The threat from within: SS Caribou sunk during Battle of the St. Lawrence

Navy News / October 14, 2020

Tremendous explosions shook houses and awakened the inhabitants of a small fishing village off the Gaspé Peninsula in Québec over the night of May 11-12, 1942.

German submarine U-553, lying in ambush in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, had torpedoed two Dutch freighters, Nicoya and Leto. There were 18 casualties and 123 survivors.

A threat that no-one had dared mention until then had just materialized: German U-boats were in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Nazi Germany was threatening Canada from within.

During 1942, German submarines reigned supreme during the Battle of the Atlantic. U-boat wolf packs ravaged Allied convoys, sinking more vessels than the Allies could build. The United States’ entry into the war brought even more German submarines to the east coast of North America.

Eventually they made their way into Canadian territorial waters, giving rise to a battle that is still little known both inside and outside Canada: the Battle of the St. Lawrence.

This battle, which saw German U-boats enter the waters of the Cabot Strait and the Strait of the Belle Isle, was the first time since 1812 that enemy ships had been responsible for casualties within Canada’s inland waters. This battle brought the Second World War, which had felt distant or even remote, to our country’s doorstep.

Between 1942 and late 1944, 16 German U-boats fired more than 50 torpedoes, sinking 24 ships, including three Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) warships: His Majesty’s Canadian Ships (HMCS) Raccoon and Shawinigan, which lost all hands, and HMCS Charlottetown, which lost 10 sailors.

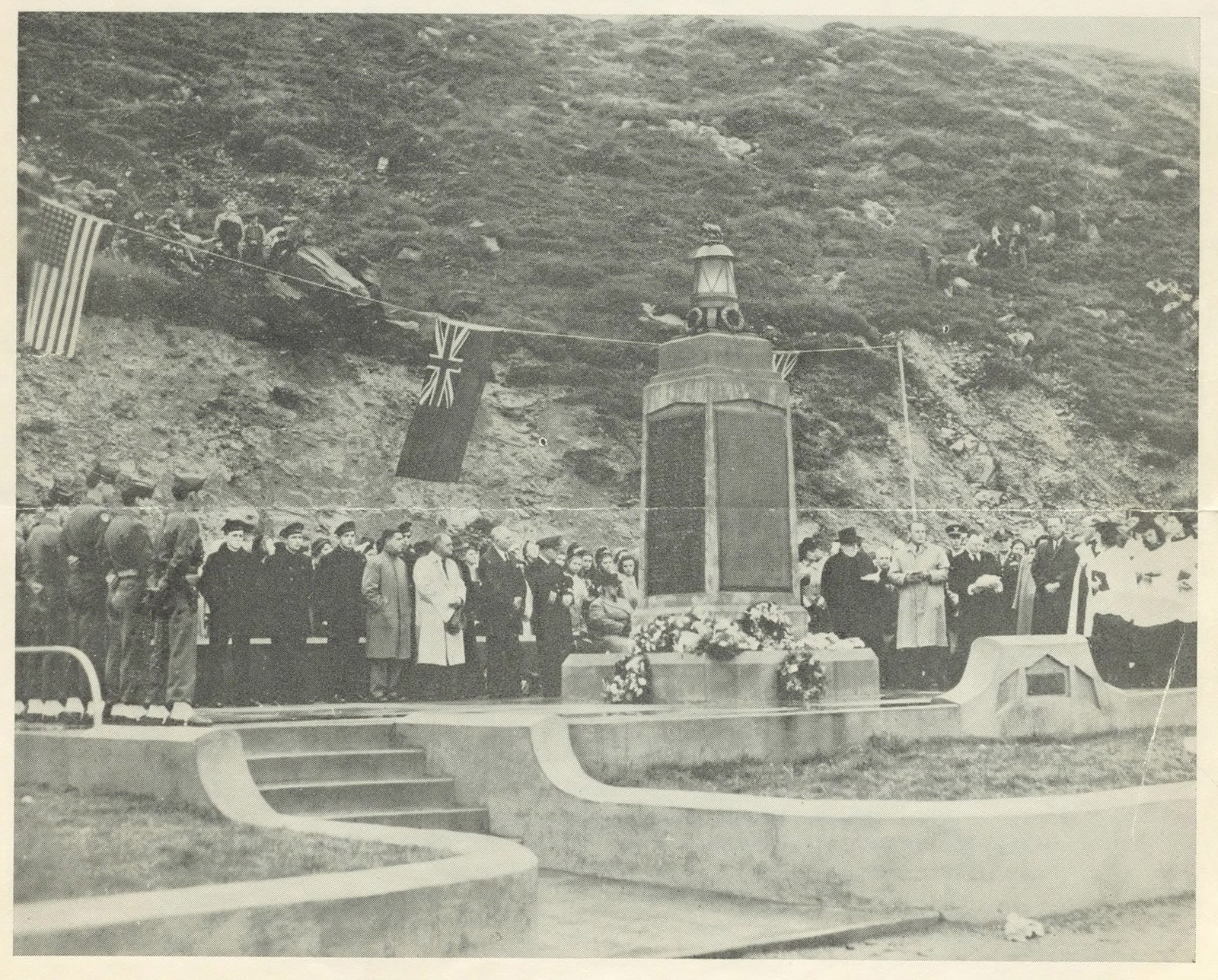

The greatest loss of life however, occurred on October 14, 1942, when the Newfoundland to Nova Scotia ferry SS Caribou was sunk by U-69, under the command of Kapitän-Leutnant Ulrich Gräf.

SS Caribou left Sydney, N.S., at approximately 9:30 p.m., on October 13, 1942. On board were 73 civilians, including 11 children, 118 military personnel and a crew of 46.

Just before departure, Caribou’s master, Captain Benjamin Tavenor, ordered all passengers on deck to familiarize themselves with the lifeboat stations. Both he and his crew knew about the danger of a U-boat attack – on the previous trip Caribou’s escort had attacked a contact, but without success.

Escorting Caribou on this trip was the RCN minesweeper, HMCS Grandmère. The night was dark with no moon. Grandmère’s skipper, Lieutenant James Cuthbert, was unhappy about both the amount of smoke Caribou was making and his screening position off Caribou’s stern, which was in accordance with British naval procedures for a single escort.

Cuthbert believed the best place for Grandmère to be was in front of Caribou, not behind. He felt he would be better able to detect the sound of a lurking U-boat if he had a clear field in front to probe.

He was correct, for directly in Caribou’s path lay U-69.

Gräf had actually been searching for a three-ship grain convoy heading for Montréal when at 3:21 a.m. he spotted Caribou belching heavy smoke about 60 kilometres off the coast of Newfoundland.

He misidentified the 2,222-ton Caribou and the 670-ton Grandmère as a 6,500-ton passenger freighter and a two-stack destroyer. At 3:40 a.m., a lone torpedo hit Caribou on its starboard side.

Pandemonium ensued as passengers, thrown from their bunks by the explosion, rushed topside to the lifeboat stations. For some reason, several families had been accommodated in separate cabins and now sought each other in the confusion.

In addition, several lifeboats and rafts had either been destroyed in the explosion or could not be launched. As a result, many passengers were forced to jump overboard into the cold water.

Meanwhile, Grandmère had spotted U-69 in the dark and turned to ram. Gräf, still under the impression he was facing a destroyer rather than a minesweeper, crash dived. As Grandmère passed over the swirl left by the submerged submarine, Cuthbert fired a diamond pattern of six depth charges.

Gräf, meanwhile, headed for the sounds of the sinking Caribou, knowing that the survivors left floating on the surface would inhibit Grandmère from launching another attack. However, U-69’s manoeuvre went unnoticed by Grandmère and Cuthbert dropped another pattern of three charges. Gräf fired a decoy and slowly left the area.

At 6:30 a.m., Grandmère gave up the hunt and started to pick up survivors. Of the 237 people aboard Caribou when it left Sydney, 101 were rescued and 136 perished.

News of the sinking sparked much outrage as victims’ friends and families, and the population at large, condemned the Nazis for targeting a passenger ferry. An editorialist with The Royalist newspaper in St. John’s wrote that the sinking “was such a useless crime from the point of view of warfare. It will have no effect upon the course of the war except to steel our resolve that the Nazi blot on humanity must be eliminated from our world.”

Although the St. Lawrence River was never a major target for German strategists, it was the site of continued sporadic U-boat attacks. Neither the number of ships sunk nor the closure of the St. Lawrence provided any strategic gain to the Third Reich.

Of the 2,500 vessels sunk during the Battle of the Atlantic, 23 (including three warships) were sunk by half a dozen U-boats in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

The Battle of the St. Lawrence was ultimately won in the Atlantic.

Page details

- Date modified: