A Time for Urgent Action: the 2024 report of the National Advisory Council on Poverty

On this page

- List of abbreviations

- List of tables

- List of graphs

- Acknowledgment

- Dedication

- Message from the Chairperson

- Executive summary

- Chapter 1: Setting the scene

- Chapter 2: Meeting vital needs to thrive

- Chapter 3: Improving access to benefits and delivery of services

- Chapter 4: Building strong communities and enabling equity

- Chapter 5: Recommendations

- References

- Annex A: Organizations that participated in the ongoing dialogue

- Annex B: Recommendations from previous reports of the National Advisory Council on Poverty

Alternate formats

A Time for Urgent Action: the 2024 report of the National Advisory Council on Poverty [PDF - 3,38 MB]

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

List of abbreviations

- 2SLGBTQI+

- Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and people who identify as part of sexual and gender diverse communities who use additional terminologies

- CERB

- Canada Emergency Response Benefit

- CIS

- Canadian Income Survey

- CRA

- Canada Revenue Agency

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- GBA+

- Gender-based analysis plus

- GST/HST

- Goods and Services Tax/Harmonized Sales Tax

- MBM

- Market Basket Measure

- MBM-N

- Northern Market Basket Measure

List of tables

List of graphs

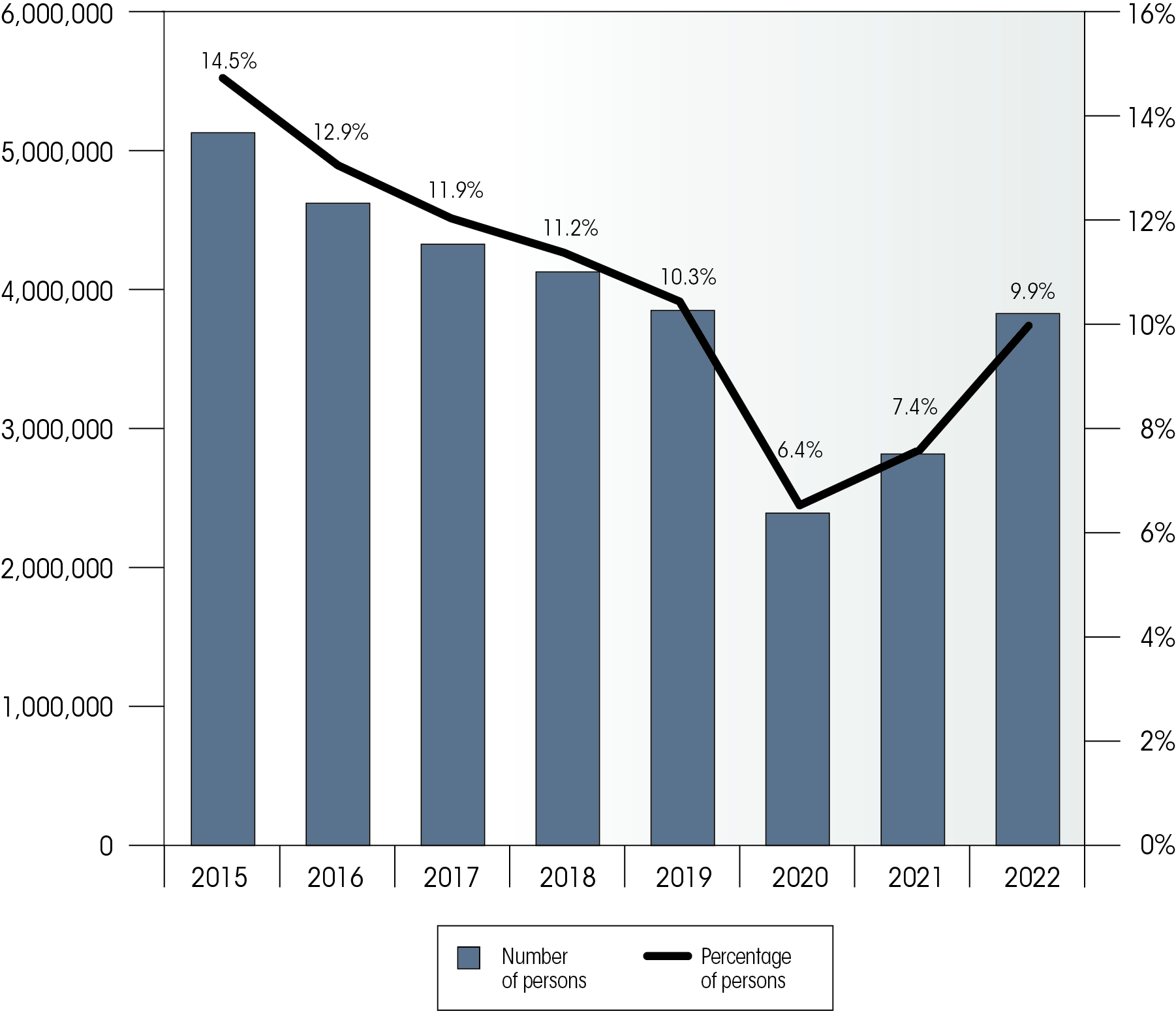

- Graph 1 - Number and percentage of persons living in poverty in Canada based on the Market Basket Measure (MBM) for 2015 to 2022

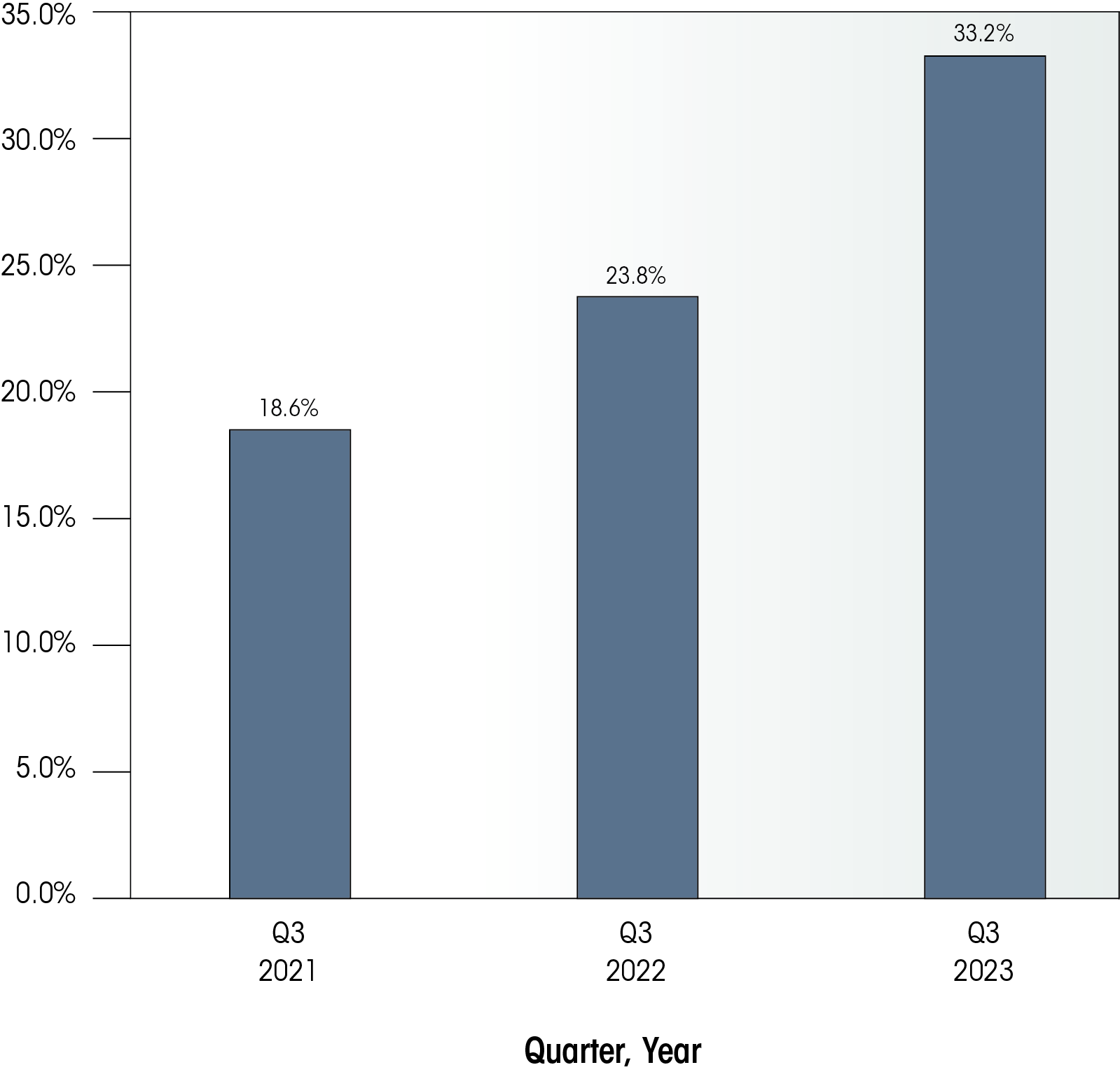

- Graph 2 - Percentage of persons living in Canada aged 15 years and older who found it difficult or very difficult to meet their financial needs in the third quarter of 2021, 2022 and 2023

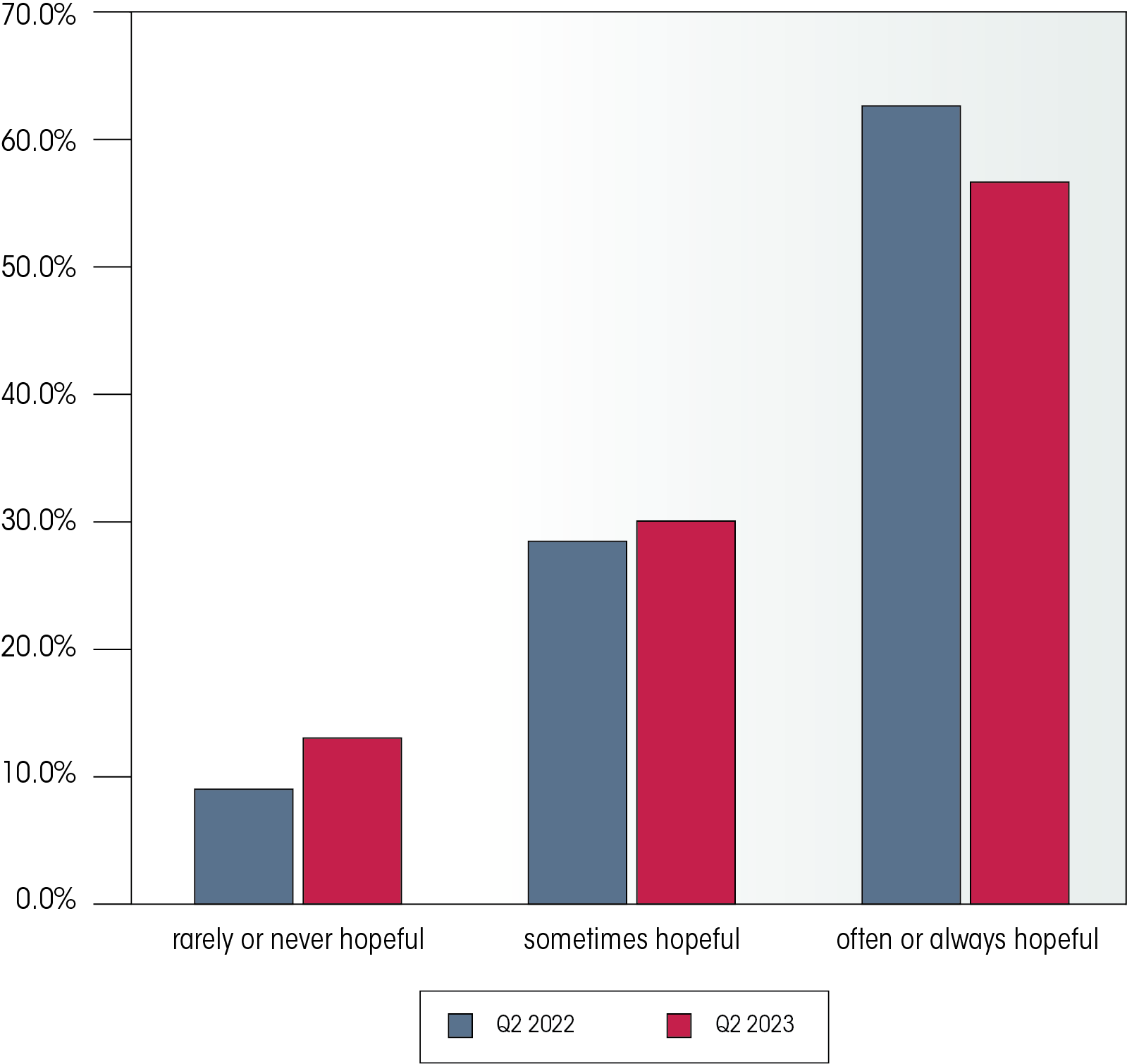

- Graph 3 - Future outlook ratings of persons living in Canada aged 15 years and older in the second quarter of 2022 and 2023

Acknowledgment

The current members of the National Advisory Council on Poverty are proud to present this year's report.

- Scott MacAfee, Chairperson

- Sylvie Veilleux, Member with particular responsibilities for children's issues

- Hannah Brais

- Avril Colenutt

- John Cox

- Kristen Desjarlais-deKlerk

- Nathalie Lachance

- Noah Lubendo

- Kwame McKenzie

- Rachelle Metatawabin

The Council would like to take this opportunity to thank former members of the Council whose work has been foundational in promoting poverty reduction in Canada.

- Alex Abramovich

- Anne Andermann

- Shawn Bayes

- Lisa Brown

- Arlene Hache

- Shane Pelletier

- Cheryl Whiskeyjack

Dedication

The National Advisory Council on Poverty dedicates this 2024 progress report to all the individuals who selflessly shared their stories of success and struggle, with the hope that their expertise will enable better systems and help improve the lives of others living with poverty or at risk of falling into it. You are the thread that binds this report.

We also extend our sincerest gratitude to the lead organizations that provided support to the Council during our visits in Calgary, Halifax and Truro, St. John's, and Whitehorse. The following groups were instrumental in connecting us with individuals with lived experience of poverty and allowing us to gain a better understanding of how poverty is felt in their regions. Thank you to:

- Vibrant Communities Calgary

- Nova Scotia Health-Public Health

- Community Sector Council Newfoundland and Labrador

- Yukon Anti-Poverty Coalition

Message from the Chairperson

I am humbled to present, on behalf of the National Advisory Council on Poverty, our 2024 report on the progress of Opportunity for All - Canada's First Poverty Reduction Strategy.

This year our Council welcomed 6 new members. Their perspectives, care and enthusiasm have helped to evolve the Council and played a big role in the urgent tone and audacious outlook of this report.

In 2024, we ventured out to talk to people in places we've never been, from stark and striking Whitehorse, to downtown Calgary, to the outskirts of Halifax, and to the rocky shores of St. John's. We also spoke to hundreds of organizations during our virtual engagement sessions. The message stayed pretty much the same as in previous years - "we need help, now!" - but was said with much more urgency.

We were particularly distressed by the stories of tragedy and trauma, of lives lost, of deep despair and dread. We heard firsthand of young families torn apart by the very systems that were supposed to support them. We talked with people who were lonely, isolated and desperate. There were people who couldn't see anything getting better and feared what the future holds for all of us.

Overall, this year's conversation about poverty felt heavier than in the past, somehow more urgent. More and more individuals are in survival mode, seeking some sort of stability amid rising costs. The faces were different and the experiences unique, but the challenges raised were unfortunately familiar and similar to those we hear about year after year.

Some themes stood out from the rest. The availability and affordability of safe and suitable housing, the ever-increasing cost of feeding your family, the long hours and low wages of work to barely keep your head above water, service providers becoming clients within their own organizations: these were the things we repeatedly heard.

Having said this, we did see glimmers of hope - hope that if we come together, we can figure out how to do better. We were blown away by the entrepreneurial, innovative and collaborative action we witnessed and heard about.

Thankfully, there are smart, passionate and dedicated people that are focused on doing everything better. They serve so that everyone can be safe and secure in a place they call home, feel cared for and cared about as part of a community, feel empowered, and feel love and belonging. They contribute to creating a Canada where we are all able to match our potential and ambition with the opportunity to build a better life for everyone.

This report outlines the challenges and the conversations we heard. We hope it provides a compelling sense of urgency for continued courageous political action.

Thank you,

Scott MacAfee

Chair, National Advisory Council on Poverty

Executive summary

People living in Canada are facing significant challenges. The poverty rate increased for the second consecutive year in 2022. The 2022 poverty rate was up 2.5 percentage points from 2021 and 3.5 percentage points from 2020. This represents 1.4 million more people living in poverty in Canada in 2022 compared to 2020. If this trend continues, the Government will not only fail to meet its 2030 target of a 50% decrease in poverty compared to 2015, but may also fall back below its 2020 target of a 20% decrease.

A variety of government actions have contributed to a reduction of poverty in Canada since 2015. However, they have not been able to stop the increase in poverty over the last 2 years. Furthermore, the Government's approach to delivering benefits and services has proven insufficient to reaching all those made most marginal.

Meeting vital needs to thrive

This year, in our conversations with communities and stakeholders, we heard a lot about the high cost of goods and services. We also heard about the need to make sure that everyone has access to what they need for a healthy life. This includes access to the resources, means, choices and power necessary to acquire and maintain a basic standard of living and to facilitate integration and participation in society. Among these needs are tangible items like housing, transportation and food, as well as access to services like health care (including mental health care). It also includes intangible things, like a sense of identity, inclusion and dignity.

We heard of urgent needs to increase both minimum wages and social assistance rates to reduce poverty and increase dignity. People shared that because wages are not scaled to inflation, even people who are working full-time, and some who have multiple jobs, live in poverty. We heard throughout the country that government supports at all levels are inadequate and are often well below Canada's Official Poverty Line. Because of this, many people who rely exclusively on government benefits live in poverty by design.

The data shows that costs remain high for key household expenses, such as groceries and housing (Department of Finance Canada, 2024). Further, prices have yet to stabilize as the costs of some vital needs continue to increase significantly. The cost of food increased by 8.9% on an annual average basis in 2022 (Statistics Canada, 2024a). Similarly, costs rose by 6.9% for shelter, 10.6% for transportation, and 4.1% for health and personal care in the same year.

As costs rise, more people living in Canada are finding it challenging to make ends meet, as evidenced by the rising rate of poverty. We heard that, rather than thriving, an increasing number of people are barely surviving. Many people are now falling into poverty because they can no longer afford the things that they need. We heard about families and individuals accessing services when they had never needed to access them before. This includes once-financially-comfortable families facing poverty for the first time.

Improving access to benefits and delivery of services

A wide range of services, programs and benefits are in place to support people living in Canada. Governments at all levels, non-profit organizations and other front-line service providers establish and offer these services. CanadaHelps (2024) reported that 1 in 5 people living in Canada used charitable services to meet essential needs in 2023. Almost 7 in 10 (69%) said this was the first time they relied on charity. This increase in demand for services and products delivered by the non-profit sector is outpacing its capacity.

We heard through our ongoing dialogues that accessing benefits and services is challenging and complex. People noted that systems are difficult to navigate and disconnected, particularly across jurisdictions, but also within and at all levels. People who would benefit most, as well as staff and volunteers supporting clients, are often not aware of what is available or how to access the services and programs. Additionally, some groups, such as those made most marginal, are more likely to live in poverty and face challenges accessing the benefits and services they are entitled to due to systemic inequity and racism.

On the positive side, we met dedicated individuals doing innovative work, building relationships and offering supports to people with complex needs, often filling gaps in the system. We saw many examples of organizations meeting people where they are and supporting more people than ever. Organizations were taking the time to establish connections, nurture relationships and build trust so individuals feel comfortable accepting help and support. On the negative side, we also heard that non-profit organizations rarely receive sustained long-term funding or funding for basic operational requirements. This makes it difficult to provide holistic support to address complex needs while maintaining daily operations. Organizations described how stable funding allows them to undertake longer-term projects and innovate. Inadequate and limited funding, combined with outdated support systems, make it challenging for organizations to keep up with the rising demand. This has contributed to burnout in the sector.

Building strong communities and enabling equity

The Council has been met with a sense of desperation during our dialogue with individuals and stakeholders across Canada this year. The challenges faced by people during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent economic situation may have created discord and fear about what will come next.

We heard from a lot of people who are operating in what they describe as "survival mode." They explained that because they have unmet vital needs compounded by dealing with trauma, substance use, homelessness or any of the other challenges closely associated with poverty, surviving is often their only thought. These conditions - experiencing poverty and being in survival mode - are actively traumatizing.

We heard that many people are more likely to be thinking specifically about their own families and communities, and that the bridges between people and between communities are starting to give way. This could have serious consequences for individuals and for society. It could lead to increased loneliness, isolation and mental health problems. It could also lead to divisiveness and discrimination. Left unchallenged, it could undermine society and our ability to help those made most marginal.

Communities are struggling with increasing resource disparity and limited access to health care, services and opportunities. Those new to poverty may be in shock and concerned with surviving while navigating complicated and unfamiliar systems. We heard that those who are not new to living with poverty have seen a deterioration in the supports that they receive.

With the lack of affordable housing, more people access shelters, live in encampments or sleep rough on the street. We heard that often people do not feel safe in shelters, and there are insufficient alternate options. Tent encampments have become widespread and are no longer just in urban areas where they may have been historically. Homelessness is more visible as a result.

And, for some, these issues are superimposed on existing problems that need specific solutions. We heard from Indigenous people, Black people and people from other racialized groups about the myriad of ways colonization impacts them. Not only has colonization taken place in Canada, but Canada has supported colonial systems internationally. People living in Canada may have been impacted by colonialism internationally before coming to Canada. Both have ramifications on the development of trust between communities and government. Neocolonial practices impact those made marginal and undermine trust and connections between people by:

- using colonial structures as the basis for dialogue and service delivery

- using Eurocentric approaches

- ignoring the systemic nature of racism and discrimination

Racialized persons were more likely to live below the poverty line in 2022 (13.0%) than non-racialized persons (8.7%). Among racialized groups, the poverty rate was highest for persons identifying as Arab (18.7%), Chinese (15.6%) and Black (13.9%). We heard that a concerted effort to focus on decolonization is required.

Recommendations

Governments at all levels, communities, and private sector actors have made significant investments that could decrease poverty. The Council recognizes the Government of Canada's role in developing and reinforcing a suite of programs and supports to strengthen Canada's social safety net. These investments have reduced the overall poverty rate in Canada significantly relative to 2015. However, while the poverty rate is lower than it was in 2015, Canada's poverty rate increased in both 2021 and 2022 after decreasing for several years.

The convergence of multiple crises, leading to an increase in poverty, leaves people with a sense that things are not getting better anytime soon. People feel desperate, hopeless and overwhelmed at the variety and constant nature of the challenges they face. Many stakeholders expressed frustration about the lack of coordinated efforts and the need to update antiquated government systems that force people to rely on charity to meet their vital needs. They don't see a way out. This is especially true for those who have experienced poverty for generations. There is a sense of urgency and a need for immediate transformative action throughout the country.

Government needs political courage to create change. Specifically, the federal government has to play a convening role in bringing people together. The Government needs to confront the forces perpetuating the inequity of poverty and ensure that everyone has an adequate income whether through employment or government benefits.

Meeting vital needs to thrive

Recommendation 1

The Council has seen the devastating impact of living with poverty, particularly during our discussions with people experiencing poverty. We recommend that the Government's current target of a 50% reduction in poverty (set in the Poverty Reduction Act) be seen as a staging post toward a more ambitious goal of a Canada with no poverty. Given the impacts of poverty that this Council has witnessed, we recommend that the Government work toward zero poverty. An important consideration for achieving zero poverty is the adequacy of government benefits. Relying on government benefits, in the short or long term, should not mean living with poverty.

The Council proposes that the federal government should:

- work across governments to introduce a basic income floor, indexed to the cost of living, that would provide adequate resources (above Canada's Official Poverty Line) for people to be able to meet their basic needs, thrive and make choices with dignity

- while working toward a basic income floor, increase income security by incrementally reforming current benefits to increase benefit amounts. A twin approach of ensuring adequate funding of state welfare programs and decreasing inequities by targeting increases to the groups made most marginal could help achieve this goal. Specific improvements to programs could include:

- introducing legislation to leverage Canada Social Transfer payments to provinces and territories to ensure that social assistance rates in each jurisdiction meet a percentage of the Market Basket Measure

- taking a human-centred approach to benefits that can provide flexibility to support unique scenarios and important life transitions

- providing a plan to build up the Canada Disability Benefit in both accessibility and adequacy and ensure it functions as a stackable benefit with provincial/territorial programs and does not result in any clawbacks

- separating maternity and parental benefits from the Employment Insurance program so that they are not tied to employment, and increasing the amount that the benefit provides so that people are not living with poverty in the first year of their child's life

Recommendation 2

To address the housing challenges facing people living in Canada, the federal government should:

- work with the provinces, territories and municipalities to develop a plan with targets to decrease core housing need for people who are spending 30% to 50% of their income on housing. This includes an expansion of non-market-linked housing (housing managed by government or non-profit organizations) that corresponds to the needs of different communities and different family sizes and types. Prioritizing non-market housing would support the development of affordable not-for-profit housing, rather than investment properties

- introduce and oversee the implementation, delivery and coordination of federal rental subsidies that:

- include a percent to account for energy and utility costs

- are associated with the individual, not the property (following tenants between rentals), allowing people to choose their own housing (unlike subsidized housing where people typically have no choice over where they live)

Recommendation 3

To increase food security, the federal government should:

- in support of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 2 (end hunger, achieve food security, improve nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture), establish government regulation of nutritious food prices. This could be done for items included in the National Nutritious Food Basket used in the development of the Market Basket Measure

- when implementing the National School Food Program, ensure that it is low-barrier, stigma-free, equitable and inclusive, and provides nutritious food. Additionally, consideration should be given to promote programs that offer both breakfast and lunch, that offer culturally appropriate options and that involve local producers

Improving access to benefits and delivery of services

Recommendation 4

To facilitate low-barrier and equitable access to benefits and services, the Government should:

- explore ways to expand auto-filing and auto-enrollment for people living with poverty to ensure that all available benefits and supports are accessed by all those eligible at the federal, provincial and territorial levels

- fund systems navigation initiatives to help people through the benefits and services system

Recommendation 5

To support the non-profit sector that provides a vital and essential role in supporting those who have been made most marginal, the federal government should use its leverage to:

- provide stable, long-term, operational funding for non-profit organizations that allows for flexibility and autonomy in how organizations are managed

- mandate funding that supports and ensures fair and equitable wages and working conditions for employees in the non-profit sector

- reduce the administrative burden associated with the funding process (application, implementation and reporting) but ensure that accountability is in place to measure the impact of the investments

- support organizations that promote innovation in response to their clients' and target audiences' needs

Building strong communities and enabling equity

Recommendation 6

To increase equity and to work to build strong communities, the Government of Canada should:

- take urgent action to respect treaty rights and support Indigenous leaders to reduce poverty in their communities and to ensure that they have all the resources available to support their own people in their own way. This includes urgently implementing the Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Calls for Justice from Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls

- develop a plan to address poverty inequality - specifically, a plan to decrease the poverty rate in marginalized groups to meet or be lower than the average poverty rate in Canada

- such a plan should:

- promote and increase equity in program and policy design and implementation

- reduce stigma around poverty, including helping everyone see individuals as humans, equals and essential, regardless of income or social condition

- explain how current poverty reduction measures would be tailored to specifically meet the needs of the populations made most marginal

- set clear targets of equity to be met by 2030, at the latest

- include accountability and evaluation mechanisms to monitor implementation of the plan

- potential plan activities could include:

- developing mandatory training for all federal front-line government service providers, including trauma-informed service delivery and equity and anti-racism training

- eliminating racism and discrimination from child welfare decisions. Solutions to poverty are needed rather than using child welfare as a circuitous solution to poverty (removing children experiencing poverty from their family, which has side effects such as cultural, linguistic, familial and emotional upheavals)

- ensuring that newcomers have adequate and equitable access to benefits

- introducing new measures to address poverty among children and youth, including families who are caring for children with disabilities

- such a plan should:

Chapter 1: Setting the scene

Canada's first Poverty Reduction Strategy and the creation of the National Advisory Council on Poverty

In 2018, the Government of Canada released Opportunity for All - Canada’s First Poverty Reduction Strategy. The Poverty Reduction Strategy set a vision and foundation for future government investments in poverty reduction. This foundation included:

- establishing an official measure of poverty, Canada's Official Poverty Line, based on the Market Basket Measure

- setting concrete poverty reduction targets to reduce poverty by 20% by 2020 and 50% by 2030, relative to 2015 levels. In 2015, the poverty rate was 14.5%, representing over 5 million people living in Canada who were in poverty

- creating a National Advisory Council on Poverty (established in 2019) to:

- advise the Government on poverty reduction

- report publicly on the progress made to meeting the targets every year

- foster a national dialogue on poverty reduction

- passing the Poverty Reduction Act, which entrenches the targets, Canada's Official Poverty Line, and the Council in law

Progress on meeting Canada's poverty reduction targets

Poverty reduction targets

Every year, we report on the progress made toward meeting the targets to reduce poverty by 20% by 2020 and 50% by 2030, relative to 2015 levels.

How poverty is measured

A person's or family's income level and their experience of poverty are different. However, income is often used as a proxy to measure poverty. The Poverty Reduction Act (2019) established an Official Poverty Line for Canada based on the Market Basket Measure (MBM).

Market Basket Measure

The MBM establishes poverty thresholds based on the cost of a specific basket of goods and services representing a modest, basic standard of living. It includes the costs of food, clothing and footwear, shelter, transportation and other items for a reference family. The current MBM methodology sets poverty thresholds for 53 geographic regions in the provinces and 13 regions in the territories. Such thresholds are adjustable to reflect families of different sizes. An individual or family having a disposable income below the threshold, for the size of their family in a particular region, is considered to be living in poverty.

The current MBM uses a 2018 base. In June 2023, Statistics Canada launched the third comprehensive review of the MBM. The review will be completed in 2025 and will result in a new 2023 base that will ensure the continued accuracy of the measure (Devin et al., 2023).

The Northern Market Basket Measure (MBM-N) for Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut uses a similar methodology to the MBM for the provinces. However, it includes adjustments needed to reflect life in these territories.

MBM statistics are not produced for certain populations that are under-surveyed or not surveyed at all. For example, MBM statistics are not produced for First Nations people living on-reserve, people living in institutions, 2SLGBTQI+ people, people with refugee status, people seeking asylum, and people experiencing homelessness.

Canadian Income Survey

Data from the Canadian Income Survey (CIS) are used to estimate poverty rates based on Canada's Official Poverty Line. The CIS is an annual survey with an approximate 16-month lag between the end of the reference year and the availability of the results. The most current statistics are from the 2022 CIS, released on April 26, 2024.

Poverty in Canada, 2022

In 2022, according to Canada's Official Poverty Line, the poverty rate was 9.9%, and about 3.8 million people living in Canada were in poverty (Statistics Canada, 2024f). This represents a 32% reduction in the poverty rate compared to 2015 (14.5%) and roughly 1.3 million fewer people living in poverty in Canada. The Government of Canada has met its first poverty reduction target (20% by 2020 relative to 2015).

While poverty has decreased since 2015, the poverty rate increased for a second consecutive year in 2022. The 2022 poverty rate was up 2.5 percentage points from 2021 and 3.5 percentage points from 2020. This represents 1.4 million more people living in poverty in Canada in 2022 compared to 2020. If this trend continues, the Government will not only fail to meet its 2030 target of a 50% decrease in poverty compared to 2015, but may also fall back below its 2020 target of a 20% decrease.

High rates of poverty among groups made most marginal reflect persistent inequality throughout the country. In particular, racialized persons were more likely to live below the poverty line in 2022 (13.0%) than non-racialized persons (8.7%). We provide further information on poverty among groups made most marginal in chapter 4.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Income Survey, Table 11-10-0135-01 Low income statistics by age, sex and economic family type.

- Note: The percentage and number of persons living in poverty in Canada exclude the territories.

Text description of Graph 1

| Year | Number of persons in poverty | Percentage of persons in poverty |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 5,044,000 | 14.5% |

| 2016 | 4,552,000 | 12.9% |

| 2017 | 4,260,000 | 11.9% |

| 2018 | 4,065,000 | 11.2% |

| 2019 | 3,793,000 | 10.3% |

| 2020 | 2,357,000 | 6.4% |

| 2021 | 2,762,000 | 7.4% |

| 2022 | 3,772,000 | 9.9% |

Poverty in the provinces

The poverty rate varies by province. It has gone up in every province between 2021 and 2022. Having said this, it remains below the 2015 level in every province except Alberta.

| Province | 2015 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 13.0% | 8.1% | 9.8% |

| Prince Edward Island | 15.7% | 7.4% | 9.8% |

| Nova Scotia | 16.8% | 8.6% | 13.1% |

| New Brunswick | 16.2% | 6.7% | 10.9% |

| Quebec | 13.5% | 5.2% | 6.6% |

| Ontario | 15.1% | 7.7% | 10.9% |

| Manitoba | 14.1% | 8.8% | 11.5% |

| Saskatchewan | 12.2% | 9.1% | 11.1% |

| Alberta | 9.4% | 7.8% | 9.7% |

| British Columbia | 18.6% | 8.8% | 11.6% |

Poverty in the territories

Canada's overall poverty rate (based on the MBM) excludes the poverty rates (based on the MBM-N) in the territories. According to the MBM-N, the poverty rate in the territories for 2022 was 24.2%, an increase from 20.2% in 2021 (Statistics Canada, 2024l).

In Yukon, the 2022 poverty rate was 12.9% (about 5,200 people), up from 7.7% in 2021. In the Northwest Territories, the poverty rate increased from 15% in 2021 to 17.1% (about 7,300 people) in 2022. In Nunavut, the 2022 poverty rate was 44.5% (about 16,700 people), compared to 39.7% in 2021.

Of note, the official poverty rates for Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut are higher than Canada's overall poverty rate. High poverty rates in the territories are consistent with what we have heard about higher costs of living in the territories and continued racism that makes it more likely for Indigenous people to live in poverty.

Indicators of poverty

Income alone fails to capture the full experience of living with poverty. Opportunity for All - Canada's First Poverty Reduction Strategy (Employment and Social Development Canada, 2018) established a dashboard of 12 indicators related to poverty. The dashboard is not comprehensive, but it allows progress to be tracked across several dimensions of poverty. The descriptions and latest statistics for each indicator are available on the Dimensions of Poverty Hub (Statistics Canada, 2024g). Statistics Canada publishes and maintains the Hub and tracks these indicators. The Government of Canada is also working to co-develop distinctions-based Indigenous indicators of poverty and well-being.

Several of the indicators have worsened since 2015 (or their initial year of measurement since tracking began under the Poverty Reduction Strategy). These trends are concerning and are present for the following indicators:

- food insecurity (16.9% of respondents reported being in moderate or severe food insecurity in 2022, compared to 11.6% in 2018, when this data was first collected)

- unmet health care needs (9.2% of people reported unmet health care needs in 2022 compared to 5.1% in 2018, when this data was first collected)

- literacy and numeracy (low literacy rates increased from 10.7% in 2015 to 18.1% in 2022; low numeracy rates increased from 14.4% in 2015 to 21.6% in 2022)

- average poverty gap ratio (increased to 32.4% in 2022 from 31.8% in 2015)

- low income entry rates (increased from 3.9% in 2015-2016 to 5.5% in 2020-2021)

As well, several indicators have followed a trend similar to that of the poverty rate. Despite some improvements, in recent years, the following indicators have moved closer to their baseline in 2015 (or their initial year of measurement since tracking began under the Poverty Reduction Strategy):

- deep income poverty (decreased from 7.4% in 2015 to 5.0% in 2022)

- relative low income (decreased from 14.3% in 2015 to 11.9% in 2022)

- bottom 40% income share (increased from 20.2% in 2015 to 21.1% in 2022)

- low income exit rate (increased from 27.6% in 2015-2016 to 29.1% in 2020-2021)

Taking stock of progress in poverty reduction

Poverty reduction is complex and requires a whole-of-society approach that includes provincial, territorial and municipal governments, employers, non-profit and community organizations, and individuals. Federal government investments and programs interact with provincial and territorial benefits and programs that, in turn, interact with local programs and services. However, the federal government is responsible for the targets set out in Opportunity for All and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Since 2015, the federal government has introduced a series of measures and made a range of commitments seeking to reduce poverty, including:

- the Canada Child Benefit

- a top-up to the Guaranteed Income Supplement

- investments in early learning and child care

- expanding the Canada Workers Benefit

- investments in housing

- the creation of new job and training opportunities for workers

- establishing a $15 federal minimum wage benefiting workers in the federally regulated private sector

- introducing the Canadian Dental Care Plan and the National Pharmacare Plan

- launching a National School Food Program

- introducing the Canada Disability Benefit

These investments have contributed to (or intend to contribute to) the reduced poverty rate in Canada. Additionally, the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) provided during the COVID-19 pandemic further contributed to significant reductions in the overall poverty rate during 2020. However, the poverty rate has recently been on the rise, increasing in both 2021 and 2022.

Some challenges in the Government's approach to poverty reduction persist. Investments can help to improve the financial security of people living in Canada either by providing additional income directly to families and individuals or by reducing the costs of necessary goods and services. However, investments are not enough to fully lift people out of poverty, as evidenced by the recent increase in the poverty rate. Furthermore, the Government's approach to delivering benefits and services is not necessarily reaching all those made most marginal. Those made most marginal are more likely to live in poverty and tend to be populations that are hardest to reach (Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2022a). Without addressing these systemic challenges, poverty reduction measures may be less effective than needed to meet the federal government targets.

Ongoing dialogue

To inform its work and the content of this report, in 2024, the Council combined in-person meetings in 4 regions across Canada with 5 virtual sessions. The Council visited and met with individuals and groups in Calgary (Alberta), Halifax and Truro (Nova Scotia), St. John's (Newfoundland and Labrador) and Whitehorse (Yukon). The virtual thematic sessions focused on:

- the complexity and different layers of poverty

- housing, food security and cost of living

- efforts to empower those made most marginal

- rising poverty in Canada

Annex A provides a list of organizations that participated in these sessions.

This year's activities complemented those undertaken by the Council since its inception, which include 47 virtual engagement sessions in the past 4 years and in-person visits in:

- Alberta (Edmonton)

- British Columbia (Abbotsford, New Westminster, Surrey and Vancouver)

- Manitoba (Winnipeg)

- Northwest Territories (Yellowknife)

- Ontario (Ottawa and Toronto)

- Quebec (Montréal, Huntington and Salaberry-de-Valleyfield)

- Saskatchewan (Prince Albert, Regina and Saskatoon)

We take this approach to reach as many people as we can. It is important for us to meet people with lived experience, in person and where they are. Through our reports, we want to speak to the experiences they choose to share. It has, again this year, been a privilege to speak to people with lived experience of poverty, stakeholders, service providers, staff in the non-profit sector, and experts in their fields. The ideas shared in the "what was heard" sections of this report reflect those of individuals and organizations touched by poverty, directly or indirectly, day to day.

Throughout this year's dialogue, the dominant themes we heard included:

- how much people are struggling with the high cost of living

- the shift in social connections

- the challenges faced by service providers to keep up with the demands of increasing poverty

This report presents a summary of the information gathered through this Council's ongoing dialogue with people living in Canada. It also presents an analysis of the key themes emerging from these conversations and recommendations for federal consideration to help address poverty throughout the country.

Chapter 2: Meeting vital needs to thrive

Policy context

Overview and data

People living in Canada are facing significant financial challenges. This is in large part because costs remain high for key household expenses, such as groceries and housing (Department of Finance Canada, 2024). Further, prices have yet to stabilize as the costs of some vital needs continue to increase significantly. The cost of food increased by 8.9% on an annual average basis in 2022 (Statistics Canada, 2024a). Similarly, costs rose by 6.9% for shelter, 10.6% for transportation, and 4.1% for health and personal care in the same year.

As costs rise, more people living in Canada are finding it challenging to make ends meet. We heard that, rather than thriving, people are barely surviving. According to the Canadian Social Survey, the proportion of people living in Canada aged 15 years and older who found it difficult or very difficult for the household to pay for their financial needs increased between the third quarters of 2021 (18.6%) and 2022 (23.8%) (Statistics Canada, 2024d). By 2023, this jumped to 33.2% (Graph 2).

- Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Social Survey, Table 45-10-0087-01 Difficulty meeting financial needs, by gender and other selected sociodemographic characteristics.

Text description of Graph 2

| Quarter, Year | Percentage of persons who found it difficult or very difficult to meet their financial needs |

|---|---|

| Q3, 2021 | 18.6% |

| Q3, 2022 | 23.8% |

| Q3, 2023 | 33.2% |

The cost of living is rising faster than wages putting pressure on government benefits that alone aren’t sufficient to lift people out of poverty. This has contributed to an increase in the poverty rate for the second year in a row (from 6.4% in 2020 to 9.9% in 2022). Consumer prices rose faster than average hourly wages on a year-over-year basis from October 2021 to April 2022, meaning Canadians experienced a decline in purchasing power. The latest data show that from July 2021 to July 2022, consumer prices increased by 7.6%, while average hourly wages rose 5.2% (Statistics Canada, 2022b).

The percentage of people in Canada living in deep income poverty (disposable income that is below 75% of Canada's Official Poverty Line) has also increased for the second consecutive year, from 3.0% in 2020 to 5.0% in 2022 (Statistics Canada, 2024g).

Housing, food and transportation all represent considerable costs that are continually growing. As a result, some people can no longer afford them and are going without one or all. These goods and services help meet vital needs. People who are deprived of them, especially children, can suffer serious repercussions to their physical and mental health and well-being. It can also impact their ability to participate in society and lead to social exclusion.

Wages and benefits, along with supports to meet people's needs, haven't been adequate during this difficult economic period. The rising poverty rate is proof of this lack of support. The current economic challenges are not just impacting people with lived or living experience of poverty, though they are more likely to face challenges. Many people living above the poverty line are also having difficulty affording the higher cost of goods, particularly if their incomes have stayed the same.

In 2023, cost-of-living increases – especially for housing and transportation – outpaced income gains for lower income households (Statistics Canada, 2024e). This has not only impacted the ability of people to pay for their immediate needs but has also impeded their ability to save for the future. For example, in contrast with a 12.6% gain in net saving for households in the highest income quintile, net saving for the lowest-quintile households decreased by 7% in 2023 relative to a year earlier (Statistics Canada, 2024e).

The current situation is leading to different types of poverty or resource deprivation. The high cost of vital needs is leaving little or no money for discretionary spending. The 2021 Census showed that about 5.6% of households in Canada were energy poor (spending 10% or more of household after-tax income on energy bills) (Dionne-Laforest et al., 2024). Energy poverty rates were higher in the Atlantic provinces, ranging from 10.7% to 13.7%.

Among 67 communities in Canada that participated in nationally coordinated point-in-timeFootnote 1 homeless counts both in 2018 and in 2020-2022, the number of persons experiencing homelessness increased by 20% (Infrastructure Canada, 2024a). Further, Infrastructure Canada reported a 23.4% increase in emergency shelter use in 2022 compared to 2021 (Infrastructure Canada, 2024b).

Meeting the vital needs of children and youth is particularly important because the impacts of experiencing poverty as a child can continue throughout a person's life. Early interventions for families can help to meet the needs of children and youth before they fall into poverty.

The federal government is making ongoing investments to help people cope with these costs. However, government transfers to individuals and families decreased for the second year in a row in 2022. During that year, the Government discontinued all pandemic-related benefits and removed modifications to the Employment Insurance program (Statistics Canada, 2024f). These changes contributed to median government transfers decreasing to $14,200 in 2021 and $10,100 in 2022 after having reached an all-time high of $18,100 in 2020 (adjusted for inflation). This decrease, combined with relatively no change in market income, meant that the median after-tax income of families and unattached individuals decreased from $73,000 in 2021 to $70,500 in 2022 (Statistics Canada, 2024f).

In 2022, about 6.4 million people living in Canada (16.9%) lived in households that experienced moderate or severe food insecurity (Statistics Canada, 2024h). This is up from 4.8 million (12.9%) in 2021. Among those at the highest risk were persons in female-led lone-parent families (36.5%), the Black population (31.9%), Indigenous persons living off-reserve (28.6%), and unattached non-seniors (25%). The rate of food insecurity was also high among children (aged 17 years and younger), at 21.0%. The rates of moderate and severe food insecurity for other groups are presented in Table 2.

| Demographic group | Rate of moderate or severe food insecurity |

|---|---|

| OverallƗ | 16.9% |

| Children (aged 17 years and younger) | 21.0% |

| Seniors (aged 65+) | 8.0% |

| Unattached non-seniors (under age 65) | 25.0% |

| Persons in lone parent families | 34.0% |

| Persons in male-led lone parent families | 23.2% |

| Persons in female-led lone parent families | 36.5% |

| ImmigrantsƗƗ (aged 15+) | 17.2% |

| Recent immigrantsƗƗ (10 years or less) aged 15+ | 21.2% |

| Very recent immigrantsƗƗ (5 years or less) aged 15+ | 19.3% |

| Indigenous people living off-reserve (aged 15+) | 28.6% |

| Racialized personsƗƗƗ | 20.7% |

| Chinese | 13.4% |

| Black | 31.9% |

| Latin American | 23.5% |

| Filipino | 20.6% |

| Arab | 18.3% |

| South Asian | 17.6% |

| Southeast Asian | 16.6%* |

| Other racializedƗƗƗ persons** | 26.8% |

| Not a racialized personƗƗƗ nor Indigenous | 14.7% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Income Survey, Table 13-10-0835-01 Food insecurity by selected demographic characteristics; Table 13-10-0834-01 Food insecurity by economic family type.

- Notes:

- Ɨ The estimated food insecurity rates in this table only include data from Canada's provinces.

- ƗƗReferred to by Statistics Canada as people who are, or have been, landed immigrants in Canada. Canadian citizens by birth and non-permanent residents (persons from another country who live in Canada and have a work or study permit, or are claiming refugee status, as well as family members living here with them) are not considered landed immigrants.

- ƗƗƗReferred to by Statistics Canada as persons designated as visible minorities.

- *Statistics Canada indicates that these data should be used with caution.

- **Other racialized persons includes racialized groups other than Black, Chinese, Latin American, Filipino, Arab, South Asian or Southeast Asian, as well as persons who identified as more than one racialized group.

Although a more detailed breakdown is not available for the territories, 36.4% of people in the territories lived in a household that experienced some form of food insecurity (marginal, moderate or severe) (Statistics Canada, 2024l).

As poverty and material deprivation are increasing, more people are accessing services, like food banks, or increasing debt to make ends meet. In HungerCount 2023, Food Banks Canada reported that food bank usage increased by 32% between March 2022 and March 2023 (Food Banks Canada, 2023). In spring 2022, Statistics Canada conducted a Portrait of Canadian Society survey. Of respondents, 27% reported having to borrow money from friends or relatives, take on additional debt or use credit to meet day-to-day expenses in the 6 months before the survey (Statistics Canada, 2022a).

What we heard in the ongoing dialogues

The remainder of this chapter reflects what the Council heard from individuals who shared their expertise, experiences and opinions. The thoughts expressed do not necessarily reflect our opinions as a Council or the available data or research.

Key themes

The rising cost of living is pushing more people toward poverty

"Poverty can happen to anybody."

Many people are now falling into poverty because of the high cost of the goods and services that they need. We heard about more families and individuals accessing services, many for the first time. This includes once-financially-comfortable families facing poverty for the first time. More of the population is increasingly experiencing over-indebtedness, as people take on more debt to afford necessities and pay bills. People who have never experienced poverty but now live in shelters or encampments expressed shock about how they ended up in this position.

"You should not have to choose between putting a roof over your and your child's head or feeding your child."

Many people are working multiple jobs to stay afloat, and others are reducing costs by:

- delaying moving into their own dwelling

- moving into crowded and inadequate housing

- cutting out leisure activities

- reducing their food intake

- changing their diet by buying unhealthier, low-cost food items

- choosing between heat and other necessities like groceries

"I had it all until I didn't."

We heard that some people who are new to poverty are often hesitant to reach out for help for many reasons:

- they may not access food banks or shelter services due to a perceived stigma

- services are not always dignified or offered in a safe, trauma-informed space

- there is a social expectation or tendency to encourage people to exhaust all other options before reaching out

- they fear they may face consequences for reaching out, such as intervention and apprehension of children by social services

- many people who are new to poverty may not know what services are available because they never believed they would need to access them

"I wasn't aware of the women's shelter and food programs because I didn't think I needed them."

This can lead to isolation and desperation among people who need help and who have not been connected to services before.

Wages and benefits are not keeping pace with the cost of living

"During COVID, they deemed that everyone needs $2,000 a month to live, and that was 2020. Now it's 2024, and we don't get that."

We heard of urgent needs to increase both minimum wages and social assistance rates to reduce poverty and increase dignity. People shared that because wages are not scaled to inflation, even people who are working full-time, and some who have multiple jobs, live in poverty. People spoke about a mismatch between the living wage and the actual wages. In many regions, this may be caused by the high cost of living and the presence of sectors with predominantly lower-paid work. Many participants felt that employers have responsibilities to pay their employees fair, living wages.

"You're telling me to make something of my life, but you are making it hard for me to do so."

We heard throughout the country that government supports at all levels are inadequate and are often well below Canada's Official Poverty Line. Because of this, many people who rely exclusively on government benefits live in poverty by design. They shared that they often have nothing left for food or for anything else after paying rent and utilities. Social assistance falls well below the poverty line in every jurisdiction, and clawbacks for employment income can reduce incentives to work.

Among people with disabilities, the poverty rate is high due to the difference between the benefits and the actual costs of living with a disability. For new parents, Employment Insurance benefits during maternity and parental leave result in significant drops in income at a time when costs are high. While social assistance is a provincial and territorial responsibility, we heard from many people that the federal government should take on a convener role to ensure that benefits work together to raise people above Canada's Official Poverty Line.

Meeting vital needs to thrive

This year we heard a lot about the cost of goods and services and the need to make sure that everyone has access to what they need for a healthy life. This includes access to the resources, means, choices and power necessary to acquire and maintain a basic level of living standards and to facilitate integration and participation in society. Among these needs are tangible items like housing, transportation and food, as well as access to services like health care (including mental health care). It also includes intangible things, like a sense of identity, inclusion and dignity.

Housing

"Housing is a massive crisis right now."

The rising costs and challenges in accessing safe, high-quality, affordable housing is a top concern for people with lived experience in poverty, service providers, advocates, and non-profit organizations. In every session, stakeholders raised housing insecurity as one of the biggest challenges facing people across the country, regardless of their income.

High-quality, stable housing is necessary. Without stable housing, individuals we met with indicated it would be impossible to feel safe and secure and to exit from poverty. Housing stability is the extent to which an individual's customary access to housing of reasonable quality is secure. Housing is necessary for health, mental health, well-being, success in education, and obtaining employment. Stable, supportive housing also plays an important role in recovering from trauma and substance use, facilitating social inclusion and enhancing one's well-being.

It is becoming harder to access housing across the income spectrum. The cost of housing is rising rapidly, and the lack of safe, affordable housing limits people's capacities to find anywhere to live, let alone somewhere safe. Cities and neighbourhoods that used to be affordable are no longer so. The lack of affordable housing is contributing to bottlenecks throughout the system. Namely, we heard that rising interest rates and housing costs are pushing people who wish to own a home out of home ownership and into the rental market. In turn, this increases the rental market demand and reduces access to affordable rental units. This pushes people into unstable housing, homelessness and shelters. The lack of affordable housing prevents people from moving from shelters into housing.

"We are at capacity at our shelters because we can't move people on. There is no safe, affordable housing to move people into."

Transitional and supportive housing for those leaving homelessness and the shelter system, particularly those with complex needs, is limited or lacking. This makes it more likely for people to stay in shelters longer or return to the shelter system after leaving. Shelters can't keep up with the rising demand. Even expanded shelters are still full. Across jurisdictions, people shared stories of shelters that have had to turn people away due to lack of space.

We also heard about a need for secondary housing options for people ready to leave transitional housing, but not yet ready to live independently. These second-stage housing units would provide less support and more independence and could house people for a longer time than typical transitional housing. The intent is a system of supportive housing that helps more people successfully transition out of the system. The people who have experienced chronic homelessness need the most support.

More people are turning to tent encampments, and there is more diversity in terms of the people who are homeless and living in them (for example, seniors and single women). When encampments are closed, and people are displaced, they don't just lose the place where they were living. Displacement also means, in many cases, the loss of their possessions, their sense of community, the networks they have established, the services they access, and so much more.

"Housing is a human right, but it's not treated as such because it's so focused on making money."

We heard about the impact of the financialization of housing. Some people are benefiting financially from high interest rates and housing costs. This leaves those made most marginal particularly at risk of being pushed out of the housing market (both ownership and rental).

Personal stories of challenges accessing housing

A single mom with a baby shared that she has been searching for adequate housing for more than 14 months. She is currently living in a studio apartment in a hotel that was converted to social housing. She has only a hot plate and a bar-sized refrigerator, not big enough to hold the formula for her child and food for more than a day. She is on a waiting list for a better housing unit; however, she must wait, because the criteria are not flexible:

- her revenue in the previous year was more than $38,000, but she had to leave a bad situation and is now a student and single mom

- she has to wait for a 2-bedroom because the system defines her as a 2-person household (her and her child), but she would be more than willing to take a 1-bedroom unit

- she is also told that because she has a place (even if inadequate), her case is a low priority

Another young mother housed by community services in a hotel became homeless after giving birth to her child prematurely. Due to medical complications, she had to stay in the hospital longer than expected. Because of this, community services cancelled her accommodations. The hospital discharged her without a place to go, so she had to go to a shelter. Social services wouldn't let her leave with a baby to "go live on the streets" and apprehended the baby to put into foster care. So, the system is paying for foster care instead of paying for a safe place for the mother and child to live together.

"Who is benefiting from the high rents?"

Besides the financial impact, high rents can have other implications:

- some people are forced to stay in unsafe or unhealthy housing because they can't afford to leave

- many people don't feel able to assert their rights as renters for repairs in their accommodations for fear of being kicked out and becoming homeless

- some people are renting less expensive housing by paying cash under the table. This housing is often inadequate and unsafe, and the landlords have total control with no legal recourse for the renters

- with low vacancy rates, landlords can charge whatever they want, and feel emboldened to take advantage of tenants

- vulnerable youth, women and seniors remain in harmful situations like intimate partner violence, abuse and neglect because they know they will not be able to afford housing

"Women are staying [in abusive relationships] because the cost of housing is not manageable for a single individual. Most times, it's not even manageable for 2 people."

We heard that much of the Government's support for housing is to support the industry to build houses, but these units are not affordable, and they are definitely not deeply affordable. There is no incentive to build different types of housing such as co-operative and community-owned housing or dwellings that work for different family makeups beyond a typical nuclear family (for example, large families, intergenerational families, roommates). There needs to be production of deeply affordable, mixed-style housing outside the market where the aim is to provide housing rather than make a profit.

"The federal government investments in housing are not actually positioned to reduce core housing need and reduce homelessness. They are to support the private markets builders and with very little regulation on what is done."

Food security

"When I go into the supermarket and look at food, like a lot of seniors, I just have to walk away because I can't afford it."

Stakeholders told us that rising food prices are hitting people hard. This is especially true for those with the lowest incomes. Because fixed costs, particularly housing and energy, are so high, the budget left for food can be little or nothing. Sometimes, high food prices mean people have had to change their food habits, including:

- skipping meals

- choosing unhealthy low-cost food options over more expensive healthier options such as produce

- spending more time grocery shopping in multiple locations based on sales

- stockpiling shelf-stable food items that are on sale, when they are able to do so

- switching from culturally appropriate foods and diets to more affordable options

"All of the food that comes into our house comes from community organizations."

Many people are accessing food banks and other community-based food organizations. At food banks, staff are seeing increases in every demographic. We heard that a lot of people employed in precarious employment, people who are working poor and people receiving social assistance or disability supports are now accessing food programs.

In some cases, families and children have become reliant on school food programs for food. Places that have recently implemented school food programs have noticed reduced absenteeism as students come to school to access meals. We also heard that, days without school (such as snow days and professional development/professional activity days) can be a challenge for students who rely on school meals and have no food at home. We heard about older students bringing their kindergarten-aged siblings to school on off-kindergarten days to ensure they eat that day.

"Attendance is so low in some of these communities, but there are kids that come to school because they know they're going to get a hot breakfast."

We consistently heard that reliance on the charitable sector to provide food must end. Food banks offer temporary support, but they are not a permanent, dignified solution to food security. People feel strongly that no one should have to rely on charity to eat.

Health care and medication

"Poverty is a huge medical crisis. It affects everything."

Poverty affects physical, mental and emotional health. The trauma of poverty can push people into desperation and deeper levels of poverty. Access to physical and mental health care is important for overall well-being and for protecting people from poverty and its associated trauma.

We heard from service providers and people experiencing poverty that gaps and challenges in the health system exist, particularly for people made most marginal. Specifically, we heard about the lack of connection between shelters or correctional services and the health care system. This disconnection leaves people living in and exiting shelters without proper care, as they move from one system to another. Consequently, there is no follow-up or continuation of care, and it is during these transitions when people often "fall through the cracks."

"The justice system, the health system, etc. keep failing us."

We heard that a lack of affordable and timely transportation options to attend medical appointments can force individuals to cancel long awaited and much needed health assessments and procedures. This can result in a decline in the health status of the individual. Some new immigrants reported travelling back to their home countries to access health services because it's faster than trying to access services in Canada.

"A lot of people here go without medical care because we can't afford it."

Many of the people with lived experience in poverty shared that they faced racism within the health care system. For example, some Indigenous participants felt medical staff assumed they were just seeking drugs. Because of this bias, some say, doctors do not prescribe for them. This leads some individuals to self-medicate with street drugs.

"To me, I just feel like another dirty little Indian to them. They take me as a joke and don't take my health concerns seriously."

Finally, trepidation about the possibility of the privatization of health care among people with lived experience of poverty is real. Privatization allows people to pay for services and procedures, out of pocket or through private insurance, which many people experiencing poverty do not have. This creates unfairness, inequity and inequality by allowing some people to skip the line and prioritize themselves. Privatization would also take experience out of the public system as health professionals leave to work in private clinics. It could further strain the already overextended health care system, likely leading to even lower access for those that can't pay for private health care. Seniors in particular have greater health needs; however, many seniors cannot afford the cost of private health care.

"If there was ever private health cared, no one in this room would get it."

Transportation

Transportation is a huge challenge cited by those we met with as a barrier to accessing jobs, services, health care, healthy foods (including culturally appropriate food) and opportunities to socialize. Public transportation is offered mainly in urban centres and is often not as reliable as it should be. People living in rural areas may be entirely dependent on private transportation, which is costly, and, for some people, out of reach. In Yukon, one participant from a rural community noted that due to the lack of mechanics in most of their communities, people cannot leave the community if their car has a mechanical issue. In Newfoundland and Labrador, we heard that many people that have cars can't afford the cost of insurance, gas and maintenance, and so they need other transportation options. People with a disability have additional challenges accessing food and services because of reduced mobility and limited options for accessible transportation.

Chapter 3: Improving access to benefits and delivery of services

Policy context

Overview and data

A wide range of services, programs and benefits are in place to support people living in Canada. Governments at all levels, non-profit organizations and other front-line service providers establish and offer these services. We heard through ongoing dialogues that accessing benefits and services, however, is challenging and complex. People noted that systems are difficult to navigate and disconnected, particularly across jurisdictions, but also within and at all levels. People who would benefit most, as well as staff and volunteers supporting clients, are often not aware of what is available or how to access the services and programs.

Additionally, some groups, such as those made most marginal, are more likely to live in poverty and face challenges accessing the benefits and services they are entitled to. Systemic inequity and racism exist within systems.

Research from the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) and Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) confirms what we heard and identified several barriers to accessing benefits for hard-to-reach populations (Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2022a). These include:

- complex application processes

- the need to file a tax return

- literacy levels and/or language barriers

- the need to disclose personal and financial information to the Government

- the need to provide identification and documentation, such as a social insurance number

- living remotely

- the need to have access to financial services such as a bank account for direct deposits

Furthermore, the 2022 Auditor General of Canada's report concluded that the CRA and ESDC have not done enough to connect hard-to-reach populations with the benefits to which they are entitled (Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 2022b). These include the Canada Child Benefit, the Canada Workers Benefit, the Guaranteed Income Supplement and the Canada Learning Bond. Specifically, the report concluded that the CRA and ESDC:

- did not have a complete understanding of the eligible population that was not receiving certain benefits

- had limited evidence that their outreach activities resulted in increased benefit take-up among these groups

- did not have an approach to ensure a seamless service experience for hard-to-reach clients

The non-profit sector delivers many specific programs and services to support those living with poverty. Governments continue to download service delivery to non-profit organizations without adequate support to help these groups meet the growing demand. Non-profit organizations are strained throughout the country, as the needs of the people they serve are increasing in both quantity and complexity. For instance, CanadaHelps reported that 1 in 5 people living in Canada used charitable services to meet essential needs in 2023 (CanadaHelps, 2024). Almost 7 in 10 (69%) said this was the first time they relied on charity. This increase in demand for services and products delivered by the non-profit sector is outpacing its capacity to meet demand. Specifically, in 2023, 46.1% of non-profits reported an increased demand for services or products, while only 24.3% reported an increase in their capacity to meet demand (Statistics Canada, 2024c). Furthermore, CanadaHelps reported that 57% of charities are unable to meet current demand levels, demonstrating the gaps between increased challenges and the ability of charities to provide support (CanadaHelps, 2024).

What we heard in the ongoing dialogues

Presented below is what the Council heard from individuals who shared their expertise, experiences and opinions. The thoughts expressed do not necessarily reflect our opinions as a Council or the available data or research.

"People individualize poverty. They don't see it as a system failure but an individual moral one."

Key themes

"The real issue is that systems are built to create and perpetuate poverty."

Systems challenges are significant. Stakeholders noted that governments and organizations have built many of the systems in a different time to address challenges and populations very different from those today. These outdated systems do not always work in the current context. Some people feel they never worked at all, or worked in ways that benefited some while further marginalizing others. Some mentioned they also felt that systems are designed to perpetuate inequity and racism. Unfortunately, many don't recognize that they are caught in a system at all. They incorrectly perceive the failings of the system as personal failings. This can have negative consequences on people's self-perception, mental health and overall well-being. It can also contribute to increased stigma directed at those living with poverty.

Accessing benefits and services is stigmatized

People expressed beliefs that the way services are offered creates an unhelpful divide between people who need to access the services and those who do not. Both service users and providers describe service access points as places to go to if "there is something wrong with you." In other words, people perceive the need to access services as the result of personal issues rather than a failure of existing supports and services.

Overburdened non-profit organizations, providing much-needed support, at risk of collapse

"The government is really good at recognizing the value of the community sector but may not be as good at funding it."

We heard that non-profit organizations are undertaking a lot of work to support people experiencing poverty. We met dedicated individuals doing innovative work, building relationships and offering supports to people with complex needs, often filling gaps in the system. We saw many examples of organizations meeting people where they are and supporting more people than ever. Organizations were taking the time to establish connections, nurture relationships and build trust so individuals feel comfortable accepting help and support.

"We're all desperate for more resources. We're filling in a need that shouldn't be there."

Despite these positives, many people working in the sector are cognizant that the sector only exists because poverty exists. This creates some internal conflict, because people working in the sector perceive themselves as benefiting, through employment, from the existence of poverty. This adds to the burden and mental health load many staff experience. We heard that service providers feel they are filling a need that shouldn't exist, because poverty shouldn't exist. Multiple service providers described wanting to see a Canada in which their services are no longer required because people are properly supported.

"You are subcontracting us to do work because we are nimble and can do the work cheaper with fewer resources."

As poverty grows, the gap between need and available services widens. The ability of communities to fill those gaps becomes more difficult. We heard from many groups that feel the Government downloads responsibility for necessary programs to service organizations, often without providing adequate funding to address these expanded responsibilities.

"They tell organizations, ‘We need you to do the same work, with 2 less staff and the same amount of money and with inflation the way it is.' Organizations are working in a crisis and have to jump through hoops and break rules."

Non-profit organizations are trying to meet increasingly complex needs and are therefore doing much more than what they are funded to do. For example, organizations, particularly in rural areas, reported having to fill service gaps and increase their service offerings to meet specific needs in their communities, and these are not accounted for in funding agreements. Often, organizations need to undertake private fundraising activities to make up for the inadequate funding. These activities are time consuming and take away from their ability to provide essential services.

Service providers also described how the funding structure itself is a challenge. Programs and projects receive funding; however, this funding is targeted, limited and siloed. It may be only for one specific program or client group, and not connected to work being undertaken by other organizations. The reliance on charitable donations and grant funding also means that funders can direct where organizations focus their efforts and attention. Funders provide resources contingent on the organization using the money to address a specific issue or cater to a specific target population. We heard that organizations are so desperate for funds to maintain their projects that they expand or adjust their scope to qualify for new funding. We heard that people should not have to be concerned about who is paying for the program. They should be able to come in and get their needs met without having to worry about mandates limited by funding.

"The non-profit sector is stretched beyond its limits and is underfunded."

Further, non-profit organizations rarely receive sustained long-term funding or funding for basic operational requirements. This makes it difficult to provide holistic support to address complex needs while maintaining daily operations. Organizations described how stable funding allows them to undertake longer-term projects and innovate.

"Most people working in this area (servicing those living in poverty) don't have a living wage."

Labour shortages have hit the "helping" profession hard. The work continues to get harder, and the pay is stagnant. More people working in community organizations are needing to access the services of their workplaces, mainly because their employers, given stagnant core funding, cannot offer them living wages. This is happening during a time of increased need, meaning people are often doing more work for the same pay.

Additionally, incentives for employees in the sector to stay are few and far between. This has resulted in a lot of turnover and constant change in organizations. This leaves program recipients in the vulnerable position of having to re-establish trust and repeat their stories. It also leads to novice workers who are less experienced in doing the work. This can lead to further traumatization of program recipients or cause them to miss out on key opportunities. Adding to this pressure, non-profits are losing staff because their staff is aging. They have difficulty replacing staff either because younger individuals are not interested in the low pay, or they use it as a starter job to get some experience before moving on to higher wage jobs. This is a huge threat to the non-profit and charitable sectors in the long term. As a result, the sector is at risk of collapse.

"How do we invest in doing it differently when we can't find the people to do the work and pay them properly?"

Inadequate and limited funding, combined with outdated support systems, make it challenging for organizations to keep up with the rising demand. This has contributed to burnout in the sector. Additionally, funding accountability mechanisms, though necessary, are time consuming. Instead of focusing on service provision, organizations must divert their attention to applying for and reporting on funding grants. Funding agreements often do not account for the time spent by service providers to prepare these accountability reports. The limited number of support staff makes it difficult for many organizations to juggle both administrative and front-line responsibilities. The sector is in danger of collapse. This is problematic for the sector, for the individuals who require the services and for the federal government, which does not have the necessary welfare supports to fill in for a collapsing non-profit sector.

"Instead of looking at what is the cost of funding the social service sector, we need to flip it on its head and consider, what would be the cost of not funding our sector?"

We heard that policy-makers need to move from thinking about services as costs to seeing these as investments. Investing in people would help prevent poverty instead of reacting to it. Otherwise, the Government is paying a lot more for health care, temporary shelters, food banks, etc. Investing in people also pays off in many other ways, including fostering health, well-being and self-worth.

Some organizations noted that they spend most of their time addressing urgent matters and doing emergency work rather than focusing on prevention. They would like to shift to advocacy and education work to empower people; however, there is no time to do so. Staff are overwhelmed by the need to focus on those who are drowning instead of teaching people how to swim.

Systems are difficult to navigate

"We need to do mental gymnastics to understand the system."