Western prairie fringed orchid (Platanthera praeclara): COSEWIC assessment and status report 2016

Western Prairie Fringed Orchid

Endangered

2016

Table of contents

- Table of contents

- COSEWIC assessment summary

- COSEWIC Executive summary

- Technical summary

- Preface

- Wildlife species description and significance

- Distribution

- Habitat

- Biology

- Population sizes and trends

- Threats and limiting factors

- Threats

- 1) Natural system modification 7.0 - Calculated impact is Medium-low.

- 2) Climate change & severe weather 11.0 (Habitat alteration, droughts, storms and flooding) - Calculated impact is Medium-low.

- 3) Agriculture 2.0 - Calculated impact is Low.

- 4) Transportation and service corridors 4.0 (Roads and railroads 4.1 and utility and service lines 4.2) - Calculated impact is Low.

- 5) Invasive and other problematic species 8.0 - Calculated impact is Low.

- 6) Pollution 9.0 (Agricultural & forestry effluents 9.3) - Calculated impact is Low.

- Limiting factors

- Number of locations

- Threats

- Protection, status and ranks

- Acknowledgements and authorities contacted

- Information sources

- Biographical summary of report writers

- Collections examined

- Appendix 1. Threats assessment for Western Prairie Fringed Orchid

List of figures

- Figure 1. Western Prairie Fringed Orchid.

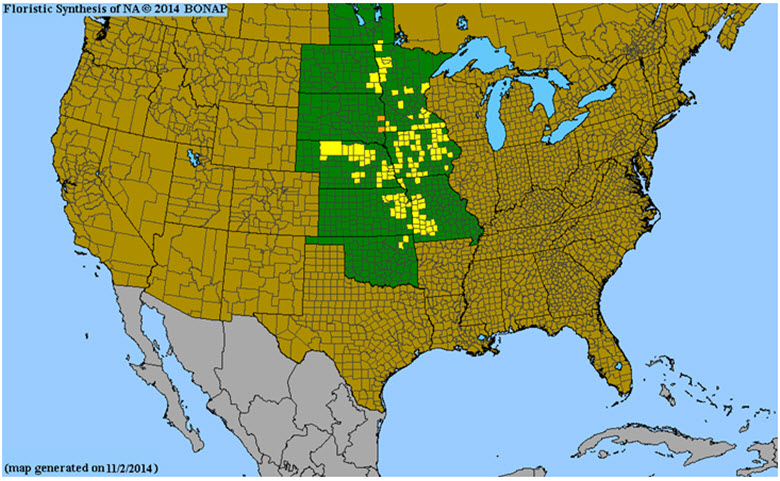

- Figure 2. Global distribution of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid based on extant subpopulations.

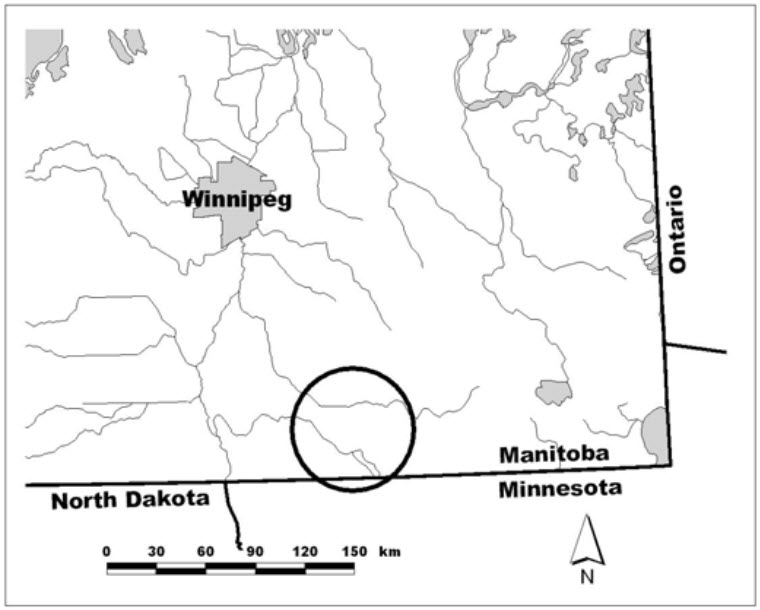

- Figure 3. Location of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid population in Manitoba.

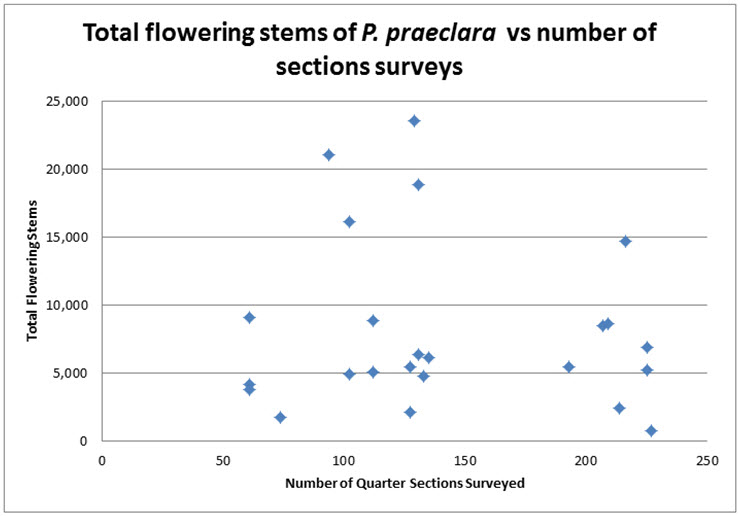

- Figure 4. Number of flowering stems of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid in the region near Vita, Manitoba compared to number of quarter-sections surveyed. (Created from Table 1)

- Figure 5. Number of flowering plants of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid in the region near Vita, Manitoba. (Created from Table 1)

- Figure 6. Western Prairie Fringed Orchid growing at the edge of a road.

List of tables

- Table 1. Number of flowering plants of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid in the region near Vita, Manitoba. (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015.)

- Table 2. Vascular plant species associated with Western Prairie Fringed Orchidin Manitoba (Punter 2000).

- Table 3. Estimated breakdown of land ownership / management for the Western Prairie Fringed Orchid (Cary Hamel pers. comm. 2016).

Document information

COSEWIC Assessment and status report on the Western Prairie Fringed Orchid Platanthera praeclara in Canada - 2016

COSEWIC

Committee on the Status

of Endangered Wildlife

in Canada

COSEPAC

Comité sur la situation

des espèces en péril

au Canada

COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows:

COSEWIC. 2016. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Western Prairie Fringed Orchid Platanthera praeclara in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xi + 47 pp.

(Species at Risk Public Registry website).

Previous report(s):

COSEWIC 2000. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the western prairie fringed orchid Platanthera praeclara in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 24 pp.

Punter, C.E. 2000. Update COSEWIC status report on the western prairie fringed orchid Platanthera praeclara in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the western prairie fringed orchid Platanthera praeclara in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-24 pp.

Collicutt, D.R. 1993. COSEWIC status report on the western prairie white fringed orchid Platanthera praeclara in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 45 pp.

Production note:

COSEWIC acknowledges Pauline K. Catling and Vivian R. Brownell for writing the status report on Western Prairie Fringed Orchid, Platanthera praeclara, in Canada, prepared with the financial support of Environment and Climate Change Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Bruce Bennett, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Vascular Plants Specialist Subcommittee.

For additional copies contact:

COSEWIC Secretariat

c/o Canadian Wildlife Service

Environment Canada

Ottawa, ON

K1A 0H3

Tel.: 819-938-4125

Fax: 819-938-3984

E-mail: COSEWIC E-mail

Website: COSEWIC

Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Platanthère blanchâtre de l’Ouest (Platanthera praeclara) au Canada.

Cover illustration/photo:

Western Prairie Fringed Orchid - Photo credit: Pauline K. Catling. This image may not be reproduced separately from this document without permission of the photographer.

COSEWIC

Assessment summary

Assessment summary - November 2016

- Common name

- Western Prairie Fringed Orchid

- Scientific name

- Platanthera praeclara

- Status

- Endangered

- Reason for designation

- This species is a globally rare orchid occurring in a restricted portion of tall-grass prairie remnants in southeastern Manitoba. It is threatened by broad-acting processes affecting habitat extent and quality, such as changes in the fire regime and modifications in soil moisture conditions due to drainage ditching and climate change.

- Occurrence

- Manitoba

- Status history

- Designated Endangered in April 1993. Status re-examined and confirmed in May 2000 and November 2016.

COSEWIC

Executive summary

Western Prairie Fringed Orchid

Platanthera praeclara

Wildlife species description and significance

Western Prairie Fringed Orchidis an herbaceous perennial with one to occasionally two hairless leafy stems about 40-90 cm tall that develop from a thick fleshy root system and tapered tuber. Plants have 4-33 relatively large, showy creamy-white flowers. Western Prairie Fringed Orchid has experienced more than a 60% decline in its original North American range and many subpopulations have fewer than 50 plants.The population of Western Prairie Fringed Orchidnear Vita in Manitoba is at the northern limit of its range and is the largest known in the world. It is estimated that Canada may support over 70% of the world population.

Distribution

The range of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid extends from southeastern Manitoba south through Minnesota, eastern North Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri and Kansas. The species is apparently extirpated from South Dakota and Oklahoma. In Canada, Western Prairie Fringed Orchid is found only in southeastern Manitoba, west of Vita in an area of approximately 100 km2.

Habitat

Western Prairie Fringed Orchid grows in wet to mesic, calcareous sandy loam soils in tall grass prairie, sedge meadows, and roadside ditches.

Biology

In the Canadian population, shoots appear above ground in late May and by late June have already formed a flower cluster. By mid-July most mature plants are in full flower with each newly opened flower lasting for several days. Non-mature plants, however, remain vegetative all year. Pollination is by sphinx moths and occurs at night. Capsules are formed by late August with plants beginning to wither by early September. Little information is available on seed germination and early development. Mycorrhizal fungi are required for successful development. Most reproduction is sexual. Some plants may remain dormant underground for one or more years relying on their mycorrhizal fungi to provide the plant with nutrition. Western Prairie Fringed Orchidforms symbiotic relationships with mycorrhizal fungi from the germinating seed to adult plant stage.

Population sizes and trends

The Canadian population, discovered in 1984, is considered to be the largest in the world. It is one of only three sites with over 1000 individuals in North America. The species is characterized by irregular flowering with mass flowering occurring in years of high precipitation and soil moisture conditions. Flowering plants greatly fluctuate in numbers from year to year with over 23,500 flowering stems counted in 2003 and only 763 observed in 2012. There have been 763 – 14,685 flowering individuals recorded in the past 10 years (2006-2015).

Threats and limiting factors

The species has a limited distribution in Canada with very little if any suitable habitat remaining outside the Vita area. The plants are sensitive to periodic climatic effects and are at risk from anthropogenic disturbance, such as conversion to cropland, overgrazing, drainage, ditch modification, invasive species, and climate change. The threats calculator indicates a high overall threat impact. Periodic fire is required in order to maintain the tall grass prairie habitat. The species appears to have a relatively low reproductive potential in that only a small portion of the flowers produce capsules. Pollination is affected by fluctuations in pollinator populations, wind and temperature.

Protection, status and ranks

Western Prairie Fringed Orchidwas first assessed and designated as Endangered by COSEWIC in 1993 and re-assessed as Endangered in 2000. It is listed as Endangered under Manitoba’s Endangered Species and Ecosystems Act and on Schedule 1 of Canada’s Species at Risk Act. A national Recovery Strategy was published by Environment Canada in 2006 that includes designation of critical habitat. The NatureServe global rank is G3 (Vulnerable), the national rank is N1 (Critically Imperilled), and the provincial rank is S1.

Western Prairie Fringed Orchidoccurs on private and provincial lands in Manitoba. Approximately 63% of the Canadian population lies within the Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve. The Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve protects over 5170 hectares (12,728 acres) of habitat for native prairie species, including the Western Prairie Fringed Orchid. Lands within the preserve are owned by the Manitoba Habitat Heritage Corporation and Nature Conservancy of Canada. Monitoring and habitat management programs for the species have been conducted within the preserve since 1992. Other sites in Manitoba receive little or no protection.

COSEWIC

Technical summary

- Scientific name:

- Platanthera praeclara

- English name:

- Western Prairie Fringed Orchid

- French name:

- Platanthère blanchâtre de l’Ouest

- Range of occurrence in Canada:

- Manitoba

Demographic information

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Generation time (usually average age of parents in the population; indicate if another method of estimating generation time indicated in the IUCN guidelines (2011) is being used) | Likely > 12 years (estimated to be 12 years until flowering). |

| Is there an observed, inferred, or projected continuing decline in number of mature individuals? | Yes – an inferred decline based on a gradual loss of suitable habitat to shrubification and agriculture. |

| Estimated percent of continuing decline in total number of mature individuals within 5 years. | Unknown due to fluctuations |

| [Observed, estimated, inferred, or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over the last [10 years, or 3 generations]. | Unknown due to fluctuations |

| Projected or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over the next 10 years. | Unknown due to fluctuations |

| [Observed, estimated, inferred, or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over any [10 years, or 3 generations] period, over a time period including both the past and the future. | Unknown due to fluctuations |

| Are the causes of the decline a. clearly reversible and b. understood and c. ceased? | a. no b. yes c. no |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of mature individuals? | Possibly, though the number of mature individuals (flowering plants) undergo extreme fluctuations, and most are believed to die following flowering – the application of extreme fluctuation does not apply to quantitative criteria as the fluctuation of mature individuals is not certain to represent changes in the total population. |

Extent and occupancy information

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Estimated extent of occurrence (EOO) | 120 km2 By convention the EOO cannot be less than the IAO. The actual EOO is (101 km2) |

| Index of area of occupancy (IAO) (number of occupied 2x2 km grid squares). |

120 km2 |

| Is the population “severely fragmented” i.e. is >50% of its total area of occupancy in habitat patches that are (a) smaller than would be required to support a viable population, and (b) separated from other habitat patches by a distance larger than the species can be expected to disperse? | No |

| Number of “locations” See Definitions and Abbreviations on site Web du COSEPAC and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term. |

There is one location in Canada (major flood, extreme drought, or disease outbreak). If land ownership is considered, the number of locations would be more than ten (possibly 21). |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in extent of occurrence? | Possibly, based on observed continued threats to the habitat on private lands and road allowances. |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in index of area of occupancy? | Possibly – one site at the southwest edge of the range has not been observed since 1998. |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in number of subpopulations? Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in number of patches? | No. The Canadian population is represented by a single subpopulation. Unknown – Numbers of flowering plants vary from year to year making actual declines uncertain. Possibly – one site has not been observed since 1998. |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in number of “locations? | No – still only one remaining location in Canada |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in [area, extent and/or quality] of habitat? | Yes, observed continued declines in habitat quality, and habitat loss on private land. |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of subpopulations? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of “locations”? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in extent of occurrence? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in index of area of occupancy? | No |

Number of mature individuals (in each subpopulation)

| Subpopulations (give plausible ranges) | N Mature individuals |

|---|---|

| Total: | 763 - 14,685 flowering individuals recorded in past 10 years (2006-2015) |

Quantitative Analysis

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Probability of extinction in the wild is at least [20% within 20 years or 5 generations, or 10% within 100 years]. | Not done |

Threats (actual or imminent, to populations or habitats, from highest impact to least)

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| The threats calculator indicates a high-low overall threat impact. | Threats include loss and degradation of habitat for the orchid and its pollinators due to agriculture (conversion to cropland, overgrazing, poorly timed haying), loss of habitat to succession due to fire prevention (encroachment by woody vegetation), extreme weather events (late spring frosts, flooding and drought) due to climate change, road allowance and ditch maintenance activities, poorly timed burns, drainage alteration, illegal collecting, invasive species, urban development, and mineral extraction. Indicated threat was lowered from high-medium to high-low because the majority of the population is on managed lands. |

Rescue effect (immigration from outside Canada)

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Status of outside population(s) most likely to provide immigrants to Canada. | Critically imperilled (S1) in 3 of the 8 states in which it occurs and Imperilled (S2) in 3 states. Possibly extirpated (SH) in South Dakota and Oklahoma. |

| Is immigration known or possible? | Possible, but unlikely |

| Would immigrants be adapted to survive in Canada? | Likely |

| Is there sufficient habitat for immigrants in Canada? | Possibly; however, habitat is very limited in Canada. |

| Are conditions deteriorating in Canada? | Yes |

| Are conditions for the outside population deteriorating? | Yes |

| Is the Canadian population considered to be a sink? | No |

| Is rescue from outside populations likely? | No |

Data sensitive species

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Is this a data sensitive species? | Yes |

Status history

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Designated Endangered in April 1993. | Status re-examined and confirmed in May 2000 and November 2016. |

Status and reasons for designation:

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Recommended Status | Endangered |

| Alpha-numeric codes | B1ab(iii)+2ab(iii) |

| Reasons for designation | This species is a globally rare orchid occurring in a restricted portion of tall-grass prairie remnants in southeastern Manitoba. It is threatened by broad-acting processes affecting habitat extent and quality, such as changes in the fire regime and modifications in soil moisture conditions due to drainage ditching and climate change. |

Applicability of criteria

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Criterion A (Decline in Total Number of Mature Individuals) | Not met. Declines do not meet thresholds. |

| Criterion B (Small Distribution Range and Decline or Fluctuation) | Meets Endangered B1ab(iii)+2ab(iii). The EOO is < 5,000 km2, the IAO is < 500 km2, there is only one location considering potential climate change impacts and a decline in the quality of habitat. Extreme fluctuations in the number of mature individuals (plants in flower) may not represent changes in the total population (i.e. including all life stages). |

| Criterion C (Small and Declining Number of Mature Individuals) | May meet Endangered C2a(ii) as there are less than 2,500 mature individuals (during fluctuation minima including recent years’ counts) and greater than or equal to 95% of all mature individuals occur in a single subpopulation. |

| Criterion D (Very Small or Restricted Population) | May meet Threatened D1 as the population is estimated to have < 1,000 mature individuals (during fluctuation minima including recent years’ counts). |

| Criterion E (Quantitative Analysis) | Not done |

Preface

The Western Prairie Fringed Orchid (Platanthera praeclara) was first recognized as a distinct species in 1986 (Sheviak and Bowles 1986) and was assessed as Endangered by COSEWIC in 1993. The Endangered status was reconfirmed in 2000.

An update status report, written by E. Punter in 2000, summarized additional research on Western Prairie Fringed Orchid since its listing. Monitoring of this species has occurred since its listing; however, much is still unknown about population trends due to extreme fluctuations in numbers of flowering individuals and the species’ potential ability to go dormant. Habitat for Western Prairie Fringed Orchid is extremely limited, and protective habitat management is required to maintain the species. For this report, additional quarter-sections outside the known Western Prairie Fringed Orchid range were visited, but there were no new discoveries.

COSEWIC history

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) was created in 1977 as a result of a recommendation at the Federal-Provincial Wildlife Conference held in 1976. It arose from the need for a single, official, scientifically sound, national listing of wildlife species at risk. In 1978, COSEWIC designated its first species and produced its first list of Canadian species at risk. Species designated at meetings of the full committee are added to the list. On June 5, 2003, the Species at Risk Act (SARA) was proclaimed. SARA establishes COSEWIC as an advisory body ensuring that species will continue to be assessed under a rigorous and independent scientific process.

COSEWIC mandate

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) assesses the national status of wild species, subspecies, varieties, or other designatable units that are considered to be at risk in Canada. Designations are made on native species for the following taxonomic groups: mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes, arthropods, molluscs, vascular plants, mosses, and lichens.

COSEWIC membership

COSEWIC comprises members from each provincial and territorial government wildlife agency, four federal entities (Canadian Wildlife Service, Parks Canada Agency, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, and the Federal Biodiversity Information Partnership, chaired by the Canadian Museum of Nature), three non-government science members and the co-chairs of the species specialist subcommittees and the Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge subcommittee. The Committee meets to consider status reports on candidate species.

Definitions (2016)

- Wildlife species

- A species, subspecies, variety, or geographically or genetically distinct population of animal, plant or other organism, other than a bacterium or virus, that is wild by nature and is either native to Canada or has extended its range into Canada without human intervention and has been present in Canada for at least 50 years.

- Extinct (X)

- A wildlife species that no longer exists.

- Extirpated (XT)

- A wildlife species no longer existing in the wild in Canada, but occurring elsewhere.

- Endangered (E)

- A wildlife species facing imminent extirpation or extinction.

- Threatened (T)

- A wildlife species likely to become endangered if limiting factors are not reversed.

-

Special concern (SC)

(Note: Formerly described as “Vulnerable” from 1990 to 1999, or “Rare” prior to 1990.) - A wildlife species that may become a threatened or an endangered species because of a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats.

-

Not at risk (NAR)

(Note: Formerly described as “Not in any category”, or “No designation required.”) - A wildlife species that has been evaluated and found to be not at risk of extinction given the current circumstances.

-

Data deficient (DD)

(Note: Formerly described as “Indeterminate” from 1994 to 1999 or “ISIBD” [insufficient scientific information on which to base a designation] prior to 1994. Definition of the [DD] category revised in 2006.) - A category that applies when the available information is insufficient (a) to resolve a species’ eligibility for assessment or (b) to permit an assessment of the species’ risk of extinction.

The Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada, provides full administrative and financial support to the COSEWIC Secretariat.

Wildlife species description and significance

Name and classification

Scientific name: Platanthera praeclara Sheviak and Bowles, Rhodora 88: 267-290. 1986.

Synonyms: Habenaria leucophaea (Nutt.) A.S. Gray var. praeclara (Sheviak & Bowles) Cronq., Cronquist, ed. 2, 864. 1991.

English common name: Western Prairie Fringed Orchid

Other common names: Western Prairie White Fringed Orchid, Western Prairie White-fringed Orchid, Western Prairie Fringed-orchid

French common name: Platanthère blanchâtre de l’Ouest

Family: Orchidaceae; orchid family

Major plant group: Monocot flowering plant

The Western Prairie Fringed Orchid was first collected in Canada on July 26, 1984 by P.M. Catling and V.R. Brownell (Catling and Brownell 1987). Before it was described as a distinct species by Sheviak and Bowles in 1986, information on the Western Prairie Fringed Orchid was previously included in the COSEWIC status report on the Eastern Prairie Fringed Orchid, Platanthera leucophaea (Brownell 1984). The two members of this species pair are similar in gross morphology, but can be distinguished by flower colour, fragrance, and size, anther morphology, column structure, petal shape, and sepal width (Sheviak and Bowles 1986). The most obvious distinguishing characteristics of the Western Prairie Fringed Orchid are its slightly larger flowers and less elongated inflorescence. Ithas divergent anther sacs with viscidia widely spaced to place pollinia on the compound eyes of moths, while in the Eastern Prairie Fringed Orchid,anther sacs are parallel with viscidia in position to attach to the tongue of moths (Sheviak and Bowles 1986).

Morphological description

Western Prairie Fringed Orchid (Figure 1) is a herbaceous perennial with thick, fleshy roots and fusiform tuber, one or rarely two stems, 38-88 cm long, glabrous; leaves glabrous, 5-7 per stem, the upper ones reduced in size and becoming bract-like; inflorescence a terminal raceme, 5-15 cm long, 5-9 cm wide, consisting of 4-33 creamy-white (to white in age) flowers (average number about 20); seeds minute, released through slits in the mature capsule (Sheviak and Bowles 1986; Smith 1993; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1996).

Long description for Figure 1

Photo of a Western Prairie Fringed Orchid plant, showing the stem, leaves (usually five to seven per stem), and creamy-white flowers (which number anywhere from 4 to 33).

Population spatial structure and variability

The single Canadian population is restricted to one area of remaining tall grass prairie habitat west and north of Vita, Manitoba. The current known distribution of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid in Canada likely represents a remnant of its previous range. There are insufficient historical records of its occurrence or previous range, but it is expected to have had a patchy distribution in the historical range of tall grass prairie in southern Manitoba (Collicutt 1993). It has been determined that there is only one large population based on the habitat-based plant element occurrence delimitation guidance (NatureServe 2004), under which occurrences are lumped into a single element occurrence (i.e., COSEWIC subpopulation) if separated by less than 1 km, or if separated by 1 to 3 km with no break in suitable habitat between them exceeding 1 km, or if separated by 3 to 10 km but connected by linear water flow and having no break in suitable habitat between them exceeding 3 km. The species is limited to wetland swales and associated mesic tall-grass prairie. Although it is patchy, there is apparently continuous suitable habitat throughout.

To date, studies of genetic diversity in Western Prairie Fringed Orchid have only included U.S. subpopulations. Two studies using isozyme markers (Pleasant and Klier 1995; Sharma 2002) found little evidence of genetic differentiation among subpopulations. More recently, Ross and Travers (2016) used six microsatellite loci to study variation in eight subpopulations in Minnesota and North Dakota. They found evidence of significant but low levels of genetic divergence among subpopulations (mean GST=0.081), and some evidence of inbreeding (average FIS=0.230). However, only subpopulations with fewer than 10 flowering individuals had FIS>0.2.

The Canadian Western Prairie Fringed Orchidpopulation is separated from the large subpopulations in the United States providing a barrier to gene flow between Canadian and American subpopulations. The closest subpopulation is 50 km south of the Tall Grass Prairie Preserve, in northwest Minnesota (Westwood and Borkowsky 2009), and is quite small.

Designatable units

There are no recognized subspecies or varieties for this species, and the Canadian population is restricted to a small area of southern Manitoba; consequently, the species is treated as a single designatable unit.

Special significance

Western Prairie Fringed Orchid is indigenous in wet to mesic tall grass prairie plant communities from Manitoba south to Wisconsin (extirpated in Oklahoma). The population of Western Prairie Fringed Orchidnear Vita in Manitoba is at the northern limit of its range and is the largest known subpopulation in the world (Punter 2000). The only other subpopulations with at least 3000 individuals occur in Minnesota and North Dakota (Punter 2000). It is estimated that Canada may support over 70% of the world population based on subpopulation sizes currently documented in the United States (NatureServe 2015).

The Western Prairie Fringed Orchid west of Vita has been a catalyst for the acquisition of tall grass prairie land for incorporation into the Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve. The Western Prairie Fringed Orchid has been a focus plant for ecotourism opportunities in the Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve promoting education and public outreach for tall grass prairie habitats.

Distribution

Global range

Western Prairie Fringed Orchid is known from 172 extant occurrences scattered throughout the western Central Lowlands and eastern Great Plains of the United States and the Interior Plains of Manitoba, Canada (NatureServe 2015). Its range extends from southeastern Manitoba south through Minnesota, eastern North Dakota, central Nebraska, Iowa, northern Missouri, and eastern Kansas (Figure 2). The eastern limit roughly corresponds to the Mississippi River (Bowles and Duxbury 1986; Watson 1989). The species is apparently extirpated from South Dakota (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1996). The locality of a specimen reported from Wyoming (Bowles 1983; Sheviak and Bowles 1986) is considered dubious and the state is excluded from the range (Bjugstad and Bjugstad 1989). The species has been apparently extirpated from Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma 2016). The last observations in Oklahoma were in 1990 and no plants have been found since, despite repeated attempts.(Buthod and Fagan pers. comm. 2016). There has also been a significant reduction in occurrences in Iowa, southeastern Kansas, Missouri, and eastern Nebraska (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1996).

Long description for Figure 2

Map of the global distribution of the Western Prairie Fringed Orchid based on 172 extant occurrences scattered throughout the western Central Lowlands and eastern Great Plains of the United States and the Interior Plains of Manitoba, Canada. Colour indicates whether the species is present and rare in a county, whether it is present and native in state, and whether the species is extirpated in a county.

Canadian range

In Canada, Western Prairie Fringed Orchid is known only from west of Vita in southeastern Manitoba (Figure 3), in an area of approximately 48 km2. There are no records of any additional occurrences in Canada despite extensive efforts to search suspected suitable habitats near the Vita population.

Long description for Figure 3

Map showing the location of the Western Prairie Fringed Orchid population in Manitoba.

Extent of occurrence and area of occupancy

For Western Prairie Fringed Orchidin Canada, the extent of occurrence (EOO) is a 101 km2 area west of Vita, Manitoba, which includes 200 quarter-sections. The biological area of occupancy was 6.7 km2 (670 ha) in 2006 (Environment Canada 2006). The index of area of occupancy (IAO) is 120 km2. Within Manitoba, Western Prairie Fringed Orchid is restricted to this limited area, and has a patchy distribution within it (though continuous within uncultivated wetland swales and associated mesic tall-grass prairie).

It is suspected that one site of a single flowering individual in the southwest edge of the area is extirpated because it has not been seen since 1998 (17 years) despite yearly monitoring. If considered extirpated, the EOO in Canada will have declined by approximately one percent (101 km2 from 111 km2).

Search effort

The species was first recorded near Vita in southeastern Manitoba in 1984 (Catling and Brownell 1987). The population census for Western Prairie Fringed Orchidis conducted by the Critical Wildlife Habitat Program technicians at the Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve. Surveys have taken place annually since 1992. The number of quarter-sections and ditches surveyed has increased steadily from 61 in 1992 to 225 in 2014 (Table 1; Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015). Since 1992, on average, 60 out of the 200 quarter-sections/ditches surveyed in a year have had flowering Western Prairie Fringed Orchid (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015). The 30-35 quarter-sections with titles held by partners of the Tall Grass Prairie Preserve are surveyed on foot with the remaining quarter-sections (~165) surveyed from the road. Owing to its height and large inflorescence of white flowers, flowering individuals of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid can be seen with binoculars from a distance of several hundred metres. Some quarter-sections surveyed only have Western Prairie Fringed Orchid in the ditch along the properties due to tilling activities occurring in the fields (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015).

The report writers visited the Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve and adjoining area in 2014 and 2015, and observed Western Prairie Fringed Orchidin both years. In 2015, the areas to the northwest and southwest of the known range were visited in order to determine if additional plants exist. Very little suitable habitat exists to the southeast and southwest due to differences in soil type and moisture, and much of the area is cultivated. Some ditches north of the Vita Drain in a Manitoba Wildlife Area appeared to contain suitable habitat; however, no flowering plants were seen. There is a previous undocumented observation from this area (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015).

| Year | Number of quarter-sections surveyeda | Number of quarter-sections with flowering orchids | # of flowering stems Ditch Total |

# of flowering stems Field Total |

# of flowering stems Total |

# of flowering stems % in Field |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 61 | 45 | 635 | 3,546 | 4,181 | 84.81 |

| 1993 | 61 | 33 | 181 | 3,613 | 3,794 | 95.23 |

| 1994 | 61 | 54 | 606 | 8,509 | 9,115 | 93.35 |

| 1995 | 74 | 37 | 301 | 1,517 | 1,818 | 83.44 |

| 1996 | 94 | 61 | 974 | 20,029 | 21,003 | 95.36 |

| 1997 | 102 | 58 | 1,378 | 14,784 | 16,162 | 91.47 |

| 1998 | 102 | 50 | 948 | 3,972 | 4,920 | 80.73 |

| 1999 | 112 | 58 | 1,394 | 7,426 | 8,820 | 84.20 |

| 2000 | 112 | 64 | 1,213 | 3,900 | 5,113 | 76.28 |

| 2001 | 127 | 52 | 593 | 1,502 | 2,095 | 71.69 |

| 2002 | 127 | 53 | 506 | 4,935 | 5,441 | 90.70 |

| 2003 | 129 | 63 | 1,044 | 22,486 | 23,530 | 95.56 |

| 2004 | 131 | 63 | 932 | 17,906 | 18,838 | 95.05 |

| 2005 | 131 | 60 | 727 | 5,643 | 6,370 | 88.59 |

| 2006 | 133 | 59 | 484 | 4,314 | 4,798 | 89.91 |

| 2007 | 135 | 72 | 1,567 | 4,561 | 6,128 | 74.43 |

| 2008 | 193 | 81 | 1,251 | 4,133 | 5,384 | 76.76 |

| 2009 | 207 | 68 | 485 | 7,981 | 8,466 | 94.27 |

| 2010 | 209 | 69 | 497 | 8,183 | 8,680 | 94.27 |

| 2011 | 216 | 82 | 1,065 | 13,620 | 14,685 | 92.75 |

| 2012 | 227 | 35 | 10 | 753 | 763 | 98.69 |

| 2013 | 214 | 70 | 268 | 2,101 | 2,369 | 88.69 |

| 2014 | 225 | 72 | 920 | 4,247 | 5,167 | 82.19 |

| 2015 | 225 | 69 | 1,044 | 5,807 | 6,851 | 84.76 |

| AVERAGE | 142.0 | 59.5 | 781.7 | 7311.2 | 8103.8 | 84.47 |

a Some quarter-sections are surveyed for ditch only as the field is used for annual agricultural crops

Habitat

The Western Prairie Fringed Orchid is restricted in Canada to the Vita area in southeastern Manitoba largely because most of the habitat in the area has been left unploughed due to the stoniness of the soils and presence of extensive wet areas. The Vita area is within the South-Eastern Lake Terrace physiographic region, a modified till and fluvial-glacial complex (Ehrlich et al. 1953). The underlying bedrock of the area is sandstone, limestone, dolomite, and shale of the Jurassic Period (Anonymous 1994). Highly calcareous till, 1-10 m thick, derived primarily from Paleozoic carbonate rock overlies the bedrock (Manitoba Mineral Resources Division 1981). The topography of the Vita area gently slopes to the northwest from an elevation of 298 m to 290 m. The surface of the glacial till has been modified by the recession of Glacial Lake Agassiz resulting in a ridge and swale topography west of Vita. The ridges and swales trend northwest to southeast.

The Western Prairie Fringed Orchidis located between the Roseau River to the south and west, Conroy Creek to the east, and Rat River Swamp and Rat River to the north. The Vita Drain, constructed in 1990 (Collicutt 1993), passing through the southern portion of the Rat River Swamp, connects Conroy Creek to the Roseau River near the village of Roseau River (20 km northwest of Vita).

Habitat requirements

The Vita area is within the Aspen-Oak Section of the Boreal Forest Region (Rowe 1959), where the deciduous elements of the boreal forest intermix with tall grass prairie. Trembling Aspen (Populus tremuloides) is the prevalent tree species, with Balsam Poplar (Populus balsamifera) in moist sites, and Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa) on better drained soils (Rowe 1959).

The soils are imperfectly drained, extremely calcareous Dark Gray Chernozemic sandy loams to loams (Canada Soil Inventory 1989) of the Garson Soil Complex (Ehrlich et al. 1953). Soils within the Garson Soil Complex are non-arable due to excessive stoniness (Ehrlich et al. 1953). The more or less stony, modified till may be covered by a thin layer up to 40 cm of fine sand of lacustrine origin. Gravel or cobble lenses are usually found between the till and sand layer. A layer of calcium carbonate accumulation is usually found within the till or between the till and sand layer. The water table is at a depth of 0-2 m (Canada Soil Inventory 1989). Depressions tend to be poorly drained (Ehrlich et al. 1953).

In the Vita area, Western Prairie Fringed Orchidis most commonly found in wet to mesic calcareous soils in open, uncultivated tall grass prairie and sedge meadows. It most often grows in relatively undisturbed grassland, but can also occur in disturbed sites, such as ditches and pastures, if they are sufficiently stabilized and in a prairie-like condition (Sheviak 1974). The habitat may be flooded for 1-2 weeks per year. Of the total flowering plant counts in ditches and fields from 1992-2014, the percent of plants in the fields ranges from 71.7% - 98.7% with an average of 90.4% (Table 1).

Generally, the water table is high during the spring to early summer. Drainage is slow after periods of heavy precipitation. Studies by Wolken (2001) found that surface soil moisture (0-4 cm) is the most important factor in determining the distribution of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid. This was also supported by studies from Sieg and Ring (1995) who found that the density of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid was correlated with surface soil moisture. Bleho et al. (2015) found that flowering rates were highest when the species experienced a combination of warm temperatures in the previous growing season followed by cool, short, snowy winters and wet springs.

In the United States, Western Prairie Fringed Orchidis usually found on unploughed, calcareous low prairies and sedge meadows. The majority of sites occur in the glaciated region on moderately well-drained to poorly drained soils (Sheyenne Delta, North Dakota), loamy and clayey glacial till (Glacial Lake Agassiz beaches, northern Minnesota), and wet-mesic to mesic soils derived from till (southern Minnesota, Iowa, eastern Nebraska, northeastern Kansas and northwestern Missouri). Western Prairie Fringed Orchidis found in seven unglaciated areas of eastern Kansas (south of the Kansas River) on mesic to wet-mesic upland prairies on level to hilly areas covered with a thin, discontinuous mantle of loess; in tall grass prairie or sedge meadows in the swales between dunes in the Nebraska; Sandhills in north-central Nebraska; and wet-mesic prairies and sedge meadows along the floodplain of the Platte River in central Nebraska (U.S. Fish and Wildlife 1996).

In Manitoba, Western Prairie Fringed Orchidfrequently occurs in wet mesic, tall grass prairie habitat dominated by Prairie Cord Grass (Spartina pectinata), Tufted Hairgrass (Deschampsia caespitosa), and Northern Reed Grass (Calamagrostis stricta ssp. inexpansa). In spring to early summer, sedges are prominent. Sedges commonly associated with Western Prairie Fringed Orchid include Brown Sedge (Carex buxbaumii) and Woolly Sedge (Carex lanuginosa) and occasionally Crawe’s Sedge (Carex crawei) and Rigid Sedge (Carex tetanica). In wetter sites, rushes (Juncus balticus and other Juncus species) and Golden Moss (Campylium chrysophyllum) are common. Low (>0.2-1 m) shrubs are scattered through the tall grass prairie including Meadow Willow (Salix petiolaris), Shrubby Cinquefoil (Dasiphora fruticosa), Swamp Birch (Betula pumila), and Dwarf Cherry (Prunus pumila). Other species commonly found in Western Prairie Fringed Orchid habitats in Manitoba are listed in Table 2. It occasionally is found on mesic sites dominated by Big Bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) and Prairie Dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis). A number of provincial, national, and North American rare plants are also associated with Western Prairie Fringed Orchid habitat. Nationally rare species include Rigid Sedge, Small White Lady’s-slipper (Cypripedium candidum), Riddell’s Goldenrod (Solidago riddellii), Great Plains Ladies’-tresses (Spiranthes magnicamporum), and Culver’s Root (Veronicastrum virginicum). Provincially rare species in Manitoba include Slender-leaved False Foxglove (Agalinis tenuifolia), Field Sedge (Carex conoidea), Northern Adder’s-tongue (Ophioglossum pusillum), and Four-flowered Loosestrife (Lysimachia quadriflora).

| no header | no header |

|---|---|

| Agalinis tenuifolia (Vahl.) Raf. | Lysimachia quadriflora Sims |

| Agoseris glauca (Pursh) Raf. | Pedicularis canadensis L. |

| Anemone canadensis L. | Pedicularis lanceolata Michx. |

| Carex sartwellii Dewey | Poa nemoralis L. |

| Comandra umbellata (L.) Nutt. | Poa palustris L. |

| Cornus stolonifera Michx. | Prunella vulgaris L. |

| Crepis runcinata (James) Torr. & Gray | Salix bebbiana Sarg. |

| Elaeagnus commutata Bernh. ex Rydb. | Salix discolor Muhl. |

| Eleocharis elliptica Kunth | Salix lutea Nutt. |

| Equisetum hyemale L. | Sanicula marilandica L. |

| Fragaria virginiana Duchesne | Senecio pauperculus Michx. |

| Galium boreale L. | Sisyrinchium montanum Greene |

| Glycyrrhiza lepidota Pursh | Spiraea alba Du Roi |

| Hierochloë odorata (L.) Beauv. | Solidago riddellii Frank ex Riddell |

| Hypoxis hirsute (L.) Colville | Thalictrum dasycarpum Fisch. & Avé-Lall. |

| Juncus longistylis Torr. | Triglochin maritimum L. |

| Koeleria macrantha (Ledeb.) J.A. Schultes | Viola nephrophylla Greene |

| Krigia biflora (Walt.) Blake | Zizia aptera (Gray) Fern. |

| Lathyrus palustris L. | blank cell |

Woody vegetation tends to encroach on tall grass prairie communities in the absence of disturbance, such as fire. Land in the Vita area, maintained for grazing and hay, is occasionally burned in the early spring. A lack of suitable disturbance, leading to a loss of habitat, is one potential threat to Western Prairie Fringed Orchid. Without suitable disturbance, succession proceeds and vegetation height and density increase to levels unfavourable for Western Prairie Fringed Orchid. The Tall Grass Prairie Preserve uses prescribed burns to prevent encroaching vegetation and maintain the prairie ecosystem (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015). Prescribed burns occur in the preserve lands approximately every 5-6 years (in the spring or fall) to reduce thatch and encroaching woody vegetation (Bleho et al. 2015; Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015). Wildfires also occur occasionally, and most recently in fall 2014 on the Agassiz trail property an estimated 30 hectares burnt. Before that a large wildfire occurred in 2012, partially burning eight quarter-sections of the preserve including areas with Western Prairie Fringed Orchid(Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015).

Habitat trends

Tall Grass Prairie is a critically endangered ecosystem in North America. Koper et al. (2010) resurveyed plant communities in 65 remnant patches in Manitoba that were previously surveyed in 1987 or 1988. They found that remnant patches are under continuous threat. Patches of surveyed prairie experienced a 37% change to other habitat types, from factors such as encroaching woody vegetation. Small patches (less than 21 ha) tend to decrease in size and quality while larger patches increase in size but still decrease in quality. Koper et al. (2010) found that the distance to edge has a stronger effect on both native and invasive species than patch size. Edge effects and encroaching vegetation could explain why smaller patches are more likely to reduce in size and decline in quality. The presence of invasive species has a negative effect on native plants indicating that invasive species may displace native species such as the Western Prairie Fringed Orchid. Many tall grass prairie species could be lost because native plants are unlikely to be self-sustaining in the competition with invasive plants (Koper et al. 2010). Immediate and continuous management is required to prevent further loss of remnant northern tall-grass prairies (Koper et al. 2010).

Biology

Life cycle and reproduction

Western Prairie Fringed Orchid is a herbaceous perennial. The root system is a fusiform tuber with radiating roots. The tuber regenerates during the growing season by forming a new tuber and perennating bud (Collicutt 1993). These new tubers can produce vegetative shoots in the following year (Collicutt 1993).

Shoots of Western Prairie Fringed Orchidappear above ground in late May. The inflorescence emerges by the third week of June, and the lower flowers are fully open on some plants (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015). By the second week of July, most of the flowers on the inflorescence have opened (Punter 2000). Flowers on plants in the Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve last for several days. Flowering stems range from 35-88 cm tall. A number of shoots remain vegetative throughout the growing season. These stems are shorter than flower stems and bear 1-3 leaves. In two permanent plots (5 m x 20 m) on adjacent quarter-sections on the Tall Grass Prairie Preserve, 90-95% of the tagged plants were vegetative (1-leaf, 2-leaf, and 3-leaf stage) and the remainder were flowering stems (4-10%) in 1994 (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015). In the Sheyenne National Grassland, North Dakota, flowers remain open for approximately seven days (Pleasants and Moe 1993) but elsewhere may last up to ten days; because flowers open sequentially, the inflorescence can produce flowers for up to three weeks (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1996). It is unknown if flowers remain receptive their entire duration.

Flowering is irregular, but plants can bloom in successive years if moisture and temperature conditions allow (Collicutt 1993). Plants have 4-33 individual flowers in an inflorescence. Flowering is dependent on conditions being favourable for successive yearly blooming (Collicutt 1993). Bleho et al. (2015) suggest that a combination of warm temperatures in the previous growing season followed by cool snowy, but short winters and wet springs benefits the species. The Manitoba population of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid has low seed capsule production (1-6% of inflorescences) compared to subpopulations in the United States (5.4-39%) (Sheviak and Bowles 1986; Pleasants 1993; Westwood and Borkowsky 2004; Borkowsky 2006). Between 1994 and 1998, Borkowsky (1998) surveyed over 1000 plants and found that 2.1% of flowering stems produced at least one capsule annually. The ellipsoid capsules release thousands of microscopic seeds, which lack endosperm, through splits in the fruit (Bowles 1983). Bleho et al. (2015) found the probability and frequency of flowering to be similar between burned and unburned sites. Annual burning is believed to be detrimental (Bleho et al. 2015). Morrison et al. (2015) suggest that early spring burns may have no effect on the orchids. Biederman et al. (2014) consider late spring burns to be harmful as the greatest fire susceptibility occurs during periods of rapid growth.

TheWestern Prairie Fringed Orchid is pollinated exclusively by nectar feeding sphinx moths (Sphingidae) (Friesen and Westwood 2013). Western Prairie Fringed Orchid is self-compatible but pollination is still required to achieve this and the species also benefits from outcrossing pollination (Sheviak and Bowles 1986). When the moths feed on nectar, the viscidium adheres to the eye or head and is removed from the flower when the pollinator leaves (Sheviak and Bowles 1986; Pleasants and Moe 1993; Westwood and Borkowsky 2004; Friesen and Westwood 2013). The pollinium protrudes from the moth’s head and pollen is transferred to the stigma when another flower is visited (Friesen and Westwood 2013). Western Prairie Fringed Orchid subpopulations in North Dakota experienced pollinaria removal from 8-33% of plants (Pleasants and Moe 1993); however, in Canada pollinaria removal ranged from 6-10% of plants (Borkowsky 2006).

The generation time of Western Prairie Fringed Orchidin Canada is uncertain, but estimates are up to 12 years until flowering (Bowles 1983). The time it takes for Western Prairie Fringed Orchid plants to emerge above ground from seed is variable but is at least two years (Davis 1995). Flowering plants in Sheyenne National Grassland, North Dakota lived for three years or less (Sieg and Ring 1995) suggesting that once they reach maturity, they do not live long. This might imply that Western Prairie Fringed Orchids have a life span of approximately 15 years. Due to having a short reproductive time within the life cycle and an 80% chance of not persisting if a plant goes into dormancy, recruitment is very dependent on seed production (Sieg and Ring 1995; Borkowsky 2006).

Sexual reproduction in Western Prairie Fringed Orchidis thought to be the principal means of recruitment of new individuals. Bowles (1983) suggested that plants are thought to be long-lived and may exist in a dormant or mycotrophic state within the soil strata for one or more years (Sheviak and Bowles 1986); however, recent studies of individuals in plots suggest otherwise. Plants that remain vegetative throughout the growing season have been observed in Manitoba and elsewhere. Vegetative plants are shorter, have 1-3 leaves, and fewer, shorter roots than flowering plants (Wolken 1995). In two permanent plots in the Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve, 90-95% of the tagged plants were vegetative in 1994 (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015). Elsewhere in the Preserve, 40-60% of the plants are estimated to be vegetative (Johnson pers. comm. in Punter 2000). In the Sheyenne National Grassland, 32-95% of the tagged plants were vegetative between 1990-1994 (Sieg and Ring 1995).

In the Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve permanent plots, plants tagged in 1994 were absent by 1999 (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015). Likewise, in the Sheyenne National Grassland, tagged plants were absent in subsequent years (Sieg and Ring 1995). Once absent in one year, Western Prairie Fringed Orchidplants have a high probability of being absent in following years (Sieg and Ring 1995; Sieg and Wolken 1999). A preliminary investigation of 10 tagged, but absent (above-ground) Western Prairie Fringed Orchidplants in 1993 and 1994 revealed no evidence of dormant orchid root tissue when excavated (Wolken 1995; Sieg and Wolken 1999). Western Prairie Fringed Orchidplants may not be as long-lived as originally thought (Sieg and Ring 1995). These findings may suggest that contrary to the previous report (Bowles 1983), Western Prairie Fringed Orchidplants do not live very long after flowering.

Pollination is required for fruit set. In the Sheyenne National Grassland, a field experiment involving hand pollination of ten plants showed that no fruit developed on flowers that received no pollination treatment. Flowers set fruit for all three pollination treatments (outcross treatment with an entire pollinium or pollen mass, outcross treatment with a partial pollinium, and self-pollination) on six plants but four plants that received pollination treatment did not set fruit (Pleasants and Moe 1993). In a study of the natural pollination of 130 plants (1033 flowers), 33% of the available pollinia were removed by pollinators and fruit set was 30%. Flowers with 1 or 2 pollinia removed were significantly more likely to set fruit than those with no pollinia removed. Plants with a higher proportion of pollinia removed had a higher proportion of flowers developing fruits. Pollination per flower was greatest during times when more open flowers are present on the inflorescence (Pleasants and Moe 1993).

Capsules of Western Prairie Fringed Orchidin Manitoba mature by late August-early September, releasing seed from early September onwards, by which time the plants have withered and turned brown (E. Punter pers. obs.). Capsule production is irregular. In one permanent plot of tagged plants monitored from 1994-1998, fruits were produced in 1996 from 13% of the flowers (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015). Zero, 81%, and 23% of flowers on tagged plants in another area in the Tall Grass Prairie Preserve produced capsules in 1988-1990 (Johnson 1989, 1991). In the same area as Johnson’s 1988-1990 survey, capsules were produced by 60% and 44% of flowers in 1994 and 1995, respectively (Dewar 1996).

Orchids have a symbiotic relationship with mycorrhizal fungi that are necessary for them to develop and survive (Currah et al. 1990). These fungi are most critical during seedling development and are necessary for successful establishment (Sharma et al. 2003a). Studies on Leafy Northern Green Orchid (Platanthera hyperborea) show that mycorrhizal fungi enter the seed through dead suspensor cells and initiated protocorm development (Richardson et al. 1992). Carbon flows from the mycorrhizal fungi through coils of fungal hyphae into the plant and in exchange the fungi consume carbohydrates produced by the plant (Harley 1959; Smith 1966, 1967; Harley and Smith 1983; Alexander 1987). Smith (1966, 1967) indicated that seedlings have a way of limiting the flow of sugars into the fungus until photosynthesis begins.

Germinating orchid seeds develop into protocorms, a mass of cells in which there is little differentiation of tissues but with a recognizable basal and apical region. The apical region gives rise to shoot and root initials, leading to the development of a juvenile plant or plantlets. In north temperate orchids, germination and early development is underground in darkness so that the protocorms are heterotrophic. Mycorrhizal fungi initially infect and occupy the basal cells of the protocorm but become restricted to the parenchyma tissue as the vascular system and shoot begin to develop. With the continued development of the shoot and chlorophyll, the plant becomes photosynthetic and somewhat autotrophic (Hadley 1982).

Little information is available about seed viability, longevity, dormancy, and germination requirements of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid. In field trials in the Tall Grass Prairie Preserve in 1992, a few seeds of Western Prairie Fringed Orchidgerminated by 45 days, and epidermal hairs formed by 108 days. One protocorm with an apical meristem developed by 108 days but its mycorrhizal status could not be determined (Zelmer 1994). Mycorrhizal colonization of seed was not always necessary to initiate germination in all of the northern temperate orchid species investigated by Zelmer (1994). However, development continued only in seeds that became colonized by mycorrhizal fungi (Zelmer et al. 1996). Roots of most orchids examined were moderately to heavily colonized by mycorrhizal fungi. These fungi represent different resources to the orchid as their nutritional strategies vary from facultative biotrophy to facultative necrotrophy to saprotrophy (Zelmer 1994). Investigation of Western Prairie Fringed Orchidroot system showed varying degrees of infection by mycorrhizal fungi within the root cortex (Zelmer 1994). Two fungi, Ceratorhiza pernacatena and Epulorhiza spp. were isolated from roots of Western Prairie Fringed Orchidfrom the Vita area (Zelmer 1994; Zelmer and Currah 1995). These two fungi may occur within the same root and same part of the root, as intact, partially digested, and mainly digested peletons (Zelmer 1994). Peletons in all stages from formation to breakdown may occur synchronously in one portion of a root but not necessarily in other parts of the root (Zelmer et al. 1996). Bjugstad-Porter (1993) isolated Rhizoctonia spp. from the roots of Western Prairie Fringed Orchidgrowing in the Sheyenne National Grassland. Seedlings and mature plants of the same species may have different endophytic mycorrhizal fungi associated with them (Zelmer et al. 1996). Studies by Alexander (2006) in Sheyenne National Grassland showed that within a year, 5% of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid seeds had increased in size and ruptured the seed coat, showing germination. Approximately 60% of the seeds were viable but stayed dormant within the first year. Seed viability varies from 9-37% and is highest in smaller subpopulations (Sharma et al. 2003). Seed longevity was also tested by Whigham et al. (2006). Seeds for orchid species from the genus Platanthera were set in the ground within seed packets for 35 months (three years). No germination was observed, but all packets contained viable seeds after that time period.

Physiology and adaptability

Mature orchids have endophytic mycorrhizal fungi in the cortical cells of roots or other absorptive structures (Currah et al. 1990). Amending soil fungal populations before transplant could increase the chances of successful transplantations (Zettler et al. 2001; Zettler and Piskin 2011). Efforts to propagate Western Prairie Fringed Orchid (Sharma et al. 2003b), and the closely related Eastern Prairie Fringed Orchid (Zettler et al. 2001), in laboratory from seed have been successful in the United States. Studies using cold stratification and that cultivated using mycorrhizal fungi of the genera Ceratorhiza and Epulorhiza that were derived from other seedlings were the most successful (Zelmer and Currah 1997; Sharma et al. 2003b). Studies on White Fringeless Orchid (Platanthera integrilabia) showed that light within the first 7 days followed by darkness promoted germination (Zettler and McInnis 1994), although this has not been tested on Western Prairie Fringed Orchid. It is still currently unknown how feasible and successful reintroductions into the wild will be for Western Prairie Fringed Orchid because ex vitro survival of Eastern Prairie Fringed Orchid has been unsuccessful (Zettler and Piskin 2011).

Most attempts to transplant Western Prairie Fringed Orchid have been unsuccessful (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015). In 1995, a number of vegetative and flowering plants of Western Prairie Fringed Orchidwere transplanted from a ditch about to be excavated to a field on Tall Grass Prairie Preserve land. These plants (56 flowering plants, 40 vegetative plants) were tagged and monitored. The number of flowering and vegetative plants decreased in successive years. By 1999, none of the tagged plants showed any above ground growth (Punter 2000). Ten Western Prairie Fringed Orchidplants were also transplanted in 1995 from the same ditch to the Rotary Prairie Nature Park in Winnipeg. Five flowering plants were observed in 1996, two flowering plants in July 1997, 1998, but none were observed in 1999 (Punter 2000). Attempts to transplant individuals to the southwest portion of the Canadian range of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid have failed, although the plants initially persisted for several years (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015).

The studies by Sharma et al. (2003a) and Zelmer et al. (1996) indicate that the mycobionts of Western Prairie Fringed Orchidmight be distributed differently in different regions and/or by age. Mycorrhizal fungi derived from seedlings are more effective at increasing in vitro success of cultured seedlings compared to fungi derived from adult Western Prairie Fringed Orchid (Sharma et al. 2003b).

Dispersal and migration

Seeds of Western Prairie Fringed Orchidare very small, consisting of a testa (seed coat) and embryo but no endosperm (Punter 2000). The testa of orchid seeds has a sculptured lipophilic surface which may aid in trapping air bubbles for dispersal in water. In seeds of some terrestrial orchid species, the presence of air trapped between the testa and embryo provides buoyancy that may aid with wind dispersal (Peterson et al. 1998). Hof et al. (1999) assumed that water was an important mode of dispersal in the Sheyenne National Grassland. In Manitoba, the mode of seed dispersal is unconfirmed but both wind and water could be agents.

Terrestrial orchids require the presence of certain fungi in the soils. Successful colonization may be limited if suitable fungi are not present. In addition, seed production may not occur unless the obligate pollinators are present (see section below).

Interspecific interactions

Fifteen species of sphinx moth, the species’ only pollinator (see Biology), co-occur with Western Prairie Fringed Orchid on the Tall Grass Prairie Preserve (Westwood and Borkowsky 2004). Only two of these, White Cherry Sphinx (Sphinx drupiferarum) and Bedstraw Hawkmoth (Hyles gallii) have been confirmed as pollinators of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid in Canada (Westwood and Borkowsky 2004; Borkowsky et al. 2011). Archemon Sphinx (Eumorpha achemon) was confirmed as a pollinator in the Sheyenne National Grasslands, North Dakota (Cuthrell and Rider 1993). Additionally Hermit Sphinx (Lintneria eremitus ) (Harris et al. 2004) and Plebian Sphinx (Paratraea plebeja) (Ashley 2001) have also been documented as pollen vectors of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid in the United States. In order to successfully receive nectar from Western Prairie Fringed Orchid, the moth’s proboscis must be longer than 30 mm, 75% of nectar spur length (Westwood et al. 2011). Based on a comparison between proboscis length and nectar spur length, White-lined Sphinx (Hyles lineata), Northern Ash Sphinx (Sphinx chersis), and Laurel Sphinx (Sphinx kalmiae) may also be pollinators of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid (Sheviak and Bowles 1986; Westwood and Borkowsky 2004). An additional non-native species, Spurge Hawkmoth (Hyles euphorbiae),has been confirmed as a pollinator in the United States (Jordan et al. 2006; Fox et al. 2013) and does occur on the Tall Grass Prairie Preserve, Manitoba (Friesen and Westwood 2013). White Cherry Sphinxand Bedstraw Hawkmothpopulations fluctuate annually, are both uncommon in Manitoba and have flight periods that have limited overlap with the flowering time of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid(Westwood and Borkowsky 2004; Westwood et al. 2011). In some years, these two pollinators have been absent from the tall grass prairie area. Their absence may be due to other factors such as low food abundance, high predator abundance, trap locality or meteorological factors (Friesen and Westwood 2013). Wind and temperature affect pollinator activity (Cruden et al. 1976; del Rio and Burquez 1986; Willmott and Burquez 1996; Friesen and Westwood 2013). Strong winds may also remove pollinaria through contact with other nearby vegetation making this a poor estimate of pollinator visitation (Borkowsky 2006).

Nectar sugar concentrations of Western Prairie Fringed Orchids decline within flowers over time (Westwood et al. 2011). Sugar concentrations are approximately 25% and similar to most other plants (Fox et al. 2015). Nectar volume increases overnight but sugar concentrations remain continuous (Westwood et al. 2011). Although nectar is a favourable reward for pollinators it also attracts nectar robbers, which chew holes in the nectar spur, and nectar thieves, that avoid assisting in pollination while stealing nectar (Fox et al. 2015). Nectar thieves discovered in North Dakota include Five-spotted Hawkmoth (Manduca quinquemaculata), Pink-spotted Hawkmoth (Agrius cingulate), European Honey Bee (Apis mellifera), Two-spotted Bumble Bee (Bombus bimaculatus), Northern Amber Bumble Bee (B. borealis), Golden Northern Bumble Bee (B. fervidus),Brown-belted Bumble Bee (B. griseocollis), Hunt’s Bumble Bee (B. huntii), Red-belted Bumble Bee(B. rufocinctus),Tri-coloured Bumble Bee(B. ternarius), and Half-black Bumble Bee (B. vagans)(Fox et al. 2015).

In Canada, adult Western Prairie Fringed Orchid had two species of mycorrhizal fungi, both belonging to the group of basidiomycetes; Ceratorhiza pernacatena and Epulorhiza calendulina (Zelmer et al. 1996). However, seedsonly yielded Epulorhiza (Zelmer et al. 1996). In Minnesota and Missouri, the genera Ceratorhiza and Epulorhiza of mycorrhizal fungi were associated with Western Prairie Fringed Orchid. Ceratorhiza is the dominant mycorrhizal fungi with Epulorhiza occurring less abundantly (Sharma et al. 2003a). This is consistent with studies on Eastern Prairie Fringed Orchid which showed Ceratorhiza to be more important in fulfilling mycotropic needs (Zettler et al. 2005).

Population sizes and trends

Sampling effort and methods

Extensive survey work for this species has been conducted over the past 24 years with annual surveys of flowering plants occurring since 1992. The population census for Western Prairie Fringed Orchidis conducted by the Critical Wildlife Habitat Program staff at the Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve (see Sampling Effort).

The report writers visited the Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve and adjoining area in 2014 and 2015, and observed Western Prairie Fringed Orchidin both years. The quarter-sections in the preserve were visited in 2015, although those on private lands were observed from the roadside.

Abundance

Within the Canadian population of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid, abundance of flowering individuals ranged from a low of 763 in 2012 to a high of 23,530 in 2003 (Table 1). There have been 763 – 14,685 flowering individuals recorded in the past 10 years (2005-2014) (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015). Within occupied sites, the number of flowering stems ranged from 1 to 2492 with the mean number of flowering individuals within a site ranging from 19 to 556 (Bleho et al. 2015). No additional subpopulations have been discovered.

The Canadian population is the largest known in the world (Punter 2000). There are only two other large subpopulations (Minnesota and North Dakota) in the northern Midwestern United States (Punter 2000). The Sheyenne National Grassland in North Dakota supports approximately 3,000 plants and the Pembina Trail Preserve in Minnesota has several thousand plants. All subpopulations in the southern half of its US range have fewer than 50 plants. The Western Prairie Fringed Orchid is no longer known to occur in 60% of the counties for which there are historical records (Harrison 1989).

Subpopulations of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid often have a patchy distribution even in the most suitable habitat. The density of Western Prairie Fringed Orchidin two permanent plots in Manitoba were 1.36 plants/m2 and 0.58 plant/m2 in 1994 (Punter 2000).

Fluctuations and trends

Mature population size (as estimated by number of flowering individuals) has undergone extreme fluctuations (i.e., changes in numbers by an order of magnitude) since monitoring began in 1992. Since 1992, flowering individuals have ranged between 763 and 23,530 (Table 1). Because there are a multitude of factors which affect number of flowers annually, numbers of flowering stems are not an absolute indicator of mature population size. Fluctuations in numbers of flowering plants may arise from natural causes (such as weather), management practices (including burn regime), uncontrollable disturbances and land use practices (Bleho et al. 2015). However, due to the short life span of flowering plants of this species (1-3 years), it is believed large fluctuations in their numbers are reflective of extreme fluctuations in numbers of mature individuals. Although the only comprehensive data are for number of flowering plants, in the Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve permanent plots, plants tagged in 1994 (vegetative and flowering) were absent by 1999 (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015). Likewise, in the Sheyenne National Grassland, tagged plants were absent in subsequent years (Sieg and Ring 1995). This indicates that numbers of flowering plants and probably numbers of vegetative plants experience fluctuations possibly in response to climatic conditions and/or pollination. Although the numbers of mature individuals undergo fluctuations by more than an order of magnitude, it is believed that the term “extreme fluctuation” applies. Guidance from the IUCN indicates that fluctuations should represent changes in the “total population” (i.e., including all life stages), rather than simply a flux of individuals between different life stages. The magnitude of fluctuations observed in the number of flowering plants of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid could be dampened by the numbers of vegetative plants in low years.

Census efficiency, which has increased since 1992, did not reveal increases in the mature population (Bleho et al. 2015).The number of quarter-sections surveyed is not correlated with the number of flowering stems indicating that the population range is well known and no additional patches have been found (Figure 4). High densities of flowering Western Prairie Fringed Orchid have been associated with high soil moisture content in the previous growing season (Sieg and Ring 1995). In Manitoba, high years (totals >10,000 flowering individuals) occurred in 1996, 1997, 2003, 2004 and 2011 (Figure 5; Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015). The highest numbers could be attributed to fires in the fall of 2000 and spring of 2001 which would reduce thatch cover and have higher flowering years in years following.

It is hard to distinguish an overall trend due to the biology of this species and because increased search efforts could bias towards an increasing or unchanging population size. The number of flowering stems of Western Prairie Fringed Orchidin Manitoba appears to spike every five-six years. The trend in Figure 5 shows that the most recent spike of 14,685 individuals in 2011 is lower than previous high abundance years which surpassed 20,000 flowering individuals. Whether or not this is indicative of a decline in population or just unfavourable conditions for flowering is uncertain. There does appear to be correlation with the occurrence of burns and wildfires within the Tall Grass Prairie Preserve with high flowering years following; however, a poorly timed wildfire paired with a drought year could have a very negative effect on the population (Bleho et al. 2015). This was the potential cause for the extremely low flowering year in 2012. There was the lowest number of flowering plants (763) in 24 years of monitoring. These trends are an estimate of mature individuals using numbers of flowering stems and the observed trends are affected by a multitude of factors (including fire and weather) (Bleho et al. 2015).

Long description for Figure 4

Chart illustrating numbers of flowering stems of the Western Prairie Fringed Orchid relative to number of quarter-sections surveyed near Vita, Manitoba.

Long description for Figure 5

Chart illustrating fluctuations in the number of flowering plants of the Western Prairie Fringed Orchid near Vita, Manitoba, from 1992 to 2015.

Rescue effect

It is unlikely that additional Western Prairie Fringed Orchid plants could become established from dispersal from subpopulations outside Canada due to limited habitat availability. Although it is believed that the seeds can be carried by wind, the closest subpopulation in the United States is approximately 50 km to the south in Lake Bronson State Park in Minnesota, and is quite small. The Sheyenne National Grassland in North Dakota which supports approximately 3,000 plants is about 400 km south, and the Pembina Trail Preserve in Minnesota which has several thousand plants is about 200 km south.

Threats and limiting factors

Threats

Possible threats were assessed using the IUCN threats calculator (Salafsky et al. 2008; Master et al. 2012; Appendix 1) and the most significant ones are summarized below. The threats are discussed below in approximate order of threat impact score. Threats with the same score are ordered as in Appendix 1. The most significant threats are ecosystem modifications that lead to habitat degradation and eventual loss and climate change. Extreme weather events due to climate change are considered to be the most serious threat over the long term. Titles in italics correspond to entries in the Threats Assessment Worksheet (Salafsky et al. 2008). The overall threat impact was calculated as High-Medium. The overall threat impact was adjusted to Medium during the threats assessment phone call – because this is a managed species with over 50% on conservation lands and because critical habitat was identified in the federal recovery strategy for 24 quarter-sections which contain Western Prairie Fringed Orchid, some of the threats may not be as high an impact in scope or severity. The Manitoba government is working on effectively protecting these lands to restrict activities that would damage or destroy the critical habitat (as listed in the recovery strategy). In addition, because the species is listed under the provincial Endangered Species Act, this also protects individuals of the species, and the habitat on which it relies, from damage.

1) Natural system modification 7.0 - Calculated impact is Medium-low.

Fire and fire suppression 7.1

Western Prairie Fringed Orchidis located in Canada in the wooded grassland (Wier 1983), an ecotone between the true prairie and boreal forest. Without disturbance such as fire, woody species invade grass-dominated plant communities resulting in the loss of shade intolerant species such as Western Prairie Fringed Orchid(Punter 2000). A lack of suitable disturbance, which enables succession to progress to taller, denser vegetation, is one of the most widespread threats in prairie ecosystems and may cause declines. Succession is a widespread and urgent threat even in protected areas.

Burning is a common tool for prairie management which can increase growth of plants and the frequency of sexual production (Collins and Wallace 1990; Pleasants 1995). A study on Western Prairie Fringed Orchid in Iowa found that in dry years the removal of litter increases drought stress and has a negative effect on plant growth and increased flower abortions (Pleasants 1995). In moist springs, burning can remove competition and increase nutrient availability in the soils which promotes orchid growth, but late spring burns might damage plants (Pleasants 1995; Biederman et al. 2014; Bohl et al. 2015). Burning after a wet year when the plants are going to flower will reduce reproduction (Pleasants 1995). Annual burning may be detrimental (Bohl et al. 2015). Sphinx moths are dependent on mixed forest for habitat (Punter 2000). Clearing and fragmentation of mixed forest resulting in the loss of food plants is a threat to the survival of these sphinx moths. Likewise, the use of fire to suppress woody vegetation may remove those plants important to the sphinx moths’ survival. Management of denser encroaching vegetation and litter buildup should consider these factors to prevent damage to the orchids and ensure reproductive success is not reduced.

Currently the lands within the Preserve are managed by prescribed burning or rotational grazing to reduce the invasion of woody vegetation and litter. The Tall Grass Prairie Preserve has a burn regime of every 4-5 years in order to reduce the threat that lack of disturbance poses to Western Prairie Fringed Orchid. Areas from half a quarter-section up to six adjacent sections may be burned at once. The factors such as precipitation are monitored in order to avoid negatively affecting the orchid population by the burning (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015). In the past eight years, spring and fall conditions have been too dry to allow for fires or too wet for them to be effective, therefore an ideal burning regime has been difficult to maintain (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015). The last time a large burn occurred was approximately four years ago when there was a large wildfire. Eight quarter sections were partially burned in 2014 (Borkowsky pers. comm. 2015).

Dams & water management/use 7.2

Surface soil moisture is the most important factor in determining the distribution of Western Prairie Fringed Orchid (Sieg and Ring 1995; Wolken 2001; Bleho et al. 2015). Drainage improvements in the Vita area that affect hydrology include deepening of ditches along roadsides and the construction of drains. Elevated roadbeds that intersect Western Prairie Fringed Orchid wetland swales impede natural near-surface groundwater flow and result in increased soil moisture and water tables on the high elevation side of the barrier, and drier conditions downhill (NCC unpublished data). The Vita Drain, running along the eastern and northern side of the Preserve, constructed in 1990, has increased surface water removal in the area (Collicutt 1993) leading to a lower water table and ultimately creating drier conditions. In years of low precipitation, a lowered water table may be detrimental to the orchid habitat and also promote the conversion of previously wet sites to agricultural uses. The 1980s were characterized by lower than average precipitation, while the precipitation rates in the 1990s were higher. The effect of the drain on the hydrology of the area has not been studied, but is expected to be adverse especially in periods when precipitation may be lower than average.

2) Climate change & severe weather 11.0 (Habitat alteration, droughts, storms and flooding) - Calculated impact is Medium-low.