Bigmouth shiner (Notropis dorsalis) COSEWIC assessment and status report: chapter 8

General Biology

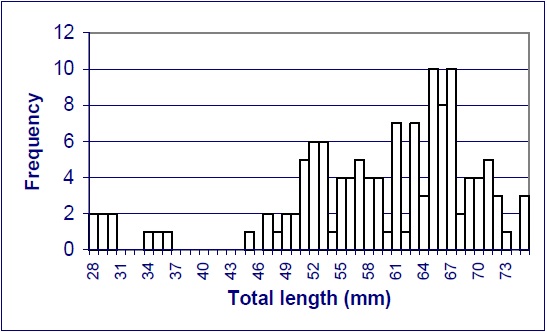

Information on the biology and life history of the bigmouth shiner is limited. Keeton (1963 in Tompkins 1987) suggests that the species is fast-growing and has a maximum life span of three years. In Ohio, Trautman (1981) found considerable variation in the size of young-of-the-year fish (28 and 50 mm), and 1+ age fish (33 and 63 mm). Adult fish ranged between 50 and 75 mm. A sample of bigmouth shiners from the Pembina River ranged in size from 65-74 mm total length (K.W. Stewart pers. comm. 2003). From a collection of 129 bigmouth shiners taken from the Cypress River in the fall of 1995, specimens ranged from 28-75 mm. No specimens could be sexed that were less than 47 mm total length, suggesting that maturation is achieved above this length. For those fish where sex could be determined, 70% were female and 30% were male (McCulloch, unpublished data). Figure 4 summarizes length-frequency distribution of the bigmouth shiners collected in the Cypress River in 1995. While most of the specimens in the collection were mature, some recruitment in the population was evident.

Nothing is known about reproductive behaviour and spawning sites of the bigmouth shiner in Manitoba (K.W. Stewart pers. comm. 2003) or elsewhere (Tompkins 1987). Becker (1983) indicates that spawning can occur between late May and early August in Wisconsin, and Starrett (1951) found that spawning occurs in late July and August in Iowa. In Illinois, Gilbert (1980) spawning occurs from May to June, while in Missouri spawning takes place in June and July (Pfleiger 1997).

Figure 4: Length-frequency Distribution of 129 Bigmouth Shiners Captured in the Fall of 1995

Fedoruk (1970) found that the bigmouth shiner in the Pembina River was often associated with the sand shiner. This association was also observed in Kansas (Cross 1967), Iowa (Harlan and Speaker 1957), Minnesota (Eddy and Underhill 1974), Pennsylvania (Cooper 1983) and Missouri (Hanson and Campbell 1963). While performing habitat studies in the Platte River in Nebraska, O’Shea et al. (1990) lumped the two species into a sand shiner-bigmouth shiner assemblage due to similarities in food and habitat preferences, and in the difficulty identifying specimens less than 25 mm.

Elsewhere in Manitoba, the bigmouth shiner is collected with the sand shiner in the Assiniboine River, but the latter can often outnumber the former by ratios of several hundred to one (Appendix 1 in McCulloch and Franzin 1996). In the Cypress River, where bigmouth shiner populations can attain some of their largest sizes, the species is frequently collected with large numbers of common shiner and creek chub. Both the longnose and western blacknose dace often also form part of this assemblage, but are represented in lower numbers (Appendix 4 in McCulloch and Franzin 1996). It should be noted that collection techniques (i.e., seine hauls) in the Cypress River often encompass several habitat types, including pools and runs. As both common shiner and creek chub tend to favour rocky or sandy pools (Page and Burr 1991), the representation of these two species in seine collections was likely achieved during that portion of the haul through pool habitat, while bigmouth shiner, longnose dace and western blacknose dace were collected while the seine was being hauled through run and riffle habitats. Stewart pers. comm., also note that western blacknose dace is commonly associated with the bigmouth shiner, as they share very similar microhabitats. Longnose dace-bigmouth shiner co-occurrences are less common, as longnose dace prefer even faster water (K.W. Stewart pers. comm. 2003). Interestingly, the sand shiner is often collected with the common shiner, creek chub, western blacknose dace, and longnose dace in the absence of the bigmouth shiner in the Souris River (Appendix 2 in McCulloch and Franzin 1996).

No information is available regarding bigmouth shiner movements in Manitoba. However, appearance of the bigmouth shiner in repeated fall collections at sites on the Cypress and Assiniboine rivers throughout the 1980s and 1990s suggests that some movement occurs, in that recolonization takes place after individuals are removed from the population after a collection event. Elsewhere, Mendelson (1975) found that the bigmouth shiner migrates upstream during fall and winter, and returns downstream in summer. Diel movements involve movement into shallow water at night, likely either to avoid terrestrial predators or to take advantage of emerging insect larvae (Mendelson 1975).

Little is known of the diet of bigmouth shiner in Manitoba. Specimens collected from the Cypress River in the fall of 1995 were feeding exclusively on water boatmen (Family Corixidae) (McCulloch, unpublished data). In Iowa, Starrett (1950) found that the bigmouth shiner increased consumption of terrestrial insects in fall in response to reductions in Ephemeroptera (mayfly) and Trichoptera (caddisfly) larvae. Starrett (1950) found that aquatic nymphs, larvae and Diptera formed a large part of the diet the remainder of the year. Elsewhere, Gilbert (1980) reported that the bigmouth shiner consumes mainly insects, but that plant material and bottom ooze was also present in the stomach. Mendelson (1975) found that benthic fauna was more prevalent in the diet than drift fauna throughout all sampling periods. The presence of caddisfly larvae (Hydropsyche spp.), along with Dicranota spp., and mite (Libertia spp.) in bigmouth shiner stomachs supports the preferred microhabitat of shallow water areas upstream from pools that Mendelson (1975) observed in Wisconsin.

Tompkins (1987) stated that taste is more important in foraging than sight. In aquaria, foraging occurred near or on the bottom, with fish swimming quickly over the substrate, inhaling sand and sorting out food through ejection out the mouth or gill opening (Pflieger 1997). The inferior and horizontal mouth is deemed consistent with bottom feeding (Hubbs 1941).

Page details

- Date modified: