479-489

Government of Canada. 2009. Species at Risk Act Policies, Overarching Policy Framework [Draft]. Species at Risk Act Policy and Guidelines Series. Environment Canada. Ottawa. 38pp.

Jefferson Salamander Recovery Team. 2010. Recovery strategy for the Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 29 pp.

NatureServe. 2012a. NatureServe Explorer: an online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Website: (http://www.natureserve.org/explorer) [accessed 25 April 2014].

NatureServe. 2012b. NatureServe Conservation Status. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Website: (http://www.natureserve.org/explorer/ranking.htm#globalstatus) [accessed 25 April 2014].

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR). 2008. Home range, migratory movements and habitat use of Jefferson Salamander complex in Southern Ontario as determined by radio telemetry. Working title; unpublished data.

Semlitsch, R.D. 1998. Biological delineation of terrestrial buffer zones for pond-breeding salamanders. Conservation Biology 12(5):1113-1119.

Thompson, E. L., J. E. Gates, and G.S. Taylor. 1980. Distribution and breeding habitat selection of the Jefferson Salamander, Ambystoma jeffersonianum, in Maryland. Journal of Herpetology 14: 113-120.

Weller, W. F. 1980. Migration of the salamanders Ambystoma jeffersonianum (Green) and A. platineum (Cope) to and from a spring breeding pond, and the growth, development and metamorphosis of their young. M.Sc Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario. 248pp.

Rank Definitions (NatureServe 2012b)

| Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) S-rank |

Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) State/Province |

|---|---|

| S1 (Imperilled) | Ontario, Illinois, Vermont |

| S2S3 (Imperiled-Vulnerable) | Massachusetts, New Hampshire |

| S3 (Vulnerable) | Connecticut, Maryland, New Jersey, West Virginia |

| S3S4 (Vulnerable-Apparently Secure) | Pennsylvania |

| S4 (Apparently Secure) | Indiana, Kentucky, New York, Virginia |

| SNR (Unranked) | Ohio |

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA, 2007) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

Under the ESA, 2007, a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA, 2007 outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There is a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA, 2007. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources Species at Risk webpage.

Jefferson Salamander Recovery Team. 2010. Recovery strategy for the Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 29 pp.

Cover illustration:Leo Kenney, Vernal Pool Association

© Queen's Printer for Ontario, 2010

ISBN 978-1-4435-0904-6 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

The recovery strategy was developed by the Jefferson Salamander Recovery Team.

Members of the recovery team wish to acknowledge people who have submitted salamander eggs to the University of Guelph for identification, in particular Mary Gartshore, Bill Lamond, Al Sandilands and Craig Campbell. We would also like to thank David Servage, Lesley Lowcock and Alison Taylor, who made significant contributions to our understanding of the complex Ambystoma laterale (Blue-Spotted Salamander)–jeffersonianum complex during their tenures in the Master of Science program at the University of Guelph. Karine Bériault and Cadhla Ramsden's research on habitat requirements and non-lethal sampling methods has been invaluable. Leslie Rye and Wayne Weller accumulated the information and produced the status report for the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). Special mention is extended to Brenda Van Ryswyk and Albert Garofalo, who collected much of the data for the radio-telemetry studies, and to Pete Lyons, who provided property access. The recovery team would also like to thank Fiona Reid and Don Scallen for their help with locating new populations of this species. Sarah Weber is acknowledged for her thorough copy edit of this strategy.

The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources has led the development of this recovery strategy for the Jefferson Salamander in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA 2007). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario

This recovery strategy outlines the objectives and strategies necessary for the protection and recovery of Canadian populations of the Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum). The strategy was developed with the goal of ensuring that existing threats to populations and habitat of this species are sufficiently removed to allow for long-term persistence and expansion of the Jefferson Salamander within its existing Canadian range. The strategy is based on a comprehensive review of current and historical population census data and research, in addition to genetic analyses that provide accurate identifications of this salamander species and members of the Ambystoma laterale (Blue-Spotted Salamander)–jeffersonianum complex.

Jefferson Salamander populations have a distinctive genetic evolutionary history. Ontario populations coexist with unisexual individuals that are mostly polyploids with a predominance of Jefferson Salamander chromosomes, and which together are referred to as members of the A. laterale–jeffersonianium complex. Jefferson Salamander and polyploids use the same habitat, and the polyploids are reproductively dependant on the Jefferson Salamander. That is, the presence of jeffersonianum-dominated polyploid eggs necessarily means that Jefferson Salamander is present as a sperm donor for those unisexual polyploids. For these reasons, the recommendations in this recovery strategy relating to the identification, mapping and protection of habitat apply to both Jefferson Salamander and jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids. The apparent absence or lack of documentation of a Jefferson Salamander individual is often the result of naturally low relative abundance and/or limited search effort (Bogart and Klemens 2008).

Major threats to the Jefferson Salamander in Ontario include habitat loss, habitat fragmentation and degradation/alteration, road mortality, impairment of wetland/hydrologic function and the introduction of fish to breeding ponds.

The conservation biology of the Jefferson Salamander is well known in comparison to that of other species at risk in Ontario. This recovery strategy provides the scientific basis with which to establish habitat protection guidelines and make recommendations to protect this species in Ontario. Toward this end, this recovery strategy also outlines and prioritizes recovery approaches and programs. Because known Jefferson Salamander populations exist in areas that are presently under development pressure, there is an urgent need to implement the recovery approaches and to communicate the recovery goals to municipalities, developers and other stakeholders where conflicts exist or are anticipated.

It is recommended that the habitat regulation for the Jefferson Salamander include:

- all wetlands or wetland features that provide suitable breeding conditions where the Jefferson Salamander and jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids occur;

- terrestrial habitat areas within 300 metres of the edge of breeding ponds that provide conditions required for foraging, dispersal, migration and hibernation; and

- corridors that provide contiguous connections between breeding locations (up to a maximum distance of 1 kilometre).

Any newly discovered breeding locations and associated terrestrial habitat, as well as extirpated and historical locations where suitable habitat remains, should also be included within the regulation.

Common Name: Jefferson Salamander

Scientific Name: Ambystoma jeffersonianum

SARO List Classification: Threatened

SARO List History: Threatened (2004)

COSEWIC Assessment History: Threatened (2000)

SARA Schedule 1: Threatened (June 5, 2003)

Conservation Status Rankings: GRANK: G4; NRANK: N2; SRANK: S2

The glossary provides definitions for the abbreviations above.

The Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) is a relatively large grey to brownish grey salamander (snout to vent length: 65–96 millimetres [mm]). Bishop (1947) described egg masses of this species. The eggs are incorporated in gelatinous masses that are attached to sticks and species stems. Each egg mass contains 16 to 40 large (2.0–2.5 mm) eggs, which contain a black or dark brown embryo enclosed in a distinct envelope. A loose, watery layer of protective gel surrounds the eggs. The dark melanin pigment and the gel covering (and any algae in it), along with dissolved organic matter in the water, protect the developing embryos from damage through exposure to ultraviolet B radiation (Licht 2003). Individual females lay several such egg masses, which contain more than 200 eggs, depending on the size of the female.

Breeding success varies from year to year, depending on spring weather and water-level conditions. However, because Jefferson Salamanders are long lived (up to 30 years) populations can be resilient to such variable reproductive output. Eggs complete their development in two to four weeks (depending primarily on water temperature). Hatchlings are 10 to 14 millimetres in total length. The transformation from larvae to adults normally occurs in July and August, when juveniles move out of the pond and seek shelter in the forest litter. The larval stage varies in duration and can extend into early September.

The unusual reproductive biology and genetics of the Jefferson Salamander have presented a number of challenges in formulating recovery recommendations. The summary below is intended to explain the main aspects of the A. laterale (Blue-Spotted Salamander)–jeffersonianum complex.

Jefferson Salamander populations normally coexist with unisexual individuals that are mostly polyploid with a predominance of Jefferson Salamander chromosomes; together they constitute the A. laterale–jeffersonianum complex. The presence of eggs of jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids necessarily and absolutely indicates the presence of a breeding pure Jefferson Salamander, which is required as a sperm donor to initiate egg development of jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids (Bogart and Klemens 1997, 2008, Rye and Weller 2000, OMNR 2008 unpublished data). In Ontario, the correspondence between pure Jefferson Salamanders and jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids is absolute, as is the case in New England and New York (Bogart and Klemens 1997, 2008). Pure Jefferson Salamanders and jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids cannot be separated by habitat or in many cases by morphology. Therefore, genetic analysis is often required to distinguish pure Jefferson Salamanders from polyploids, and particularly to distinguish pure female Jefferson Salamanders. Blue-spotted Salamanders (Ambystoma laterale) and laterale-dominated polyploids are the other members of the complex. Polyploids dominated by the Blue-spotted Salamander are not indicative of Jefferson Salamanders. Polyploid members of the complex are generally triploid, but tetraploid and pentaploid individuals have also been documented (Bogart 2003).

Contrary to earlier theories, there is no evidence of past or present hybridization among the members of the A. laterale–jeffersonianium complex (Bogart 2003). Mitochondrial DNA from polyploid females predates that of the Jefferson Salamander and Blue-spotted Salamander (Bogart et al. 2007) and has been matched with that of a Kentucky population of the Streamside Salamander (Ambystoma barbouri) (Bogart 2003). The genetic mixing that occurs within the polyploid component of the complex is attributed to an unusual reproductive strategy (gynogenesis) whereby polyploid females lay mostly unreduced eggs (eggs whose number of sets of chromosomes is equivalent to that of the parent's somatic cells), and where sperm from a diploid male is required solely to initiate egg development (Elinson et al. 1992). Occasionally, reduced eggs (eggs with only one set of chromosomes) will be present in an egg mass, and genetic material from sperm can be incorporated into the embryos (Bogart 2003).

Jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids demonstrate the same ecology and use of habitat as pure Jefferson Salamanders (Bériault 2005, OMNR 2008). However, jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids are much more abundant, normally comprising 90 to 95 percent of local populations (Bogart and Klemens 2008, 1997, OMNR 2008 unpublished data). Therefore, many search efforts focused on finding Jefferson Salamanders using a random sampling of the population would probably encounter only jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids.

Because the Jefferson Salamander and jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids cannot be separated by habitat, and because the perpetuation of the polyploid component of the complex is dependent on the presence of the Jefferson Salamander, the recommendations in this recovery strategy relating to the identification, description, mapping and protection of habitat apply to both the Jefferson Salamander and jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids. The state of Connecticut has gone one step further and has afforded equal protection to polyploids (Bogart and Klemens 2008).

The presence of the Jefferson Salamander is critical to the survival and existence of unisexuals that make up the majority of the population complex and use Jefferson Salamander males as sperm donors.

Jefferson Salamander larvae are voracious aquatic predators that feed on moving prey such as insect larvae, small crustaceans and amphibian larvae. Adults probably are prey for wetland predators, such as snakes, rodents and birds, for example, the Red-shouldered Hawk (Buteo lineatus). The Jefferson Salamander plays an important role in channeling nutrients between the aquatic environment and the upland wooded environment and is an indicator species of high-quality vernal pools.

The Canadian range of the Jefferson Salamander is restricted to southern Ontario, particularly along the Niagara Escarpment World Biosphere Reserve. In the United States, the species ranges from New York and New England south and southwestward to Indiana, Kentucky, West Virginia and Virginia. An ecological isolate occurs in east-central Illinois (Petranka 1998) (figure 1). For much of this range, genetic data are unavailable, so the continental distribution of pure Jefferson Salamanders and jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids is uncertain (Bogart and Klemens 1997).

The current global conservation status rank for the Jefferson Salamander was assigned by the Association for Biodiversity Information (ABI) (NatureServe 2008). Its ranking for the Jefferson Salamander is G4, a level of ranking assigned to species with greater than 100 site occurrences and greater than 10,000 individuals, giving the species an apparently secure ranking globally. NatureServe also applies conservation status ranks at the national (N) and subnational (S) (i.e., provinces or states) levels. table 1 summarizes the NatureServe rankings for the Canadian and U.S. populations. The species has been designated as imperilled (S2) in Ontario, Illinois and Vermont and is considered to be apparently secure (S4) in only 5 of the 14 states where it is found. Notably, the species is also listed as threatened in Ontario under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA 2007) and in Canada under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA).

| Jurisdiction | Conservation Status Rank |

|---|---|

| Global | G4 |

| Canada | N2 |

| Ontario | S2 |

| United States | N4 |

| Connecticut | S3 |

| Illinois | S2 |

| Indiana | S4 |

| Kentucky | S4 |

| Maryland | S3 |

| Massachusetts | S2S3 |

| New Hampshire | S2S3 |

| New Jersey | S3 |

| New York | S4 |

| Ohio | SNR |

| Pennsylvania | S4 |

| Vermont | S2 |

| Virginia | S4 |

| West Virginia | S3 |

Legend:

N2/S2 – Imperilled (i.e., extremely rare or especially vulnerable)

S3 – Vulnerable to extirpation or extinction (i.e., rare and uncommon)

G4/N4/S4 – Apparently Secure (i.e., uncommon but not rare)

SNR – Unranked

Note: This map is based on Element Occurrence (EO) records, which represent specific locality data that are developed and maintained by individual provincial and state natural heritage programs. The Canadian distribution is shown as individual occurrences and the U.S. distribution is shown as the watersheds where the occurrences are found.

Long description for Figure 1 - Part 2

The distribution of the Jefferson Salamander in Canada as of October 2008 is based on approximately 328 known breeding ponds representing approximately 27 geographically discrete populations. A geographically discrete population is one that is separated or isolated from other populations by gaps in habitat that limit or prevent gene flow. Distribution data reflect both extant and historic occurrences.

Figure 2 provides the most current locality information for the species. The information is based on a database of all Ontario locations that were compiled by the recovery team and housed at the Natural Heritage Information Centre (NHIC).

The NHIC (2003) has assigned the species a rank of S2 (i.e., very rare in Ontario; usually between 5 and 20 element occurrences in the province, or few remaining hectares, or with many individuals in fewer occurrences; often susceptible to extirpation). The S-rank applies only to pure Jefferson Salamanders, which, by virtue of their very low relative abundance within the complex, means they are exceedingly rare.

In Ontario, known extant populations of the Jefferson Salamander occur in:

- Haldimand, Norfolk, Wellington, Brant, Grey and Elgin counties;

- forested habitat along the Niagara Escarpment from the Hamilton area to Orangeville;

- isolated localities in Halton, Peel, Waterloo, York and Niagara regions;

- Dufferin County east of the Niagara Escarpment.

A population in Wellington County, south of Guelph, is probably extirpated. Jefferson Salamanders were last observed at that site in April 1989 (Bogart unpublished data) and the breeding pond was dry in successive years (1990–93). Historically, the Jefferson Salamander was probably much more widely distributed throughout southwestern and south-central Ontario before the clearing of forests for agriculture.

Populations of the Jefferson Salamander in Canada are situated at the northern limit of the species' North American range. The Canadian populations probably represent a maximum of 1 to 3 percent of the estimated North American population, based on relative ranges (Rye and Weller 2000) (figure 1).

Long description for Figure 2 - Part 2

The Jefferson Salamander was first recognized to occur in Canada by Weller and Sprules in 1976. The present knowledge of this species indicates that the current isolated populations are remnants of what was once a more extensive (i.e., continuous) range throughout southern Ontario. Fragmentation and loss of habitat have led to the isolation of these populations. In the part of the province located south and east of the Canadian Shield, over 70 percent of the original woodlands have been lost since European settlement (Riley and Mohr 1994). Habitats have been further lost and fragmented as a result of large-scale agriculture, urbanization, road networks and resource development activities, such as aggregate extraction.

As noted above, the Canadian range of this species comprises approximately 27 known populations in Ontario. One breeding pond does not necessarily represent a population; several or many breeding ponds within an area may support a discrete population. Populations are represented by one or more breeding ponds within an area of contiguous suitable habitat.

Available population census information does not permit an assessment of global abundance trends for this species. Its current global conservation status rank is G4 (NatureServe 2008), which indicates that the species is apparently secure within its range. In Ontario, however, threats to the Jefferson Salamander (see section 1.6) are well known, and cumulative loss and impairment of habitat continue.

Temporal trends for this species are not readily available because of the challenges in identifying the Jefferson Salamander and the unisexuals. As stated earlier, jeffersonianum-dominated polyploids occur at much greater relative abundance and normally comprise 90 to 95 percent of local populations (Bogart and Klemens 1997, 2008, OMNR 2008 unpublished data). This means that pure Jefferson Salamanders represent only 5 to 10 percent of the relative abundance of the population (Bogart and Klemens 2008).

Normally, estimations of distribution of vertebrate species may be obtained from museum records and voucher specimens. Such historical identifications of the Jefferson Salamander, as well as available museum records, are, however, not necessarily accurate. Bishop (1947), in his classic book on North American salamanders, lumped all presently recognized members of the complex (Blue-spotted Salamander, Jefferson Salamander and all unisexuals) in a single species, the Jefferson Salamander. Until 1964, most museum curators adhered to Bishop's nomenclature without the benefit of genetic confirmation. It is now understood that distinguishing between most individuals of the complex that are catalogued in major museum collections is not possible.

Uzzell (1964) tried to establish ranges for the Jefferson Salamander by sorting the males into Blue-spotted Salamander and Jefferson Salamander and by using blood-cell size to distinguish diploid and triploid females. Uzzell's ranges for the Jefferson Salamanderwere based on very few individuals (8 from Massachusetts, 1 from New Jersey, 37 from New York and 1 from Vermont). Bogart and Klemens (1997) provided a more accurate range of the Jefferson Salamander in New York and New England through the isozyme screening of 1,006 individuals from 106 sites. That large sample identified only 66 pure Jefferson Salamander individuals (6.59%). The global range (figure 1) is based on limited data, and occurrences in many regions still require genetic confirmation.

Jefferson Salamander individuals occur in all of the populations shown in figure 2 (Bogart 1982, Bogart and Cook 1991, Lamond 1994, Bogart unpublished information), but some of these localities have not been revisited for more than 10 years.

Despite difficulties in genetic identification, the available population data show a declining trend (Rye and Weller 2000).

During the first spring rains in March and April, adult Jefferson Salamanders migrate overland at night to breeding ponds (e.g., vernal pools) where mating and oviposition take place.The species uses a range of wetland types for breeding. Breeding ponds are generally vernal pools that are fed by either groundwater (e.g., springs), snowmelt or surfacewater. These types of ponds normally dry in mid to late summer. Other types of wetlands used for breeding may have permanent or semi-permanent water. The ponds are generally located within a woodland or in proximity to a woodland. Jefferson Salamander individuals demonstrate strong pond fidelity, returning to the same pond each year to breed.

Within breeding ponds the Jefferson Salamander requires low shrubs, twigs, fallen tree branches, submerged riparian vegetation or emergent vegetation to which to attach egg masses.

Research has shown that the depth of the water, water temperature, pH, and other water-chemistry and water-quality parameters are not good predictors of the species' use of breeding ponds (Bériault 2005). In central Pennsylvania, one of the few regions in which unisexuals do not coexist with the Jefferson Salamander,embryonic (larval) mortality was high in ponds with a pH below 4.5. Because the Jefferson Salamander larvae are not particularly susceptible to relatively low pH (K. Beriault pers. comm.), mortality was probably affected by the availability of prey (Sadinski and Dunson 1992).

Food must be present in the breeding ponds. Known aquatic prey includes small aquatic invertebrates and amphibian larvae.

For egg masses and juvenile and adult Jefferson Salamanders to survive, breeding ponds must not contain fish that can prey on them.

The hydrologic and hydrogeologic integrity of breeding habitat must be maintained. This requires that both surfacewater hydrology and groundwater contributions are not disrupted, altered or diminished. Hydrologic assessments are required for any adjacent land use that may impact groundwater or surfacewater supporting the breeding pond.

Jefferson Salamanders use a number of terrestrial habitats during all parts of their life cycle, including during migration to and from breeding ponds, summer and fall movement and foraging, and overwintering. Most often, these salamanders are associated with deciduous or mixed woodlands. Terrestrial habitat must contain microhabitat, such as rodent burrows, rock fissures, downed woody debris, tree stumps and buttresses, leaf litter, logs, and so on. Other than during migration and breeding, Jefferson Salamanders reside in this microhabitat, overwintering in deep rock fissures and rodent burrows below the frost line. Summer burrows are horizontal and winter burrows are vertical (Faccio 2003). Jefferson Salamanders are also known to show fidelity to their terrestrial habitat (Thompson et al. 1980, OMNR 2008 unpublished data).

Prey in the terrestrial habitat includes insects, earthworms and other invertebrates.

Migratory movements occur in a variety of habitats, including woodlands, plantations, agricultural fields and early successional areas, and across roads. Radio-telemetry studies have documented that the migratory distance of adults of the jeffersonianum complex can range from hundreds of metres up to 1 kilometre from the breeding pond into surrounding habitat (Bériault 2005, Faccio 2003, Semlitsch 1998, OMNR 2008 unpublished data). Radio-telemetry studies in Ontario, however, also found that 90 percent of adults reside in suitable habitat within 300 metres of their breeding pond (Bériault 2005, OMNR 2008 unpublished data).

Factors affecting the Jefferson Salamander include the limited availability of the habitats required by the species, namely, vernal pools or fishless wetlands in woodlands for breeding, and loose, moist soils in deciduous or mixed woodlands in terrestrial sites for burrowing.

Climate change may also have an effect on the timing and success of the breeding season and on habitat.

For breeding to be successful, suitable egg attachment sites must be available, and the pond must contain an adequate amount of food. At all life stages, the Jefferson Salamander is vulnerable to predation by fish; therefore, ponds containing fish capable of preying on this species are not suitable as habitat. Many forested wetlands are connected by stream systems that provide access for fish. The lack of vernal pools and fishless wetlands in woodlands is a limiting factor.

Egg and larval mortality have been observed to be high in ponds used by most populations of the Jefferson Salamander, but dead eggs are usually attributed to the polyploids. It is believed that this is a genetic viability issue in some polyploids. Larval mortality is also high among polyploid individuals (Bogart and Licht 1986). In some years, populations can be negatively affected by ponds drying or freezing completely when adult salamanders are breeding or prior to larval transformation.

The terrestrial habitat must have an adequate humus layer, leaf litter, stumps, logs, root holes, rock fissures, an appropriate soil type and mammal burrows to support feeding, moisture retention and the avoidance of predators.

The following threats to the Jefferson Salamander are presented in order of priority.

Anthropogenic threats include development activities that result in the cumulative loss and degradation of habitat and fragmentation of breeding ponds and woodlands. Activities associated with urbanization, aggregate extraction and other resource development are the most significant threats to Jefferson Salamanders in southern Ontario. The range of this species is concentrated along the Niagara Escarpment, which is a significant aggregate extraction area.