The RCAF Flyers stunned the world by winning Olympic gold

News Article / February 8, 2018

Click on the photo under “Image Gallery” to see more photos.

By Joanna Calder

February 8, 2018, is the 70th anniversary of the Royal Canadian Air Force Flyers’ historic Olympic win. The hastily-assembled hockey team came from nowhere to defeat the world favourites at the 1948 Olympic Winter Games and bring home the gold medal.

It was September 8, 1947, and Squadron Leader Alexander “Sandy” Watson, the Royal Canadian Air Force’s senior medical officer, was appalled.

Earlier that year, the International Olympic Committee had announced that “amateur” status for Olympic athletes would be strictly enforced and that anyone who had received any kind of financial benefit from playing sports – even if it was a stipend (an allowance in lieu of a salary) rather than an actual salary – would not be eligible to compete. That meant that the winners of the Allan Cup, who were normally selected to represent Canada in the hockey competition, wouldn’t be able to play.

In light of this change in rules, Canada wouldn’t be sending a hockey team to the 1948 Winter Olympics in St. Moritz, Switzerland. Squadron Leader Watson thought this was unacceptable and started telephoning people.

Within 24 hours he had obtained the support of Defence Minister Brooke Claxton, Air Marshal Wilf Curtis, chief of the air staff, and the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association for his idea of forming a Royal Canadian Air Force hockey team to compete in the Olympics. Because RCAF personnel were paid for their military work, and not their participation in sports, they met the definition of amateur.

That was the easy part. Next came the tough part – putting together a team!

Tryouts and practices for the RCAF Flyers hockey team began immediately. Unfortunately, three of the RCAF’s top hockey players, the members of the so-called Kraut Line – Robert Theodore “Bobby” Bauer, Milton Conrad “Milt” Schmidt and Woodrow Clarence “Woody” Dumart – were ineligible because they’d played for the Boston Bruins before the war. But there were lots of other great hockey players in the RCAF, and after a number of long, gruelling days a team was assembled.

They were terrible! In their first official exhibition game, against the McGill University Redmen, the Flyers were beaten 7-0 in front of a huge crowd that included the Governor General, Defence Minister Claxton, Air Marshal Billy Bishop, and representatives of the Canadian Olympic Association and the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association. Two days later, they were again defeated by the Canadian Army hockey team. Squadron Leader Watson and the team’s coach, Sergeant Frank Boucher, went back to the drawing board.

Finally, by January 7, 1948, a strong team, which included fewer than half of the players who’d been defeated by the Redmen, had been assembled. In 24 hours they were scheduled to leave for New York to catch RMS Queen Elizabeth for the journey to Europe. All but two of the 20 team members were members of the Royal Canadian Air Force, but they’d gotten there by various ways. Some were serving RCAF members, some were called up from the RCAF Reserve or had left the RCAF and were re-enrolled, a couple were ex-Army who were re-enrolled to wear Air Force blue and a few were even recruited and enrolled off the street. Civilian André Laperrière was given only 15 minutes to make up his mind about playing for the team, and the next day he was enrolled in the RCAF. Two former members of the Royal Canadian Navy were financially well-off and joined the team as civilian volunteers.

Many were veterans of the Second World War and two were highly decorated. Flying Officer Hubert Brooks held a Military Cross; he had escaped from a German prisoner of war camp and joined the Polish partisans, fighting with them for several months. Flying Officer Frank Dunster held the Distinguished Flying Cross for bringing a crippled Halifax bomber, and its crew, safely back to Allied territory. Leading Aircraftman Roy Forbes had also been shot down and evaded capture, making it back to Allied lines after five months, thanks to the help of the French resistance.

On the eve of departure, another disaster struck. The starting goalie couldn’t go for medical reasons so Squadron Leader Watson called an unknown amateur goalie: Murray Dowey. Within three hours, Dowey, who was ex-Army, had been granted leave from his civilian job and was on a train to Ottawa. A few hours later he was sworn into the RCAF and on the train to New York. No-one besides a couple of Flyers’ members who had played with him on civilian teams had ever seen him in action.

After putting up with terrible food and accommodations and playing some exhibition games in England and on the Continent, the Flyers made their way to St. Moritz. Flying Officer Brooks was selected to carry the Canadian flag for the entire Canadian Olympic team for the opening ceremonies on January 20.

There was a lot of national pride at stake for the unknown RCAF team. Canada had taken hockey gold in the Winter Olympics in 1920, 1924, 1928 and 1932. In 1936, the British had won the gold, but their ranks were stacked with Canadian or Canadian-raised players. The 1948 Games were the first winter games to be played since then – and the world was watching.

In a nutshell, the Flyers were unstoppable.

Later on January 20, the Flyers hit the ice for their first match against the Swedish team. But before play began, Sergeant Boucher, the team coach, had to make a difficult decision. Under Olympic rules, he could only dress 11 players, plus the spare goalie, leaving the others on the sidelines. He kept the same lineup throughout the games as it was a winning combination, but it was difficult for the players who’d fought so hard to get to St. Moritz, only to be left out of the action.

The Canadians beat the Swedes 3-1. By then, Leading Aircraftman Dowey had shown what a superb goalie he was. An accomplished baseball player, he had begun catching the puck when he was a teenager, fashioning a makeshift trapper glove out of a baseball catcher’s glove. During the Olympics, he amazed the spectators with his never-before-seen skills.

On day 3, the Canadians beat the defending gold-medal British team 3-0 in a blizzard that covered the outdoor arena in an inch of snow. Players shoveled the ice surface during the three-and-a-half-hour game that was also marred by bad refereeing.

February 2 was warm and sunny and the ice surface turned into a morass of slush and water. The Flyers beat the Poles, who had struggled to field a team, 15-0. The players felt it was unsporting to beat the Polish team so badly but Olympic scoring rules made every goal count in the final medals outcome.

The next day, the Flyers defeated the team from Italy – another nation struggling to recover from the ravages of the Second World War – 21-1. On February 4, warm weather again destroyed the ice surface, and the game against the U.S. team was postponed by a day. Many thought that this match would bring an end to the Flyers’ winning streak, but on February 5, the Canadians decisively beat the Americans 12-3.

Next up was the game against the Czechoslovakian team, which was coached by a Canadian. The Czechs were a tough team, and the game was hard-fought on both sides. In the end, however, the score was 0-0. Only two more games stood between the Canadians and the podium.

In game 7, the Canadians beat the Austrians 12-0, again playing through a snowstorm. Finally, the last day of the Olympics arrived, and the Flyers were up against the hometown favourites – the Swiss team.

Once again, the weather was uncooperative, but the Flyers “overcame handicaps of slushy ice and partisan refereeing,” according to Canadian Press reporter Jack Sullivan. “Ice conditions were so bad that at times the game threatened to develop into a farce,” he wrote. As the game drew to a close, Swiss fans even started throwing snowballs at the Canadian players!

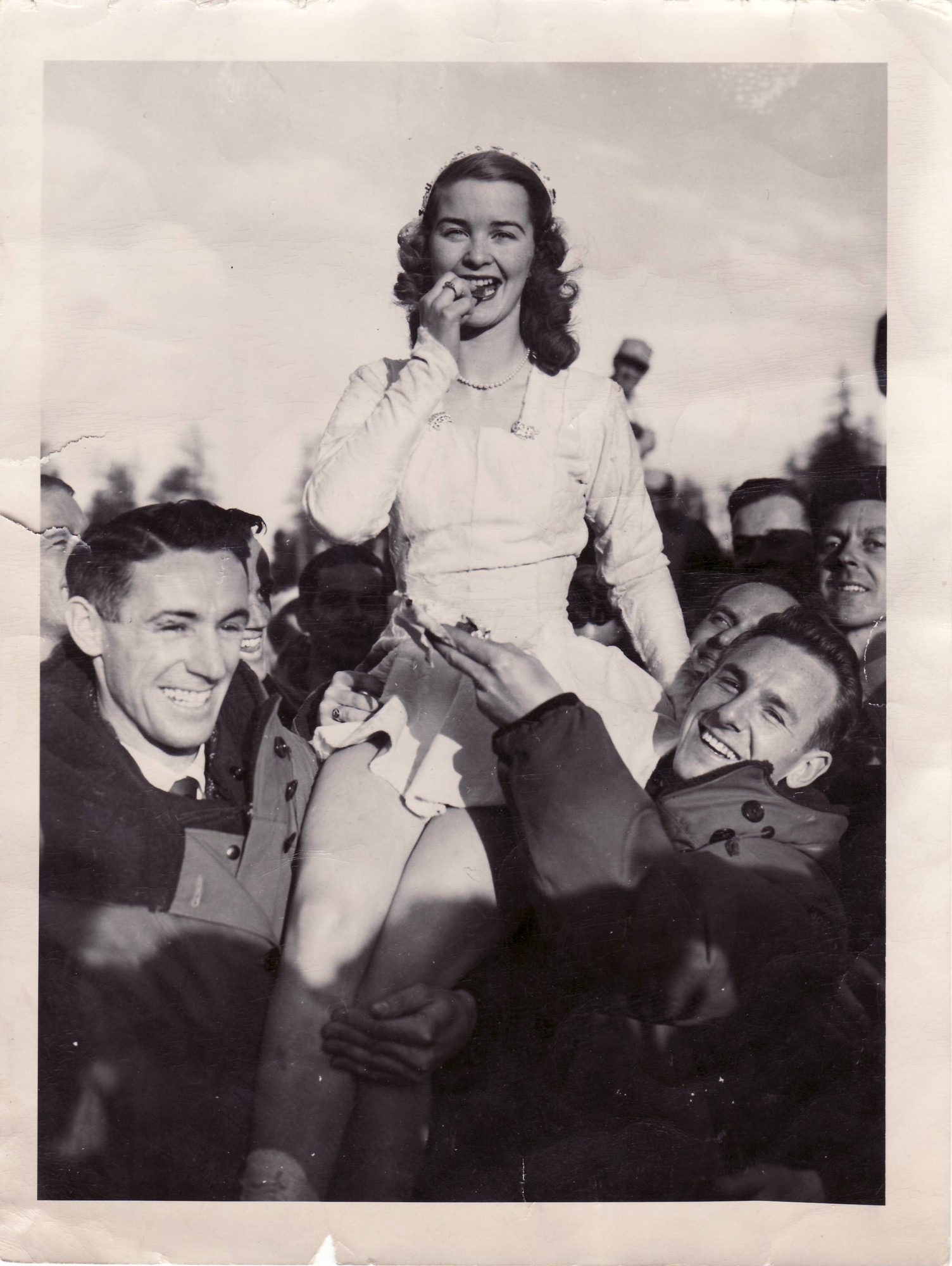

The Flyers persevered. They won the game 3-0, and took the gold medal. On top of that, goalie Murray Dowey had allowed only five goals over eight games, and had played five shut-outs. The Royal Canadian Air Force Flyers, who just two and a half months earlier had seemed like no-hopers, and figure skater Barbara Ann Scott, had won Canada’s first two Winter Olympic gold medals.

In a telegram sent to Squadron Leader Watson, Prime Minister William Lyon MacKenzie King said, “The victory of our team will be received with rejoicing throughout all parts of Canada . . . . heartiest congratulations on the team’s splendid achievement.” It was a far cry from newspaper headlines such as “Team proves inadequate for Olympic Games” that had followed their defeat by the McGill Redmen.

The next day, a celebration of a different sort took place as Flying Officer Brooks and Birthe “Bea” Grontved were married in St. Moritz. Barbara Ann Scott was the maid of honour and Squadron Leader Watson was the best man. Afterwards, most of the team members played several weeks of exhibition games in Europe, in part to help cover the costs of their participation. Eventually they made it home to Canada, where they were welcomed with a parade through the streets of Ottawa.

The Flyers faded back into obscurity after that. The team was officially disbanded on April 11, 1948, and many players returned to their civilian jobs. Others continued their careers with the RCAF, including Orval “Red” Gravelle, who had been a bellhop at the Chateau Laurier hotel in Ottawa before being convinced to join the RCAF and play for the Flyers.

In 1971, the Flyers were inducted into the Canadian Armed Forces Sports Hall of Fame and in 2008 they were inducted into the Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame.

- Squadron Leader Dr. Sandy Watson – Manager

- Sergeant Frank Boucher – Coach

- Corporal George McFaul – Trainer and equipment manager

- Flying Officer Hubert Brooks

- Leading Aircraftman Murray Dowey

- Flying Officer Frank Dunster

- Leading Aircraftman Roy Forbes

- Sergeant Andy Gilpin

- Aircraftman First Class Orval “Red” Gravelle

- Corporal Patsy Guzzo

- Mr. Wally Halder – highest scorer during the Olympic Games

- Aircraftman First Class Ted Hibberd

- Corporal Ross King

- Aircraftman Second Class André Laperrière

- Flight Sergeant Louis Lecompte

- Aircraftman First Class Pete Leichnitz

- Mr. George Mara – Team captain

- Leading Aircraftman Ab Renaud

- Flying Officer Reg Schroeter

- Corporal Irving Taylor

Gold Medal Misfits: How the unwanted Canadian hockey team scored Olympic glory, by Pat MacAdam, published in 2007 by Manor House Publishing

Against All Odds: The Untold Story of Canada’s Unlikely Hockey Heroes, by P.J. Naworynski, published 2017 by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

Chapters 8 and 9 of The Life and Times of Hubert Brooks, MC, DC at http://www.hubertbrooks.com/8_0HubertBrooks_RCAFflyer.html (accessed February 7, 2018).

Images of the pages of Andy Gilpin’s Olympic scrapbook can be viewed at http://fliphtml5.com/btaf/vrop (accessed February 7, 2018).

Page details

- Date modified: