Management Plan for the Bridle Shiner in Canada [Final] 2011: Species Information

Date of Assessment: November 2001

Common Name (population): Bridle Shiner (Méné d’herbe)

Scientific Name: Notropis bifrenatus (Cope, 1867)

COSEWIC Status: Special Concern

Reason for Designation: This species has a limited distribution in Canada and is susceptible to increased water turbidity from agricultural practices and urban development.

Canadian Occurrence: Quebec, Ontario

COSEWIC Status History: Designated Special Concern in April 1999. Status re-examined and confirmed in November 2001. Last assessment based on an existing status report with an addendum.

The Bridle Shiner (Notropis bifrenatus [Cope, 1867]) (Figure 1) is a small minnow with a slender, somewhat laterally compressed body, whose total length seldom exceeds 60 mm (Bernatchez and Giroux 2000, Holm et al. in press, Robitaille 2005). It has a small terminal mouth, and its upper jaw extends back to the lower edge of the eye (Scott and Crossman 1998, Robitaille 2005). The lower lip has little or no pigment (Holm et al. in press). The Bridle Shiner has one of the largest eyes of Canadian cyprinids, with a diameter ranging from 31.2 to 38.8% of the head length (Scott and Crossman 1998). Mature individuals have a straw-coloured dorsal surface, and silvery sides with a green-blue iridescence, as well as a silvery-white ventral surface. A black lateral band extends from the snout to the tail (Bernatchez and Giroux 2000, Holm et al. in press, Robitaille 2005). This lateral band is especially apparent on specimens preserved in alcohol or formaldehyde, but is much less obvious on live individuals. A caudal spot, confluent with the lateral band, is often present. There are usually seven principal rays on the anal fin, although Scott and Crossman (1998) recorded 32% of specimens with eight.

The Bridle Shiner lives for only two years and spawns only once, in its first or second year. It is sexually dimorphic during the breeding season which occurs in the spring and the summer. Then males turn a bright yellow or gold on the lower sides, and the first five or six pectoral rays become edged with brown. The back is darker than that of spawning females and non-breeding males. Males also develop small tubercles on the pectoral fins, head and nape. Both sexes develop yellow fins shortly before the spawning period (Harrington 1947, Scott and Crossman 1998, Holm et al. in press, Robitaille 2005). The Bridle Shiner is difficult to identify and can be easily confused with other blackline shiners (Notropis species which are superficially very similar), particularly the Blacknose Shiner (N. heterolepis) (Holm et al. in press). The lateral band of both the Bridle Shiner and the Blacknose Shiner extends onto the nose but not the chin. The Blacknose Shiner can be distinguished from the Bridle Shiner by its larger, overhanging, snout and subterminal mouth. The mouth of the Blacknose Shiner is angled at less than 45° while the Bridle Shiner’s mouth is set at a 45° angle (Letendre 1960). The Bridle Shiner can be distinguished from the Pugnose Shiner (N. anogenus) and Blackchin Shiner (N. heterodon) by the absence of black pigment on its chin (the lateral band of the Pugnose Shiner and Blackchin Shiner extends onto the nose and chin of both species). The incomplete lateral line and the insertion of the dorsal fin above or in front of the insertion of the pelvic fins also serve to distinguish adult Bridle Shiner from other similar species (Robitaille 2005).

Figure 1. Bridle Shiner (Notropis bifrenatus). Copyright Ellen Edmonson (New York State Department of Environmental Conservation).

Global Distribution – The global range of the Bridle Shiner (Figure 2) is restricted to the Atlantic drainage basin in eastern North America. It extends from eastern Lake Ontario, east to Maine and south to South Carolina (Holm et al. 2001, Robitaille 2005).

In the United States, the Bridle Shiner is found in Connecticut, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Vermont and Virginia (NatureServe 2009).

Canadian Distribution – In Canada, the Bridle Shiner’s distribution (Figure 2) extends west to the Bay of Quinte (Lake Ontario), east and north to Lake St. Paul (near Trois-Rivières), and south to Lake Memphrémagog (Holm et al. 2001, Robitaille 2005). There are no records of Bridle Shiner presence between the downstream end of the Thousand Islands region and the head of Lake St. Francis (i.e., Cornwall). However, it is possible that targeted surveys in areas of suitable habitat would detect the species in these areas.

Quebec – In Quebec, the species was first recorded in the 1940s in the areas of Montréal and Lake St. Pierre. Since then, the species has been recorded in tributaries in eight different regions of the province: Montréal, Laval, Montérégie, Estrie, Laurentides, Lanaudière, Mauricie and Centre-du-Québec (Table 1 and Figure 3). The species is typically found in the aquatic environments of the lowlands of the St. Lawrence River and in the Richelieu River area. The Bridle Shiner was also captured in the St. Lawrence River upstream of Quebec City, during surveys conducted by the St. Lawrence River Fish Monitoring Network (FMN)1 (N. La Violette, unpublished data). Details are presented below, in the Population Size, Status and Trends section.

Table 1. Historic and current Bridle Shiner sites in Quebec(1).

| Administrative Area | Waterbody (reference number for Figure 3) | Location | Year of Last Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

Laurentides |

Lake Borcoman (1) |

Ferme-Neuve |

1988 |

Lake des Journalistes (2) |

Ferme-Neuve |

1975 |

|

Lanaudière |

Lake St. Pierre archipelago (4) |

Berthierville |

2002 |

du Marais Noir creek (5) |

La Visitation-de-l’Île-Dupas |

2001 |

|

L’Assomption River (7) |

Joliette |

1987 |

|

Rivière Maskinongé (30) |

Bécancour |

1974 |

|

|

|

|

|

Mauricie and |

Lake St. Pierre (8) |

North and south shores |

2003 |

Centre-du- |

Lake St. Paul (3) |

Bécancour |

1964 |

Quebec |

|||

Montérégie, |

St. Lawrence River (6) |

Montréal-Sorel |

2001 |

Montréal and |

Lake St. Pierre archipelago (4) |

Berthier-Sorel |

2003 |

Laval |

Pot au Beurre River (9) |

Berthier-Sorel |

1997 |

Little Pot au Beurre River (10) |

Berthier-Sorel |

1995 |

|

des Ormes Creek (9) |

Berthier-Sorel |

1995 |

|

St. Lawrence River (11) |

Yamaska |

1992 |

|

St. Lawrence River (12) |

Pointe-des-Cascades |

1980 |

|

St. Lawrence River (13) |

St. Anne-de-Sorel |

1971 |

|

St. Lawrence River (14) |

St. Ignace-de-Loyola |

1971 |

|

St. Lawrence River (15) |

St. Barthélemy |

1971 |

|

St. Lawrence River (16) |

Maskinongé |

1971 |

|

des Prairies River (17) |

Pierrefonds |

1990 |

|

Richelieu River (18) |

St. Jean sur Richelieu |

1987 |

|

Richelieu River (19) |

Chambly |

1970 |

|

Richelieu River (20) |

Mont-St. Hilaire |

1970 |

|

Richelieu River (21) |

St. Roch de Richelieu |

1970 |

|

Richelieu River (22) |

St. Paul-de-l’Île-aux-Noix |

1969 |

|

Richelieu River (23) |

Henryville |

1969 |

|

Richelieu River (24) |

Iberville |

1969 |

|

Châteauguay River (25) |

St. Martine |

1983 |

|

Châteauguay River (26) |

Ormstown |

1983 |

|

Châteauguay River (27) |

Howick |

1973 |

|

Châteauguay River (28) |

Châteauguay |

1971 |

|

Lake des Deux Montagnes (29) |

Rigaud |

1975 |

|

Maskinongé River (30) |

St. Barthélemy |

1974 |

|

St. Jean Creek (not mapped) |

Châteauguay |

1974 |

|

Thousand Islands River (31) |

St. Thérèse |

1973 |

|

Thousand Islands River (32) |

St. Eustache |

1973 |

|

Thousand Islands River (33) |

Rosemère |

1973 |

|

Thousand Islands River (34) |

Fabreville |

1973 |

|

Norton Creek (27) |

Howick |

1973 |

|

Chamberry Creek (12, 40) |

Pointe-des-Cascades |

1971 |

|

Lake St. Louis (35) |

Lake Léry |

1971 |

|

Lake St. Louis (36) |

Île Perrot |

1968 |

|

Lake St. Louis (37) |

Îles de la Paix |

1965 |

|

St. Louis de Gonzague (38) |

Rivière St. Louis |

1941 |

|

Yamaska River (39) |

Yamaska |

1967 |

|

Montérégie, |

Soulanges Channel (40) |

Pointe des Cascades |

1967 |

Montréal and |

Marigot Creek (22) |

St. Paul-de-l’Île-aux-Noix |

1966 |

Laval |

Bleury River (22) |

St. Paul-de-l’Île-aux-Noix |

1966 |

La Guerre River (41) |

St. Anicet |

1965 |

|

Patenaude Creek (42) |

Cantic (place-name) |

1965 |

|

Beauvais-Davignon Creek (not mapped) |

Iberville |

1965 |

|

du Sud River (43) |

Henryville |

1965 |

|

Des Iroquois River (44) |

Talon (hamlet) |

1965 |

|

À la Raquette River (45) |

Rigaud |

1965 |

|

Beaudette River (46) |

Rivière Beaudette (St. Claire-d’Assise) |

1946 |

|

Beaudette River (47) |

Rivière Beaudette |

1946 |

|

De la Loutre Creek (48) |

Abenakis Springs (place-name) |

1945 |

|

St. François River (49) |

St. François du Lac |

1944 |

|

Brunson Creek (50) |

Dundee Centre (hamlet) |

1941 |

|

Estrie |

Lake Memphrémagog (51) |

The Narrow |

1964 |

Lake Memphrémagog (52) |

Fitch Bay |

1964 |

|

Bunker Creek (52) |

Fitch Bay |

1999 |

|

Tomkins Creek (53) |

Cedarville |

1965 |

|

Tomkins Creek (53) |

Marlington |

1999 |

|

Magog Lake (54) |

Dauville |

2007 |

(1) The information presented in Table 1 comes from the databases of the Quebec Ministère des Ressources naturelles et de la Faune and from Desroches et al. (2008).

Figure 3. Historic and current Bridle Shiner sites in Quebec. Numbers refer to waterbody locations in Table 1.

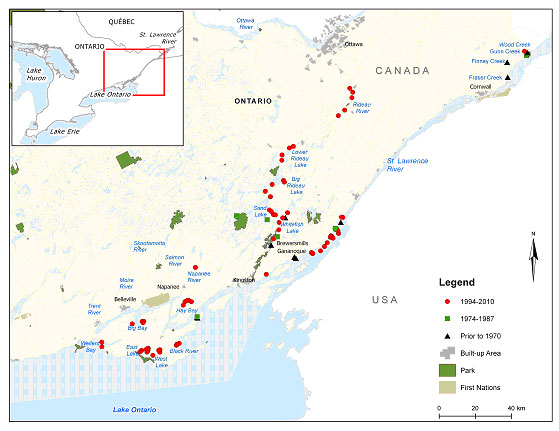

Ontario – In Ontario (Figures 4a and b), the Bridle Shiner was first captured in 1928 from the Bay of Quinte (Lake Ontario drainage) (Hubbs and Browne 1929). By 1938, after more extensive sampling, the species’ known range was extended north-east into an un-named tributary of the Rideau Canal near Brewers Mills, and eastward into the Gananoque River, the St. Lawrence River near Gananoque, and a tributary of Lake St. Francis (Holm et al. in press). Currently, the Bridle Shiner is believed to be present in the St. Lawrence River, Big Rideau Lake, Wood Creek, Jones Creek and the Napanee River. Extensive sampling by DFO in 2009 and 2010, has found Bridle Shiner in a number of new locations, including Rideau River, Upper Rideau Lake, Lower Rideau Lake, Newboro Lake, Lake Opinicon, Sand Lake, Whitefish Lake, Cranberry Lake, and Little Cranberry Lake. Specimens were also collected from various locations in the upper St. Lawrence River downstream of Gananoque. Recent sampling in the Bay of Quinte has also found them in Big Bay, Hay Bay, East Lake, West Lake, Black River, and Wellers Bay in Lake Ontario (N.E.Mandrak, DFO, unpublished data 2010). From 2008 to 2010, Raisin Region CA sampled historic Bridle Shiner locations finding them only in Finney Creek (B. Jacobs, Raisin Region Conservation Authority, pers. comm. 2011). See Table 2 for historic and current Bridle Shiner sites in Ontario.

Table 2. Historic and current Bridle Shiner sites in Ontario.

| Water body | Location |

Year of Last |

Bay of Quinte (Lake Ontario) |

Prinyer’s Cove |

1981 |

Big Bay |

2010 |

|

Hay Bay |

2010 |

|

East Lake |

2010 |

|

Black River |

2010 |

|

Gananoque River |

1938 |

|

St. Lawrence River |

Gananoque |

1938 |

Thousand Islands Region |

2005 |

|

Near Hill Island |

1999 |

|

Owen Island |

1994 |

|

Mulcaster Island |

1994 |

|

South Shore of Hill Island |

1999 |

|

Hill Island, across from Club Island |

1994 |

|

North Shore of Thompson’s Bay |

2010 |

|

Mouth of Thompson’s Bay |

2009 |

|

Thompson’s Bay near 1000 Island pkwy |

2010 |

|

North side of Adelaide Island |

1974 |

|

Mallorytown Landing |

2010 |

|

Brown’s Bay |

1959 |

|

Eastview |

2009 |

|

North shore Grenadier Island |

2010 |

|

Big Rideau Lake |

Rideau Valley |

2010 |

Lower Rideau Lake |

Rideau Valley |

2010 |

Upper Rideau Lake |

Rideau Valley |

2010 |

Rideau River |

Rideau Valley |

2010 |

Whitefish Lake |

Rideau Valley |

2010 |

Sand Lake |

Rideau Valley |

2010 |

Cranberry Lake |

Rideau Valley |

2010 |

Little Cranberry Lake |

Rideau Valley |

2010 |

Newboro Lake |

Rideau Valley |

2010 |

Opinicon Lake |

Rideau Valley |

2010 |

Un-named tributary |

Brewers Mills |

1937 |

Finney Creek |

Raisin Region |

2010 |

Wood Creek |

Raisin Region |

1994 |

Gunn Creek |

Raisin Region |

1987 |

Jones Creek |

Cataraqui Region |

2009 |

Napanee River |

Strathcona |

1998 |

Morton Creek |

Cataraqui Region |

2010 |

Outlet to Leo Lake |

Cataraqui Region |

1975 |

Kingsford Lake |

Cataraqui Region |

1975 |

Hart Lake |

Cataraqui Region |

1975 |

Fraser Creek |

Raisin Region |

1961 |

Wellers Bay |

Quinte Region |

2010 |

Figure 4a. Bridle Shiner distribution in Ontario.

Figure 4b. Bridle Shiner distribution in Ontario - St. Lawrence National Islands Park sites.

Percentage of Global Distribution in Canada – Given the lack of recent sampling data, it is difficult to determine what percentage of the Bridle Shiner’s global range is in Canada. However, it probably represents only a fraction of the species’ global range (i.e., likely less than 5% of its global range is found in Canada [N.E. Mandrak, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, pers. comm. 2008]). In Canada, the Bridle Shiner is at the northern limit of its range.

Distribution Trends – The Bridle Shiner’s area of occupancy has undergone a reduction across much of its North American range. For example, it has been found recently in only one of 31 historic locations in Pennsylvania and in a small percentage of several dozen historic locations in Massachusetts (NatureServe 2009). In Canada, particularly in Quebec, the Bridle Shiner is found in regions that are highly industrialized, heavily populated or used intensively for agriculture. Consequently, it is unlikely that the species will expand its present range (Scott and Crossman 1998). The lack of sampling in recent years in certain rivers with historic records has made it difficult to evaluate distribution trends. In Quebec, FMN data indicate that the species may be declining in some areas within its present range.

Global Population Size, Status and Trends – The species has experienced a range-wide decline in abundance and in the number of sub-populations. Without human intervention, the short-term decline rate (i.e., for the next 10 to 100 years) is estimated to be 10% to 30%, while over the long-term (i.e., the next 200 years) it is estimated to be 25% to 75% (NatureServe 2009).

Several North American locations with historic Bridle Shiner records have not been recently sampled, making it difficult to determine population trends. Species identification problems can also add to the difficulty, as specimens may have been identified incorrectly. Over its entire range, the Bridle Shiner is ranked as vulnerable (G3)2 and it is considered rare (NatureServe 2009). In the United States, the Bridle Shiner is ranked as vulnerable (N3). It is considered possibly extirpated (SH) in the District of Columbia and Maryland; critically imperilled (S1) in North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Vermont; and, imperilled (S2) in Maine and Virginia. The species is undergoing status reviews in New Jersey, New York and Rhode Island (currently S4, S5 and S5 respectively) and it is believed that the S-ranks in all three states will be upgraded to either S2 or S3 (NatureServe 2009). Complete Bridle Shiner national and sub-national ranks appear in Table 3.

Table 3. Canadian and American national and sub-national conservation status ranks for the Bridle Shiner.

| Location | Conservation Status | Ranking Organization |

|---|---|---|

North America |

Vulnerable (G3) |

NatureServe |

United States |

Vulnerable (N3) |

NatureServe |

Connecticut |

S3 |

NatureServe |

Delaware |

SU |

NatureServe |

District of Columbia |

SH |

NatureServe |

Maine |

S2 |

NatureServe |

Maryland |

SH |

NatureServe |

Massachusetts |

S3 |

NatureServe |

New Hampshire |

S3 |

NatureServe |

New Jersey |

S4 |

NatureServe |

New York |

S5 |

NatureServe |

North Carolina |

S1 |

NatureServe |

Pennsylvania |

S1 |

NatureServe |

Rhode Island |

S5 |

NatureServe |

South Carolina |

SNR |

NatureServe |

Vermont |

S1? |

NatureServe |

Virginia |

S2 |

NatureServe |

Canada |

Special Concern |

Committee on the Status of |

|

Special Concern |

Species at Risk Act (SARA) |

|

Vulnerable (N3) |

NatureServe |

Ontario |

Special Concern |

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List |

Imperilled (S2) |

NatureServe |

|

Quebec |

Vulnerable |

Threatened or Vulnerable Species Act |

Vulnerable (S3) |

NatureServe |

Percentage of Global Abundance in Canada – An estimate of Bridle Shiner abundance in Canada is not available. However, given the decline in the number of sub-populations, in areas of occurrence, and in abundance of the species in the United States, it is possible that there may be a larger proportion in Canada than expected.

Significant Populations in Canada – None have been identified.

Canadian Population Size, Status and Trends – In Canada, available data indicate that the Bridle Shiner is declining in several locations. However, the species is still common in certain areas of the St. Lawrence River (e.g., Lake St. Pierre and its archipelago, Thousand Islands region) and there seems to be no indication of a reduction in abundance in these areas. The absence of recent sampling data makes it difficult to determine the population status in some Canadian locations, such as the lakes of the Rideau Canal System, Lake Memphrémagog, and Lake St. Paul (Holm et al. in press). Fraser, Gunn, Wood and Finney creeks are historic sites for Bridle Shiner that was sampled in 2008, 2009, and 2010, using the Protocol for the Detection of Fish Species at Risk in Ontario Great Lakes Area (OGLA) (Portt et al. 2008). Bridle Shiner was only found in Finney Creek in 2010 (B. Jacobs, Raisin River Conservation Authority, pers. comm. 2011).

The rate of decline of Bridle Shiner populations in Canada is unknown (Holm et al. in press). Currently the species is considered vulnerable nationally (N3), imperilled in Ontario (S2) and vulnerable in Québec (S3) (NatureServe 2009). In Québec, the Bridle Shiner is designated as a vulnerable wildlife species under the government of Québec's Act Respecting Threatened or Vulnerable Species. It has also been listed as a species of special concern under Ontario's Endangered Species Act, 2007 (Table 3).

Quebec – There are no population estimates for the Bridle Shiner in Quebec. However, abundance appears to be decreasing in certain locations, particularly in the basins of the Aux Brochets, Châteauguay, Richelieu, Yamaska and St. Francis rivers, as well as in the St. Lawrence River, in the areas of Lake St. Francis and Lake St. Louis. Although populations appear to be declining in some locations, the species remains common in some areas of the St. Lawrence River, including Lake St. Pierre and its archipelago (Robitaille 2005). Between 1995 and 2008, a large number of specimens were observed in the Montréal-Sorel reach of the St. Lawrence River as well as in Lake St. Pierre and its archipelago (Table 4).

Table 4. Bridle Shiner catch data from the St. Lawrence River in Quebec. Surveys conducted by the FMN (Data from N. La Violette and C. Côté, Quebec Ministère des Ressources naturelles et de la Faune).

| Areas | Year of Last Observation | Number1 |

|---|---|---|

Lake St. Francis |

1996 |

0 |

2004 |

0 |

|

Lake St. Louis |

1997 |

1 |

1999 |

0 |

|

2005 |

0 |

|

Montréal – Sorel reach |

2001 |

102 |

Bécancour-Batiscan reach |

1996 |

0 |

2001 |

0 |

|

2008 |

25 |

|

Lake St. Pierre archipelago |

1995 |

61 |

2003 |

221 |

|

Lake St. Pierre |

1995 |

330 |

1997 |

0 |

|

2002 |

2512 |

|

2007 |

3492 |

|

Grondines – Donnacona reach |

1997 |

0 |

2006 |

0 |

1A zero indicates that no Bridle Shiner were captured despite FMN sampling.

In Quebec, the species had not been the subject of targeted research until a rare fish species inventory was carried out in 2002 in the southern part of the L’Assomption River watershed (Lanaudière region). However, no Bridle Shiner were detected during this survey, which was conducted in the Ouareau, L’Assomption and Achigan rivers (CARA 2002). In 1987, the species was recorded in the L’Assomption River, between the Nadeau Rapids and the Gohier Dam, near Joliette (Robitaille 2005).

In Lake St. Francis, the species was confirmed in 1941 and 1945, at the mouth of the La Guerre River and in the northeast area of the lake in the late 1960s (Holm et al. in press, Robitaille 2005). There were no Bridle Shiner captured during sampling conducted by the FMN in Lake St. Francis in 1996 and 2004 (N. La Violette, unpublished data).

Similar observations were made during surveys by the FMN in Lake St. Louis where only one specimen was caught in 1997 and no specimens were caught in 1999 and 2005, although the species was formerly abundant at this area (Holm et al. in press, Robitaille 2005, N. La Violette, unpublished data).

Between 1995 and 2007, numerous Bridle Shiner were observed in the Montréal-Sorel reach of the St. Lawrence River as well as in Lake St. Pierre and its archipelago. More than 6692 specimens were collected during surveys conducted by the FMN in these locations (Holm et al. in press, Robitaille 2005, N. La Violette, unpublished data). During the first year of the FMN surveys in 1995, only Lake St. Pierre and its archipelago were sampled. In 1997, sampling was concentrated in lotic habitats. Between 1970 and 1971, 5387 specimens were also collected in the Lake St. Pierre archipelago, in the channels of Sorel and Berthier islands. During this same period, 727 specimens were collected in Lake St. Pierre (Massé and Mongeau 1974).

In the Yamaska River watershed, inventories carried out between 1963 and 1971 confirmed the presence of the Bridle Shiner in the lower reaches of the river. In 1989, 16 specimens were collected in this river; however, an electro-fishing survey carried out in 1995 did not yield any specimens (Holm et al. in press).

The Bridle Shiner was recorded in the lower part of the Châteauguay River watershed in 1968, 1975 and 1976 (Holm et al. in press). However, in 1993 and 2006, electro-fishing surveys did not yield any specimens at this location.

The Bridle Shiner was caught in the St. François River in the 1940s; however, no specimens were reported during surveys carried out at this location between 1960 and 1970, and in 1991. The species was also found in the Aux Brochets River in 1941, but no specimens were observed during a systematic survey carried out in the 1970s. However, six Bridle Shiner were collected in the spring of 1990 in Bay Missisquoi (Lake Champlain), near the mouth of the Aux Brochets River (Holm et al. in press).

The species was frequently observed in the Richelieu River in the late 1960s and thereafter, 27 specimens were collected in 1970 and six in 1989. In 1993, none were captured, and only one specimen was collected at the mouth of the river in 1995. To date, information appears to indicate that the species is still present in this river, but that numbers have been declining since the1970s (Holm et al. in press).

The presence of the Bridle Shiner in Lake St. Paul, in the Centre-du-Québec area, and in Lake Memphrémagog, in Estrie, has not been recently confirmed. Therefore, the current status of these populations remains unknown (Holm et al. in press, Robitaille 2005).

Ontario –It is difficult to estimate Bridle Shiner population sizes or trends in Ontario, as there are few records of the species and it has never been commonly encountered. The species appears to be stable in some areas but insufficient recent sampling makes it impossible to determine its status in other areas (Holm et al. in press). Population trends are also obscured by the difficulty in identifying the species (Holm et al. in press).

In 1975, the Bridle Shiner was detected in Kingsford Lake (used as a water reservoir by the Gananoque Power Company) (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources [OMNR], unpubl. data). However, it is not clear if a population remains at this location as the area has not been sampled recently. Sampling by the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), in 1994, failed to catch any Bridle Shiner in Sutherland Creek (a new location), Finney Creek and an unnamed creek near Brewers Mills (historic locations). However, the species was detected in Wood Creek, the St. Lawrence River in the Thousand Islands region and in a new location, Jones Creek (Holm et al. in press). In 1998, the species was detected in the Napanee River, near Strathcona, confirming the species’ continued presence in this drainage (Holm et al. in press).

In 1999, the Bridle Shiner was collected from a new location on the St. Lawrence River, on the southwest side of Hill Island (Holm et al. in press). Also in 1999, several locations with historic records but lacking recent capture records were re-sampled by the OMNR, including Morton Creek and Leo Lake, where historic records dated from 1967 and 1975, respectively. The Bridle Shiner was not detected at either location during the 1999 survey and effective sampling using a bag seine was limited by the soft substrates and by water depth (Dextrase 1999). It is reasonable to assume that the species is still present in Morton Creek and Leo Lake, based on habitat conditions. Further sampling using different sampling techniques, such as electro-fishing and overnight traps, should be conducted to confirm the species’ presence at these locations (Dextrase 1999). The unnamed creek near Brewers Mills where the Bridle Shiner was originally caught in 1937 is now extremely turbid and has been converted into agricultural drains along much of its reach. It is probable that the species has been extirpated from this location (Dextrase 1999). New sites with apparently suitable habitat were also sampled by the OMNR in 1999, to determine the species’ presence (Dextrase 1999). A private access beach on the east side of Gananoque Lake was sampled as it appeared to have suitable habitat and was close to other sites with recorded occurrences. Although no Bridle Shiner were caught, further sampling should be conducted using a boat to access quiet, weed-filled bays (Dextrase 1999).

Surveys conducted in 2004 at 28 sites on the St. Lawrence River and Lake St. Francis (Edwards et al. 2008) did not detect any Bridle Shiner, while surveys of the St. Lawrence Islands National Park and Big Rideau Lake in 2005 yielded ten specimens from four sites (one site in Big Rideau Lake and three sites in the St. Lawrence Islands area) (Mandrak et al. 2006). In 2007, 30 sites along the Rideau Canal between Smiths Falls, Ottawa and Lake Opinicon, were sampled in an attempt to determine the status of four species at risk, including the Bridle Shiner. However, no Bridle Shiner was detected during this survey (Mapleston et al. 2007).

Raisin Region Conservation Authority completed widespread sampling targeting Bridle Shiner at historic sites and neighbouring tributaries including Wood Creek, Gunn Creek, Fraser Creek, Finney Creek, Sutherland Creek and Raisin River from 2008 to 2010. Five specimens were collected from Finney Creek in 2010 (B. Jacobs, Raisin Region Conservation Authority, pers. comm. 2011).

Surveys performed by DFO during 2009 and 2010 found the Bridle Shiner at a number of new locations as well as confirming their presence at a couple of historic locations. In 2009, 2 Bridle Shiner specimens were collected at the mouth of Morton’s Creek, as well as 2 at the mouth of Jones Creek. 60 specimens were also collected throughout Thompson’s Bay in 2009, as well as 5 more in 2010. New locations in 2009 include upstream from Thompson’s Bay, in the St Lawrence River near Eastview Ontario, where 19 specimens were captured and 28 specimens were collected from West Lake in the Bay of Quinte, extending its known range westward in Lake Ontario.

Sampling throughout the Rideau Canal System in 2010 yielded a number of specimens from ten new locations (23 specimens from 4 sites along the Rideau River, 13 from 2 sites in Lower Rideau Lake, 8 in Upper Rideau Lake, 19 from 5 sites in Big Rideau Lake, a historic location, 1 in Newboro Lake, 9 from 3 sites in Sand Lake, 10 from 2 sites in Whitefish Lake, 19 in Cranberry Lake, and 31 from Little Cranberry Lake). Additional sampling in 2010 throughout the Bay of Quinte also found 66 Bridle Shiner in West Lake, as well as 725 at five new locations. 84 in East Lake, 22 in Black River, 27 in Big Bay, 520 in Hay Bay, as well as 72 specimens sampled from Wellers Bay in Lake Ontario, extending its known range farther westward in the Lake Ontario Drainage. (N.E. Mandrak, DFO, unpublished data, 2010).

Habitat Description – The Bridle Shiner is a warm water fish that is typically found in clear, quiet areas of streams, lagoons and lakes that have an abundance of submerged aquatic vegetation (Scott and Crossman 1998). This type of environment provides food as well as shelter from predators (Holm et al. in press, Robitaille 2005). In Canada, the Bridle Shiner has been captured in still waters of creeks and of the St. Lawrence River as well as in small lakes. The species is associated with various types of substrates, such as silt, organic debris, clay or gravel, but according to Scott and Crossman (1998), mud and sand bottoms are more typical of its habitat. The Bridle Shiner prefers clear or moderately clear waters, and is believed to avoid areas with high turbidity as it is a sight feeder, although, in Canada, it has been captured at sites where transparency was low (Secchi depths between 0.5 and 0.7 m) (Holm et al. in press). The species is tolerant of brackish water but is not acid tolerant and this will likely limit its distribution in the Canadian Shield, which is subjected to acidification (Holm et al. in press). Physical habitat at capture sites has been described as having slow-moving current, dense aquatic vegetation and substrates of organic detritus, clay, silt, gravel, rubble and rocks.

Bridle Shiner spawning habitat has been characterized as having an abundance of submerged aquatic vegetation, above which is a 15 to 50 cm layer of vegetation-free water (Harrington 1947). Spawning occurs in the water column above the vegetation. Aquatic macrophytes are essential for juvenile Bridle Shiner, which remain in amongst the vegetation in the spawning area. Larvae have cement glands enabling them to adhere to plants (Jenkins and Burkhead 1994). According to Harrington (1947), native water-milfoil (Myriophyllum sp.) stands seem to be optimal for the species during spawning.

A recent literature review (Giguère et al. 2005) to model spawning habitats of the Bridle Shiner (from early June to mid-July, for populations between Lake St. Louis and Lake St. Pierre, excluding the La Prairie basin), suggests the following spawning habitat characteristics:

- water depth ranging from 45 cm to 120 cm (excluding sites where the water depth is less than 30 cm for the period considered);

- fine substrate of clay, silt or sand;

- water velocity ranging between 0 cm/sec and 15 cm/sec; and,

- medium or high density of submerged vegetation.

The Bridle Shiner feeds on microcrustaceans, aquatic insects, detritus and living plant material. The majority of its food items are found on or above submerged aquatic plants and the species only feeds on the bottom when and where the vegetation is sparse or lacking (Harrington 1948b).

Habitat Trends in Quebec - In Québec, the intensification of agricultural activities over the last fifty years has resulted in increased stress on aquatic environments, particularly in the St. Lawrence lowlands, which encompass the majority of the Bridle Shiner's range. The Bridle Shiner has been observed in the watersheds of the L'Assomption, Richelieu, Yamaska and St. François rivers, which are some of the most polluted rivers in Québec. Water quality in these rivers is very poor, with high concentrations of nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus), pesticides, suspended matter and organic matter (MDDEP 2007). These four rivers discharge into Lake St. Pierre, an area where the Bridle Shiner is abundant. It is estimated that nearly 800 000 tons of suspended matter from agricultural lands enter this lake annually. Lake St. Pierre is also influenced by the pollutant loads from agricultural lands and the highly industrialized areas found in its periphery. For example, in 2004, Hudon and Carignan (2008) estimated that the phosphorus levels in approximately 40% of Lake St. Pierre exceeded the provincial water quality criterion to protect aquatic life in rivers (phosphorus > 30 µg P•L-1). Water quality was poorest under high discharge conditions and in shallow riparian areas under the influence of small tributaries that drained farmlands.

Habitat Trends in Ontario – In Ontario, the Lake St. Francis watershed has been impacted by agricultural development, including feedlots and dairy farms, as well as corn and mixed pasture crops. Streams in this watershed, such as Wood, Gunn, Fraser and Finney creeks, have been channelized for field drainage and contain high loads of pesticides, sediments and nutrients (Holm et al. in press). In the Ontario portion of the St. Lawrence River, there has been an increase in water clarity due to the presence of Zebra Mussels (Dreissena polymorpha), which were first discovered in the river in 1989 (Holm et al. in press). An increase in clarity would be expected to enhance aquatic macrophyte growth, which in turn may benefit Bridle Shiner. However, reports on the abundance of aquatic macrophytes have been conflicting (Holm et al. in press) and it is not clear what effect increased water clarity is having on vegetation densities. Although there are no data to support it, there are many anecdotal accounts of increased abundance of Eurasian water-milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum) in sections of the Rideau Canal over the past few years (H. Knack, Parks Canada Agency, pers. comm. 2008), which could have a potentially negative impact on the Bridle Shiner (see Section 1.5.2). In Ontario, phosphorous levels in the St. Lawrence River have declined over the last 30 years, as the result of improvements to sewage treatment, decreased levels of industrial pollution and reductions in agricultural run-off (Holm et al. in press).

The small size of the Bridle Shiner and its weak swimming ability make it an ideal forage fish (Harrington 1948a, Scott and Crossman 1998, Robitaille 2005). In the United States, it is considered to be one of the primary food sources of the Chain Pickerel (Esox niger) (Scott and Crossman 1998). Where the Bridle Shiner is abundant, it could constitute a significant food source for several fish species of interest to sport fishermen, including the Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides), Redfin Pickerel (Esox americanus) and Yellow Perch (Perca flavescens) (Holm et al. in press). In eastern Lake Ontario, the Bridle Shiner likely is, or used to be, an important food item for Black Crappie (Pomoxis nigromaculatus), Smallmouth Bass (Micropterus dolomieu), White Perch (Morone americana) and Yellow Perch (Scott and Crossman 1998).

The Bridle Shiner is one of several blackline shiners or Notropis species that are superficially similar, each having a prominent black lateral band that extends from the snout to the tail (e.g., Blackchin Shiner, Blacknose Shiner and Pugnose Shiner) (Holm et al. in press). These species are sensitive to environmental changes such as aquatic vegetation removal, turbidity, and excessive nutrient and chemical loads (Holm et al. in press). Therefore, the presence of these species in streams is a good indicator of good water quality (Scott and Crossman 1998).

The short lifespan of this species, its disjunct distribution and its limited dispersal ability, increase its sensitivity to habitat disturbance. Isolated populations are more likely to be negatively impacted by localized stress factors, which could ultimately lead to the loss of the population (Robitaille 2005). The Bridle Shiner’s specific habitat requirements, which include clear water, submersed macrophytes, adequate water depth, and slow currents, likely represents another limiting factor for the species (Holm et al. in press).

1 Two kinds of fishing gear were mainly used by the FMN: the beach seine for littoral lentic habitats and the experimental gillnet for lentic and lotic habitats, which are usually set back from the banks (La Violette et al. 2003).

2 Conservation status ranks are described in Appendix 1.

Page details

- Date modified: