Chapter 2: Impacts and Effectiveness of Employment Insurance Part I

Notice: Refer to the Table of contents to navigate through the EI Monitoring and Assessment Report .

This chapter examines the usage, impacts and effectiveness of Employment Insurance (EI) income benefits under Part I of the Employment Insurance Act.

Section I analyzes total income benefits, which combine all EI benefit types (regular, fishing, special and Work-Sharing benefits). Section II examines income support provided by EI regular benefits to individuals who lost their jobs through no fault of their own. Section III discusses EI fishing benefits paid to self-employed fishers. Section IV examines the role EI plays in helping Canadians balance work commitments with family responsibilities and personal illnesses through EI special benefits which include maternity, parental, sickness and compassionate care benefits. Section V discusses EI Work-Sharing benefits, which help employers and employees avoid temporary layoffs when normal level of business activity drop. Section VI profiles firms and their utilization (i.e., usage by their employees) of EI income benefits. Finally, Section VII provides general information on EI finances.

Unless otherwise indicated, numerical figures, tables and charts in this chapter are based on a 10% Footnote 1 sample of EI administrative data. Throughout the chapter, data for 2011/12 are compared with data from previous years and, in some instances, long-term trends are discussed. Footnote 2 More data on the benefits discussed in this chapter can be found in Annex 2. Beyond the discussion of usage (claims Footnote 3 and benefits paid Footnote 4 ), this chapter also provides different measures of EI Part I adequacy.

In this report, the main source used to examine coverage, eligibility and accessibility to EI benefits among the unemployed is Statistics Canada's Employment Insurance Coverage Survey. In addition, data from the Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics are used to explore eligibility for EI benefits among the employed population. Supplementary analysis of job separations from Records of Employment is also provided in this chapter.

This chapter also analyzes the adequacy of EI Part I benefits by reporting on various indicators including the level of, entitlement to, duration of, exhaustion of and income redistribution from benefits. The level of benefits indicates the generosity of benefits, usually expressed as the average weekly benefit. Entitlement is the maximum number of weeks of benefits payable, which varies depending on the benefit type being discussed. Duration is the average number of benefit weeks that claimants actually use. Exhaustion occurs when claimants use all the benefit weeks to which they are entitled. Finally, income redistribution transfers income from high earners to low earners and from provinces and regions of low unemployment to provinces and regions of high unemployment.

In addition, throughout the chapter, several key EI provisions and pilot projects are discussed. EI provisions are legislated, permanent features of the EI program, while pilot projects are temporary measures that modify or replace existing provisions. EI pilot projects are used to test and assess the labour market impacts of new approaches before considering a permanent change to EI. Through these provisions and pilots, the program strives to find a balance between providing adequate income benefits and encouraging work attachment. It does so by providing incentives for EI claimants to work more before establishing a claim, as well as to work while on claim.

This chapter also profiles firms and their utilization (i.e., usage by their employees) of EI income benefits. This is part of the Commission's legislated mandate to monitor how the benefits and assistance are utilized not only by employees but also by employers. Section VI uses the number of firms with employees receiving EI income benefits as an indicator of EI utilization by employers. It also analyzes these firms to establish the extent to which their employees are receiving EI income benefits. These two indicators are then examined in further detail: first, by surveying the utilization of EI income benefits since 2004, to better understand the late-2000s recession from the perspective of firms; and, second, by considering the utilization of EI regular benefits in relation to various categories, including the location of a firm's headquarters, firm size and within industries. Finally, the benefits-to-contributions ratio is discussed for these categories.

For a detailed qualitative overview of the EI program, including information on eligibility requirements and the calculation of benefits, as well as EI provisions and pilot projects, please see Chapter 1 of the 2011 EI Monitoring and Assessment Report at:

http://www.hrsdc.gc.ca/eng/jobs/ei/reports/mar2011/chapter1.shtml

1. Economic Action Plan 2012

Economic Action Plan 2012 announced a number of changes to the EI program. Footnote 5 First, the Government of Canada has committed new investments over two years to better connect unemployed Canadians with available jobs in their local area. Along with providing relevant and timely job information, the government has updated the EI Regulations to clarify claimants' responsibilities to undertake a reasonable job search for suitable employment while receiving EI regular or fishing benefits.

Second, the government has introduced a new, permanent and legislated approach to the way EI benefits are calculated. Effective April 2013, EI claimants, with the exception of fishing and self-employed claimants, will have their EI benefit amounts calculated based on the weeks of their highest insurable earnings during the qualifying period, which is generally 52 weeks. The number of weeks used to calculate benefit rates will range from 14 to 22, depending on the unemployment rate in the EI economic region where the claimant resides. The new approach will make the EI program more responsive to changes in local labour markets and will ensure that those living in similar labour markets receive similar benefits. While the new approach is put into place, the Best 14 Weeks pilot project has been extended in 25 EI economic regions.

Third, the new Working While on Claim (WWC) pilot project reduces a claimant's benefits by 50% of his or her earnings while on claim, starting with the first dollar earned. This new pilot project will ensure that EI claimants always benefit from accepting more work and supporting their search for permanent employment. There is a degree of flexibility to this provision. Some claimants who had earnings between August 7, 2011 and August 4, 2012, and were eligible to benefit from the WWC pilot project rules, have the option of reverting to the rules of the previous WWC pilot project. Under the old rules, claimants were allowed to earn $75 or 40% of their EI benefits, whichever was greater. After they reached that threshold, this was followed by a 100% clawback of benefits for all additional earnings.

Fourth, the government will limit rate increases to no more than 5 cents each year until the EI Operating Account is balanced. Once the account has achieved balance, the EI premium rate will be set annually at a seven-year break-even rate to ensure that EI premiums are no higher than needed to pay for the EI program. After the seven-year rate is set, annual adjustment to the rate will also be limited to 5 cents.

Lastly, a new Social Security Tribunal (SST) will become operational on April 1, 2013. The goal of the new SST is to establish a more streamlined, responsive and efficient administrative justice system that will operate coherently across all major federal social security programs. However, as these modifications were not implemented in 2011/12, the reference year for this report, their impacts and effectiveness will be discussed in future M&A reports.

I. TOTAL INCOME BENEFITS

In 2011/12, the total number of new EI claims increased slightly relative to 2010/11. However, the on-going economic recovery, coupled with the end of the temporary EI measures, resulted in a decrease in total EI benefit payments.

1. Total Income Benefits, Claims and Benefit Payments

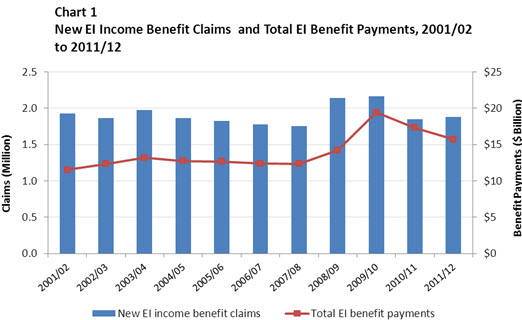

In 2011/12, the total number of new EI income benefit claims increased by 2.0% (+36,830), from 1.85 million in 2010/11 to 1.88 million. As illustrated in Chart 1, the total number of new EI claims reached 2.16 million in 2009/10, the highest volume since 2000/01 as a result of the late-2000s recession.

The increase in claims in 2011/12 was driven by a 1.8% (+25,410) increase in EI regular benefits claims, a 1.8% (+9,230) increase in EI special benefits claims, a 3.4% (+973) increase in EI fishing benefits claims and an 11.7% (+2,675) increase in EI Work-Sharing benefits claims.

Table equivalent of Chart 1

| Year | New EI income benefit claims (Million) | Total EI benefit payments ($ Billion) |

|---|---|---|

| 2001/02 | 1.93 | $11.5 |

| 2002/03 | 1.87 | $12.3 |

| 2003/04 | 1.97 | $13.2 |

| 2004/05 | 1.86 | $12.7 |

| 2005/06 | 1.83 | $12.7 |

| 2006/07 | 1.78 | $12.4 |

| 2007/08 | 1.76 | $12.3 |

| 2008/09 | 2.14 | $14.2 |

| 2009/10 | 2.17 | $19.4 |

| 2010/11 | 1.85 | $17.3 |

| 2011/12 | 1.88 | $15.7 |

In contrast to the increase in the number of total EI claims, total EI benefit payments declined by 9.4% (-$1.6 billion), from $17.3 billion in 2010/11 to $15.7 billion in 2011/12, after a decrease of 10.8% (-$2.11 billion) in 2010/11. Despite these declines, EI benefits paid in 2011/12 were still significantly higher than what was paid before the late-2000s recession. Specifically, in comparison to 2007/08, total income benefits were 27.3% higher in 2011/12.

The decline in total EI benefit payments between 2010/11 and 2011/12 was largely driven by a 12.9% decline (from $12.3 billion in 2010/11 to $10.7 billion in 2011/12) in regular benefit payments as the result of the on-going economic recovery and the conclusion of the temporary EI measures introduced in response to the late-2000s recession. As shown in Chart 2, regular benefits accounted for 68.2% of total income benefits paid in 2011/12, decreasing slightly from 71.0% in the previous year (-2.8 percentage points). More detailed information on total income benefits can be found in Annex 2.1.

| Type of EI Benefit | Claims |

|---|---|

| EI Regular Benefits | 1,422,270 |

| EI Special Benefits Footnote 6 | 508,500 |

| EI Parental Benefits | 188,930 |

| EI Sickness Benefits | 331,220 |

| EI Maternity Benefits | 167,540 |

| EI Compassionate Care Benefits | 5,975 |

| EI Fishing Benefits | 29,506 |

| EI Work-Sharing Benefits | 23,755 |

| Total Footnote 7 | 1,883,600 |

Table equivalent of Chart 2

| Regular Benefits | $10,707.81 |

|---|---|

| EBSM Participants | $413.7 |

| Work-Sharing Benefits | $31.7 |

| Fishing Benefits | $259.2 |

| Special Benefits | |

| Parental Benefits | $2,222.04 |

| Sickness Benefits | $1,117.26 |

| Maternity Benefits | $933.6 |

| Compassionate Care Benefits | $10.9 |

In comparison to regular benefits, special benefits tend to be less sensitive to economic cycles, and more sensitive to demographic shifts and to changes in labour force characteristics. In 2011/12, EI special benefit payments increased slightly, from $4.18 billion in 2010/11 to $4.28 billion in 2011/12 (+2.5%). EI parental benefit payments accounted for the largest share (51.9%) of EI special benefit payments. EI special benefit payments represented 27.3% of total EI income benefits paid.

Payments for all other types of benefits, such as EI fishing benefits, EI Work-Sharing benefits, and EI Part I payments to Employment Benefits and Support Measures (EBSMs) participants, comprised 4.5% of total EI income benefits payments. Although these three benefit payments declined as a whole by 17.2% in 2011/12, they remained 4.0% higher than what was paid in 2007/08. More detailed information on EBSMs can be found in Chapter 3.

1.1 Total Income Benefits Claims, by Province and Territory

Provincial and territorial labour markets vary in their demographic and sectoral composition. As shown in Table 2, the provincial/territorial distribution of EI claims does not necessarily align with their distribution of employees. For example, the Atlantic provinces accounted for 15.4% of total EI claims in 2011/12, but accounted for 6.6% of all employees, Footnote 8 representing the largest percentage-point difference between the share of EI claims and the share of employees. Ontario and Quebec had the largest shares of employees, with Ontario accounting for 38.3% of national employment and Quebec accounting for 22.8%. These two provinces also had the largest shares of total EI claims, with 31.5% and 27.9%, respectively.

| Province or Territory | % of Total EI Claims | % of Employees | % of Total Benefit Payments | Average Weekly Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 4.6 | 1.4 | 5.7 | $394 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1.3 | 0.4 | 1.4 | $381 |

| Nova Scotia | 4.7 | 2.7 | 5.1 | $377 |

| New Brunswick | 4.9 | 2.1 | 5.4 | $370 |

| Quebec[2] | 27.9 | 22.8 | 22.7 | $378 |

| Ontario | 31.5 | 38.3 | 33.1 | $382 |

| Manitoba | 3.1 | 3.8 | 2.9 | $368 |

| Saskatchewan | 2.3 | 3.1 | 2.4 | $392 |

| Alberta | 7.6 | 12.2 | 8.6 | $410 |

| British Columbia | 11.8 | 12.8 | 12.1 | $377 |

| Nunavut | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | $439 |

| Northwest Territories | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | $449 |

| Yukon | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | $443 |

| Canada | 100 | 100 | 100 | $382 |

[1] Statistics Canada, Employment, Earnings and Hours (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, monthly), Cat. No. 72-002-XIB.

[2] Quebec claims do not include claims for maternity and parental benefits, as the province has its own program—the Quebec Parental Insurance Plan (QPIP)—to provide such benefits.

In 2011/12, total benefits payments declined in seven provinces and territories, with the largest declines occurring in Alberta (-17.1%, -$278.2 million) and British Columbia (-14.3%, -$318.3 million). Although the other six provinces and territories recorded increases in total benefits payments from 2010/11, the increases were not significant. The sharpest increases in total benefits payments occurred in the Northwest Territories (+4.1%, +$1.3 million) and Yukon (+2.3%, +$0.7 million).

In 2011/12, average weekly benefit rates increased in every province and territory. The most notable increases took place in Newfoundland and Labrador (+$17, +4.6%), Saskatchewan (+$16, +4.2%) and Nova Scotia (+$14, +4.0%). The increases observed in the provincial and territorial average weekly benefit rates were in line with the increases in average weekly earnings, as discussed in Chapter 1. Provincial and territorial average weekly benefit rates ranged from $368 in Manitoba to $449 in the Northwest Territories, with the highest average weekly benefit rates in the three territories.

1.2 Total Income Benefits Claims, by Gender and Age

The number of claims established by women increased by 22,220 in 2011/12 (+2.7%), following a decrease of 100,380 in 2010/11 (-10.7%). The number of claims established by men rose by 14,610 (+1.4%), after a significant decline in 2010/11 of 218,290 claims (-17.8%).

The increase in EI claims for women was partly due to the 2.8% increase in the number of claims established in the services-producing sector, where women tend to be over-represented (women represented 54.7% of workers in the sector in 2011/12). Footnote 9

As indicated in Chart 3, during the late-2000s recession, the proportion of total EI claims established by men increased significantly, from 53.9% in 2007/08 to 57.6% in 2008/09. Correspondingly, the proportion of total EI claims established by women decreased from 46.1% to 42.2% during the same period. This is attributable to the fact that the late-2000s recession had a relatively greater impact on industries in the goods-producing sector, such as manufacturing and construction, where men are over-represented (for example, in 2011/12, men accounted for 71.2% and 88.9% of employment in those sectors, respectively). As the recovery took hold, the proportions of total EI claims established by both women and men slowly returned to their pre-recession levels.

Table equivalent of Chart 3

| Proportion, by Gender | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GENDER | 2000/01 | 2001/02 | 2002/03 | 2003/04 | 2004/05 | 2005/06 | 2006/07 | 2007/08 | 2008/09 | 2009/10 | 2010/11 | 2011/12 |

| Male | 54.6% | 54.7% | 54.5% | 54.2% | 53.2% | 53.2% | 54.1% | 53.9% | 57.6% | 56.7% | 54.7% | 54.4% |

| Female | 45.4% | 45.3% | 45.5% | 45.8% | 46.8% | 46.8% | 45.9% | 46.1% | 42.4% | 43.3% | 45.3% | 45.6% |

Total benefits paid to men decreased by 12.1% in 2011/12, after decreasing by 17.0% in the previous fiscal year, while total benefits paid to women fell by 6.2% in 2011/12, after a decrease of 2.6% in the previous year. Despite an overall decline in 2011/12, total benefits paid remained significantly higher than pre-recession levels (28.9% higher for men and 25.5% higher for women in comparison to 2007/08).

Between 2010/11 and 2011/12, the unemployment rate fell across all three major age groups. However, only youth (aged 15 to 24 years) registered a decline of 6.3% (-13,800) in the total number of EI claims established. Total EI claims for core-aged workers (aged 25 to 54) and older workers (aged 55 years and older) increased by 18,260 (+1.4%) and 32,370 (+10.5%), respectively. In comparison to pre-recession levels in 2007/08, the claim volume was higher for all age groups (+0.5% for youth, +3.2% for core-aged workers and +32.1% for older workers). The larger increase in claim volume among older workers is likely attributable to the lingering effects of the late-2000s recession, as the precarious financial climate caused some older workers to either re-enter the labour market to earn additional income or postpone retirement until the economy strengthens significantly.

2. Income Redistribution from Income Benefits

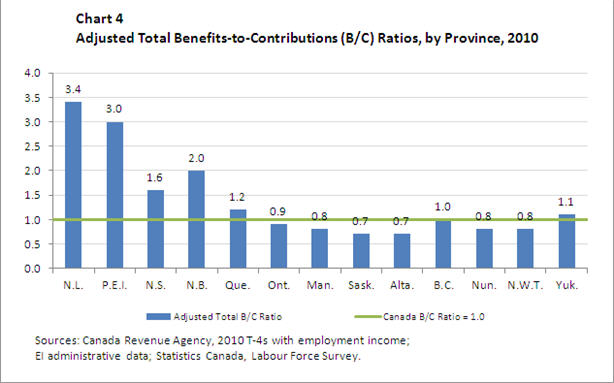

To measure the extent of redistribution for total EI income benefits, the amount of EI benefit payments received in each province/territory, industry or demographic group is divided by the total amount of EI premiums collected, which constitute the benefits-to-contributions (B/C) ratio. The amount of EI premiums collected is based on the latest Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) tax data available, which are for 2010. EI benefit data used for this analysis of B/C ratios are therefore for 2010 as well. These ratios are then normalized, so that the ratio for Canada is equal to 1.0. The resulting ratio for each group indicates whether the province/territory, industry or demographic group receives more in EI benefits than it contributes to the program, relative to Canada as a whole.

A province/territory, industry or demographic group with an adjusted ratio higher than 1.0 is a net beneficiary of the EI program while those with an adjusted ratio lower than 1.0 are net contributors to the program within the Canadian context. Annex 2.19 provides a detailed account of EI premiums paid and regular benefit payments received across different provinces and territories, industries, and demographic groups.

2.1 Benefits-to-Contributions Ratios, by Province and Territory

The Atlantic provinces and Quebec continued to be net beneficiaries of EI total income benefits in 2010, as they were in previous years, with adjusted ratios greater than 1.0, while Ontario and the Prairie provinces remained net contributors, with adjusted ratios below 1.0 (see Chart 4).

Table equivalent of Chart 4

| Province | Adjusted Total B/C Ratio |

|---|---|

| N.L. | 3.4 |

| P.E.I. | 3.0 |

| N.S. | 1.6 |

| N.B. | 2.0 |

| Que. | 1.2 |

| Ont. | 0.9 |

| Man. | 0.8 |

| Sask. | 0.7 |

| Alta. | 0.7 |

| B.C. | 1.0 |

| Nun. | 0.8 |

| N.W.T. | 0.8 |

| Yuk. | 1.1 |

| Canada | 1.0 |

2.2 Benefits-to-Contributions Ratios, by Industrial Sector

In 2010, the goods-producing sector was a net beneficiary of EI benefits, with an adjusted regular benefits-to-contributions ratio of 1.6, while the services-producing sector was a net contributor of EI benefits, with an adjusted ratio of 0.8 (see Chart 5).

Table equivalent of Chart 5

| Sector | Ratio |

|---|---|

| Goods-producing industries | 1.6 |

| Construction | 2.1 |

| Manufacturing | 1.3 |

| Services-producing industries | 0.8 |

| Wholesale trade | 1.0 |

| Retail trade | 0.8 |

| Finance and insurance | 0.6 |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 0.8 |

| Administrative and support services | 1.4 |

| Educational services | 0.8 |

| Health care and social assistance | 0.6 |

| Accommodation and food services | 1.2 |

| All industries | 1.0 |

2.3 Benefits-to-Contributions Ratios, by Gender and Age and Income

Men and women were neutral in their usage of EI income benefits, according to the adjusted benefits-to-contributions ratios for EI income benefits, as they both had a ratio of 1.0.

Among different age groups, claimants aged 25 to 44 had a ratio of 1.1, as they made up the majority of maternity and parental benefit recipients. Youth also showed a benefits-to-contributions ratio of 1.1. Claimants aged 55 and older had a benefits-to-contributions ratio of 1.0, even though their 2011/12 claim volume was 32.1% higher than their pre-recession volume of 2007/08.

A study on the financial impact of receiving EI Footnote 10 concludes that low-income families have a higher benefits-received-to-contributions ratio than high-income families do. In fact, families with after-tax income below the median received 34% of total benefits and paid 18% of all premiums. Moreover, an evaluation study, Footnote 11 using the Longitudinal Administrative Database, found that the distributional impact of EI increased substantially during the late-2000s recession.

3. Family Supplement Provision

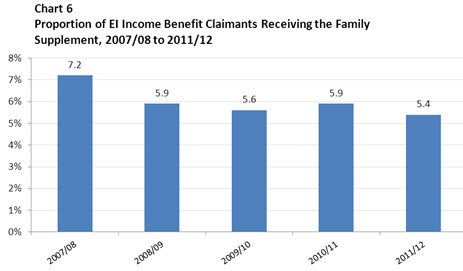

The Family Supplement provides additional benefits to low-income families with children, Footnote 12 giving eligible claimants a benefit rate of up to 80% of their average weekly insurable earnings and is available for all benefit types. In 2011/12, a total of 101,130 claims qualified for the Family Supplement, a decrease of 7.7% from the previous year. The average weekly top-up increased to $42.69, from $42.31 in the previous year. More detailed information on the Family Supplement can be found in Annex 2.15.

Table equivalent of Chart 6

| Year | Proportion of EI income benefit claimants receiving the Family supplement |

|---|---|

| 2007/08 | 7.2% |

| 2008/09 | 5.9% |

| 2009/10 | 5.6% |

| 2010/11 | 5.9% |

| 2011/12 | 5.4% |

Women are more likely than men to receive the Family Supplement top-up. In 2011/12, women represented 77.7% of Family Supplement recipients, similar to the previous year (77.5% in 2010/11).

In 2011/12, low-income families received $112.6 million in additional benefits through the Family Supplement, a decrease of 13.2% from the previous year. Family Supplement payments decreased for both genders and for all age groups in 2011/12, with men (-17.7%) and claimants aged 55 years and older (-16.9%) experiencing the largest declines.

The proportion of all EI claimants receiving the Family Supplement top-up decreased from 5.9% in 2010/11 to 5.4% in 2011/12. The proportion of claimants receiving the Family Supplement top-up has been dropping over the past decade, as illustrated by Chart 6. The overall decline in the share of these claims is due largely to the fact that the Family Supplement threshold has been held constant while family incomes have continued to rise.

In general, recipients of the Family Supplement top-up are entitled to fewer weeks of regular benefits than non-recipients are but collect more weeks of regular benefits and use a higher percentage of their entitlement. Among claims established in 2010/11, Footnote 13 Family Supplement recipients were entitled to an average of 33.2 weeks of EI benefits, while non-recipients were entitled to 36.7 weeks. However, Family Supplement recipients used 7.8 more weeks of EI benefits, on average, than non-recipients did (31.3 weeks and 23.5 weeks, respectively). While the number of claimants receiving the Family Supplement top-up has been on the decline, this analysis suggests that recipients of the supplement rely on EI benefits more than non-recipients do and that the top-up continues to provide important additional temporary income support for low-income families.

4. Premium Refund Provision

The EI program has specific provisions for contributors who are unlikely to qualify for benefits. Employees with insured earnings of less than $2,000 are entitled to a refund of their EI premiums when they file an income tax return.

According to Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) T-4 data from employers, 1.1 million individuals had insured earnings of less than $2,000 and were eligible for an EI premium refund in 2010, representing 6.4% of those in paid employment.

In addition, an evaluation study Footnote 14 using CRA T-1 data from individual tax-filers found that, in 2010, there were 610,000 individuals that received the EI premium refund, with an average refund of $16.40 per individual.

5. EI Support for Apprentices

Apprenticeship is the key means by which individuals gain the skills they need in order to be certified in the skilled trades. In 2010, approximately 2.9 million Canadians worked in skilled trades that were designated for apprenticeship training, representing 17% of the labour force. The duration of apprenticeship programs can range from two to five years, depending on the trade and jurisdiction.

Apprenticeship is a structured system composed primarily of supervised on-the-job training supported by shorter periods of intensive, in-class technical instruction, during which apprentices develop new skills and knowledge, which they can use immediately in the workplace. In many apprenticeship programs, these in-class technical training periods alternate with the on-the-job work training component for several weeks (6-8 weeks is the norm for block training). The EI program facilitates apprenticeship training by providing EI regular benefits to apprentices during periods of block classroom training.

In 2011/12, a total of 40,110 new apprenticeship claims were established, which represented an increase of 4.5% from the previous year. Total benefits paid to apprentices decreased by 2.6%, from $172.3 million in 2010/11 to $167.8 million in 2011/12. However, apprentices received a higher average weekly benefit than the average EI claimant ($428 vs. $382).

Typically, apprenticeship claimants are male, are younger than 45 and work in the construction industry. In 2011/12, almost all apprenticeship claimants were younger than 45 (97.1%), with just under half (49.7%) being under 25 years old. Furthermore, men made 96.3% of all apprenticeship claims in 2011/12.

The construction industry is traditionally over-represented in the number of new apprenticeship claims. In 2011/12, this industry accounted for 55.3% of all new apprenticeship claims, while manufacturing, which had the next highest share, accounted for 8.7%.

While apprentices tend to have an entitlement similar to that of other EI claimants, they use fewer weeks of benefits, which is consistent with the relatively short duration of in-class apprenticeship training. In 2011/12, apprenticeship claims had an average entitlement of 35.3 weeks, slightly higher than that of non-apprenticeship claims (33.1 weeks). However, the average duration of apprenticeship claims was 10.1 weeks, compared with 20.1 weeks for non-apprenticeship claims.

6. Economic Action Plan Temporary EI Measures

As of March 31, 2012, over 1.5 million claimants Footnote 15 had received $3.4 billion in additional benefits as a result of the temporary EI measures from the Economic Action Plan of the Canadian federal budget for the 2009/10 fiscal year.

The Extension of EI Regular Benefits provided 5 extra weeks of regular EI benefits for all individuals with an active claim between March 1, 2009, and September 11, 2010. For these individuals, the number of weeks of benefits payable ranged from 19 to 50, rather than 14 to 45, depending on the number of insurable hours in the qualifying period and the unemployment rate in the region where the claim was established.

The Extension of EI Benefits for Long-Tenured Workers allowed EI-eligible claimants who met the long-tenured worker definition Footnote 16 and who established their claim between January 4, 2009, and September 11, 2010, to be eligible for up to 20 weeks of additional benefits, depending on how long they had been working and paying into EI.

The Career Transition Assistance (CTA) Initiative offered displaced long-tenured workers the opportunity to receive earlier or extended EI regular benefits if they undertook longer-term training early in their claim. The temporary measures included the Extended Employment Insurance and Training Incentive (EEITI) pilot project and the Severance Investment for Training Initiative (SITI). Provinces and territories were responsible for approving clients for training.

The EEITI increased the duration of EI Part I income support offered to long-tenured workers pursuing significant training, up to a maximum of 104 weeks (including the two-week waiting period). This extension included up to 12 consecutive weeks of EI regular benefits following the completion of training to facilitate job search and re-employment.

The SITI allowed earlier access to EI Part I regular benefits for eligible claimants who invested in their own training, using all or part of their severance package. SITI participants who met the eligibility requirements of the EEITI were able to participate in both measures.

Changes to the Work-Sharing Program temporarily eased the requirements for the recovery plan, streamlined the application process for employers and extended the maximum duration of agreements. Changes introduced as part of Budget 2009 extended Work-Sharing agreements by 14 weeks to a maximum of 52 weeks for applications received between February 1, 2009, and April 3, 2010. Budget 2010 further extended existing or recently terminated agreements for up to an additional 26 weeks, to a possible maximum of 78 weeks, and maintained the flexibility in qualifying criteria for new Work-Sharing agreements. These Budget 2010 enhancements were in place until April 2, 2011. Budget 2011 announced a new temporary measure to assist employers who continued to face challenges. It made available an extension of up to 16 weeks for active or recently terminated Work-Sharing agreements. This temporary measure ended in October 2011. In addition, Budget 2011 announced new policy adjustments to make the program more flexible and efficient for employers. These new provisions include a simplified recovery plan, more flexible utilization rules and technical amendments to reduce administrative burden.

| 2008/09 | 2009/10 | 2010/11 | 2011/12 | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extension of EI Regular Benefits | Claims Impacted | 87,050 | 561,600 | 563,690 | 87,120 | 1,299,460 |

| Benefits Paid ($ Million) | 82.3 | 847.2 | 848.3 | 143.6 | 1,921.3 | |

| Extension of EI Benefits for Long-Tenured Workers | Claims Impacted | N/A | 61,440 | 128,360 | 31,310 | 221,110 |

| Benefits Paid ($ Million) | N/A | 196.7 | 635.4 | 174.0 | 1,008.0 | |

| Career Transition Assistance | Claims Impacted | N/A | 7,874 | 2,401 | 450 | 10,725 |

| Benefits Paid ($ Million) | N/A | 14.7 | 80.6 | 19.3 | 114.6 | |

| Work-Sharing Footnote 17 | Benefits Paid ($ Million) | N/A | 206.3 | 78.6 | 25.4 | 310.3 |

As of March 31, 2012, a total of 1,299,460 claims Footnote 18 had benefited from the Extension of EI Regular Benefits temporary measure and had been completed. Of that number, 75.7% (2008/09), 81.0% (2009/10) and 78.1% (2010/11) received the full five weeks that were available for them.

As the automatic increase in entitlement raised the average regular benefit entitlement by 2.4 weeks to 32.3 weeks in 2011/12, the introduction of the Extension of EI Regular Benefits and the Extension of EI Benefits for Long-Tenured Workers temporary measures increased the regular benefit entitlement by almost an additional 4 weeks, to an average of 36.0 weeks.

The average duration of regular benefits for these claims was 28.7 weeks in 2008/09, 34.0 weeks in 2009/10, Footnote 19 36.7 weeks in 2010/11 and 41.2 weeks in 2011/12. In addition, these claims were associated with, on average, 4.5 weeks of the additional 5 weeks available in 2008/09, 4.6 weeks in 2009/10, 4.5 weeks in 2010/11, and 4.3 weeks in 2011/12.

As of March 31, 2012, a total of 221,100 claims from long-tenured workers Footnote 20 had benefited from the Extension of EI Benefits for Long-Tenured Workers temporary measure and had been completed. Of these claims, 66.3% received all the additional weeks that were available to them in 2009/10 and and 47.9% did so in 2010/11, while 53.4% received all additional weeks available to them in 2011/12.

The average duration of regular benefits for these claims was 49.7 weeks in 2009/10, 50.9 weeks in 2010/11 and 51.7 weeks in 2011/12. In addition, these claims were associated with, on average, 13.7 weeks of their additional regular entitlement in 2009/10, 11.0 weeks in 2010/11 and 10.2 weeks in 2011/12.

A recent study Footnote 21 on the impact of the Extension of EI Regular Benefits temporary measure shows that the number of weeks of overall entitlement negatively affected the probability of using the additional weeks of benefits provided under the Extension of EI Regular Benefits. For instance, 50.2% of claimants with a maximum of 25 weeks of entitlement used at least 1 of the 5 additional weeks available to them, while only 24.5% of claimants with 41 to 50 weeks of entitlement used the additional weeks of regular benefits.

Another study Footnote 22 on the Extension of EI Benefits for Long-Tenured Workers temporary measure reveals that the more additional weeks long-tenured workers were entitled to, the more likely they were to use them. For instance, long-tenured workers who were entitled to 8 to 20 additional weeks of regular benefits were more likely to use at least some of their additional weeks than those who were entitled to only 5 additional weeks under this temporary measure.

Recent evaluation studies find similar results in terms of the positive effect that both of the temporary measures had on the exhaustion rate of claimants who qualified for additional weeks of regular benefits. For instance, a recent evaluation study Footnote 23 estimates that the Extension of EI Regular Benefits temporary measure decreased the probability of entitlement exhaustion by 4.8 percentage points. Another evaluation study Footnote 24 finds that among long-tenured workers who qualified for additional weeks of regular benefits under the Extension of EI Benefits for Long-Tenured Workers temporary measure, only 17.1% exhausted their benefit entitlement. According to this study, this exhaustion rate was about half the rate (29.6%) recorded for non-long-tenured workers. The evaluation also finds that the exhaustion rate for long-tenured workers ranged from a high of 33.3% for claimants entitled to a total of 26 to 30 weeks of regular benefits to a low of 11.4% for claimants entitled to a total of 66 to 70 weeks of regular benefits.

Page details

- Date modified: